How Athletes Are Turning Arena Entrances into Fashion Shows

This story appears in the July 29–August 5, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated, which features the 2019 Fashionable 50 list, honoring the most stylish athletes in sports right now. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

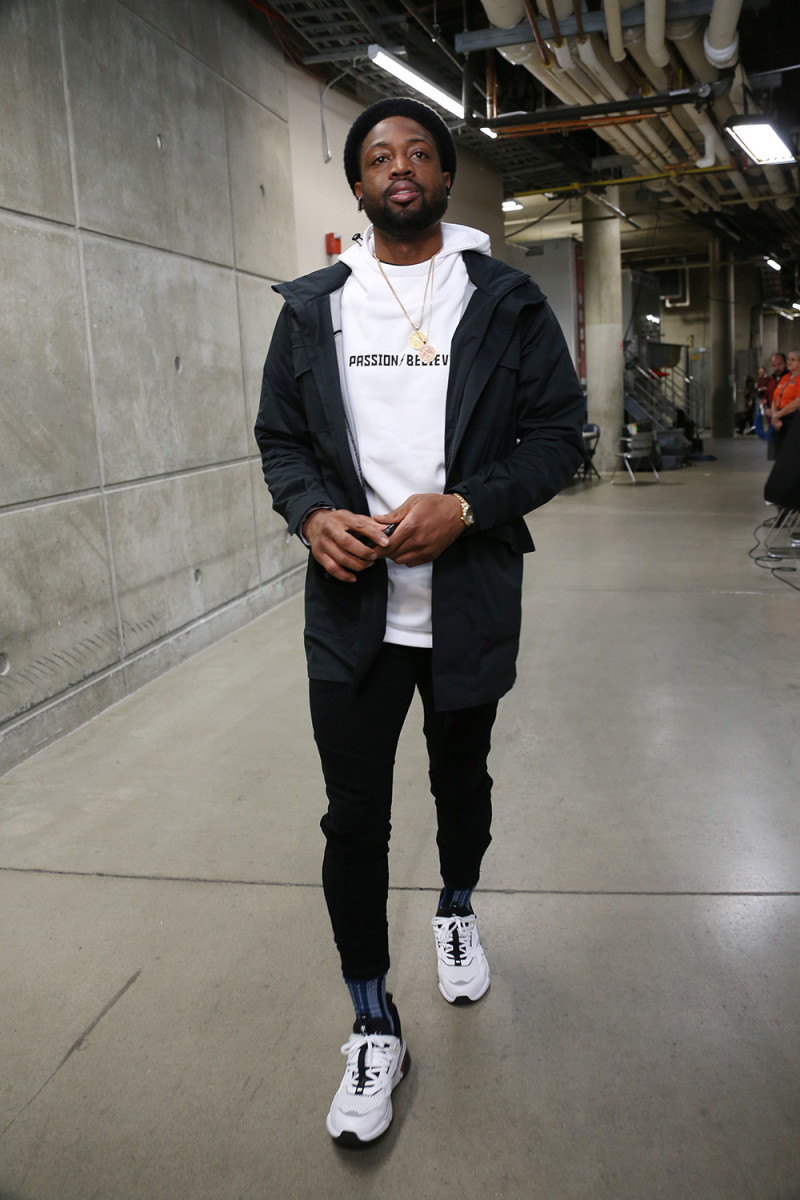

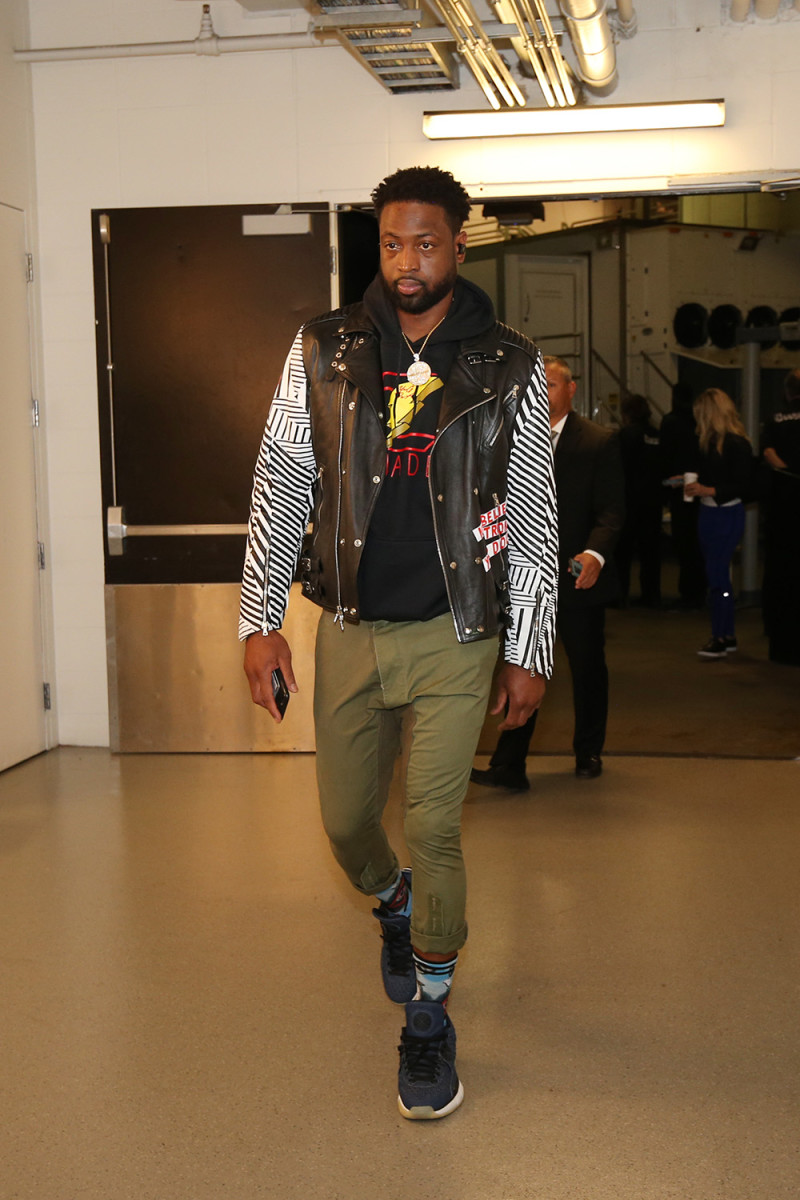

Dwyane Wade recognized the rituals of a fashion revolution as his teammates prepared to get off the bus before every Heat road game. The pat down of the skinny jeans. The smoothing of the blazer sleeves. The quick below-the-knee inspection to ensure that sneakers are tied, trouser cuffs break just right so those snazzy socks are visible . . . every Miami player seemed to have a checklist. “They might act like they don’t care,” says Wade, who retired in April after his 16th NBA season. “But when they get off the bus, they’re fixing their clothes because they’re about to hit that runway.”

The runway. The tunnel entrance. The arrival shot. Popularized by NBA stars such as Wade, LeBron James, Russell Westbrook and James Harden, the arena walk-in is now a staple of live broadcasts across all pro sports leagues—not to mention constant fodder for social media sartorialists from Miami to Milan. You know the scene: Dapper athletes strut through a cavernous hallway, headphones on and eyes up en route to the locker room as camera flashes flicker and news crews hustle to keep pace.

Granted, the stage often lends itself less to haute couture than hot garbage. “We’re trying to dress our asses off, and there’s 10 trash cans behind you when they take the picture,” Wizards guard Bradley Beal laments. Consider iconic Madison Square Garden, where visiting NBA and NHL players must summit a five-story, circular truck ramp from the security gate along West 33rd Street. “You’re winded by the time you get to the top,” Wade says. “Might be some things running past you on the ground, too.”

But the concrete catwalk has become more than just a platform for athletes to express their individuality before changing into their work uniforms. It connects them to existing fans, engages new ones, attracts sponsors and even helps send messages of social good. “It’s the closest thing to being in a fashion show,” says quarterback Tyrod Taylor, among the NFL’s sharpest dressers. “If you want to show your sense of style, the opportunity is pregame.”

Precompetition peacocking is hardly new. Centuries before Wade and his peers transformed the NBA tunnel, Roman gladiators paraded around the Colosseum pit flaunting purple-and-gold cloaks—or, as with second-century emperor Commodus, a lion’s pelt—before trying to slaughter one another. Says stylist Rachel Johnson, “There’s always some kind of entrance that a warrior makes before he goes into battle. And it’s the same thing with the guys today.”

Johnson and a handful of other full-time athlete stylists make a career out of curating those entrances. In the early 2000s, Johnson, then a recent Florida A&M graduate who majored in English education, was helping outfit rap stars such as Jay-Z and P. Diddy when she met then Bulls swingman Jalen Rose, who introduced her to the world of NBA couture . . . or, rather, whatever passed for it. “Jalen allowed me to understand how players ended up with pea-green suits with seven buttons and crazy collars,” the 45-year-old Johnson says. “The first time I went into his closet, I was like, What is this?”

It wasn’t that pro athletes had no sense of style. From the mink coats of Joe Namath and Walt Frazier to Allen Iverson’s baggy retro jerseys, pregame fashion was always a surefire way to attract attention. But then in October 2005, NBA commissioner David Stern enacted a “casual business attire” dress code for games, outlawing chains, do-rags and other hallmarks of Iverson’s street swag. “Everyone wants to be themselves and not feel like you have to fit in to a certain person’s view of how you should dress,” Wade says. “Even though now, if you look, [the outfits are] wilder than [they were] then.”

That same season Johnson began working with James, whom she met through Jay-Z. Then 20, LeBron rightfully saw the marketing potential in wearing luxury brands tailored to his 6' 8" frame. “That hadn’t been done before,” Johnson says. “Maybe they were getting suits from Armani or carrying Louis Vuitton luggage, but NBA players weren’t wearing special-made.” Above all, though, James had one mandate. “More than the latest trend,” Johnson says, “it was about being confident before he hit the hardwood.”

That is the basic goal for every sports stylist, but the process is more complicated. Take Dex Robinson, who dresses a dozen athletes, including wide receiver Marquise Goodwin, sack machine Khalil Mack and Taylor, the Chargers’ backup quarterback. With his NFL clients, Robinson begins planning for the up-coming season during OTAs in June, curating potential looks based on a variety of factors. Is it a prime-time game? Who’s the opponent? What would the weather likely be?

Robinson then visits each player before the start of preseason, armed with dozens of shirts, pants and shoes. “Typically, three to four 70-pound bags,” he says. “Gotta keep in mind, these guys are huge.” Finally, Robinson returns for a follow-up fitting during the regular season, and once more if a playoff berth looks possible. “I feel like a coach,” Robinson says. “I’m teaching them. I’m not just playing dress-up.”

Of course, not every player needs help. Westbrook and Suns swingman Kelly Oubre Jr. have cultivated two of the NBA’s boldest wardrobes by shopping for themselves. The same goes for Panthers quarter-back/feathered-bowler connoisseur Cam Newton and Saints defensive end Cameron Jordan, two of the NFL’s most fearless fashion plates. “When I rock heat,” says Jordan, “you know the effort I took to find it.”

As the son of tight end Steve Jordan, who spent 13 seasons with the Vikings in the 1980s and ’90s, Cameron grew up admiring players who wore “chinchilla and gator boots and big furs” for their pregame attire. Now Jordan’s heat—or “drip,” as stylish outfits are described—features T-shirts of superheroes (Green Lantern, Static Shock) and super-villains (Bane, the Joker), as well as a series of ’80s-inspired FUBU windbreakers and Reebok pumps.

“My kids are going to look back and be like, ‘Yo, daddy was swaggy in the day,’ ” Jordan says.

On June 3, a few hours before Game 4 of the Stanley Cup finals between the Blues and the Bruins, studio producer Mark Bellotti was standing near a bank of TV trucks parked inside St. Louis’s Enterprise Center. When he joined NBCSN in 2010–11, it hardly mattered to NHL broadcast crews when players arrived. “We cared in the sense that we might have a pregame interview scheduled,” Bellotti says, “but never found any other reason to cover that.”

Now? When Boston’s team bus backed into the loading dock at 4:15 p.m., five TV cameras and two still photographers scuttled into position, near a bank of portable toilets and a sign that read: hazardous material. Lenses trained on the door, they followed Bruins captain Zdeno Chara (dark suit, purple tie), center Patrice Bergeron (ditto) and winger Brad Marchand (navy, windowpane-patterned three-piece ensemble) as the team entered the building. Asked how he’d react if his crew missed out on these shots, Bellotti admits, “I would feel like a little panicked. It has become that much a part of the show.”

This obsession with pregame walks actually originated with postgame press conferences. The shift, at least according to NBA players and stylists, came during the 2012 playoffs, when Westbrook went viral answering questions in red, lens-less glasses and a short-sleeve Lacoste polo printed with big, colorful fishing lures. “We didn’t really start seeing the tunnel look until the past couple of years,” says stylist Megan Wilson, a former sports-fashion blogger whose clients include Pistons big man Andre Drummond. “The podium game came first.”

Perhaps the best reflection of the increased buzz can be found at a home office just 10 express stops north of Madison Square Garden. Each night during the NBA season, Jamaal Rich analyzes and reposts arrival shots from team photographers on his sports-fashion blog, More Than Stats. The site’s accompanying Instagram account boasts more than 55,000 followers; a similar page titled League Fits, a Slam magazine subsidiary, has nearly 300,000 followers. “Looks create conversation,” Rich, 31, says. “Fans are well-engaged in player fashion today. Either they’re critiquing the athlete’s style, or they’re inspired to dress different.”

NHL defenseman P.K. Subban recalls the endless flak he got for a “glistening burgundy sharkskin suit with a cougar-patterned inside lining” as a Canadiens rookie in 2011–12. “Now I’m seeing guys walk into games with hats on and checkered suits,” he says. “It’s another way to show personalities without hearing them speak.”

Like a picture, an outfit is often worth a thousand words. It can hint at team unity, like when Beal suggested that the Wizards wear all-black suits to a mid-January 2017 tilt against the Celtics—“Because it was a funeral game,” he explains—or when LeBron purchased gray Thom Browne suits for the entire Cavs roster in the ’17–18 postseason.

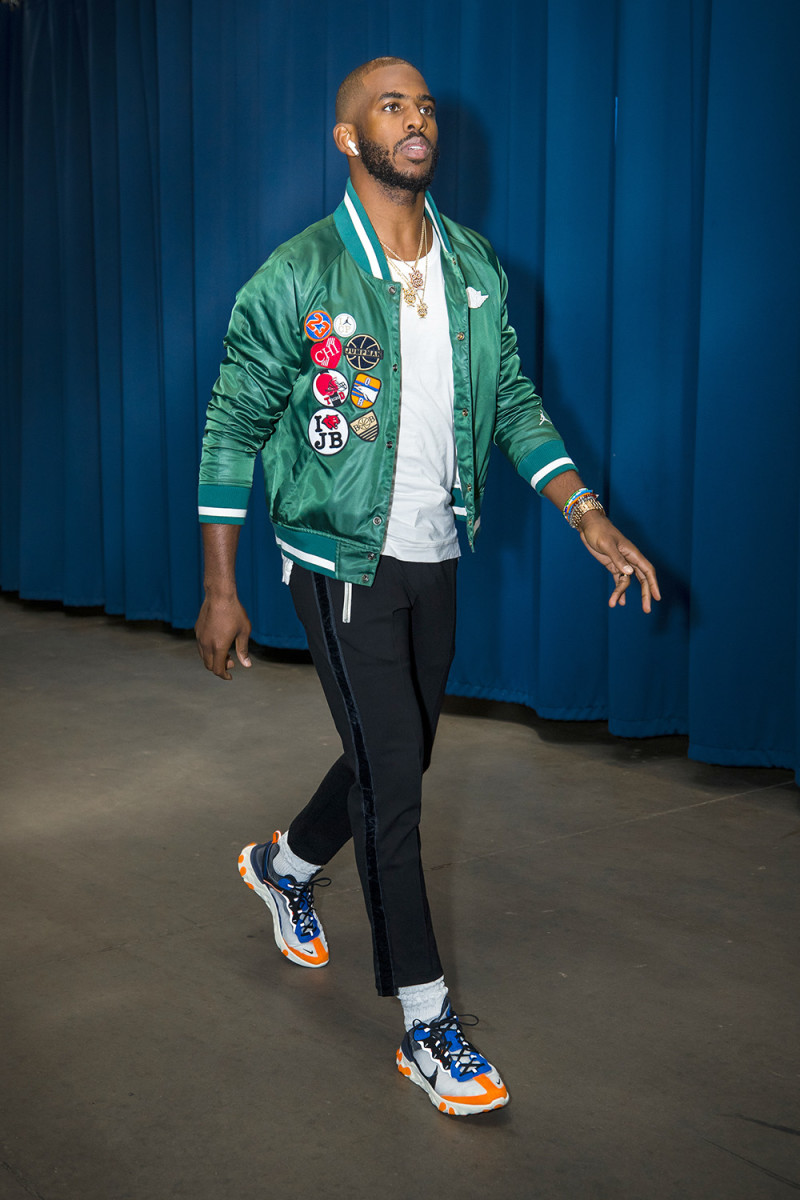

Other messages are much more personal. Before Game 4 of the 2019 NBA Finals, Raptors guard Jeremy Lin arrived in T-shirt adorned with a quote credited to actress Sandra Oh: it’s an honor just to be asian. And every single ensemble worn by Rockets point guard Chris Paul in the ’18–19 regular season and playoffs featured at least one item from an African-American designer. “This is an opportunity to use style as a vehicle for a social message,” says Paul’s stylist, Courtney Mays.

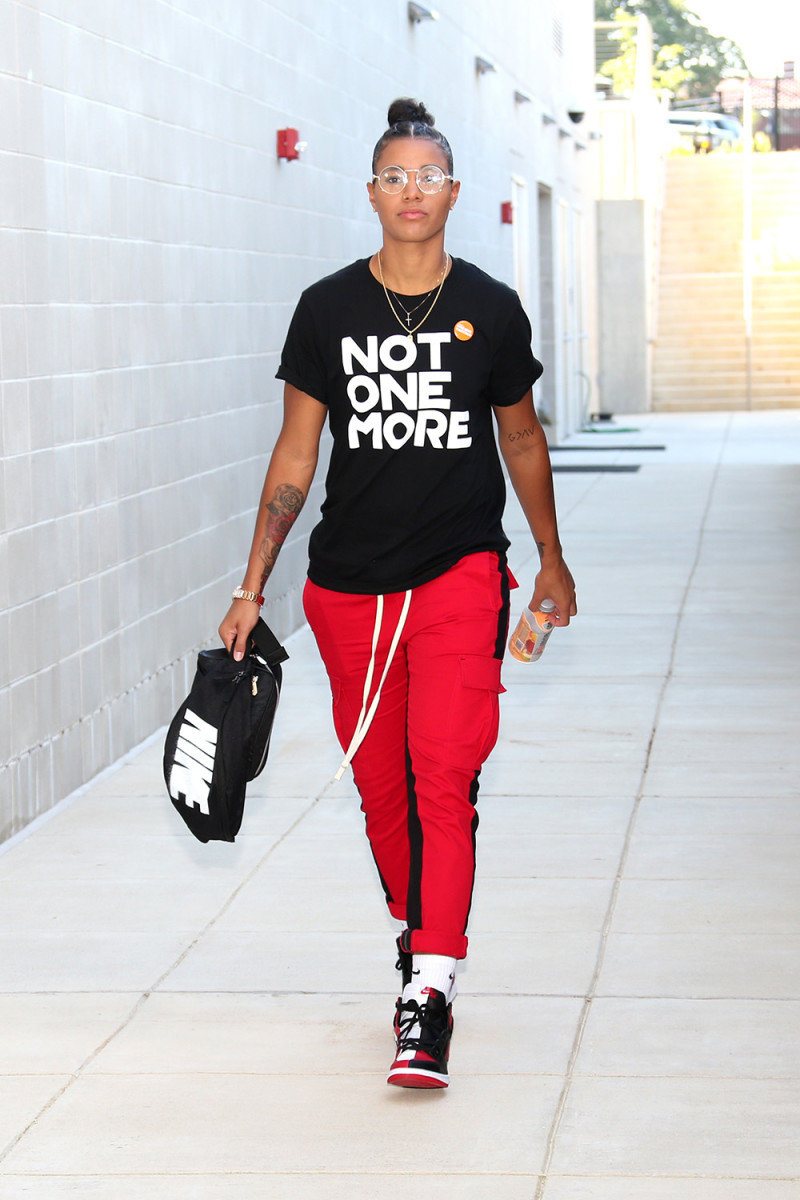

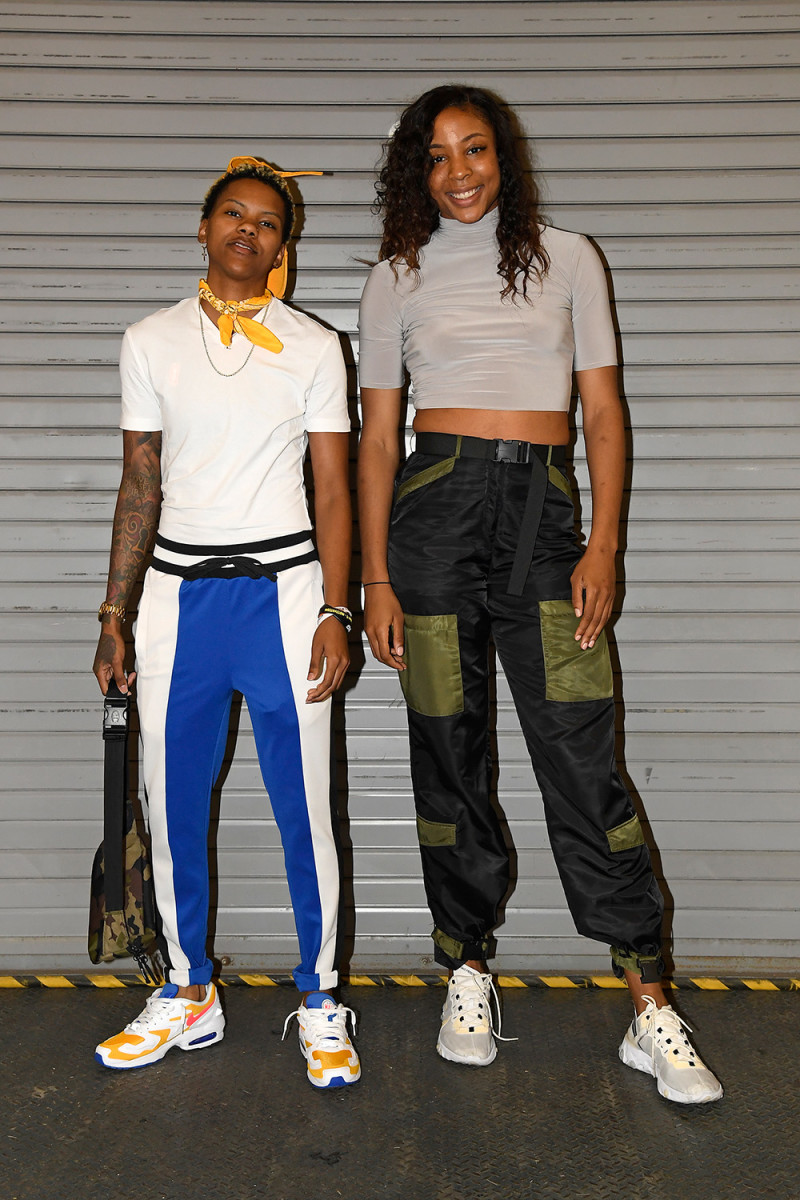

Whereas once, not that long ago, WNBA players were asked to sit through hair and makeup classes at rookie orientation, now they are free to express their style as they want. They can, as a New York Times op-ed put it, “celebrat[e] and showcas[e] androgynous swag.”

“People showing their personality is an amazing thing,” says Courtney Williams, guard for the Sun, who calls herself “one of the flyest” dressers in the WNBA. “It’s dope that we’re actually getting this recognition for how we dress, and not being put into a box where women have to dress a certain type of way.

“Swag is swag. Drip is drip.”

The summit was held in a private room at L’Avenue, a swanky French restaurant tucked near the Seine in central Paris. At the invitation of Johnson and fellow stylist Kesha McLeod, an all-star roster of modish athletes had gathered on the first night of men’s Fashion Week in mid-June: Newton, Taylor, Victor Cruz, P.J. Tucker, Rudy Gay, Travis Kelce and more.

Midnight passed. Dinner turned into drinks. Group pictures were taken, the Eiffel Tower as a backdrop. “There is an unsaid competition among stylists, and an unsaid competition among athletes,” Johnson says. “But us all being in Paris was a special moment. These guys would’ve never made the trip without having fashion as an anchor.”

When Johnson blazed a trail from the music industry to sports, luxury designers were paying little attention to athletes. “The fashion houses didn’t think that gentlemen of that size could represent their brand aesthetic,” she says. “Didn’t care if they had the money or not, didn’t care about the sport, didn’t care where they came from.”

But the game has forever changed. Harden regularly turned heads last season for wearing fresh-off-the--runway ensembles. Westbrook has released two collections with Barneys and created his own line, Honor the Gift, while Eagles safety Malcolm Jenkins was the brains behind a custom-suiting store in Philadelphia. And in January 2014 designer Riccardo Tisci themed an entire Givenchy menswear show around basketball, complete with court markings on the runway, a scoreboard, Nike hightops and jackets that featured basketball-like seams.

So, what next? Cruz, the salsa-dancing former Giants receiver and a Johnson client since 2012, has an idea. He is picturing a stage at Fashion Week built to resemble a stadium tunnel, models spilling off a bus and sashaying through metal detectors. Maybe there will be portable toilets. Or 10 trash cans.

“Honestly,” says Cruz, “the bowels of an arena don’t have to be that different from a runway in Milan.”