Coming Down From The Mountain

Strength comes in many forms and has many sources. But what does it mean to be strong? We have a few ideas. Check back throughout the week for more.

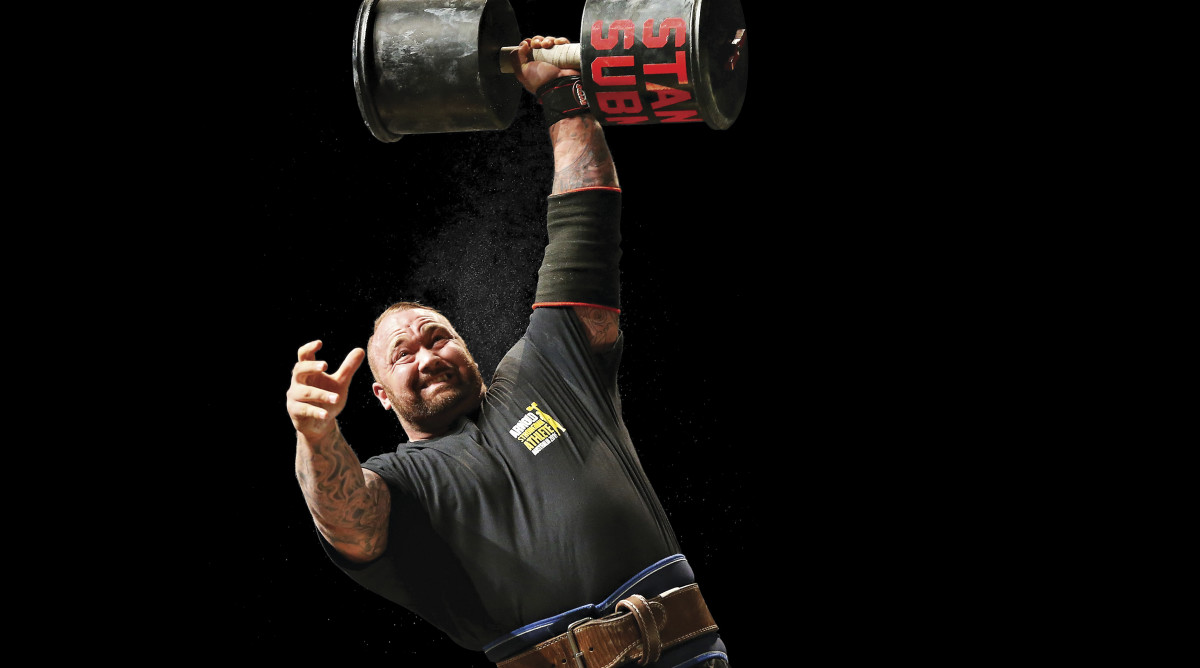

The Mountain is a bluff. Biceps that were once cartoonish, the circumference of another man’s waist, are now merely . . . large. A belly that looked like a minibar grafted onto a torso has gone from convex to flat. What once were masses of muscle now are sinewy vines, laced with rivulets of veins. This must have been what it was like to see Samson lose his brute strength. Only this transformation is by choice. This is a story of loss—but, ultimately, of gain.

In 2018, Hafþór (pronounced half-thor) Júlíus Björnsson was playing fearsome Gregor Clegane, The Mountain, on Game of Thrones. Björnsson is from Iceland but also straight out of Norse mythology, a Leviathan whose character once crushed a man’s skull with his bare hands. That same year, Björnsson was, literally, the World’s Strongest Man, winning the made-for-television competition. Over a weekend in the Philippines, Thor, as everyone predictably calls Björnsson, flung kegs, tugged buses and lifted cars farther, faster and higher than any other contestant in the international field of Goliaths.

He was 29 then and weighed somewhere north of 425 pounds. Who knows, exactly. As he puts it with characteristic candor: “When you’re that big, you can lose a few pounds just by [going to the bathroom].” And today? As Thor often does, he fires up his calculator app to convert kilograms to pounds. He concludes that since his peak he has lost 130 pounds. Easily. Or, he says in his resonant baritone, rumbling laugh, “one wife.”

He’s 33 now. The last time he was this size? He was 10.

In order to best explain how Thor molted the equivalent of another human being as if it were snakeskin, it’s probably worth explaining how he became so damn big and strong in the first place.

Growing up outside of Reykjavík, he braced for being tall, if not strong. Thor’s father, Björn—hence the surname Björnsson, per Icelandic naming tradition—today stands around 6' 8". Thor played basketball, and as he grew he got better. By the time he was a teenager he was 6' 9", shaped like the ice floes drifting in the harbor. He made the U-18 national team and had designs of playing in a professional league, which he might have, if not for nagging ankle injuries. During one rehab stint he began lifting weights, and it fed something in him. Soon he quit basketball and committed to becoming a competitive strongman.

What exactly did strength represent to young Thor? He strokes his beard before landing here: “I just really enjoyed being strong because I felt good about myself. You look around and say, I can lift more weights than anyone in the entire gym. You basically become hooked. You see your body change, and that’s addicting, too.”

To keep adding mass, his relationship with food became another contest. He didn’t merely eat. He destroyed plates. His daily meal count: eight. His daily calorie intake: 10,000. He would eat to the point of feeling nauseated, and sometimes beyond.

Thor’s secret weapon: “rice with dextrose and butter.” Another hack: “Take rib eye steaks and make them into patties. But you eat six steaks a day and your jaw gets sore. Instead, I [make what I call] ‘monster mash’: rice, dextrose, butter, minced beef—the rib eye—in chicken stock and mix it together. Tastes like sausage.”

Especially in Iceland—a country where, fish and licorice notwithstanding, most foods need importing—his grocery bill traced the same arc as his girth. But a weightlifter working security gigs at banks doesn’t have $5,000 a month to spend on his diet. “I was borrowing from everybody just to eat,” he says. Clothing made for another expense. Eventually he found a tailor across the Atlantic, in the Twin Cities, who specialized in habiliment for men who weighed as much as a piano. (Yet another expense: pharmaceuticals. In past interviews, though not this one, Björnsson, who never failed a test in competition, has admitted to using steroids. He declined, too, to address with Sports Illustrated an ex-girlfriend’s allegation of domestic violence; a police investigation found no grounds for action, and Björnsson has denied wrongdoing.)

Apart from adding mass and brute strength, Thor worked on technique. Yes, there are best practices, not just for deadlifting but also for hauling school buses and anchors and the like. In 2010 he won the Strongest Man in Iceland event, not to be confused with Iceland’s Strongest Man, which he won the following year.

Like most competitive lifters, Björnsson eventually focused his efforts on winning the World’s Strongest Man, a contest in which Iceland has often punched—plated?—above its weight. This island with a population of 350,000 won eight times in 12 years across the 1980s and ’90s, riding the lats of Jón Páll Sigmarsson (’84, ’86, ’88, ’90) and Magnús Ver Magnússon (’91, ’94 through ’96). Cultural anthropologists can debate whether those wins are simply the legacy of Viking settlers 1,200 years ago or whether strength contests become the main competitive outlet when you’re stuck on an island. But, says Björnsson: “Being strong, it means a lot here. Lots of alpha males.”

He looks back and laughs at his central tension: “Basically, I lived the life of a perfect athlete. My entire life was about how to get better. How to recover better. How to have a better diet. I never partied. Never drank alcohol or used any [recreational] drugs. The only things I relied on were the things that could make me better.”

But, he adds, “Better just meant stronger.” Everything was in service of strength for strength’s sake. Fearful of losing the weight he put on, his cardio was limited to 10 minutes or so of walking each day. And that was mostly to stimulate his appetite.

Between his lifting and his diet, he packed on as many as 80 pounds in a single year—and it was never enough. “Big-rexia is a real thing,” he says of the distorted body image he once had. “If you’re 400 pounds, you look at yourself in the mirror and you think, You’re not big.”

Read More From SI’s Strength Issue

In 2011, Björnsson competed in his first World’s Strongest Man contest, in Wingate, N.C. Two years later, HBO scouts, while filming in Iceland, emailed and called him. As a test, they had him lift a man above his head and wield a prop sword—and, Thor says, he was pretty much signed right there to play the hired muscle to the big bad on Game of Thrones.

He was now a demi-celebrity in two cult subcultures. “I was getting all these calls, ‘Can you come to our Renaissance fair?’ It was wild,” he says. By this point, he had no problem repaying his grocery loans.

Moonlighting as HBO’s most-hated hulk presented challenges to Björnsson’s athletic routine—but it may have been a disguised blessing. When he wasn’t teaching the GoT cast and creators how to deadlift, he had to go to lengths to get in his workouts. He also had to listen to his body. Shooting in Belfast and Croatia and in the guts of Spain, he didn’t always have access to gyms. After long shooting days, he figured his time was better spent resting than lifting. “I just had to make it work and stay competitive.”

He did. And he more than did. After various second- and third-place finishes, Björnsson won the 2018 World’s Strongest Man competition on account of his dominant performances in the car dead lift, the overhead press and the loading race (in which he lugged an anchor, an anvil, a keg, a safe and a 330-pound sack).

It was around that time that GoT wrapped up its eight-season arc. Björnsson was 29. Time for a career change. Time to stop walking around at 450 pounds.

Back in Iceland, Björnsson opened Thor’s Power Gym, an unprepossessing joint in a strip mall, a few miles from Reykjavík’s downtown. Icelanders come in year-round to bulk up and firm up. Björn—whose face adorns an employee-of-the-month placard—works there. Thor’s mother and sister pop in to work shifts as well.

As for his own shape-shifting, Björnsson turned to boxing. In some respects, it was strongman-adjacent. “You set a goal. You work on technique,” he says. In other ways, it presents a completely different set of challenges and dynamics.

Björnsson doesn’t just have to, as he says, “fight the mountain”—meaning himself, his physical and mental limitations. Now he has a designated opponent. “The other guy is there, and you’re fighting him, looking him in the eye, for 18 minutes straight.”

But he took to it, hooking up with a trainer, watching videos of himself sparring, learning the sport’s nuances and hacks. Now, the lug who once walked 10 minutes just to stimulate his appetite goes for 50-minute jogs on the treadmill or sessions on the bike. He even has abs. “It’s like I’m back in basketball shape,” he says.

As the weight has melted off, Thor’s grocery bills have gone down. He’s also had to summon that Minnesota tailor to take in his suits. The new body “took some getting used to,” he says, “but I like it. I’m getting a six-pack, man!” Asked whether he still feels like the strongest man in the world, Björnsson pauses. “I know I’m not. But I feel powerful. More here,” he says pointing to his head. “It’s strength, but in a different way.”

His first professional fight, an exhibition in Dubai in January 2021 against Steven Ward, ended in a draw. As did his next, against Simon Vallily of England. Last September, though, Björnsson took on Devon “No Limits” Larratt, one of the great arm wrestlers of all time (after another opponent withdrew), and Thor won his first real fight by TKO. In March he had his biggest fight, against Eddie Hall, a rival from the world of World’s Strongest Men. And here he had extra fuel. Says Thor, “I’m telling you: I. Do. Not. Like. Him.”

Two well-known athletes, now in a new arena, filled the actual arena, the Dubai Duty Free Tennis Stadium. But when the bell rang, they looked like two men competing in different sports. One was merely strong. The other was strong and precise. Hall, at 313 pounds, still looked like a strongman. Björnsson had transformed his physique—and in the end he won a unanimous decision. (His next opponent, as of this writing, is likely to be Martyn Ford, a former bodybuilder who’s known as the World’s Scariest Man.)

Björnsson is realistic about boxing. He’s not exactly calling out Tyson Fury, quick as he is to admit that, as a late starter, he remains a work in progress. Which is fine. “Same as in [weightlifting],” he says, “you just try to be disciplined and committed and get a little better each day.”

After the Hall fight, Björnsson returned home, relieving his wife of childcare. Their son, Stormur Magni Hafþórsson, is 20 months old. If nature and/or nurture do their thing, Iceland will have another mountain, another pillar of strength. Or maybe not.

“You know what I’d love for him to do?” Thor asks. “Gymnastics. Our traditional sports in Iceland, they are about toughening you up. But gymnastics? That’s the sport to start out in. Strength is one thing, but we’re talking agility. That’s the foundation.”

• ‘Oh, You Look Like The Rock’: Finding Rocky’s Family

• Kelly Slater Won the Super Bowl of Surfing at 50. So, What’s Next?

• NBA Draft? Nah. He’s Following the Money, Right Back to School.