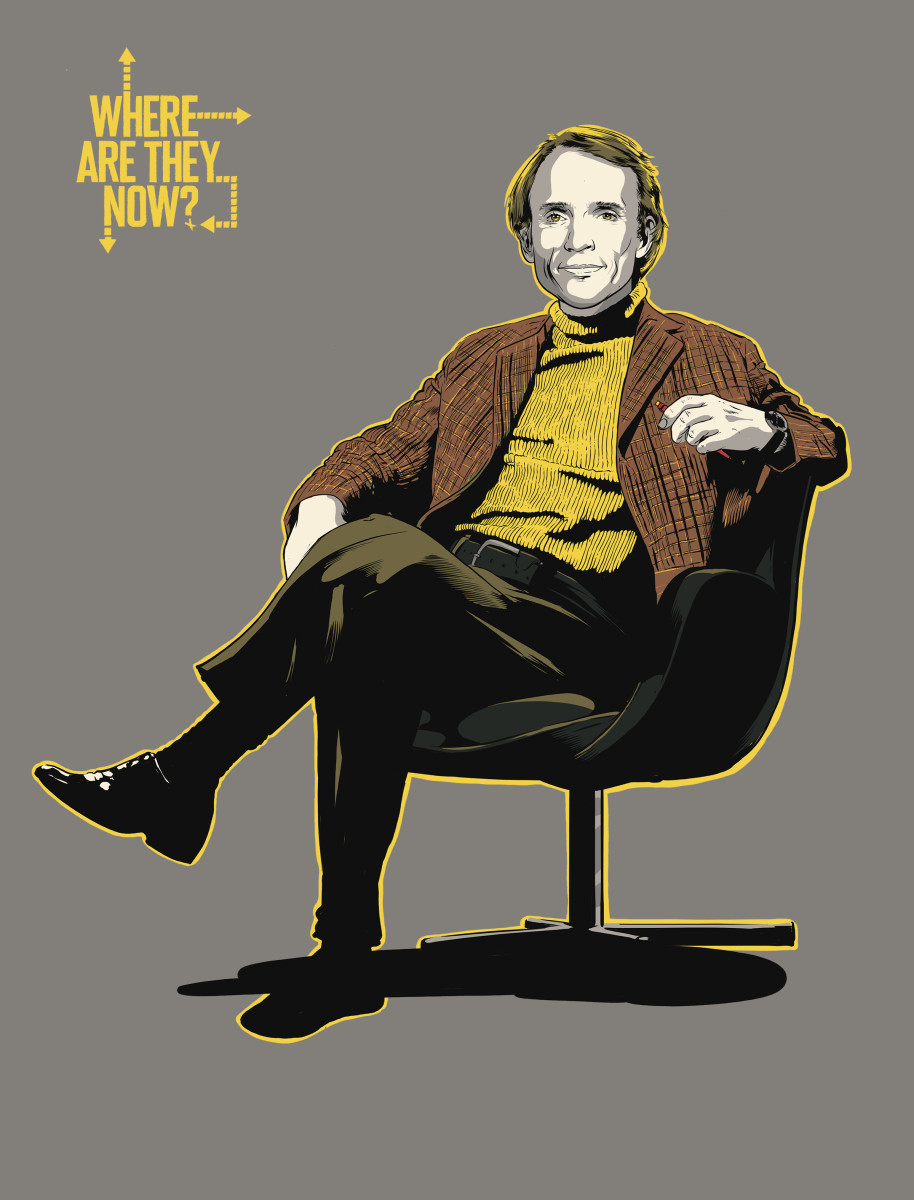

Dick Cavett: A Conversation Piece

Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. This year’s WHERE ARE THEY NOW? crop features a Flying Fish and a Captain, jet packs and NFTs, the Commerce Comet and the Say Hey Kid. Come back all week for more.

If, as The Washington Post’s tagline warns, “Democracy dies in darkness,” then how does civility perish? Is it slowly bludgeoned to death with a steady thump of hot takes? Does it get ratioed?

Is it hobbled when a blogger with the pet slogan “Don’t Be a Pussy” is handed the keys to Rush Limbaugh’s show, with its 16 million listeners? Poisoned when most every argument—on Twitter, or in the aisle of a Southwest Airlines flight—ends in a cage match? Stuffed in a locker by boorish fan behavior at NBA playoff games?

These days civilization sure seems a lot less ... civil.

“ ’Tis true, ’tis pity. And pity ’tis, ’tis true,” says 84-year-old Dick Cavett, America’s living monument to civil discourse. In case you don’t know the quote: “Hamlet. … No, Polonius!” he corrects himself. “Oh, no, now I’ve offended Shakespeare.”

Once upon a time, your home’s second TV was a black-and-white and America’s second late-night talk show host, after Johnny Carson, was Dick Cavett. From 1968 to ’75, ABC’s The Dick Cavett Show was an intrinsic part of the cultural—and countercultural—zeitgeist. Movie stars, rock stars, literary giants, political figures and, yes, athletes appeared on a set that was devoid of pabulum or self-promotion.

At the show’s zenith, Cavett had such immense gravitational pull that Joni Mitchell’s manager yanked her from appearing at a music festival in upstate New York for fear that she’d miss her appearance on his program. That festival? Woodstock.

“All of the other challengers to Carson were basically doing the same show, just not as well,” says Bob Costas, who was an adolescent when Cavett debuted. “Then you had Dick, who was doing something completely different. You come on Johnny Carson, and you have to perform. With Cavett, you had something else: conversation.”

Cavett, looking as if he’d escaped from a glee club, appeared equally at ease with Lennon (John) and Marx (Groucho). With Ali and Dali. With No. 7 (Mickey Mantle) and the Chicago 7. Cavett’s peak height was 5' 7", but he was never in over his head. “The secret was preparation,” says Robert Bader, a longtime friend and collaborator. “Dick was a quick study and he’s still a quick study.”

The Yale alum might have been elite, but he was not effete. Exuding an aura of “playful seriousness,” as author Clive James once put it, Cavett tight-roped between educated and endearing. “Once, as Muhammad Ali launched into a soliloquy of self-aggrandizement, Cavett cut him off. “You really get a kick out of yourself,” the host said. “Shaving must practically be an orgasm for you.”

Jocks were welcome at Elysee Theatre on West 58th Street in New York City, where the show taped, though sports were hardly an imperative topic. “We tried to book sports stars who had something colorful about them and didn’t just grunt and mutter,” says Cavett, who remains quite boyish, as octogenarians go. “In each case they recommended themselves as personalities.”

A Convocation of Conversation

On March 7, 1968, Elvis Presley recorded “A Little Less Conversation.” That same week, Cavett launched the program that would defy the maxim. And much more.

The premiere episode featured actress Angela Lansbury, writer Gore Vidal and the heavyweight champion of the world in exile, Ali. When the latter two got into an argument about Vietnam, a scant five weeks after the launch of the Tet offensive, it made for cracklin’ good television. The show, though, never aired. “The line I heard from one of the suits,” Cavett recalls, “was, ‘Nobody gives a s--- what Gore Vidal and Muhammad Ali think about Vietnam.’ ”

Viewers did, though. And Cavett maintained decorum, working his set, a rhetorical ring, like a scholarly but puckish Mills Lane. From the get-go, he understood innately that nobody was going to watch a talk show where people couldn’t speak their minds—and also that his guests had plenty to say. “I always would read [what] guests say afterward,” says Cavett, “that they’d never felt so comfortable on a talk show.”

Fortunately (and we’ll explain why later), most of the subsequent conversations and confrontations remain as near as your Wi-Fi connection. Cavett lives in Connecticut with his second wife, author Martha Rogers, but where he is absolutely flourishing—killing it, you might say—is on YouTube and other streaming services.

A sit-down with Ali from May 25, 1970, has received more than one million views. A clip from his Dec. 18, 1970, episode, featuring NFL all-timer Jim Brown and segregationist Georgia governor Lester Maddox discussing racism, has garnered more than 3.5 million views. A documentary film, Ali & Cavett: The Tale of the Tapes, won a Critics Choice Award last year and now lives on Hulu and HBO Max.

“People stop me all the time,” Cavett says, “and tell me, ‘I saw you last night with people who’ve been dead for decades.’ ”

The Only Living Boy in New York

“I never saw myself as an athlete,” says Cavett, who was born and raised in Nebraska. “But I was always agile. The best tree climber in the neighborhood.”

In 1950, Cavett enrolled at Lincoln (Neb.) High, where his father taught English. “My dad said, ‘It would be nice if you could letter in something.’ ” Natural selection precluded the nimble but undersized lad from earning an L in football or basketball, so he tailored his talents to a sport where he might excel: gymnastics. A few years later, Cavett became the state champion in the pommel horse.

The son of teachers, Cavett does not recall a time before he knew how to read. He may have been congenitally literate. “If a classmate read poorly in the second grade, I might have put my hands over my ears,” he says. “Ah, can’t be true—that would make me a dreadful person.”

After graduation from Yale in 1958, Cavett worked as a copy boy for Time magazine in midtown Manhattan. One day at the office, he read in the New York Journal-American that Tonight Show host Jack Paar “worries more about his monologue” than the rest of the program. So Cavett decamped to his apartment at West 89th Street and Columbus Avenue and pecked out a monologue.

In a condensed version of this oft-told tale of Cavett’s irrepressible ambition, he pressed the copy into Paar’s hands. Landed the gig. Had Cavett never gone on to host his own show, though, he still might have achieved TV immortality for one intro he wrote for Paar, however poorly it has aged. The guest was a starlet of the era, an actress famed largely for the size of her chest. Cavett wrote, and Paar proclaimed, “Here they are: Jayne Mansfield!”

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

That Cavett would go on to host a talk show, in various iterations on different channels for nearly three decades, is not mere serendipity. It seemed destiny for a son of the Midwest harboring a lifetime obsession with celebrity. Before he even left Nebraska he’d already met Johnny Carson, Bob Hope, Charles Laughton and Agnes Moorehead … just to name a few. He realized this obsession was peculiar. “There are only so many times you can tell your friends about the time you met Basil Rathbone,” he says.

The climax of this pursuit came at 24, when the newbie writer and talent scout on Paar’s Tonight Show met his childhood idol, Groucho Marx. “We met on the corner of 81st Street and 5th Avenue,” Cavett says, recalling the moment nearly 60 years to the day later. “During the Puerto Rican Day parade.”

Cavett had attended the funeral of playwright George S. Kaufman specifically to celebrity-gawk. It’s what he always did—years earlier he’d take the train from New Haven to Manhattan, a two-hour ride, just to case the bar where the mystery guests for What’s My Line? were stashed. (That’s how he met Buster Keaton.) At the service, Cavett spotted Julius H. Marx. Groucho. Trailed him outside, into the blazing sun. Finally, at the corner of 81st and 5th, he summoned the nerve to introduce himself.

“Groucho,” Cavett said, “I’m a big fan of yours.”

Groucho surveyed the young acolyte. “If it gets any hotter,” he answered, “I could use a big fan.”

Groucho would go on to appear seven times on Cavett’s program.

A Jock of All Trades

Guests came. And they came back. Among an endless parade of heavyweight champions—Joe Louis, Floyd Patterson, Joe Frazier, Mike Tyson, to name a few—Ali would appear 12 times on Cavett’s show, more than any other athlete. And no visit was boring. That’s because Cavett stood toe-to-toe with the Greatest and was a more-than-capable sparring partner in a battle of wits.

In one of Ali’s first appearances, an unassuming question by Cavett induced a two-minute harangue on the nature of “the white devil.” Cavett listened patiently, then began to reply when Ali cut him off and launched into more invective. Cavett finally looked him square in the eye and said calmly, “I’m going to talk for a second now.”

“I loved Ali,” says Cavett, who attended the boxer’s funeral, in 2016. “You could feel something palpable, powerful emanating from him. And he was very smart. Smarter than he liked to lead on.”

Ali and Howard Cosell may have established a more bombastic routine, but Ali and Cavett developed a genuine rapport. The heavyweight champ seemed to genuinely appreciate the acerbic wit of the benign-looking featherweight, as when Cavett introduced him by saying, “There are no great compliments I can pay my next guest that he hasn’t already paid himself.”

The Greatest kept returning to that theater on West 58th, not in spite of Cavett’s jabs but because of them. Ali endured enough sycophants in the course of a normal day. Here was this lily-white imp from silo country, bustin’ balls. Ali once told Cavett on-air, “You my main man.” And Cavett reciprocated with, “Remember when you used to be a loud-mouthed, bragging jackass?”

Ali smiled.

The friendship was genuine. In the early 1980s, Cavett invited Ali, after the two filmed a segment on Long Island’s East End, to stay at his house in Montauk. Cavett’s first wife, actress Carrie Nye (who passed away in 2006), was not home. Being the consummate host, Cavett put Ali up in the master bedroom.

Later, “my wife had a plaque placed over our bed noting that ‘Ali slept here,’ ” Cavett quipped. “There’s no plaque for me.”

Another time, Cavett visited Ali when he was in training, before the second Frazier fight. The Lincoln lightweight even entered the ring with the Greatest. In a memorable exchange, Cavett, in green silks, tossed a jab Ali’s way before pulling it back.

“You didn’t even flinch,” Cavett remarked.

Said Ali: “That’s cuz I know you ain’t crazy.”

For all the tales of fistic fancy that Cavett heard from the world’s top prizefighters, he never shared with them his own knockout story. It happened when Cavett was in the sixth grade. “I got in a fight with Herbert Largis—I hope he’s still alive,” says Cavett. “I got a hold around his neck, a move I’d learned from a judo book I found in the school library. He fell to the ground in a heap. He died, apparently. I moved back in horror.”

Herbert Largis did not actually die—otherwise, you might not be reading this story—but young Cavett had put him to sleep. “I taught that move to one person later in life,” says Cavett. “G. Gordon Liddy. He said, ‘I thank you for that.’ I don’t know if that lesson was the cause of anyone’s demise.”

Brown vs. Bored of Desegregation

“I liked to read my hate mail,” says Cavett.

A woman in Iowa once wrote: “Dear Dick Cavett, You little sawed-off, f--got Communist shrimp …”

Cavett recalls his response: “Dear Madam, I am not sawed-off.”

“I enjoyed ruffling feathers,” he says.

The Dec. 18, 1970, episode of Cavett featured a most unlikely trio of guests: author Truman Capote alongside the aforementioned NFL legend, Brown (then five years retired), and the Georgia governor, Maddox. Prior to entering politics, Maddox had owned a restaurant in downtown Atlanta, the Pickrick, where he steadfastly refused to serve Black patrons, in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. On the show, he and Brown sat side by side discussing segregation, the supposed gridiron brute exuding preternatural calm while the easily agitated governor became defensive. Cavett shrewdly remained silent. At one point, Brown turned to the host and asked, “Did you want to join this conversation?”

The tension simmered until Cavett erred. Brown asked the governor, “Do you have any problem from the white bigots because you [as governor] did so much for the Black man?” and the host repeated the question, substituting “bigots” with “admirers.” Maddox astutely admonished Cavett for the slight, and Cavett promptly admitted his error, telling the audience, “You know, he’s right about that.”

But Maddox was not satisfied. Instead of returning to the query of arguably the greatest player in NFL history, seated between them, clearly enjoying the awkwardness of the moment, the governor demanded an apology, threatening to walk off the set unless Cavett begged his pardon. Finally, Cavett delivered the mea culpa that rocked the world.

“If I called any of your admirers ‘bigots’ who are not bigots,” said Cavett, “I apologize.”

He was always agile.

Cavett Emptor: The Tale of the Tapes

Not long into his tenure as a TV host at ABC, Cavett inquired about repurposing a clip from an earlier broadcast. That episode, he was told, no longer existed. “ABC, in its finite wisdom, was taping over the show,” says Cavett. “Certain substances hit the fan. And it’s a shame.”

ABC was unwilling to pay for new tapes for every show, much less make space for a Cavett archive. This was not corporate skulduggery, just contemporary SOP: In 1967, both CBS and NBC aired the inaugural Super Bowl, yet neither network kept a recording of the contest.

While Cavett’s contract granted him ownership of the show’s intellectual property, ABC informed him that any tapes remained its own property. It was straight out of The Merchant of Venice: Take your pound of flesh, but no blood must be spilled. ABC was acting in the role of Shylock. … No, Balthazar! (Oh, no, now we’ve offended Shakespeare.)

In order to preserve his show, and its legacy, Cavett would need to start purchasing the tapes himself. He bought roughly half of the episodes that ran on ABC—approximately 400 of them—before he could ever know that VHS or DVDs or the internet would provide a platform for an extended shelf life. Maybe he understood he was compiling a priceless catalog of 20th-century cultural icons speaking their minds. Or perhaps he just wanted proof that he’d met Jackie Robinson and Orson Welles and Satchel Paige and Alfred Hitchcock. “These tapes have historic value,” says Cavett. “There will be people who won’t believe these people ever did television.”

Whatever the real reason, today the masters of all the extant tapes—2,500 or so, covering some three decades of Cavett’s shows—are now archived in the Library of Congress. No other late-night talk show host’s work is preserved there.

Fun With Dick and Jocks

Bobby Fischer, the U.S. chess prodigy whose personality could be generously described as erratic, was a regular on Cavett. Fischer appeared to enjoy himself, even when he was doing nothing more than teaching the host knight moves. “People would tell me I almost made him seem human,” Cavett says.

Time and again Cavett’s penchant for conversation, as opposed to an interview (a tip from his old boss Jack Paar), steered jocks and semijocks to a level of candor they had not envisioned while sitting in the green room. He asked Fischer what provided the visceral thrill in chess, and the famously guarded grandmaster answered, “Crushing the other guy’s ego.”

Cavett was a quick study and did his homework, reading any article he could find in an era before the Google search. A small item in a story he’d read led him to ask Mickey Mantle, out of the blue, if he was a bed-wetter. “I wet the bed until I was 16,” Mantle confirmed. Off-camera (right before Cavett cut to commercial with “Bed-wetters of all ages: We’ll be back after this short message”), fellow guest Paul Simon could be heard uttering in disbelief, “Mickey Mantle wet the bed.” It’s not, Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio? but it’s close.

As a host, Cavett, not unlike fellow Nebraska native Fred Astaire, was a seamless dancer who made his partners look good. “There’s this terrific myth I read about you before the Super Bowl game,” Cavett said to Joe Namath—“Mr. Joseph Namath”—in early 1969, “about you disappearing into a hotel with a lady and a bottle and being seen the next day wearing a fur coat.”

“Oh, no, no, no, that’s not true,” Namath objected. “I swear I did not have a fur coat on.”

The Rules of Civility

Five years ago, Cavett, along with his wife and his old friend Bader, attended Ali’s funeral in Louisville. Bader undertook the chore of securing their VIP credentials in a hotel lobby. When he told the clerk, “Three for Dick Cavett,” the woman behind him gasped.

“Oh, my God, Dick Cavett’s here?” she asked.

Bader assured her, he was.

“I’m Joe Frazier’s daughter,” said Jacqui Frazier-Lyde (whose dad died of liver cancer in 2011). “[Dick] was the only TV person who treated my father with dignity. I’d really like to meet him.”

When Bader introduced them, tears welled up in the old talk-show host’s eyes.

Cavett introduced himself to the American viewer during the most turbulent year of the 20th century. “These were very polarizing times,” says Costas. “You were either for the Vietnam War or against it. For civil rights or against it. For Nixon or against him.”

America was divided in 1968. America is divided now. The difference is that too often in 2021 the thoughtful voice is drowned out. How come an experiment such as The Dick Cavett Show worked then, in an age of three major networks, and is nowhere to be seen today? Costas, whom Cavett has referred to as “my illegitimate son,” is returning to HBO with a not-dissimilar format called Back on the Record—but it’s unlikely you’ll see Tom Brady or Steph Curry veer too far out of their respective lanes in a live format like Cavett’s.

“Now, athletes have social media accounts, a zillion handlers, a zillion dollars, many ‘interviewers’ more than willing to toss softballs in return for access,” says Costas. “They’re less willing to subject themselves to fair but pertinent questions. Doesn't make it impossible. But a credible—even prestigious—platform and credible host/interviewer is no longer a guarantee of a [guest coming on your show].” In other words: Why expose your views to someone else's microscope when you can just peck out your message on The Players' Tribune?

Cavett has spent the past year assisting Bader on an American Masters documentary, Groucho & Cavett, that will air on PBS in 2022. The pandemic wrought a surfeit of Zoom memorials to attend and, as his wife, Martha, attests, “more fan letters than usual from people with extra time on their hands.” He tracks current events and cable news, and he finds it all somewhat dispiriting.

“In a way, I really couldn’t imagine doing my show today,” says Cavett, even though he is as mentally spry as ever. “Too many villains as well as heroes now.”

It is telling that when offered the chance to opine on the current coarseness in American discourse, Cavett deflects by quoting Shakespeare. And then apologizes to the Bard for misattributing the quote. A scholar and a gentleman to the end.

“The Dick Cavett Show can’t happen anymore, and there’s a simple reason for that,” says Bader. “Because there isn’t another Dick Cavett.”

More Where Are They Now? Stories:

• The Charmed Season: Revisiting Derek Jeter’s Origin Story

• Pete Sampras Is Doing Just Fine