Michael, Murray and ... OJ? Ahmad Rashad Has Kept His Celeb Friends Close—Most of Them, Anyway

This story appears in the July 2, 2018, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine — and get up to 87 percent off the cover price plus two FREE gifts. Click here for more.

“Adam Silver, he’d be one . . . . Bill Murray. But he’ll be hard to get ahold of . ...”

Ahmad Rashad is listing the people I should talk to for this story. “Michael, we’re next door neighbors,” he says. “We spend all our time together. All our time together!” He doesn’t feel the need to clarify that Michael is Michael Jordan. He’s also aware that this could turn out to be a useless exercise. “Man, s---,” he says, “My friends won’t like having their phone numbers get out.”

Such is life for Rashad, the former sportscaster who seems to know everybody. In the 1990s he was NBC’s sideline reporter for the NBA; he was half of a celebrity couple with Phylicia Rashad, co-star of The Cosby Show; and he had a Gumpian tendency to turn up unexpectedly in pop culture, thanks to his famous friends.

When I call Rashad about doing a story, he sounds excited. He rattles off what he’s doing now: working as a corporate spokesman, hosting special events for the NBA, playing lots of golf. He invites me to interview him during the NBA Finals. He’ll think of more people I can talk to then, once he starts telling some stories.

Rashad and I meet twice for lunch at the Ritz Carlton in downtown Cleveland. He greets me with a smile, and my first thought is that he’s bigger than he appeared on TV. He’s 6'2" and well built, even now at 68. He still has the big doe eyes, the square jaw and an earring in his left lobe. Rashad tells me about the time he found himself in a crowded elevator with his friend Muhammad Ali. This was in 1996, when Ali was in the throes of Parkinson’s and he could barely speak. Ali leaned over and whispered in Rashad’s ear, “You know, we two pretty motherf------.”

Pick almost any celebrity from the 1970s, ’80s or ’90s, and Rashad has a story. “I feel like I know a lot of people,” he says. “But I must’ve made an impact on them, for them to want to know me, too.”

Many people don’t know that Rashad was a football star in college, perhaps because he was called Bobby Moore until he followed Ali and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and changed his name in 1973 after converting to Islam. As Bobby Moore, he was an All-America running back his senior year at Oregon and was then picked fourth overall in the ’72 NFL draft by the St. Louis Cardinals, who used him as a wideout. He played in the NFL for 10 years and made four Pro Bowls with the Vikings as Ahmad Rashad. He’s in both the College Football Hall of Fame and the Vikings Ring of Honor. “He was clearly the best player on our team, and one of the greatest players Oregon’s ever had,” says Hall of Fame QB Dan Fouts, Rashad’s college teammate.

It was in Eugene that Rashad made one of his first famous connections. Jack Nicholson came to campus to direct his first film, Drive, He Said, a movie about a star athlete’s sex life, and someone introduced him to Rashad. “He’s a big sports fan, I was The Guy on campus, and we just hit it off,” Rashad says. When Nicholson wasn’t working, he would hang out at Rashad’s apartment. He followed Rashad’s career after that, sending him notes or calling him after games.

“Then the thing expands,” Rashad says. “You end up knowing who he knows. I never stopped to try to figure that out.” It helped that he spent his NFL off-seasons living in Los Angeles. His circle grew to include everyone from Arthur Ashe to Sammy Davis Jr. to Sidney Poitier. They bonded initially over sports, then over life.

Rashad’s friends say he has a wide-eyed curiosity and youthfulness about him, as if he’s forever the little brother, tagging along. “He’s sort of a boy, in a funny way,” says Murray, one of his closest friends. “He looks kind of ageless anyway. And he can giggle. He can just start laughing—he’s got a lot of different laughs, actually—but when you get the big, deep laugh, he really sounds like a kid.” Phil Knight, the Nike founder, puts it like this: “He never pays and everybody still likes him.”

That curiosity served Rashad well as he cultivated these relationships. “It’s always interesting to talk to people who have done something,” he says. “People you never thought in a million years you’d be close to, but you act like, I belong here.”

One time Rashad recalls visiting Las Vegas and going to a Bill Cosby show and the star inviting him to his dressing room. There was Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and the rest of The Rat Pack. “AH-mawd RAH-shawd,” Sinatra said in his smooth baritone. “I’ve been watching your career.”

“Then I couldn’t hear—I went deaf,” Rashad says. “I’m smiling like an idiot. He says, ‘Come on over here and sit down.’ I sit next to him and he starts talking, and I’m just thinking, This is f------ Frank Sinatra. He asked me a question and I’m just like [guttural sound]. I don’t even know what I said! Then Lauren Bacall’s like, ‘You’re so cute.’ ”

Rashad tried his best to play it cool. On the table in front of him was a bowl of guacamole and chips; in the corner a chef was making sushi. Rashad reached for a chip, took a big scoop of guacamole, and felt Sinatra watch him take a bite. “A half-second later,” Rashad says, “my head explodes.”

Sinatra howled: “This cat loves him some wasabi!”

Everyone was getting to know the name Ahmad Rashad. I ask him about his conversion to Islam, and he doesn’t talk about having a revelatory moment after growing up in a Pentecostal home in Tacoma. What Rashad brings up is the backlash. He was the first football player to join this movement, and this was a time when players “didn’t have any sort of substance,” he says. He still remembers his first game in St. Louis as Ahmad Rashad, which in Arabic means “admirable one led to truth.” When the P.A. announcer introduced him, “The whole place was booing like crazy,” says Rashad. “And when I went to stand next to the guys, they were moving away from me, too!” After the game, security had to walk him to his car.

During that trying time, Rashad leaned on his good friend, Bills running back O.J. Simpson. Rashad details their relationship in his autobiography, Rashad, which was published in 1988, when he was 38 and about to enter his prime as a broadcaster. According to the book, they met at the Hula Bowl around Rashad’s senior year at Oregon, and then spent an offseason together in L.A., working out, partying and chasing women. After Rashad changed his name, Simpson would call him, listen to him vent and offer encouragement. As the backlash built in St. Louis, Simpson successfully lobbied Buffalo to acquire him. The Bills came to accept Rashad, he writes, because O.J. vouched for him. Rashad spent only one season in Buffalo, but that rebuilt his reputation and led him to Minnesota, where he spent his best years in the NFL. Any stigma that had been associated with his new name evaporated.

Simpson’s supportiveness stayed with Rashad for years. On June 17, 1994, he was preparing to work Game 5 of the NBA Finals at Madison Square Garden when Simpson took off in his white Ford Bronco, pursued by the LAPD. For about 45 minutes, Rashad went missing. Dick Ebserol, the president of NBC Sports, went looking around the bowels of the Garden and eventually found Rashad back where the circus animals were caged during basketball games. “It had a unique odor, as you can imagine,” Ebersol recalls. “And here was Ahmad, fully attired in a coat and tie, sitting on hay bails, weeping. Because he had figured that O.J. would not survive being chased around that night. Ahmad, just like a friend would, had gone off by himself to weep over the predicament that his friend had put himself in.”

Simpson had mentioned Rashad in the note he had left behind: “Ahmad, I never stopped being proud of you.”

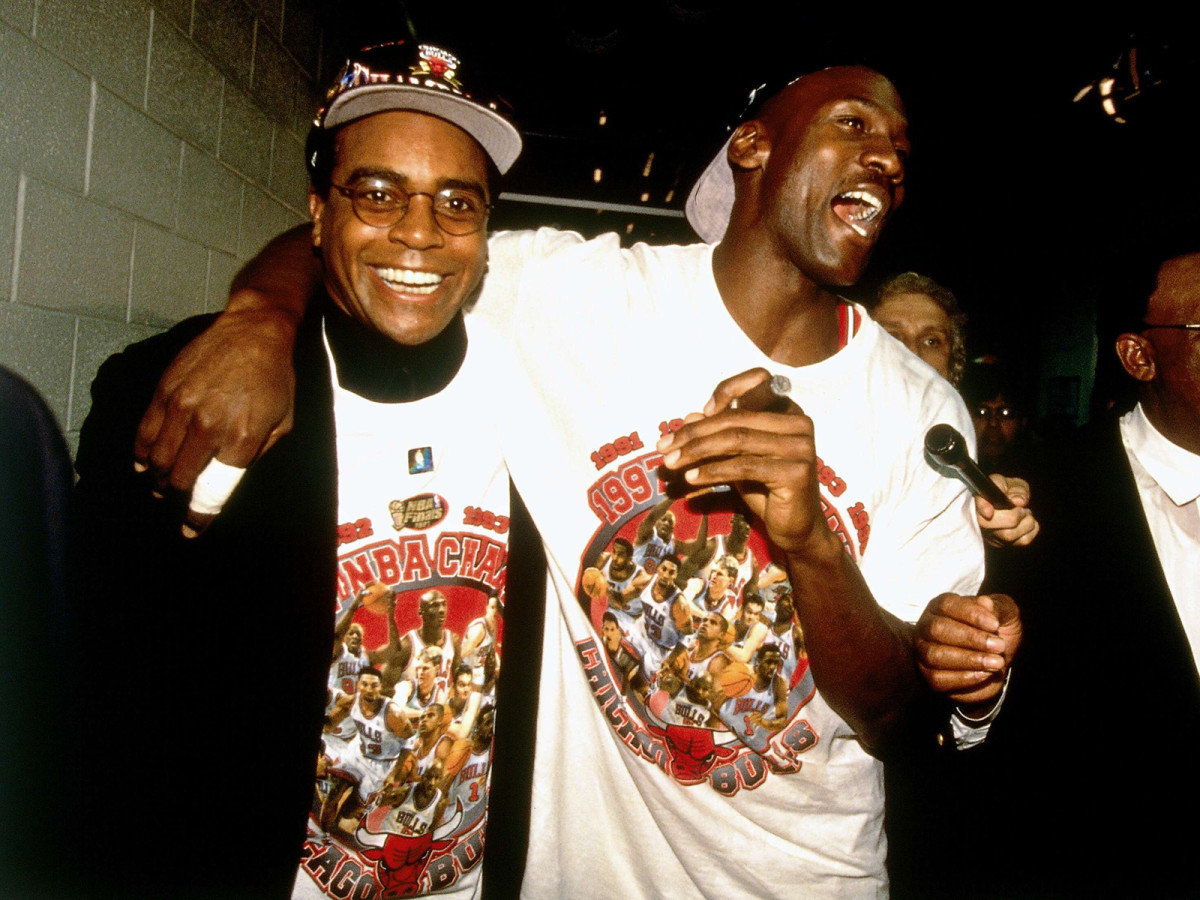

Of all his famous friends, Rashad is most closely associated with Michael Jordan. They met around 1989, Rashad says, at a Magic Johnson charity basketball game in L.A. NBC was in the process of acquiring the rights to broadcast NBA games, and Rashad was covering the game. The two exchanged numbers, simple as that.

“I think they both have a wry sense of humor, and they’ve both had enough celebrity in their life, enough adulation in their life, that they don’t need any fluffing on the outside,” says Murray. “Ahmad has been sort of through the tunnel. You crash into a lot of the same people.” (Jordan declined to comment for this story.) The way Rashad describes it, they were like “big brother-little brother, but we would switch. Had he not been a basketball player, we still would’ve been best friends.”

At that point, NBC had been using Rashad in a number of ways: as an NFL commentator, as an Olympics host, as a worldwide sports correspondent. In 1990, Ebersol proposed having Rashad anchor a new Saturday morning NBA show targeted at young viewers. “A football player?” commissioner David Stern replied. “On a basketball show?” For the next 15 years, Rashad served as the host of Inside Stuff, going behind the scenes with the league’s stars. “He booked his own interviews,” says Adam Silver, Stern’s successor, who oversaw the show on the league side. “He had those relationships to get directly to players.” Ebersol also installed Rashad as the sideline reporter on the NBC game of the week. This was before cable took over and network shows were must-see TV. It became a reccurring image through the ‘90s: Rashad interviewing Jordan on the court after another big game. “His mere presence, without having to explain it, evokes an era,” says Bob Costas, who worked with Rashad on those NBC broadcasts. “It’s almost like when people hear Da na na na na NUN na na … they know! It just evokes an era.”

Other reporters criticized Rashad for being too close to Jordan, for losing objectivity; Rashad says they were just jealous. When he covered games in Chicago, he would stay at Jordan’s house. They’d would work out together and drive to the arena, where Rashad would chat up coach Phil Jackson and the players. “It was cool to be familiar with that whole group, see it from the inside,” Rashad says. “Most reporters don’t get that. There’s a line that they can’t cross. For the entire Bulls’ [run], I didn’t have that line . ... It was like I was a member of the team.”

Surely Rashad has some good Jordan stories, but none that he tells are too revealing. That’s why he was able to get and stay so close. Jordan knew he could trust Rashad. “I didn’t have to say anything was off the record,” Rashad says. “I played. I know how it works. I know what you report and don’t report.”

On road trips Rashad and a select few would hang in Jordan’s hotel room after games. In the hours after the Bulls won their sixth and last championship, after MJ hit the buzzer-beater over forward Bryon Russell, they were celebrating and smoking cigars in a Salt Lake City suite. Jordan tried playing piano and people sang along, and Ahmad Rashad soaked in another indelible moment.

I ask Rashad how he broke into the TV business, and he says it’d been a long-time plan of his. He worked part-time at a Twin Cities TV station the last five years of his career. When he retired from football at 33, he says he had job offers from all three major networks. “I wanted to represent African-American athletes in a better way than what I saw when I grew up,” Rashad says. “Because every time I saw them, nobody could talk. They sounded like they never went to school. And I wanted to carry that torch, that you could be an African-American [athlete] and you could be smart. You can have a personality. You can speak.”

One of his mentors in television happened to be the most prominent of African-American celebrities: Bill Cosby. As with Nicholson, the two met when Rashad was in college and Cosby was passing through Eugene. “Bill was the first important person to steer me toward television,” Rashad writes in his book. Cosby would warn him: “Don’t get stuck just playing that football. Don’t let a game run your life.” When both of Rashad’s parents died in 1980, Cosby started introducing him as his eldest son. “He did it in a lighthearted way,” Rashad writes, “but it always made me proud.”

Cosby also tried repeatedly to fix him up. “He’s like a Jewish mother when it comes to worrying about his single friends,” Rashad writes. After a series of failed attempts, he begged Cosby to set him up with his sitcom co-star, Phylicia Ayers-Allen. Eventually, Rashad proposed to her on live TV, during the NFL pregame show on Thanksgiving, 1985. If he was already famous among sports fans, the proposal and subsequent wedding to the star of a hit show made him a household name.

In the book, Rashad describes his wedding day in detail. Cosby escorted Phylicia down the aisle of a Harlem church, walking with a fake limp to get laughs. At the altar Simpson, the best man, looked at the bride and whispered in Rashad’s ear: “I wasn’t so sure about this before, but now I see why you’re marrying this lady. She’s gorgeous.” Then, as Cosby took his place next to them, he hit Rashad in the crotch, trying both to be funny and to send a fatherly message: Don’t mess around on my girl. “I mean, he really nailed me, and I nearly doubled over,” Rashad writes. “I stood there gasping for breath.”

The book also includes a back-and-white photo of the wedding party. There’s Rashad in his tux, and standing next to him, one at each side, are Cosby and Simpson. “My biggest moment,” the caption reads.

Rashad’s life now is not too different from many sexagenarians’, if it weren’t for all his famous friends. He recently married for the fifth time (he and Phylicia divorced in 2001); he has five children (four of whom are grown); and he lives in Jupiter, Fla.—across the street from Jordan. They try to get in 36 holes whenever they can, playing with Tiger Woods, Rory McIlroy or Justin Thomas on a semiregular basis. (Rashad is a four handicap.) They’ve also gone out about a dozen times with President Obama.

“Ahmad will probably go over [Jordan’s house] and watch games,” says Howard White, Jordan’s longtime Nike liaison who was one of the hotel room regulars. “They’ll probably have a cigar together. I would assume they’re doing a lot of those same things. It’s just, they’re not his games to get together and celebrate anymore.”

Jordan may be Rashad’s closest friend, but after reading his book, you could argue that his two most influential friends were Simpson and Cosby. One helped save his football career, the other helped kick-start his TV one. Rashad has not brought them up at all, though, as you would expect, considering one spent nine years in prison for assault, armed robbery and kidnapping after standing trial for the brutal murder of his wife, Nicole; and the other is awaiting sentence after having been found guilty on three counts of aggravated indecent assault.

“He’s always been very close-lipped about those incidents,” Murray tells me, “and I have no interest in asking him about it.”

When I bring up Simpson and Cosby, Rashad is taken aback at first. Then I mention that I’ve read his book, and he realizes that I know the extent of his relationships with them. “Here’s my feeling about that,” he says, “everybody has their cross to bear. Those two guys’ crosses are pretty f------ heavy. And that’s all I have to say about it.” He pauses, and then continues: “I’m sure they knew a lot of people. Maybe you just didn’t know them as well as you thought you knew them. You just don’t know. I’m as devastated as everyone else with these two people. It’s like, holy s---. They were in chapters [of my life]. So were a lot of other people. They weren’t the main characters. I’m the main character in my own book. Those two things are just ... maybe the most ... oh, I can’t even describe it. It’s just ... heartbreaking all around. And not so much for them, but the victims. It’s like, that’s f------ crazy. But like I said, that’s their cross.”

Rashad says that he had a falling out with Simpson around 1988 over a personal issue he doesn’t want to discuss and that he hasn’t spoken to Cosby in years. “In your journey,” Rashad says, “of all the people that you know, you can’t single out two people and say they have more weight [than someone else]. That’s no weight. That’s throw-away weight.” He’s told me all these stories, about all these people, why focus on them? “I played football with a guy who ended up killing people—what does it have to do with me?” he asks. “I didn’t kill nobody. And then the other guy who’s been accused of doing some unconscionable s---.”

Rashad would rather speak of the happy moments—rallying with John McEnroe, taking John Candy to the Super Bowl, hanging with Glenn Frey at Studio 54. He’s done with Cosby and O.J. He’s revising them out of his life right here, right now. I ask him if he knows that the picture from his wedding—the one with him, Cosby and O.J.—is going around the Internet. “Yeah, I’ve seen that photo,” Rashad says, “and the only people I see in it are me and my wife. I don’t see those two f------ guys. They’ve disappeared out of my memory. I’ve erased them out of my consciousness.”

A few days later Rashad invites me to see Saint Joan on Broadway. His daughter with Phylicia, Condola Rashad, is playing the lead, Joan of Arc, a performance for which she received her fourth Tony nomination. She also has a recurring role on Showtime’s Billions. As the curtain closes, Ahmad is the first person out of his seat, clapping hard and beaming.

After the show, in Condola’s dressing room, Ahmad and his daughter discuss their plans for tomorrow with Ahmad’s wife, the therapist Ana Luz Rashad. Ahmad is going to the Tonys as Condola’s date, and they’re all supposed to meet before the award ceremony at a restaurant across the street from the theatre—the same one that had turned Ahmad away just a few hours before because he didn’t have a reservation. Condola had told him to say he was her father, but Ahmad refused. Condola explains that the restaurant will do favors for the cast, since the show gives them so much business. But Ahmad is afraid he’s going to be turned away regardless.

He played tambourine onstage with Jimmy Buffett. He took putting lessons with Joe Pesci. He used to be a regular at Elaine’s. Now he can’t get a table at the Glass House Tavern?

“How are we getting in that restaurant?” Ahmad asks, and Condola just gives him a look.

“We’re not gonna do that,” he says. “I’m not going to walk up there and say ... ”

“Daaad, just go and do it.”

“Uh-uh. Nope. I’m not doing it,” Ahmad says, shaking his head and staring at the ground. He suggests that Condola have one of her half-sisters drop her name first.

“Dad!”

“I’m not doing it!” he says, laughing. “They’re going to tell me to get out of here.”

“Dad, it’s fine.”

“‘Excuse me, sir, we don’t care who your daughter is, we’re not letting you in the restaurant.’”

“‘Nor do we care who you are ... ’” Ana Luz chimes in.

“Yeah,” Ahmad says, “they don’t care, either.”

Say this about Ahmad Rashad, he knows the value of a name—when to change it, how to develop it, and what it can come to signify over time, especially in the company of other names.