A Search for Family, a Love for Horses and How It All Led to Kentucky Derby Glory

Herbie Reed has been fishing, and the catch was plentiful. The 75-year-old pulled in about 30 crappie from a nearby honey hole, a continuation of his family’s recent run of good fortune. It is late afternoon, and he has poured himself a Woodford Reserve on the rocks and sits down at his dining room table with his shirt unbuttoned to his belly, ready to explain how he arrived at this impossibly blissful moment in time.

“I came up by myself,” he starts.

Unwanted and uneducated, Herbert Ray Reed says he walked out of an Appalachian hollow as a child in the 1950s and never went back. His mother had died when he was 5 years old, and the family structure unraveled after that. Hitching a predawn ride on a cattle truck at 9 years old led him away from dark times in Pecks Creek Hollow in rural Powell County to this town of Versailles, where he showed up unannounced at his aunt’s house. “My God, honey,” he recalls her saying to him. “How did you get here?”

She was one of about a dozen people who took him in at varying points in a chaotic childhood. After settling in this bluegrass region of Kentucky, Herbie lied about his age to get a job riding racehorses. He was 14. He wasn’t a feral child, but in many ways Reed was raised by horses. They gave him an occupation, an outlet, an opportunity to be somebody. Horses became a generational family business—a source of revenue and pride and profound heartache, as well.

Eleven days ago, one horse raised the Reed name to the highest level of the equine game. Rich Strike, trained by Herbie’s son, Eric, won the Kentucky Derby in breathtaking fashion—with a spectacular late charge down the stretch to collar favored Epicenter before the wire at outrageous odds of 80–1. It was the second-biggest upset in the 148-year history of America’s oldest continuous sporting event.

Eric had Herbie join him at the post-race press conference, even though he had no direct involvement in training Rich Strike. Along with owner Rick Dawson and jockey Sonny Leon, they were such big-race novices that they had to be told to sit down for the interview. Then, Herbie and Eric informed the world about their bond, until there were tears shed in the room and from the podium.

“He’s been going to the track with me since he was 6 years old, and that’s no bull,” Herbie said that evening at Churchill Downs. “He would go every day, and when he was 8, he could put a spider bandage on a horse, and most people don’t even know what it is anymore.

“He said, ‘I know what I want to do. I’m not going to college; I’m going to train horses.’ And if you find something you love to do, you never work. He found something he loved to do, and he’s good at it, and I’m as proud as I can be of him.”

Why did young Eric Reed tag along with Herbie to the barns in the morning?

“It wasn’t so much the horses early on,” Eric says. “I idolized my dad. That’s why I did it.”

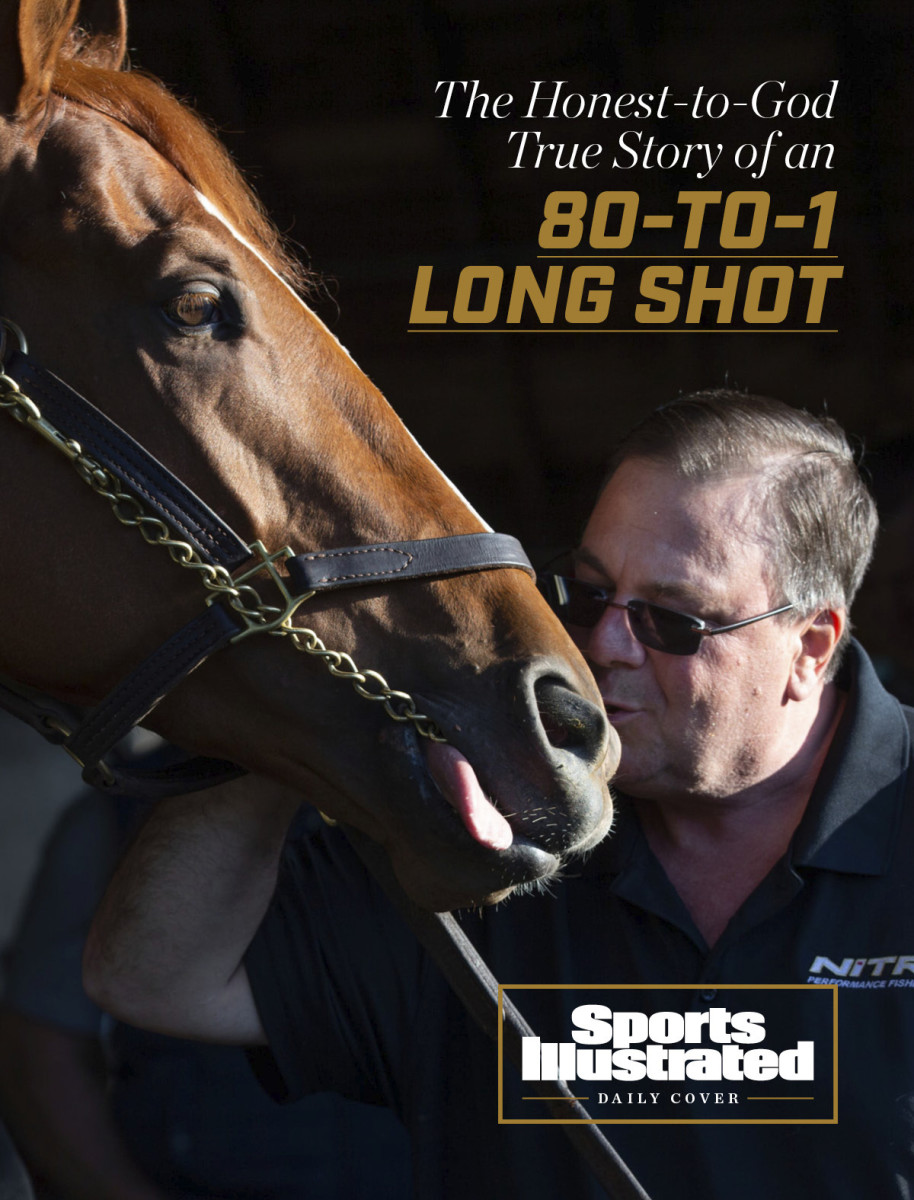

Less than 72 hours after that life-altering two minutes in Louisville, Rich Strike is in repose in his stall at Eric Reed’s Mercury Equine Center outside Lexington. The shedrow is quiet, and there is nothing to mark the presence of nascent racing royalty. When Reed approaches, “Ritchie” comes to the stall gate and cranes his neck out, softly trying to playfully bite his hand. The trainer laughs and dodges, patting the chestnut colt’s nose.

This is Reed’s 15 minutes of fame, but he happily steers a reporter toward his dad’s life story—“It could be a Hollywood movie,” he says. Right then and there, standing in the barn where Rich Strike resides, Eric answers a request to interview Herbie by suggesting an immediate road trip. He abruptly jumps in his Chevy Tahoe—with the rusted sideboard and three fishing rods in the back—and heads toward the exit of the farm. He apologetically brushes off a TV reporter waiting for him at the front gate and drives 40 minutes west to meet with Herbie.

Father and son share a large parcel of land off a narrow strip of blacktop outside Versailles, their houses just a few yards apart. One is something of a luxury log cabin. The other is more modern and serves as a part-time bed and breakfast (“Rabbit Creek”). The two men frequently fish and talk horses together, just as they have for decades.

“Everybody loved him,” Eric says of Herbie’s training days. “He was happy, and people would come to him all the time with questions: Herbie, help me, I can’t figure this horse out. It was like he was a guru or something. I remember all the admiration for him. I kept thinking, ‘Man, that’s what I want. I want people to think of me that way.’”

The horse racing world is split on how to think of Eric Reed today. Some are disappointed—even angry—that he made the rare and controversial decision not to race the Kentucky Derby winner this Saturday in the Preakness, the second leg of the Triple Crown. Others are lauding his resistance to public pressure, instead choosing what’s best for Rich Strike and what adheres to his own training philosophy.

Rich Strike isn’t at Pimlico Race Course but still looms as the dominant story line in Baltimore this week. He is the horse who shocked the world twice, first in victory and now in absentia. As such, it’s worth remembering where the Reeds came from—specifically, a place where the Triple Crown isn’t even a daydream, much less a consideration. A place where the gift of a big-time horse is to be protected like a Ming vase.

“You know, if you run the Preakness you’ve blown the Belmont,” Herbie says. “That looks like where [Rich Strike] wants to go; a mile and a half [the Belmont distance] is right up his alley. You hate to [skip the Preakness], but like Eric said, ‘I ain’t got but one good horse; I gotta take care of it.’ He’s got to do what’s best for the horse.”

That horseman mantra was handed down from father to son, and it’s why sharing that inconceivable Derby moment with Herbie was the true reward for Eric Reed. He made a lot of money and gained a lot of fame on the first Saturday in May, and felt some validation after working on the margins of the sport for so many years. But mostly Reed is leveraging this pinch-me moment to honor his father, a survivor who started a lineage of perseverance.

“You have to get lucky in life, and I’ve been lucky,” Herbie says, for the moment ignoring the unlucky episodes he’s also endured. “I stop and think sometimes, ‘What the hell made me do all this?’ I don’t know, but I had no fear in me.”

No fear led him to hitchhike around parts of Kentucky in search of something other than a home life he won’t discuss in detail. “I lived in some bad-ass places,” he says.

“At that time, I hated everybody. I’ll take some things to my grave, I guess, because there were people involved who aren’t here to defend themselves. But some bad things happened.”

No fear led to running away from whoever was caring for him multiple times, to skipping school, to giving up on education at an early age, to tattooing his initials into his forearm with a cluster of pins dipped in ink at age 12. “I’d give anything in the world if I hadn’t,” he says. “I hate ’em. It looks terrible.”

And no fear led him to thoroughbred racing, having seen a friend make up to $16 a day galloping horses. Fourteen-year-old Herbie Reed didn’t just lie about his age when he went to the barn of prominent Kentucky trainer Doug Davis. He lied to one of Davis’s assistants about his experience on horseback in asking for a job breaking yearlings. The fib became obvious to the assistant when Herbie got on the wrong side to mount the first horse they tried to put him on.

“He threw that saddle up and I’m standing on the wrong side,” Herbie recalls. “He said, ‘What are you doing? Boy, look, I know you’re having a hard time, but quit that damn lying. You ain’t 16 and you ain’t never been on no damn horse.’”

Still, they gave him a chance. Herbie climbed aboard four yearlings that day and showed an immediate instinct for the job. That led to becoming an exercise rider for Davis at Keeneland Race Course and subsequent riding jobs for other trainers and breeders. During that time, Davis and other horsemen would eat lunch at a diner in Versailles after the morning work was done. One day, a friend pointed out a pretty waitress who was sweeping around their table so often that “there’s going to be a hole in the damn floor.”

“I couldn’t ever remember anybody putting an arm around me and saying, ‘I love you’ … But once I got a family and saw how important it was, you realize.” —Herbie Reed

That’s how Herbie met Glenna, his wife since 1964. About nine months after they met, the couple decided to elope. Davis, the trainer, had been saving Herbie’s money for him to make sure he didn’t blow it. He delivered the boy $900 and a warning when he asked for it to get married. “I think you’re making a bad mistake,” Davis told him. Herbie bought a pink ’53 Ford for $50, and he and Glenna ran off to Tennessee to get hitched. He was 16, but once again fudged his age to get a marriage license. They came home and hid the news from Glenna’s family for a while.

Scott Miller, a local horseman who would become mayor of Versailles and gave Herbie a job at a young age, convinced him he had to tell Glenna’s father the truth. “Go out there and be honest with this man,” recalls Stiles Miller, Scott’s son. “Tell him what you did.”

Herbie did. After some immediate blowback, Glenna’s father eventually became a father figure to Herbie.

“Her daddy didn’t want nothing to do with me,” Herbie says. “He knew how I came up. I’ve got to thank her father for everything. I had that monkey on my back. When you come up like that, you just don’t know how to control yourself. Her dad would take me in and we’d talk. I’d get so mad I wanted to kill him. He used to tell me, ‘When you get so mad you want to hurt somebody, start counting backwards from 100 back. By the time you get to 50, you won’t want to do it no more.’”

Wiser but not richer, Herbie doubled down on his efforts to make money. He was galloping horses at Keeneland Race Course in the morning, then working nights at a Texaco near the couple’s apartment six days a week. He was getting by on five hours of sleep a night.

“When Glenna and I started out, we didn’t have a pot to pee in or one to pour it out of,” he says. “Me and her, we didn’t have s---.”

Baby Eric arrived soon thereafter. Meanwhile, Herbie’s horse savvy earned him moves up the ladder from exercise rider to assistant trainer for some prominent Kentucky conditioners before he eventually went out on his own. Equibase statistics show Herbie won 73 out of 707 races from 1976 to 2011, earning total purses of $670,328. Those are modest numbers. Herbie had some success at races on the Kentucky circuit, but resisted overtures from at least one well-heeled owner to take a string of horses to race in Florida for the winter. After the upbringing he had endured, the usual nomadic trainer life held no appeal.

“I didn’t know what a family was,” Herbie says. “When I got married, I couldn’t ever remember anybody putting an arm around me and saying, ‘I love you’ or encouraging me to do better. It just never happened. You know, you don’t miss what you never had. But once I got a family and saw how important it was, you realize.”

Soon enough, young Eric Reed was joining his father at the track. He would never leave it.

Nearing the end of his time at Lafayette High School in Lexington, Eric told Herbie that his career plans were set. They didn’t include college. Herbie didn’t like what he was hearing.

“I didn’t want him to do it,” Herbie says. “He was smart. He never did homework, made straight A’s, and I thought, ‘Why waste that? Go to college.’ The one thing I regret is that I don’t have an education. I made it to the ninth grade. I don’t care what anybody says, when you’re around educated people and you don’t have one, you feel inferior. Because you can’t talk on their level. One thing about college, it opens doors you can’t open any other way.

“But he told everybody, ‘I’m way ahead of anybody going to college because I know what I’m going to do. I’m going to train horses my whole life.’”

Eric began by assisting his dad, who offered no shortcuts or favors. One frigid winter night at Latonia Race Course in Northern Kentucky (now called Turfway Park), Herbie dispatched Eric to sit outside a horse’s stall for hours leading up to a race, offering him a blanket and nothing else.

Eventually, Eric started out on his own, navigating the same low-stakes claiming circuit his dad had worked. When he called home once from Ellis Park in Henderson, Ky., to ask his dad for advice, this was the response: “Look, brother, I can’t tell you nothing. You’re training those horses now.”

After plugging along at a modest clip for more than 15 years, Reed started to see an uptick in results in the early 2000s. More wins, more horses claimed, more purse money. The financial backing of a thoroughbred owner for whom he trained allowed him to take a big swing—buying a 60-acre property that would become Mercury Equine Center in 1985. The place had been part of fabled nearby Spendthrift Farm at one point, but had fallen into some disrepair. Reed and his wife, Kay, went to work refurbishing it.

With a ⅝-mile oval for training,160 stalls and plenty of paddock land, they built their dream farm. Within a few years, Reed was winning more races and purse money in a year than his father did in 35 years. He was a tier below the top trainers in the sport, but making a good living and enjoying his life.

Until the phone rang late one night in December 2016.

A thunderstorm had rolled through on an unseasonably warm winter night, and a lightning strike is believed to have ignited one of three horse barns on the property. What ensued was a nightmare. Jumping in the car and rushing from Versailles to the farm, Eric says he could see the glow of the fire painted against the dark sky from more than a mile away.

“It was raining sideways, pouring rain,” Reed recalls. “I told my wife, ‘We’ve lost everything.’”

It turned out not to be the case—by chance of fate, the wind from the storm was blowing the opposite direction from the way it usually blows on the farm, away from the other two barns and the house on the property. But the losses were still horrific: 23 horses died, 13 escaped.

The memories are stark and searing: one of his workers, “absolutely naked, no shoes, no underwear, running in and out and pulling horses out”; some horses exiting the barn with their ears or manes on fire; workers having to hold back Kay to keep her from running into the blaze. The fire was put out a couple of hours later and the temperature plunged in the aftermath of the storm. Reed told his staff to go home and return at first light to survey the damage and retrieve the horses that had been let loose.

“We got back here at about 7,” Reed says. “I thought the night was horrible, but then you see the bodies. … I’m telling you, man, nobody deserves to see that. That’s when the worst of it hit me.”

Gutted, Reed and his attorney began the process of calling the horses’ owners to tell them which animals had survived and which had perished. He thought strongly about quitting the business. The voice he needed to hear most was his father’s.

“About three days into it, my dad calls me,” Eric recalls. Hey boy, you still on your feet? You got to get back to training them horses, Eric. People are paying you, and those horses need to get out of the barn. Can’t nobody tell you what to do, but I am going to throw one thing at you: If you quit, them horses died for nothing.

Gradually, Reed pulled himself and his operation back together. He dabbled in a YouTube hunting and fishing show with a couple of friends, The Bluegrass Boys Outdoor Show. But his heart was in training horses, and with the help of friends and family he persevered.

One thing Reed did upon rebuilding the burned-down barn: He left a clearing, surrounded by white split-rail fencing, where part of the carnage had occurred. No one sets foot in there, other than to mow the grass. “This is hallowed ground,” he says. “This ground, we know what happened here and it’s not going to be forgotten.”

Reed was also not forgotten by his clients and others in the industry. In a business where relationships often fracture and owner second-guessing is rampant, Reed maintained good rapport with those who pay the bills. That includes St. Louis businessman Mike Schlobohm, who sent Reed the filly Resurrection Road in 2018 largely because his training fees were affordable for an entry-level owner. Five years later, Resurrection Road has won five of 21 starts and earned nearly $125,000 in purse money for a satisfied owner.

“He just always has been super good to us,” Schlobohm says. “He always wants to do what’s right for the horse. He treats every horse individually, he finds the right spots for them to race, and his horsemanship eliminates a lot of vet bills.”

(Knowing what he did about how Reed operates, Schlobohm said last week, “I guarantee he does not want to run that horse in the Preakness.” The next day, Rich Strike was scratched from the race.)

Reed’s business continued chugging along at a steady but unspectacular pace when he hooked up with Dawson in 2021. An oil and gas guy from Edmond, Okla., Dawson was reentering horse racing after some unspecified bad experiences that Dawson elected not to discuss. Dawson is a small player, having sent three horses to Reed before the two claimed Rich Strike for the paltry sum of $30,000 as a 2-year-old last September. The pair won a five-way “shake” for Rich Strike after he won his second career race by 17 lengths at Churchill Downs. Exciting as that was, it’s hardly a gateway to the Kentucky Derby.

Reed took Rich Strike back to Mercury Equine Center and began prepping him for a race at Keeneland three weeks later. Reed watches his horses’ morning gallops from what is essentially a combination clocker’s stand and office on the turn of his home training oval, a place where he keeps cans of Raid handy to fend off the omnipresent wasps. “With this, I’m Clint Eastwood,” he said, holding a can of the pesticide. “Without it, I’m scared of ’em.”

Coming off that big maiden score at Churchill, Rich Strike was sent off at 4–1 in the race at Keeneland on Oct. 9, but finished a dull third in an $80,000 race. It dampened some of the excitement in the group, but it did not change Reed’s plan.

“I don’t know another trainer in the world that would have run that horse back at a stake after that race at Keeneland,” Herbert says. “I wouldn’t have seen that kind of talent in that horse. He knew he had something. After Keeneland he said, ‘I’m going to tell you, he’s the best horse I’ve ever trained.’”

Eric knew Rich Strike had a troubled trip at Keeneland and figured a little more racing luck would reveal the colt’s talent. But the day after Christmas, he finished fifth at 46–1 odds in a stakes race at the Fair Grounds in New Orleans—14 ½ lengths behind Epicenter. “That would have been the end for me,” Herbie says. “I would have run him for $50,000.”

Still undeterred, Eric pointed Rich Strike toward Kentucky Derby prep races in 2022 at Turfway Park, more familiar territory for Reed and Leon. The horse performed better there, finishing third twice and fourth once in stakes company, earning enough Derby qualifying points to reach the fringe of making the race. Winning was another matter entirely. Since that maiden victory in September, Rich Strike had never led another race.

Rich Strike came to Churchill Downs in late April as a complete afterthought. He had one timed workout at the track, on April 27, and no one cared. It seemed unlikely he would get in the race. He was “in it for the saddle cloth,” as the saying goes, referring to the yellow fabric memento Derby horses wear with their name on it beneath their saddles when they go to the track to train in the morning.

What happened the day before the Derby became part of the instant Rich Strike lore. Seemingly shut out of the 20-horse field, a last-minute scratch cleared the way for him to enter. While the horse’s connections were ecstatic, the outside world yawned. No one gave the horse a chance, and he was sent off at the longest odds in the field.

Eric and Herbert Reed watched the race on the big screen in the Churchill paddock. Taking note of the race leaders blazing through the first quarter mile—the fastest in Derby history at 21.78 seconds—Herbert said to his son, “We might not win it, but I know they won’t.” The half-mile split was less than 46 seconds, still a withering pace that set up the race for a dead closer—Rich Strike’s wheelhouse.

When Derby rookie jockey Leon—himself as big a long shot as the rest of the crew—made a series of bold moves and smart decisions, he put Rich Strike in position for a dash to the finish. When he caught Epicenter and Zandon in the final sixteenth of a mile, almost no one in the crowd of 147,000 knew the horse suddenly stealing the Kentucky Derby on the rail. But the boys watching in the paddock knew, disbelief and euphoria commingling. When Rich Strike crossed under the wire first, Eric Reed collapsed to the ground—a bad back, a rush of emotion, overwhelming shock, whatever the reason. Herbert feared his son was having a heart attack.

“Scared the hell out of me,” Herbert says. “Then he got up from there and I started laughing at him.”

As the ecstatically unruly group howled and hugged and staggered its way toward the Kentucky Derby winner’s circle, Eric Reed’s first thought was who he wanted next to him for this walk of a lifetime. He called out, “Where’s my dad?”

Herbert Reed was right there behind his son. As he has been across every step of an incredible familial journey.

Read more of SI’s Daily Cover stories:

• The Return and Rebirth of the WNBA’s AD

• Does the NBA Have a $@&!*% Problem?

• Sicilian Scrum: One Italian Rugby Club is Standing Up to the Mafia