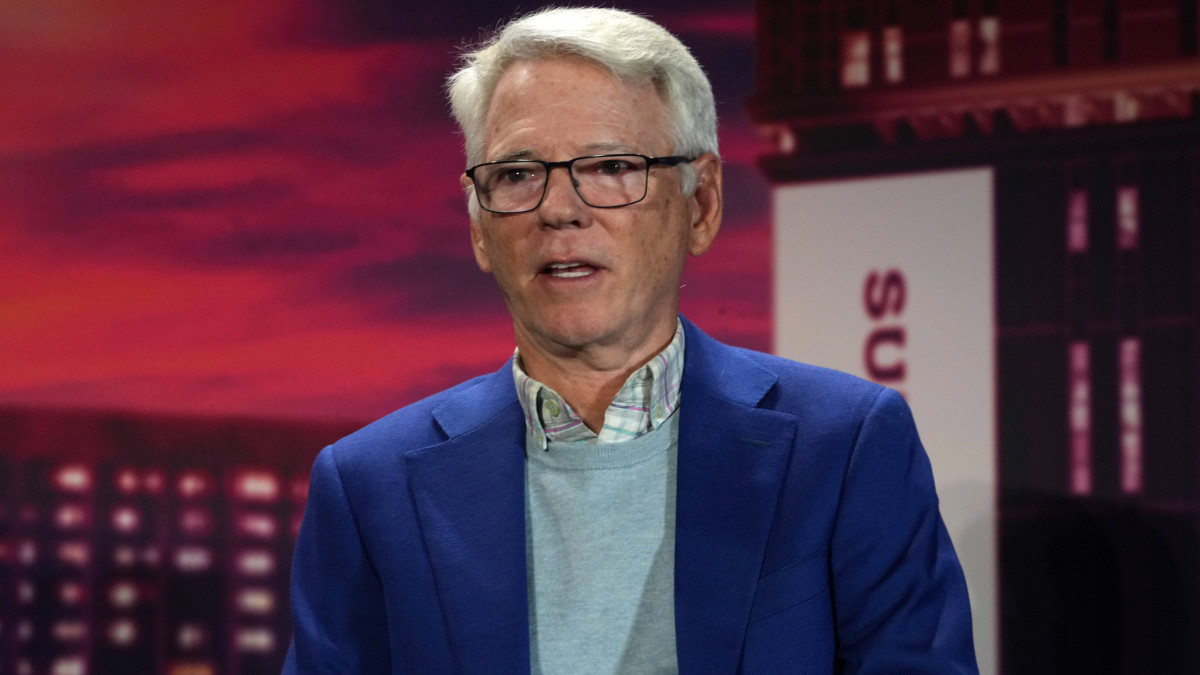

Sean McManus on His CBS Sports Tenure and What’s Next for Sports Television

Sean McManus is the son of broadcasting legend Jim McKay … yet “at around age nine,” he decided that, while he wanted to work in the industry, he didn’t want to follow his father and appear on camera. McManus would start as a production assistant at ABC Sports, working for scorched-earth producers like Don Ohlmeyer (a heroic smoker and curser) and Chet Forte (a heroic gambler) … but McManus was known to raise neither his voice nor his glass.

Charting his course, McManus—quietly, measuredly, dignifiedly—became one of the titans of sports television. In 1996, he was named president of CBS Sports, which had just lost its NFL broadcast rights. Then, as now, a network sports division without professional football is akin to a sports bar without an operational beer tap. But McManus used his methodical and low-key approach to win back a late Sunday afternoon NFL package which, without exaggeration, may have saved the entire network.

For the next quarter century, CBS Sports would acquire additional rights and lose others. It would get out of the Olympics business; it would sell off the SEC; it would pick up the Big Ten and soccer; it would continue as the primary home to March Madness. All the while, CBS Sports would take on the identity of its understated, decorous president. This, not by accident, is the network of Jim Nantz, Ian Eagle and Tracy Wolfson; not Stephen A. Smith, Skip Bayless and Pat McAfee. (Full disclosure: I work as a member of the CBS news division.)

In November, McManus announced that after nearly 30 years—an inconceivably long run in the modern TV landscape—he was handing the job over to his longtime lieutenant, David Berson. In his season finale, as it were, he will oversee February’s Super Bowl LVIII, the Final Four in March and the Masters in April. Then, he’ll leave the truck to work on his own golf game.

Sports Illustrated recently visited McManus at his sprawling corner office on 57th Street in Manhattan, where his desk is flanked by large prints of Duke basketball (he is a class of 1977 alum), Tiger Woods and Patrick Mahomes. His equivalent of an exit interview, the following has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Jon Wertheim: If you were an athlete, I’d ask: What was your biggest win, and your most stinging defeat?

Sean McManus: I would say the biggest win was bringing the NFL back to CBS. The corporation really felt the sting of losing the NFL in all-day parts. Not just in sports, but we went from being No. 1 to being No. 3 in prime time. It was a long shot. Nobody thought we were going to be able to do it. We were able to do it with a really good team effort including the hierarchy at CBS.

I would say the biggest defeat was not renewing U.S. Open tennis. In retrospect, I wish we had figured out a way to do that because it was a signature property. Listen, we did it for all the right business reasons. But if I had one back, I think that would be it.

JW: What does a cable bundle look like without the NFL?

SM: Really, really challenged. In many ways, sports—and the NFL specifically—is keeping the cable bundle together. It’s by far the most valuable content right now with respect to distribution. The viewership for the NFL is almost hard to believe. In a world where eight million people watching a prime-time show is an enormous runaway hit, we’re averaging over 20 million viewers for a 4:25 [p.m.] game. And it’s true on CBS, NBC, Fox, ESPN, even Amazon now. There’s nothing like it. Of the top hundred most-watched programs [in 2022], 82 were NFL games.

JW: When you were coming into this business, you perhaps didn’t anticipate the [NFL preseason] Hall of Fame Game would outdraw MLB playoff games, right?

SM: Right.

JW: How do you explain it?

SM: The ultimate television sport. It has all the visual appeal; 22 gladiators competing and putting their bodies on the line on every single play. It’s incredibly vibrant in terms of the players and their uniforms. And it’s a 12-month-a-year franchise now.

Every game is important. I love hockey and basketball and baseball, but you really can't make the argument that every single regular-season game is critical. You can really make that argument in the NFL with 17 games. And the fan base in these communities is amazing. … Also, listen, there is an element of violence and risk, which I think adds an importance to the actual game itself; the risks that these players are willing to take and the skill level—when you see a wide receiver tap his two toes down an inch, into the playing field while trying to catch a football—and the way that is captured ... it's just a visual feast for the eyes that lasts three hours.

JW: What’s the biggest innovation in the truck in the last 30 years?

SM: I would say, high definition and super slow motion capability. The action has always been very appealing, but it’s so vibrant now and crystal clear.

JW: Do you have a favorite athlete?

SM: I have a lot of favorite athletes, but I would say the one that has had the most impact on me has been Tiger Woods. The first Masters I ever did was in 1997. And what he did—not just from a golfing standpoint, but from a historical standpoint, a social standpoint—was so enormous. I walked out of that truck feeling that we had documented history. Which we did.

Then when he came back and won in 2019 after 11 years since his last [major]. It's like a pitcher throwing a perfect game in Game 7, then going through all sorts of personal and physical issues, extreme issues, and then coming back 11 years after that, throwing a perfect game in Game 7. I don't think that's an exaggeration. When you look at what Tiger went through, a lot of self-inflicted wounds—which he has owned up to—the physical [wounds], I mean if he had just gone away and had never done anything else, he still would have been the greatest of all time. But he came back and did something.

The other one I would say is Tom Brady. When we got the NFL back, our timing turned out to be great because we had the AFC. And we had Brady and we had [Peyton] Manning. Following the historic accomplishments of the New England Patriots and Tom Brady we got spoiled.

JW: You probably get asked plenty about your dad. Tell me something about your mom.

SM: She kept our family together. My dad was away 45 weekends, 47 weekends a year. She realized that if he was going to be successful, he couldn’t worry about anything that was happening at home. That, when he went away, he had to be secure in the knowledge that his wife was running the show really well—whether it was to drive my sister or me to our sporting events or making sure we were doing our homework and being raised in the way that both my mother and father thought we should be raised.

She wrote every single check. She balanced the budget. She organized the holidays. I don’t want to diminish my father’s role in raising us because he was a very, very involved father. But he had a full-time job that meant he was away most weekends. We had a skiing house in Vermont. She would load the car up Friday afternoon with my sister and me and our friends, drive three and a half hours to Woodstock, Vermont, take us skiing and get back in the car at four o’clock Sunday afternoon in the dark and drive us home. When Dad was in Monte Carlo or Yugoslavia. But I will also say that growing up the son of Jim McKay was a pretty amazing experience to go to events with him, to watch him on television every weekend.

JW: What will you miss most?

SM: I just like the fact that we get to produce some of the greatest sporting events in the world. Being involved in a live televised sporting event is the closest thing to being an athlete with respect to preparation. Second by second, hundreds of decisions that you have to make. You can't make a mistake without everybody knowing about it. True of athletics and true of television production: teamwork. Everybody from the tape operator to the audio man, to the announcer, to the producer, to the graphics coordinator, everybody has to be totally in sync for more than three hours.

And then when the event is over and you’re done—when you believe you’ve done the best job that you possibly can—it’s excitement and exhilaration and high fives and hugs. It’s like being on a team that just won the Super Bowl. It’s really euphoria in that moment. After the green jacket ceremony, I imagine the winner of the Masters is with his family and his coach and his agent, and they’re all hugging each other. We’re doing the same thing in the production truck. We really are. And that’s, that’s what I will miss the most.

JW: Last question: want to join this parlor game that we all play? Where is this crazy sector going?

SM: I think it’s still a healthy business. All of our properties now are working very well for us. They’re contributing to the success of Paramount—not just CBS but Paramount. The sales, in a very tough marketplace, are very robust right now.

The television ratings, generally speaking, are really substantial for sports television. So I feel good about the industry going forward. I’m speaking really of a five-year window. If anybody tells you what’s going to happen beyond five years, I think they’re probably not telling the truth because I don’t think anybody knows. The overall [media] industry is challenged and more and more people are consuming media in different ways. But I feel good about the sports television business.