The Wild Life of the Last Black Jockey to Rule the Kentucky Derby

Kendrick Carmouche grew up the son of a jockey deep in Cajun country, in south Louisiana, where kids climbed on racehorses at an early age to find out whether they had what it takes to be a rider.

His first time on a fast horse, Kendrick was about 8 years old. His father, Sylvester, tied a rope around Kendrick’s thighs and around the horse’s underbelly to keep the kid onboard. It worked … kind of.

“That horse took off on me,” Carmouche says with a laugh. “I was underneath him by the time he stopped. That will make you grow some balls.”

Kendrick Carmouche grew into a successful jockey—more successful than Sylvester, who earned an infamous niche in horse racing history. In a profession dominated by white and Latin jockeys, he’s become the most prominent Black rider in America. Carmouche got his first Kentucky Derby mount in 2021 after winning the Wood Memorial at 72–1 odds aboard Bourbonic, and he’s now a major player on the New York circuit.

With that distinction comes responsibility. He is picking up a lost legacy, reconnecting the sport to a time more than a century ago, when Black jockeys ruled. Now they’ve all but disappeared.

“I have to embrace it and speak about it when people ask me,” the 39-year-old Carmouche says. “This is an open sport for anybody, if you have the faith and confidence in yourself to do it. That’s what I want to put out there, for Black jockeys and anybody else who wants to get into horse racing.”

On his way up the racing ladder, Carmouche won the Jimmy Winkfield Stakes at Aqueduct Racetrack in New York in 2018. It was a profound symbolic confluence, a rare Black jockey winning a race named after a Hall of Fame Black jockey—one whose life story might be the wildest in the history of the sport.

Carmouche said he got to meet a relative of Winkfield after winning the race but admitted he doesn’t know much of that life story. Here is the history lesson, as Carmouche tries to become the first Black jockey to win the Kentucky Derby since Winkfield last did it, in 1902. Shortly thereafter, American thoroughbred racing turned its back on Jimmy Winkfield and everyone who looked like him.

The first Kentucky Derby was contested just a decade after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, ending the Civil War. The winning horse was Aristides, the winning trainer was Ansel Williamson, and the winning jockey was Oliver Lewis. Both the trainer and jockey were Black.

One of the United States’ earliest sports was flush with Black achievers in the 1800s. In the South, many of them were slaves who had been entrusted with caring for the thoroughbreds their masters owned. They developed the skills needed to become successful riders, and after the war, many freed slaves became jockeys across the nation.

Thirteen of the 15 riders in that first Kentucky Derby were Black. Of the first 28 Derby winners, 15 were ridden by Black jockeys. As the sport—and the Derby—gained popularity in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Black jockeys became stars.

Isaac Murphy captured three Derbies from 1884 to 1891, winning races at an unprecedented rate. And then along came Jimmy Winkfield.

George and Victoria Winkfield’s 17th child was born in a sharecropper’s shack in Chilesburg, Ky., just outside of Lexington. The little place was so crowded that the older children often slept on the porch, according to a 2002 profile of Winkfield in The Courier-Journal of Louisville.

A tiny child with unusually large hands, Winkfield gravitated toward horses and started riding bareback at age 7. He became a stable boy at Latonia Race Course in northern Kentucky at 15, earning $8 a month plus board. “I was rich,” Winkfield told Sports Illustrated in a 1961 story.

A year later he began riding professionally, getting his start in Chicago. By then, with racism on the rise in the U.S. and the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson ruling in 1896 upholding a “separate but equal” doctrine that empowered discrimination, Blacks were beginning to encounter difficulty making a living at the racetrack.

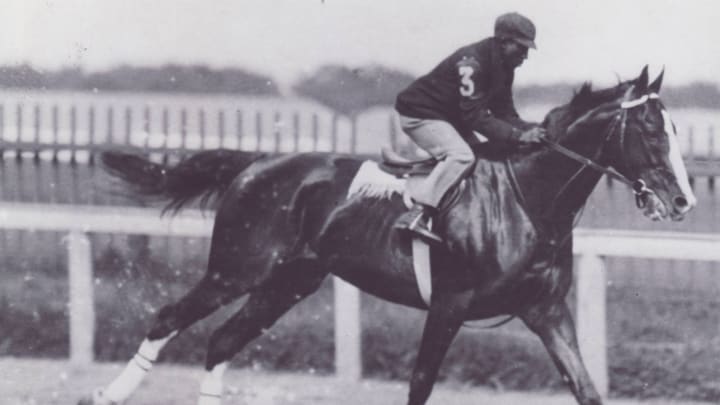

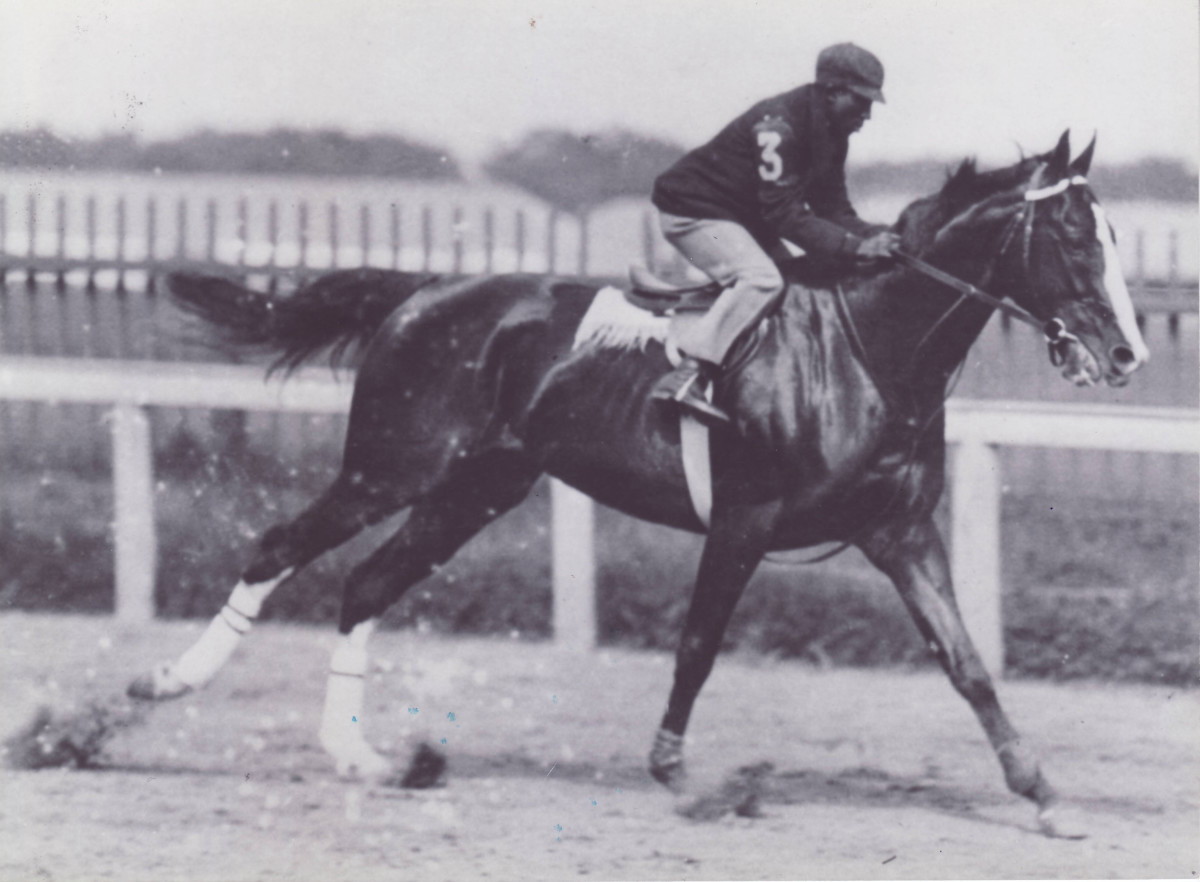

But Winkfield was an undeniable talent, light and calm and sure on a horse’s back. “He was a natural from the start,” Colonel Phil Chinn, a horse trader who saw Winkfield ride, told SI. “He just sat up there like a piece of gold.”

After a strong spring meet at the Fair Grounds in New Orleans in 1900, 18-year-old Winkfield finished third in his first Kentucky Derby aboard a horse named Thrive. He then came back to win the race back-to-back in ’01 (aboard His Eminence) and ’02 (aboard Alan-A-Dale). To this day, only six jockeys have ever won consecutive Derbies. But Winkfield’s success went well beyond those races; he was a routine winner throughout the calendar year. Bettors placed wagers on his horses simply because he was riding them.

The Courier-Journal has been the paper of record for Derby coverage for the entirety of the race’s 148-year history. The coverage of Winkfield after each of his Derby victories lauded his riding skills while always making note of his ethnicity, as Black jockeys became more rare.

In 1901: “[A] little chocolate colored negro whose home is in Lexington.”

In 1902: “[A]s black as an ace of spades, and a jockey whose last two years of riding has won him money and reputation.” The paper that day hinted at Winkfield’s heroic status among Blacks, noting that as the jockey went through the paddock area on the way back to the jocks’ dressing room after the Derby, “he was followed by fifty or sixty colored stable boys. They were patting him on the back and fairly carrying him through the crowd.”

The 1903 Derby coverage was both more humanizing and more crass. Winkfield lost that day aboard the favorite, Early, giving the horse what was by all accounts a bad ride. That includes Winkfield’s own reckoning. With a more judicious pace, he might stand alone in history as the only winner of three straight Derbies.

“I made my run too soon,” Winkfield was quoted as saying, with tears in his eyes and voice cracking. “I wanted to win this Derby more than any of the others. I wanted to win for the boss, and had I followed his instructions I would have won.”

Instead, after pushing Early too early, Winkfield was passed in the stretch by upset winner Judge Himes. It’s noteworthy that while The Courier-Journal routinely specified Winkfield’s ethnicity in its articles, using words like “colored” and “negro,” it quoted others saying worse about the jockey or to him.

Judge Himes’s jockey, Harold Booker, described Winkfield with a racist epithet. “I passed Early,” Booker said. “‘I have got that [n-word] beat,’ I said to myself, and then I went to the [whip], and Winkfield could not catch me.”

The Courier-Journal also quoted the race starter using the same word directly to Winkfield, after he prematurely turned Early toward the starting line. (There was no starting gate in use at the time.) “You little [n-word],” starter Jake Holtman reportedly said to Winkfield. “Who told you that you knew how to ride? You are not down at New Orleans now, so come on and get in line.”

That 1903 race was the last the Kentucky Derby saw of Jimmy Winkfield. The Louisville Herald noted on the day of the race, “The colored jockey is passing out and but a few representatives are left.” Historians say there were no Black jockeys in the Derby between 1921 and 2000.

White racists were gaining greater power at the turn of the 20th century as the Jim Crow Era took hold. Black opportunities were imperiled in many walks of life. A letter from lumber magnate John H. Kirby in The Courier-Journal on May 4, 1903, two days after Winkfield lost his last Derby run, expressed some of the ugliness of the times. “The Negro, left to himself, has little desire to figure in the more complex conditions of life—happy, at times indolent, shiftless, relying more on his white employer than upon his own efforts.”

With that as an antagonistic backdrop, Winkfield made a bad decision that signaled the beginning of the end of his American riding career. He reneged on a commitment to ride The Minute Man in a big New York race for prominent owner John E. Madden, who had the sprawling Hamburg Place horse farm in Lexington. Winkfield opted instead for a $3,000 payment to ride High Ball in the same race.

Neither horse won, and Madden reportedly vowed to exact revenge on Winkfield for backing out on him. There are conflicting stories about the fallout from that, with some saying Winkfield was effectively blackballed in U.S. racing and Winkfield himself telling The Courier-Journal that when he lost the mount on High Ball for that horse’s next race, he got mad and left the country.

The rest of Jimmy Winkfield’s life played out like a novel, veering between hardship and luxury and exotic travel.

At some point before departing the U.S., Winkfield went to Chicago for reasons that have been lost to the mists of time. While there, according to The Courier-Journal, he got involved in a dice game and drank tainted alcohol. The alcohol poisoning left him with crossed eyes that were noticeable in all subsequent photographs.

But that did not detract from Winkfield’s horsemanship, and his renown in that area led him all the way to Russia. He was a star rider there, living in luxury at a posh Moscow hotel and a country cottage, eating caviar for breakfast, riding horses for European royalty and business magnates.

The Russian Revolution changed all that. With Bolsheviks overthrowing the government and targeting the wealthy, Winkfield fled Odessa in 1919 with other horsemen and about 200 expensive thoroughbreds. “This ain’t no longer a fit place for a small colored man from Chilesburg, Kentucky to be,” Winkfield told SI in ’61.

The escape was an arduous journey to Warsaw, Poland, lasting at least two months and covering about 1,000 miles, including traversing the Transylvanian Alps. At times the situation was so dire that some of the horses were killed for food.

Encountering severe conditions in Poland, Winkfield yearned to keep moving. A Russian oil tycoon who was involved in horse racing had relocated to France and sent for Winkfield to join him there.

Reestablished at the racetrack, Winkfield resumed acquaintances with the daughter of a Russian aristocrat he had met years before, Lydie de Minkwitz. The two were married in 1921 and moved into an opulent chateau in Maisons-Laffitte. Winkfield won big races all over Europe, built a stable for 29 horses and fathered two children, living a comfortable life as an American expatriate.

Winkfield kept riding until 1930, retiring in his late 40s with more than 2,600 victories. He had won thousands of races to that point, and he began training horses and teaching aspiring jockeys the trade. Everything was fine until Hitler started beating the drums for what would be World War II in ’39. Winkfield sent his wife and daughter, Liliane, to Cincinnati to live with a relative.

He and his son, Robert, stayed behind to oversee their stable. When the Germans invaded France, Winkfield garrisoned French troops on his property, but eventually the Nazis occupied the country and took over his stable. In early 1941, he and Robert left France for America—a full-circle return for Winkfield to his humble roots.

A man who was one of the most accomplished jockeys in the world and then a successful trainer in Europe was reduced to stablehand work, galloping horses and mucking horse stalls along the East Coast. He went to work for Pete Bostwick in Aiken, S.C., and Bostwick remembered the name.

“You aren’t by chance the Winkfield who won the Kentucky Derby, are you?” Bostwick asked, according to SI. Winkfield affirmed that he was, and Bostwick asked, “Where have you been all these years?”

“Well I tell you, Mr. Bostwick,” Winkfield answered. “I been around.”

In the early 1950s, Jimmy Winkfield, his wife and his son returned to France and reassembled his training operation. He no longer won at the prestigious level he’d enjoyed before the war, but it was a competitive outfit. But in winter 1960, he came back to the United States for an operation that he thought might kill him—and if he were going to die, he wanted to do it in Kentucky.

Winkfield lived, and stayed with his daughter and her family for a while in Cincinnati. That spring of 1961, at the age of 79, he decided to attend the Kentucky Derby. It would be the last one he attended before his death in France in ’74.

In the days leading up to the race, Winkfield was invited as a guest of Sports Illustrated to attend the National Turf Writers Association dinner at the Brown Hotel in downtown Louisville. Winkfield arrived with his daughter, and they were denied entry. After 30 minutes of explanations and harangues, they were finally admitted.

The jockey was similarly delayed in entering the National Racing Museum and Hall of Fame. It wasn’t until after a few retrospective pieces were published in 2002, 100 years after his last Derby win, that the sport took a renewed interest in vanished exploits of Jimmy Winkfield. He finally was inducted in ’04.

Kendrick Carmouche is laid up for a few weeks in New York, recovering from a fractured tibia. He’s anxious to get back in the saddle, because this is an important stretch in the racing calendar. Kentucky Derby prep races are underway across the nation, pointing toward the big race on the first Saturday in May, and the jockeys are jockeying for rides aboard the most promising 3-year-olds.

After hearing a bit more about Winkfield from a reporter, Carmouche had a request: Can you send along some stories about him? It will help pass the time while he’s on the mend.

There is much to know about the wild life and times of Jimmy Winkfield, as the man who currently is America’s best Black jockey tries to reconnect thoroughbred racing with its more diverse past.