The story of how FOX hired a young Joe Buck for NFL when he had no football experience

The following is excerpted from LUCKY BASTARD by Joe Buck. Copyright © 2016 by Joe Buck. Used by permission of Dutton, a division of Penguin Random House Company. All rights reserved.

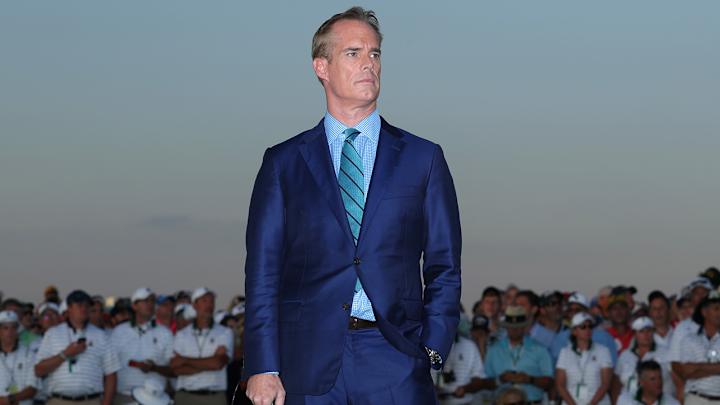

In December 1993, after my third year of doing Cardinals games, I got a huge break. But I didn’t realize it at first. I was too baffled to understand what was happening.

I was hosting a call-in show for KMOX when the news came across the wire: FOX had won the rights to the NFL’s NFC package. I couldn’t believe it. FOX? FOX didn’t do major events. That’s because FOX wasn’t a major network. It was where you found Joan Rivers, an adult cartoon show called The Simpsons, and Al Bundy sticking his hand down his pants on Married . . . with Children.

Lucky Bastard

by Joe Buck

My Life, My Dad, and the Things I'm Not Allowed to Say on TV

The NFL belonged on CBS, where Pat Summerall reminded viewers to “stay tuned for 60 Minutes—except on the West Coast.” And other than Monday Night Football, the NFC was the jewel of the NFL’s TV packages—the conference had won ten straight Super Bowls and featured most of the league’s marquee teams and biggest markets.

I expressed my astonishment and outrage to the tens of people who were listening to my show that night. KMOX was owned and operated by CBS. My listeners and I deserved an explanation!

The explanation came soon enough: “Hey, dumbass! Rupert Murdoch wrote a bigger check.”

Oh, is that how it works?

I was so busy being upset that I didn’t think about the fact that FOX would need announcers for these games. And I was an announcer. And . . .

Hey, wait a minute!

What if . . .

FOX Sports was run by an Australian named David Hill. He was basically building a network sports division from scratch. That was a big task, but it also meant David had the freedom and budget to hire the best people in the business. And since CBS no longer had an NFL package, David could poach a lot of CBS’s best talent.

David quickly hired the great Ed Goren of CBS to be his top lieutenant. Then David and Ed hired CBS’s top NFL broadcast team of Summerall and John Madden. That was brilliant, not just because they were the best, but because everybody knew they were the best. That shut up a lot of critics. It brought FOX Sports instant credibility. Fans could stop worrying that Bart Simpson would broadcast the Super Bowl. It was like if people said you couldn’t put together a rock band, and then you brought in Mick Jagger and Keith Richards.

David also hired producer Bob Stenner and director Sandy Grossman, who worked with Summerall and Madden at CBS. That was also brilliant. It smoothed the transition for Summerall and Madden.

FOX would have as many as seven games a week. Summerall and Madden would do the best matchup, for the biggest audience. Then David hired Dick Stockton and Matt Millen for the number two team.

That was a great start. But it was only a start. FOX Sports was like an expansion team that spends big money on top free agents but doesn’t have a farm system. Hill had to hire a bunch of lower-level announcers and producers—and quick.

Was I interested? I guess so, in the sense that everybody was interested. I didn’t think I had a chance. I didn’t really think I deserved one. I’d never done the NFL. I’d also never done college football. Or high school football. Or Tecmo Bowl. I’d never done football in my life.

At the Super Bowl a few weeks later, the most popular man in town was Ed Goren. Everybody and their mothers bombarded him with audition tapes.

Well, in my case, it was just my mother.

I did not attend the Super Bowl. But my dad was there to do the game for CBS radio, and my mom went with him, and she brought a tape of my work to give to Ed’s wife, Patti, whom she knew. My mom said, “You really ought to hear my son Joe. He’s good at doing baseball.” All I had really done was baseball and college basketball, unless you count the time I did a horse-jumping show, and what the heck, let’s just count that. It was not the best horse-jumping broadcast in history, but I studied enough to fake my way through it.

My mom never told me she was bringing a tape to Patti Goren. She didn’t tell my dad, either. I think she knew he wouldn’t approve. He would have told her to mind her own business.

Ed liked what he heard on the tape. But there was still the small problem that I had never done football. So he invited me to do a live audition at the new FOX football studio to see if I was any good.

To help me get ready, my dad had a videotape of a Saints game sent to us by a CBS affiliate in St. Louis. Bobby Hebert was the quarterback. My father and I sat in a living room in Florida during spring training and I did the game off TV with him. He had done decades of football over the years. I thought he was even better at football than he was at baseball. He had done Monday Night Football on the radio with Hall of Fame coach Hank Stram, and he did the NFL for CBS television and other networks. He was trying to teach me how to do it. He told me I was saying too much for a television presentation. I was telling our imaginary viewers the Saints were in the I-formation, or had split backs, or so-and-so was lined up in the slot. My dad said to keep it simple. I’d announce the down and distance, and maybe point out if a receiver was in motion, then be quiet until the play developed. I didn’t need to say, “Hebert drops back to pass.” Anybody watching the game could see he dropped back to pass.

I went out to Los Angeles to audition. I was twenty-three.

I rarely get nervous for a broadcast, but I was nervous for that audition. I knew it would determine the next chunk of my career, and maybe my life. I was young and married, with no kids and a huge opportunity in front of me.

At the audition in a television studio, I was introduced to Tim Green, who was just out of the game and was tackling his law degree. He obviously knew the game, but had never broadcast anything in his life. At least I had been a broadcaster. Tim hadn’t done anything.

At one point, they told us if we hit the talk-back button, we could talk to the producer, Bob Stenner.

Tim said, “What’s the talk-back button?”

He had no idea. This would be like getting on the pitcher’s mound, and the manager says to get the signal from the catcher, and you say, “Which one is the catcher?”

But I couldn’t fault Tim. It was all new to him.

We would watch video of a game from the previous season and do a fake broadcast. They gave us the names, numbers, heights, weights, and colleges for all the players—all the stuff broadcasters would typically get.

Once we started rolling, I was not nervous. I was a little bit out of my element, but I figured everybody was. It’s weird doing a game off TV in a studio. But the pressure didn’t cripple me. They rolled the game and pumped in fake crowd noise, and we just did it. This wasn’t radio. I didn’t have to create this picture for listeners. I had to accent the action.

I knew, as the game went along, that it was going well. I was young, but I had been around the business long enough to know when a broadcast is going well and when it’s not. I felt comfortable, not rushed or forced. I was anticipating the action and getting my facts right. I felt like I did during a baseball game—whatever happened, I knew what to say.

When Tim and I finished, we put our headsets down. George Krieger, an executive who worked with Ed and David, told me: “We’re going to hire you. Do you have an agent?”

I thought: “An agent. Right. I guess I need one of those.”

I hired Jim Steiner. He didn’t have any broadcasting clients, but he lived in St. Louis and I knew him. He didn’t have much leverage with FOX. There was no competition for my services. Jim got me a few perks, which I appreciated, but that was all he could realistically do. FOX thought I was lucky to be hired at all, and FOX was right.

Tim Green did not get an offer that day. He and I went to Denny’s after our audition and we sat there: me knowing I was getting hired, him unsure. I was excited, but I couldn’t let it show, because I didn’t want him to feel bad. But pretty soon, he did get an offer from FOX. And we were paired together for two years, which was great.

We did one preseason game as practice. It never aired—it was just for us to get some work in. I called the game exhibition football on the (fake) air, and I was told that was wrong. It was preseason. Apparently, that sounds more important.

Our first real game was the 1994 season opener at Soldier Field. As I heard somebody in my earpiece counting down to the first segment, I thought: “What in the hell have I gotten myself into?” I didn’t know if I could do it. But within a few minutes, I stopped thinking about it. I just did the game.

Tim was so new to broadcasting that I was basically his on-air tutor. When he said something, I would give him a thumbs-up or thumbs-down—you can only imagine how the old-guard TV critics would have reacted if they knew that. And I didn’t even really know what I was doing. So my dad would tell me what to tell Tim, and then I would tell him.

But Tim listened to me. I’ve learned, working with a lot of ex-athletes on the air, that for the most part they want a scoreboard. They want to be critiqued. They are used to being coached and they want that. I don’t overdo it, but when it’s appropriate, I will say something.

Summerall and Madden were the number one team. Dick Stockton and Matt Millen were number two. We were the number three or four team, depending on who was doing the ranking. But I felt we would only move up over time. I hit it off with the executives. I felt comfortable.

I also felt I was working at the right network. Only FOX would have hired me at that age to do the NFL when I had never done football.

I quickly learned that it was great to work for a place that was starting from scratch, because FOX was not married to some of the stupid policies that were standard at other networks. Everybody in the history of the sports broadcasting business had fudged expense reports. FOX’s solution: no expense reports. We got a certain number of dollars per day. FOX had a car service pick us up at the airport and take us where we needed to go. Nobody could claim it took six cabs and $427 to get from the airport to the Hyatt. FOX cut the bulls***.

The first year was as seamless as I could have hoped. I really was just trying to get through it without anybody realizing I didn’t know what I was doing. Thankfully, I was about to get some help.

Tim Green and I did a practice preseason game in Chicago in 1995. After it, I was walking out of the stadium when a long-haired man shook my hand and said:

“I wanted to introduce myself. I’m Steve Horn. I knew your grandfather. I know your dad. I’ve worked for [Bob] Costas forever. I work at FOX now. If you ever need anything, give me a call.”

Horn was doing editorial consulting for FOX NFL Sunday. He was a behind-the-scenes guy, helping with story lines and finding material for the announcers on the pregame show. He had this huge network of scouts for NFL and baseball to tell him what was really going on. He would tell the announcer how a pitcher adjusted his grip for his breaking ball, or why a quarterback wasn’t the right fit for his new offense—stuff you usually don’t see in a newspaper but which is invaluable for broadcasters.

I called Horn a couple of times during ’94 and ’95, to get a different angle on whatever game I was covering that I was doing with Tim Green. I did not yet realize that he would become one of the most important people in my career, and in my life.

In November 1995, FOX landed another big sports-rights deal: The network would share rights to Major League Baseball with NBC. This did not stun the industry like the NFL deal. FOX had already shown it could do sports. People had already shown they could find FOX on their TV as easily as they could find CBS or ABC if they wanted to watch a game.

And this time, I knew right away that I wanted to be part of the broadcasting mix. I was established as a football announcer with FOX already. Suddenly, I had an advantage over every other job candidate: I was in-house, and I had done a lot of baseball. I had done all 162 Cardinals games per year before I started doing football for FOX, and I was still doing 140. I knew as soon as FOX got baseball that I would be involved. This wasn’t like when FOX got the NFL and it never occurred to me that I might work there.

FOX made me the lead play-by-play announcer, which meant I would do the Game of the Week on Saturdays, play-off games, and the World Series when FOX had it. It was a dream, except for one detail.

My partner.

Tim McCarver.

I think it’s fair to say Tim would not have been my first choice. He would not have been in my top 100, to be honest, and it had nothing to do with his ability. I knew he was very good. But I think you get more protective of your family than of yourself, and I was still upset with how Tim had treated my dad—more upset, I think, than my dad was.

This had the potential to be awkward. But what was I going to do? I certainly wasn’t going to turn down the chance to broadcast the World Series on national TV because of an old grudge.

I decided Tim and I needed to clear the air. Before the season started, we went to our first FOX baseball seminar. Then we went to dinner as part of a big group. I said, “Come over here.” At the time, I was 26. He was 54. He was the veteran. I didn’t care. I said, “Look, we need to have a drink. Let’s just figure this out now.”

Joe Buck reveals that hair plug addiction nearly cost him his career

We had a drink, and I said, “I know things didn’t go well with my dad. But you and I are going to be judged on how we do together. You know what I think of my dad, how I adore him. But I’m bigger than that. You’re bigger than that. Let’s just go forward and see what we do together as Joe and Tim, not Jack and Tim, or not Jack’s son Joe. Just Joe and Tim.”

We shook hands. He was great. We never discussed what happened between him and my father. There was no need. We both knew it hadn’t worked. And he had talked to Mike Shannon, and Shannon told him, “You’re going to love working with Joe. He’s different than Jack.” I think Tim went in with a good attitude. We hit it off immediately. I loved working with Tim. We never had one cross word in the eighteen years we worked together.

I would never have predicted this in 1991, but Tim McCarver became a friend. He is my friend, to this day. But we are not the kind of friends who socialize together. This story may help explain why.

Shortly after we were paired, we went out for dinner the night before a game in Boston. I was late to dinner. So I was the last one in our party to arrive at this seafood restaurant. Everybody else was already seated.

I took the only open seat, next to our producer, John “Flip” Filippelli. Filippelli and McCarver never got along, pretty much from the moment they started working together. They clashed nonstop, to the point where I, the guy in his twenties, was basically mediator between Tim and Flip. It was awkward. I was still trying to find my way, and I had to make sure that the producer and the main analyst wouldn’t punch each other.

I’d never witnessed anything like it in this profession. I tried to tap-dance back and forth to ease the tension without violating anybody’s trust. Later, we were in Cleveland before a play-off game, and we were supposed to meet at a production truck, and Tim got there a few minutes late, and Flip snapped at him for it. But Tim had been talking to players in the clubhouse. It wasn’t like he was goofing around. Stuff like that happened all the time.

I felt like Filippelli should have tried a little harder to get along with Tim, since Tim was the one performing on air, and really was the one that gave us credibility. But that was between them.

Anyway, I sat down with Flip, Tim, and the crew. I ordered this huge lobster claw, and when I finished, it was dripping in butter. I wrapped a napkin around it, and while Filippelli was looking the other way, I slipped the lobster claw wrapped in the napkin into the inside pocket of the blazer on the back of his chair. I was giggling to myself. I wasn’t that far removed from being a Sigma Nu at Indiana, and even though I never graduated from college, I got a master’s degree in doing stupid s*** to my friends for my own amusement. Flip and I had the kind of relationship where we could play jokes on each other and laugh about it.

After we were all done and the check was paid, everybody got up to leave.

McCarver reached over, grabbed the blazer on Filippelli’s chair, and started to put it on.

They had switched seats before I got there.

I was mortified. I knew Tim well enough to know you did not prank him like that. He was big on leaving his stuff alone. As he put the coat on, he felt this bulge in the inside left pocket of his jacket, and said, “What the F***? I mean, God-DANG!”

He pulled out the napkin, and as he was unwrapping it, I jumped in and said, “Tim, I thought it was Flip’s coat. I’m sorry. I’ll buy you a new blazer.”

To Tim’s credit, he said, “It’s fine. It’s great.” And he laughed. But I know inside he wanted to rip my head off, because that was just not a trick you play on Tim McCarver.

The coat was not ruined. I think he wore it in the play-offs for the next six years. But we rarely went to dinner together after that, and it’s not because he was pissed. He wasn’t. We just have different personalities. I was far more likely to go out to dinner with my other teammate in the booth, the one nobody ever saw.

Steve Horn doesn’t appear on TV. I had used him as a resource only sporadically on the NFL. But when I got the baseball job, he called me and said, “I’ve covered baseball with Costas. It’s kind of in my wheelhouse. I’d love to work with you and for you. Is that something you’d be interested in?”

I was definitely interested. I needed all the help I could get. I was in my mid-twenties and would be doing the World Series on TV. I wanted safety nets under my safety nets. I didn’t want to get four innings into my first game and realize I was comparing every situation to something that happened to the Louisville Redbirds. If Steve Horn was good enough for Costas, he was more than good enough for me.

Before long, Horn was off FOX NFL Sunday and working primarily with me. It’s hard for outside people, even people at FOX, to understand what he does. The simple answer is that he makes me look good. And that ain’t easy.

When I prepare for a game, I go through the notes provided by the teams, and stories provided by SportScan, a subscription service that sends me all the published stories about specific teams. I get a stats packet on the game I’m doing from STATS—the first four pages are team and league notes, and the next eight are individual notes on players. Then I lean on my own conversations with people in the sport, and all the information Horn gives me, the behind-the-scenes analysis that only he seems to know.

Steve looks like Tommy Lee Jones playing Joey Ramone in a movie. He has worn the same outfit since I met him: jeans, an Oxford shirt, leather jacket, and black biker boots. I mean, in twenty years, he has not changed his wardrobe. He is the fashion industry’s worst nightmare. His face hasn’t changed much either. He is in his sixties but looks younger than fifty.

People sometimes ask if Horn gives me stats. That’s like asking if Tom Brady is the guy who hands the ball to the tailback—he is, but that doesn’t really capture his value. Anybody can look up statistics. I can have my nephew do that. Horn takes information and puts it together in a way that makes telecasts more interesting.

Horn grew up in St. Louis, but he went to Columbia and even drove a taxi in New York for a while. You don’t see too many Columbia grads driving New York taxicabs. That’s a pretty small demographic.

Horn gave me a New York sensibility. I felt I was always trying to please the New York critic. Whether it was Richard Sandomir of the Times, or Bob Raissman of the Daily News, or Phil Mushnick of the Post . . . I felt that, if you can pass their test, you pretty much can pass the test of the rest of the country. (Passing Rudy Martzke’s test was also important, but for some reason, Martzke was a lot nicer to me than he was to my dad.)

Horn gives me a different point of view than the Midwest, conservative viewpoint that I would typically bring into something.

We meet all the time for lunch. He’s kind of like my tutor. He’ll ask me about the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and explain to me the workings and the history of that. Or he’ll say certain Middle Eastern countries are basically corporations with flags, and that explains their interactions.

He has a smart way of looking at current events that I wouldn’t have by just reading. He reads The New York Times every day. He highlights it and takes notes. He reads the front section and the Arts or Living section before he goes to the sports. But he can also tell me about the running style of Gale Sayers, or what made Sandy Koufax special, or what baseball was really like in the early 1960s. He has a way of contextualizing moments that might otherwise seem flat. When he sits next to me in the booth, I feel like I have the smartest guy in the room on my side. When I do football games, Horn has a headset and can talk directly to me.

After cancellation of HBO show, Bill Simmons faces uncertain TV future

One day in the mid-nineties, early in my FOX career, Horn asked me to go to lunch. When we sat down, he said:

“I’m going to tell you two things you’re going to be mad about. You may not like me after this. But as your friend, as somebody who works with you, I feel like I need to tell you this. You can punch me in the face, or you can accept what I’m about to say.”

Great. What is it? Do I suck?

He said, “First, you need to lose about 30 pounds, for two reasons. One, you’re going to be on TV. Nobody likes looking at a fat guy on TV. Fat guys don’t really exist on TV for the most part.

“Two, your dad is a Type 2 diabetic. The lighter and thinner you can be, the more chance you have of fending that off. You’re predisposed to all these things. You need to give yourself a fighting chance.”

I decided not to punch him for that. He was right. It made sense. If you look at those tapes from 1995 and 1996, I am fat-faced. People want to see somebody on TV who is attractive, or at least not unattractive. And speaking of which . . .

Steve said, “And I think you need to look into getting hair plugs.”

My hair?

“Funny you should say that,” I said.

I told him I had already had some fresh sod laid down, and planned to continue the lawn maintenance in the future. So I didn’t punch him for that, either.

You already know about my hair obsession. But I needed to think about my weight just as much. I am 6'1". I weighed 240 pounds at age 19, and if you weigh 240 at 19, you are in danger of weighing 340 at 39. Metabolisms do not magically improve as you get older. I am programmed to be chunky. Who knows what I would weigh right now if I hadn’t started watching my diet? So I started to watch everything I ate, and I still do. Steve’s comment was the best advice he ever gave me.