Rocky Gets Right: How Creed (and Michael B. Jordan) Give the Boxing Franchise New Life

This story appears in the Dec. 3, 2018, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

The kids sitting in the front of the CityPlex12 theater in Newark are excited, very excited, because Michael B. Jordan is here. It’s a Monday night in Jordan’s hometown, and the actor/sex symbol/cultural icon has invited three theaters full of guests to a private screening of his new movie, Creed II, the latest entry in the Rocky franchise. The first two rows are taken up by the She Wins Scholars, teenage girls from a social action organization that serves children affected by inner-city violence. They’re wearing iridescent head wraps and incandescent smiles, and before Jordan entered the theater they had their fists balled and their biceps flexed, emulating boxers. Now they’re gasping and shrieking as he walks past. They rush toward him, their palms clasped over their mouths, grabbing hold of his arm, his shoulder, his hand, refusing to let go. Jordan brushes away his concerned security detail. It’s O.K., he says. It’s good.

The guests here tonight are from his old high school and his old church, from community centers and from youth groups; they are young and old, male and female, and they’re proudly celebrating black culture—Bantu knots and protective-style braids, natural curls flowing freely, Malcolm X and Colin Kaepernick T-shirts. But while the young fans up front are excited, those in the back of the theater—the parents and the grandparents, the ones who remember Rocky entering the cultural lexicon 42 years ago—are something else. They are proud.

“We love you, baby!” a woman with close-cropped silver hair yells out. “God bless you!”

There are hugs, so many hugs, as Jordan winds his way around the room, like a family gathering on the holidays. Some dab tears. Others simply let them fall. To everyone in this room Jordan is the new Rocky. Their Rocky. But also, no, he is not.

As the Creed II script has it, Jordan is Adonis Creed, son of Apollo, doting fiancé to Bianca, loving father to Amara, heavyweight champion of the world. And as these fans leave the theater tonight it will be hard for them to distinguish between the man they are screaming for now and the character they screamed for as the movie played out on the screen.

Rocky is an anomaly in movie history. “A one-off,” says Stephen Leggett. “It doesn’t fit into any category.” Leggett is the program coordinator of the National Film Registry, an advising body to the Library of Congress that chooses movies “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant and worthy for preservation.” In 2006, the original Rocky film became one of the 725 movies included in the registry, alongside the likes of Citizen Kane and Gone with the Wind.

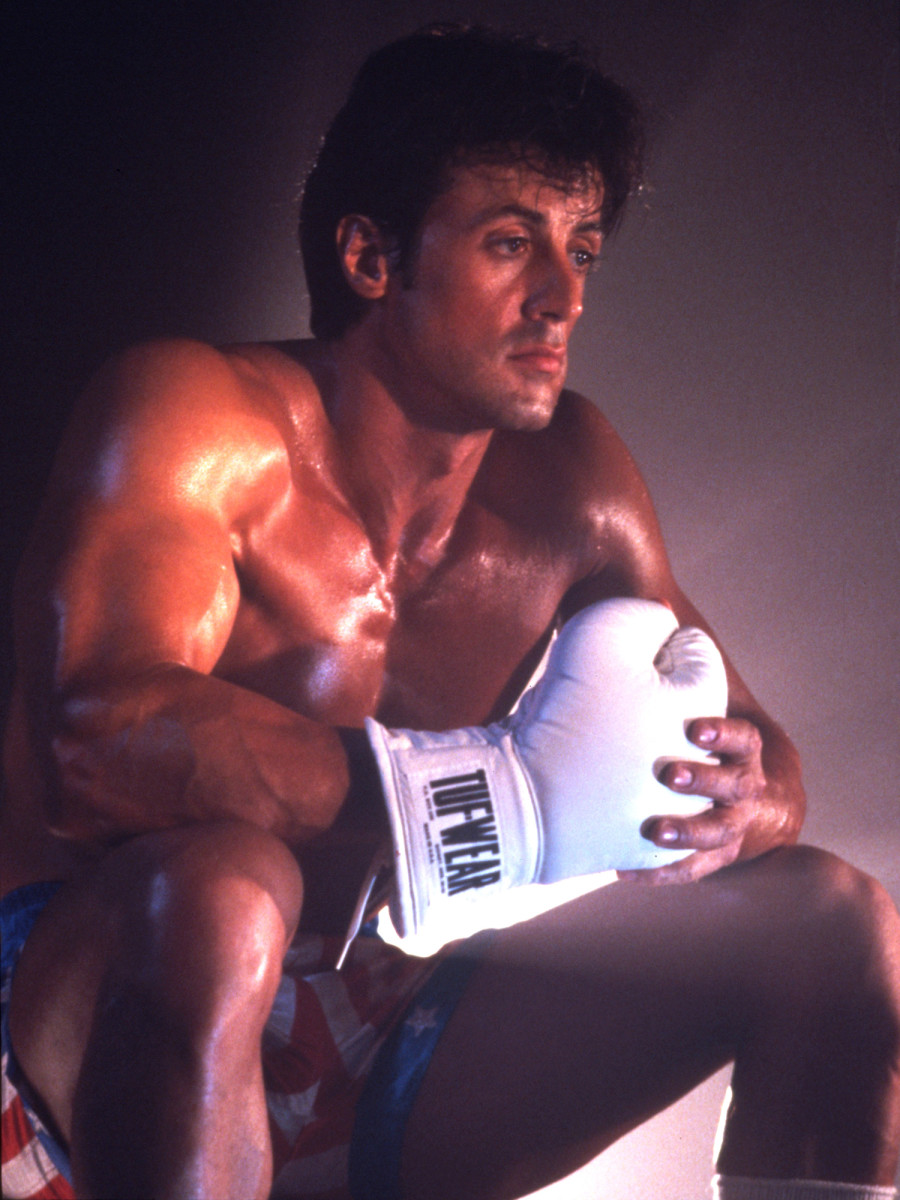

Adjusting for inflation, the seven previous films in the Rocky saga, before Creed II, ranked 14th all-time among franchises in terms of gross box office earnings. Among those 14, though, it is the outlier, the only sports-centric entry amidst the superheroes and the anthologies. And while, yes, all of these franchises claim passionate fan bases, none have had the profound, far-reaching impact of a series whose main character feels so true, so real that the man who plays its fictional protagonist, Sylvester Stallone, was inducted into the actual Boxing Hall of Fame in 2011.

“It’s not even fair to put Rocky in the world of just other movies,” says MGM president Jonathan Glickman. “He is a folk hero and he is an American archetype.”

Indeed. Rocky has been referenced in everything from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles to Pulp Fiction, from a Starbucks commercial to a Notorious B.I.G. song. It is the universal set—perhaps the only universal set—in the Venn diagram of Hilary Clinton and Donald Trump, that tiny sliver of overlap in their worlds, as each invoked the pugilist during a presidential campaign rally. It has even been reported that Kim Jong Un, the North Korean dictator, enjoys having the franchise theme song performed by large orchestras, as clips of Rocky IV play in the background.

For others, Rocky is a lifestyle. When Mike Kunda was eight, constantly bullied at school in Scranton, Pa., his grandfather gifted him a leather jacket and a black fedora, just like Stallone’s onscreen. Kunda became the character, wearing the outfit, repeating the lines, taking on his tormentors. Now 50, he hosts tours in Philadelphia, bringing fans to all the famous movie haunts—dressing, walking, talking just like Rocky.

The character tends to have that effect, turning the calculus of reality on its head. The more impossible the promise offered by the allegory of Rocky becomes, the more we want to believe it. The more people dedicate their lives to the franchise, the more they need it to be real, the more they gather in Philadelphia to visit the landmarks where the original Rocky was shot—places Rocky never really lived, but will always exist.

In Philadelphia alone there are two annual Rocky-themed races: Rocky Run, which brings in 14,000 participants hailing from 25 countries, and the Rocky 50K Fat Ass Race, which follows the 31-mile route that the titular character famously ran. There’s a third Rocky race, the Balboa Kör, but this one is 4,400 miles away, in Budapest. Every September, several hundred grey-sweat-suit-clad Hungarians run a 12-mile path through the Buda Hills, at an altitude of nearly 3,000 feet. The competition finishes at the steps of Geller Hill, the highest point in the city, a Hungarian homage to their hero.

Then there’s Zitiste, Serbia (population: 3,000). After suffering through decades of wars, disease and devastating floods, the citizens decided in 2011 to erect a statue to galvanize the town. A beacon of hope. They considered the Dalai Lama, Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. Instead, they chose Rocky Balboa.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Michael Vitez once spent a year in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, interviewing 1,000 of the franchise’s devotees, each of whom had re-created the first film’s most famous scene, in which Balboa runs the museum’s 72 stone steps. In Vitez’s 2006 book, Rocky Stories, he writes of a Frenchman with a Muslim father and Catholic mother, ostracized by both sides, who found a paternal figure in Rocky; of a groom who, on his way to his wedding, thought of no better way to prepare for marriage. . . . They came from all over the world, the author remembers, with their own journeys and their own reasons for running, but they all shared a belief in the transformative power of Rocky.

“There is no other movie like that, where you can bring the film to life,” Vitez says of how the character blurs the lines between fiction and reality. “There are men of a certain age that really believe Rocky IV ended the Cold War.”

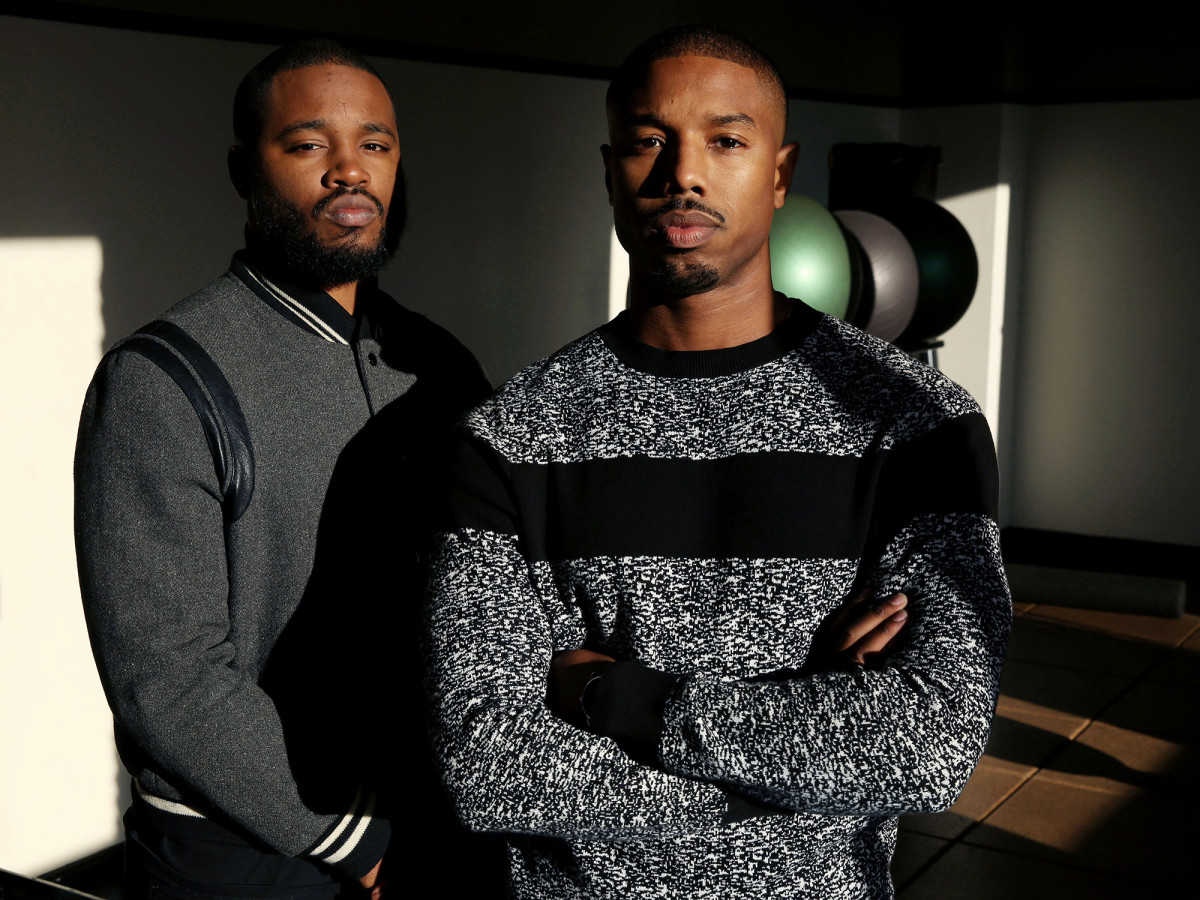

In 2012, Ryan Coogler, fresh out of film school at USC, finally managed to get a meeting with Sylvester Stallone after a year of trying. The 26-year-old’s pitch: Resurrect the Rocky franchise—and let me write and direct it.

In Stallone’s mind, the iconic character was retired. To the world, Stallone had himself become lost in Rocky over the decades. Never mind the fact that Stallone has written eight movie scripts, including one for which he received an Oscar nomination—he’s still viewed by many as borderline illiterate, as if he’s become Rocky. But whenever the actor has been wayward, he’s always returned to the character he knows best.

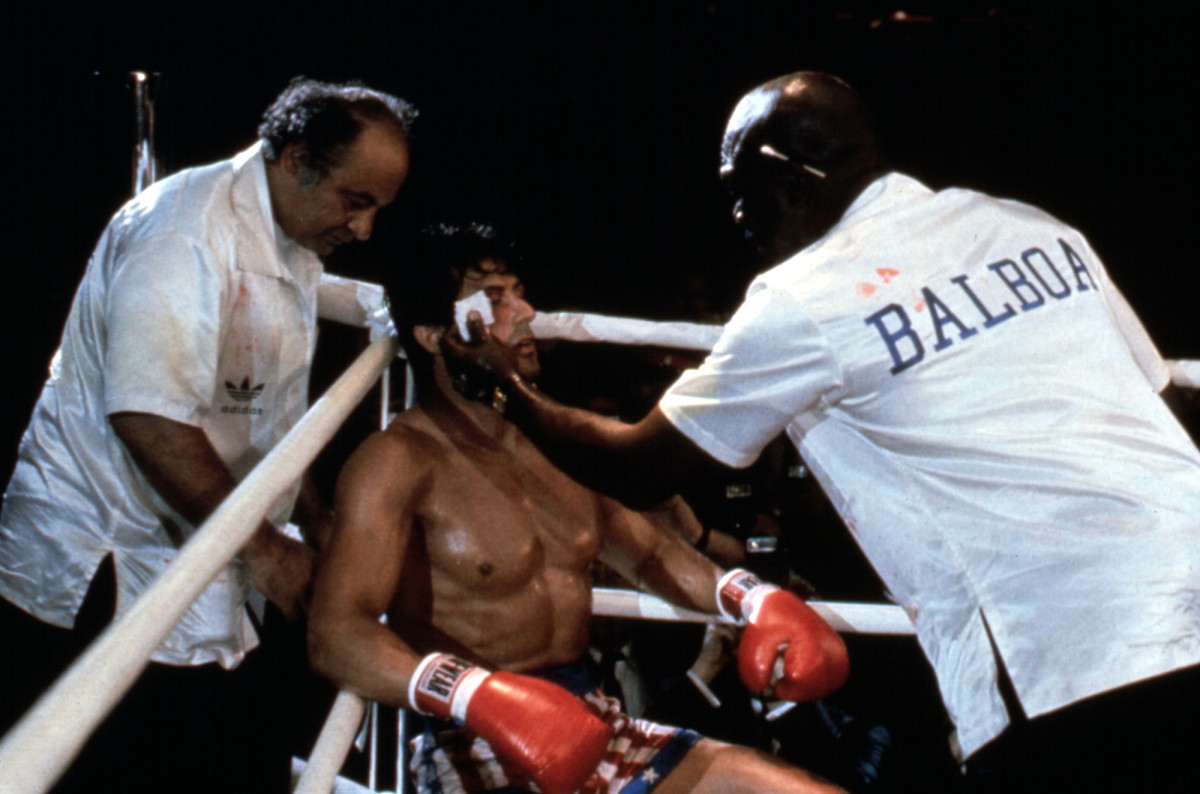

After Rocky V flopped in 1990, becoming the first of the films not to surpass its predecessor’s box office haul, thus derailing the franchise, it took Stallone 16 years to get a sixth movie made. His longtime producers believed their old audience had vanished, and for years Stallone struggled to find a studio that believed otherwise. That he eventually got a sixth installment, Rocky Balboa, onto the screen was an accomplishment. That it earned the best reviews of any Rocky movie since the original was nothing short of a Balboa-esque miracle. The film even served up a fitting end for the franchise: In the final scene Rocky waves goodbye, thanking his adoring crowd and, in reality, the movie’s audience.

Coogler was that audience. And now, sitting across from Stallone in the writer-director-actor’s home office, Coogler offered his own Rocky story. As a kid in California, he and his father, Ira, would always watch the movies together, and his dad would cheer and laugh—but mostly he’d cry. Ira would even cue up a favorite scene before Ryan’s football and basketball games, playing the part from Rocky II where the irascible trainer Mick (Burgess Meredith) goes into a hospital chapel and tries to rouse Rocky out of his funk.

Recently, Coogler told Stallone, Ira had fallen ill; a neuromuscular condition was robbing him of control of his skeletal muscles. Seeing his father dependent and withering, Coogler found himself confronted with the concept of masculinity. What makes you a man? What makes you strong? His dad used to take care of him. Now their roles were reversed. Isn’t time strange?

Coogler wanted to explore the relationship of fathers and sons, and he wanted to do so through his dad’s favorite character. His idea: Expand the Rocky universe, ensnare a new audience in the mythos by telling the story of Adonis Creed, the son of Apollo Creed, Rocky’s villain-turned-best-friend. It would be an underdog tale just like the original, but it would explore a new background, a new culture—the journey of a black man growing up without a father, but still living in his shadow. To do this, though, Coogler needed to bring back Rocky Balboa.

“No, kid,” Stallone responded. “I think we’re tampering with something we should leave alone.”

A year later, Coogler’s first feature-length film, Fruitvale Station, opened at the Sundance Film Festival to critical acclaim (with Jordan in the leading role). Stallone reconsidered their conversation, recalling the young director’s energy and passion, and changed his mind. The Coogler he met was sensitive and emotional; there was something authentic about him, something that reminded Stallone of himself, five decades ago.

By 1974, Stallone had made it to Hollywood, by way of New York, but he was struggling. After a few off-off-Broadway nude shows (Score) and some soft-core porn flicks (The Party at Kitty and Stud’s), he’d landed bit parts in more mainstream fare, always playing the role of the hardened street criminal: he mugged Woody Allen in Bananas and mugged Jack Lemmon in The Prisoner of Second Avenue. . . . He’d written millions of words in screenplays—one about a rock singer who couldn’t stop eating bananas—under a variety of pseudonyms: Q. Moonblood, W.G. Lake, J.J. Deadlock. . . . By ‘75, he had $106 in the bank, a pregnant wife at home, and an English mastiff that, legend has it, he had to sell outside at a 7-Eleven for $40 because he couldn’t afford dog food.

That’s the thing with the Rocky franchise: Even the verifiable facts behind the making of the movie have turned to myth over time. The exact details and chronology change depending on who is retelling the tale. What is clear, though, is that at some point, after being repeatedly typecast as a brute, Stallone decided he wanted to take that clichéd character and explore the soul of the person underneath. He kept coming back to the concept of unrealized dreams.

He had lunch with a producer, Gene Kirkwood, at the MGM commissary, and they spoke about Marlon Brando’s “I coulda been a contender” speech in On the Waterfront, about how audiences never actually saw Terry Malloy fight. Later—or possibly earlier, or potentially never—Stallone watched the 1975 Muhammad Ali–Chuck Wepner fight in a movie theater, and he was transfixed as the crowd cheered for the Bayonne Bleeder, who miraculously knocked down the world champ and nearly went the distance.

Stallone met two other producers, Irwin Winkler and Robert Chartoff, during an audition. On his way out of the room, after not getting the part, Stallone told the two men that he also dabbled in scriptwriting. He handed them one, Paradise Alley; they liked the writing, but it wasn’t right for them. So Stallone threw out another idea, about a club fighter who gets a shot at the title. His pitch: Let me write it on spec, no fee; but if you make the movie, you’ve gotta cast me. The producers agreed. Stallone finished the first draft of Rocky in 312 days.

It has become part of the franchise lore that Stallone turned down large sums of money to sell off the story—upwards of $360,000, again depending on the teller—because United Artists wanted James Caan or Robert Redford or Burt Reynolds or Ryan O’Neil to star. Which, Winkler says, is only partially true. Other studios attempted to buy the script from him and Chartoff with that plan, but they never planned to cast anyone else.

Really, so much of it was genius promotion, a means of capturing the audience’s attention. But as the years passed, and more and more Rocky movies came to parallel Stallone’s actual life, these tales became intertwined with the film—the behind-the-scenes story of the ultimate underdog, who wrote and starred in the ultimate underdog movie. A conflation of actor and character, fiction and reality.

Lesser told (and celebrated) is the story of that first draft of Stallone’s Rocky script, which was dark, cynical and angry. It would be unrecognizable to fans today. Mick was a virulent racist. Rocky threw the fight against Apollo Creed at the end. All of which was fitting of the anti-hero typical of that movie era. As film historian Jeanine Basinger, a trustee of the American Film Institute, points out, “the movies we were getting at that time were more violent, more discouraging.”

Basinger recalls, though, watching the final version of Rocky at a critic’s screening—typically quiet and unaffected affairs. And she remembers an audience that was clearly excited, enraptured. Their spirits were buoyed. That was different. “It was more like a real sporting event,” she says.

Frank Rich first saw Rocky in New York, in 1976, when he was the film critic for the Post. At the time, he expressed amazement: Normally-apathetic Manhattan moviegoers had left the theater “beaming and boisterous, as if they had won a door prize.” Rich, now a prominent political writer, views that as a sign of the times. “It had been an incredibly grim period in American life,” he says. “A bitterly divided country.”

Start in 1968. The assassinations of MLK and Bobby Kennedy, the riots in Chicago, the meltdown of America over the Vietnam War, the invasion of Cambodia, the Watergate scandal. . . . America was bitter, and its movies reflected that: “dyspeptic. . . dealing with corruption, disorder, decay,” says Rich. But by ’76, Watergate had passed, Vietnam had ended, and Jimmy Carter, an underdog peanut farmer, had captured the country’s fascination and been elected president. “The country was starting to heal. And Rocky really fit the mood.”

At his wife’s prompting, Stallone had rewritten his original script, transforming it into the Pollyannaish movie we now know and love. The final product was more reminiscent of the 1930s brand of movie optimism popularized by Frank Capra and known as Capra-corn. Basinger, the curator of Capra’s life’s work, says Rocky served as a “return to something more positive and hopeful,” and that’s partly the reason why it became such an overwhelming success in ’76.

Stallone gave audiences someone to believe in: the everyman, a self-described “ham-and-egger,” a guy who squandered his potential but still harbored big dreams. He convinced audiences that Rocky was relatable, believable, that—as he said in accepting his Oscar for Best Picture in 1977—there is a “Rocky in all of us.” The character inspired audiences that at the time were desperate for any sort of inspiration.

“People wanted this,” Basinger says. “They needed this.”

America in 1976, Rich notes, is eerily reminiscent of the country today. With a president who frequents in racially-charged discourse and in fomenting discord, the U.S. may be more divided, more in need of inspiration, than ever before. Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney notes that while the Rocky movies displayed a majority white population, reminiscent of the city in past eras, the two Creed movies showcase the current diversity of a metropolis whose white population has fallen by nearly a third since 1990. That’s more fitting, more powerful, more truthful in 2018. It’s what we need now.

“That inclusivity, that ability to generate pride in young kids of various colors and ethnic backgrounds,” says Kenney, “is really important for our own psyche as a country.”

In August 1986 a young comedian took to the stage at the Felt Forum in New York City wearing a purple-and-black-paisley leather jumpsuit and performed what would become one of the most beloved and culturally significant stand-up specials of all time, Eddie Murphy: Raw. Toward the end he joked about the Rocky movies and the hold they have on a certain audience. “White people, y’all go crazy after you see a Rocky movie because y’all believe that s---,” Murphy joked. “Stallone has y’all white people pumped.”

The Rocky movies are widely considered to be a universal movie franchise. The themes of grit and determination and overcoming improbable odds are relatable to all; race is rarely addressed in the franchise. But up until 2014, each and every Rocky movie was a white boxing movie, as most boxing movies are. The hero was white, as was the majority of the cast. That’s what Coogler set out to change.

Coogler knew the actor he wanted to lead this movement, in the role of Adonis, and he broached the idea with Jordan even before they began filming Fruitvale Station. Jordan didn’t have the same personal connection to the franchise as Coogler did—he’d only seen Rocky and Rocky IV at that point—but he immediately bought in. He understood the influence the Rocky character had on audiences, and he wanted to broaden the scope.

In 2010, SPORTS ILLUSTRATED ranked the 50 greatest fight films ever made; only two had black protagonists, and both of those—The Great White Hope and The Great White Hype—are self-conscious plays on the racial tropes inherent in the genre. In movies, even Rocky movies, black boxers are often portrayed as loud, brash and animalistic, mere impediments for the white hero to defeat. “We wanted to flip all those stereotypes,” says Jordan.

Adonis would be smart, focused, reserved. Coogler would showcase not just millennial love, but black millenial love. Tessa Thompson joined the cast to play Bianca, an emerging singer with degenerative hearing loss—a role she was attracted to because it brought fuller, more nuanced female characters into the Rocky universe. Adrian (played through five movies by Talia Shire) is an iconic character, Thompson points out, but she existed mostly as a pillar of strength for her husband, with no real dreams or aspirations of her own. That, too, would change.

“Things are changing,” Chris Rock said on the Dolby Theater stage as he opened the Oscars in February 2016. “We got a black Rocky this year. Some people call it Creed. I call it Black Rocky.”

A sequel was a fait accompli after Creed, released November 2015, earned rave reviews and hauled in $173.6 million worldwide. The movie introduced audiences to a new hero and a new love story. It also further proved that the old industry excuse was specious, at best: A movie with a black director and a majority black cast could have mainstream appeal. And here it helped launch Coogler’s and Jordan’s next massive success together, Black Panther, in 2018.

With Coogler staying on as an executive producer (but unable to direct because of time conflicts), Stallone wrote the basic outline for a sequel, Creed II. He was adamant that there needed to be a powerful villain, hence the return of Ivan Drago—the robotic Russian who killed Apollo Creed in Rocky IV with a vicious right hook—and the introduction of Drago’s son, Viktor, as the new challenger. Stallone was also set to direct the movie, but it didn’t take long for him to realize: Yes, Balboa and Adonis Creed lived in the same universe, but this was not Rocky. This was its own thing, speaking to a world Stallone knew he couldn’t.

So, on Coogler’s suggestion, the studio approached Steven Caple Jr.—a friend and former classmate of Coogler’s at USC who’d worked mostly in TV before breaking out with an indie, The Land, that explores inner-city poverty. Caple knows his movie history enough to lament that John Singleton never produced a Spike Lee movie in the same way that prominent white filmmakers collaborate with each other all the time. When the Creed job was finally offered, Caple, 30, first had to overcome his apprehension at taking on such an iconic franchise. But with the handoff from Coogler, Caple thought, Why can’t we be like George Lucas and Steven Spielberg? “Keep it in the family,” he says. “Cultivate the movement.”

Jordan, for his part, had decided long ago that he wanted only “white roles”—meaning, roles that were not written specifically for African-American actors. He didn’t want to star in films that dealt strictly with skin color. In Creed, the collective goal became to create a movie that didn’t have race built into the plot, but that was still black at its core. The same remained true in the sequel.

Caple worked with black screenwriters Cheo Hodari Coker (Luke Cage) and Juel Taylor on the story and the script, and he cribbed dialogue from moments in his own life, such as when he proposed to his wife, or when they were waiting on a pregnancy test in the bathroom. He added cursing and other offensive language into the script, including one use of the n-word, despite MGM’s trepidation, because that’s “how we talk to each other,” Caple says. “We just have moments where you feel the blackness, the black love, the black family. Those little moments are what make it yours, and what make it true to yourself.”

Caple pushed Jordan, too, to channel feelings from his own journey. The 31-year-old actor was being compared to Denzel Washington and Will Smith, and he felt overwhelmed and inadequate. He thought he had to create his own legacy—just like Adonis, Caple told him. Thompson, meanwhile, expressed worry about Bianca’s being pregnant in the movie and how that would affect her character’s ambitions. She didn’t want Bianca to end up barefoot, making Adonis sandwiches. Use that, Caple said, and the exact line ended up in the script.

Over the years, the story of Stallone’s steadfast refusal to sell Rocky to a studio that wouldn’t let him star in it became its own underdog tale, inspiring countless others. Matt Damon has often said there would be no Good Will Hunting without Rocky, because it encouraged him and Ben Affleck to write their own springboard roles. Creed will inevitably have a similar, more profound impact for directors of color, showing them that a minority filmmaker can helm a wildly successful studio film. Like Coogler, Caple was an unknown before he signed on to the Rocky franchise. Now he’s directed a movie that brought in $55.8 million in its first five days, the best ever Thanksgiving-weekend opening for a live-action film.

Creed II is more than worthy as a sequel, mixing some of the franchise’s most visceral boxing scenes with some of its most heart-wrenching dramatic moments. It also serves as a clear handoff of the franchise from Rocky to Adonis and, in effect, from Stallone to Jordan. (Stallone echoed as much in a recent Instagram post, saying, “This is probably my last rodeo. . . My story has been told.”) Everyone involved with Creed II, meanwhile, expresses a desire to make Creed III, Creed IV, Creed V. . . . Jordan hopes audiences become so invested in the Adonis character that they want to see what kind of man he becomes later in life, outside the ring. Just like with Rocky.

#www.instagram.com/p/Bquk06OharC/

As Caple worked on the script, Stallone told the director he didn’t want Rocky to die in this movie. Not yet. But the cast, the studio, the producers—they’re all preparing for a time when that happens, when the franchise goes on without the man who started it all. They feel, though, that they’re ready. There’s a scene near the end of the film in which Rocky sits in his chair outside the ring and lets Adonis soak in his moment, alone. “It’s your time,” Rocky tells his protégé, echoing the same line Stallone told Caple, Jordan and Thompson when they were filming.

“We are always trying to satisfy what the original pictures were about, but it’s moving in it’s own direction now,” says Thompson. “To me [that ending] was a really graceful way of saying, You’re with Creed now.”

Maybe there’s a real-life Rocky here, on North Front St., by the deserted red-brick building with the paint peeling off, the wood-boarded windows and the bolted-shut rolling door. Maybe it’s the guy operating the excavator in the construction zone next door, boring into the earth. Or the man trudging by with a paper bag half-concealing his Bud Light. Or the woman resting wearily on a nearby stoop, asking for change. Surely they all harbor dreams; surely each one could be Rocky.

There’s no sign on the building for Mighty Mick’s boxing gym, and there never was—not in real life. Nothing, even, that lets passersby know they’re standing in front of the gym where the bigscreen Rocky Balboa trained, where he was told he would eat lightning and crap thunder. To be fair, it never really was a gym; it was an old meat packing company when producers hung a prop sign outside, back in 1976—then it was a hardware store, then a mini-mart. Now it’s nothing, vacant like so many other buildings in the area. Just like Adrian’s pet shop, where Rocky courted his wife and bought his turtles, a few blocks down the road; that storefront was demolished last year. Around the corner, where Paulie drank Four Roses and Rocky dreamt about getting his one shot, Lucky Seven Tavern is now an empty lot.

Yet still they come to pay their respects. Every day, every week, every year, real people walk these streets looking for the ghosts of someone who never actually existed. Or who only exists inside of us, in those hidden places where we imagine ourselves overcoming tremendous odds to be reborn.

They come every week to the Laurel Hill Cemetery, though it’s rarely to see, say, the cenotaph for Alfred Reginald Allen, who died in France, September 1918, from wounds received. Or the monument for Major Levi Twiggs, the Marine who was captured during the War of 1812 and died 35 years later leading an assault during the Battle of Chapultec. No, far more often they trudge up the gravel road to Section L, where off to one side sit two tombstones, one reading PAULIE PENNINO; the other, ADRIAN BALBOA. When it came time to make the prop used in the sixth movie, in which it’s revealed that Rocky’s wife had passed away, producers originally went with Styrofoam headstones. But that, Stallone said, wasn’t good enough for his Adrian. She needed the real thing, granite like all the rest.

And so you can understand, then, how so many pilgrims end up at the cemetery’s gift shop, asking a simple question: Is Adrian really buried here? The workers behind the counter never know how to answer, because, for one, Who could they be talking about? The actress who played Adrian, who is still very much alive? Or the character herself, who is not real? The clerks always try to explain. But every week someone new comes and asks again, experiencing another breakdown of the line between myth and reality.

On the week that Creed II opens, the neighborhood where Rocky lived, where he trained, where he dreamed, is not a place where fairy tale stories seem to be incubating. Under the Kensington Bridge dozens of homeless people sit outside their tents, sharing cigarettes. Needles litter the ground. The smell of urine overwhelms.

Take a left on Somerset, right before the rehab center, and there it is. The steps are now painted black, and even that has largely peeled off. But that’s it: 1818 Tusculum St., the apartment where Rocky and Adrian would have spent their wedding night. If they had ever existed at all.