Baseball's All-Scandal Team

Baseball's All-Scandal Team

Mark McGwire

His aura from the Maris mark-shattering summer of '98 and surefire Hall of Famer status vanished in a cloud of suspicion as the lid came off baseball's steroid era. The towering slugger admitted to (legally) using Andro during the Great Home Run Chase, but refused to discuss whether he used steroids at a congressional hearing in 2005, and then assumed a public profile that's been slightly lower than a CIA spook.

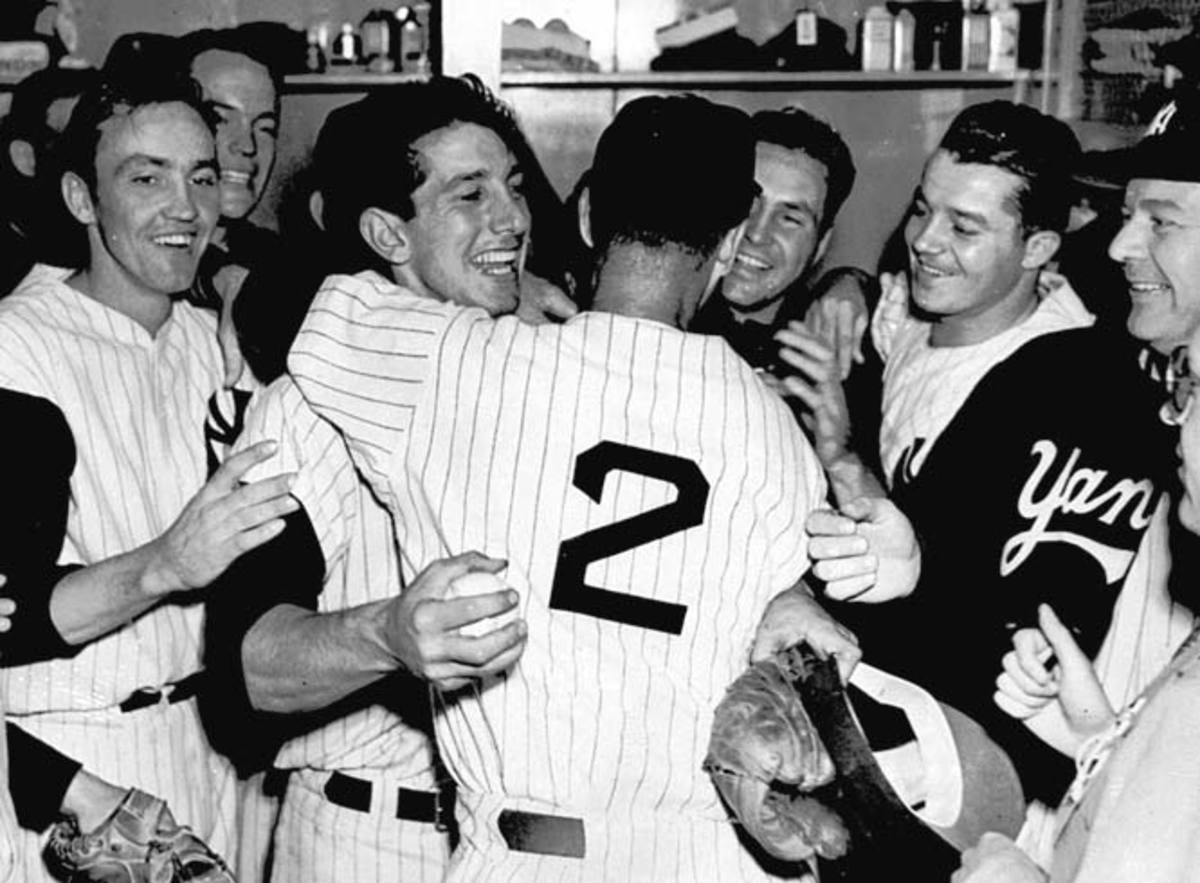

Billy Martin

Before he was a brawling, hard-drinking manager (five tenures as George Steinbrenner's skipper/sparring partner), he was the scrappy favorite of Yankees manager Casey Stengel and the '53 World Series MVP. Alas, he was sent packing in 1957 after the infamous Copacabana nightclub donnybrook that included carousing partners Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford.

Miguel Tejada

With the feds snooping into his possible lying about steroid use (he was mentioned 38 times in the Mitchell Report), the four-time All-Star was presented with a birth certificate that stated he was actually two years older than he told the Oakland A's when he signed with them in 1993. Tejada, 33 not 31, 'fessed up to the fib, saying he was only doing everything he could to escape a life of poverty in the Dominican Republic.

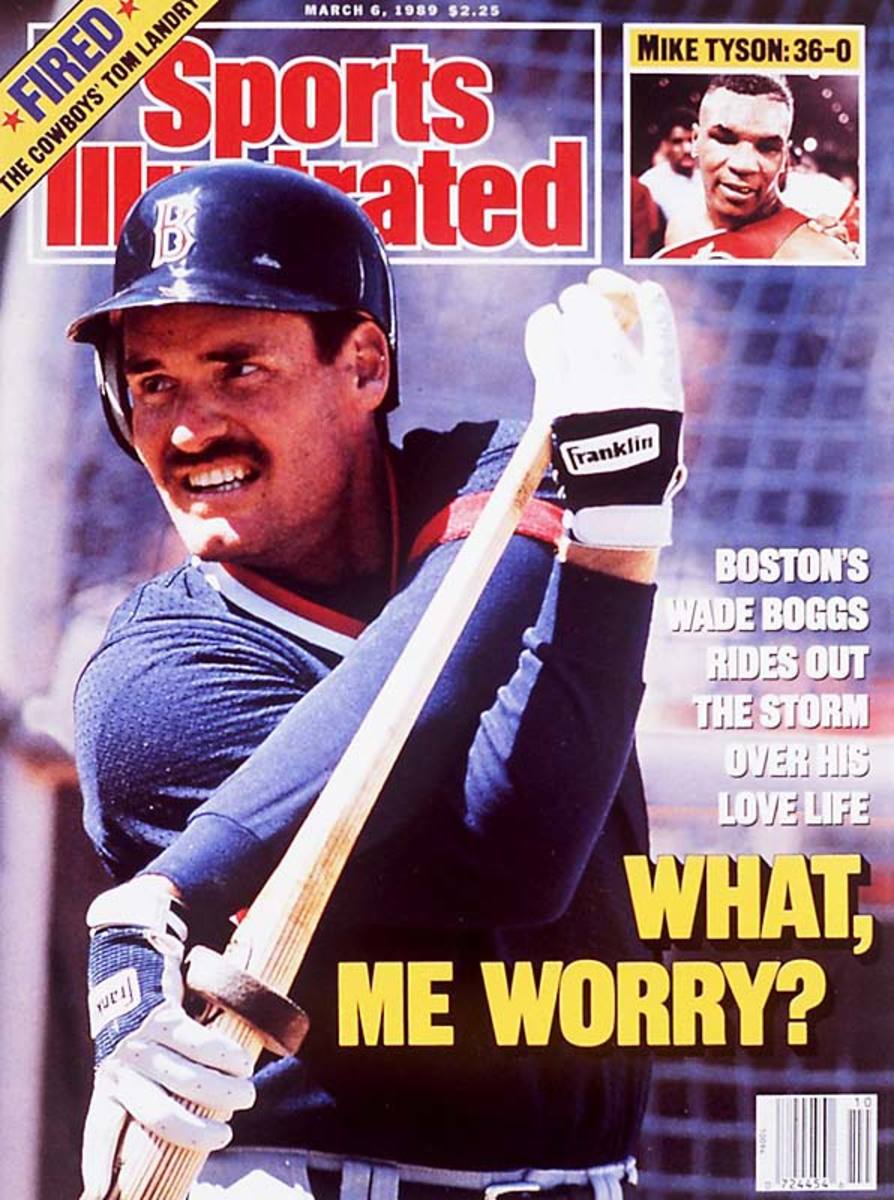

Wade Boggs

Boston's five-time batting champ became the face of extramarital canoodling when it was revealed in 1988 that he'd been singing "Why Don't We Do It On The Road" with mistress Margo Adams for four years. When Boggs cut ties, Adams sued him for $12 million worth of emotional distress, and dished sauce to Penthouse. With fans chanting "Mar-go!", Boggs came clean by going on 20/20 to tell Barbara Walters what a mean old conniving blackmailer Adams was.

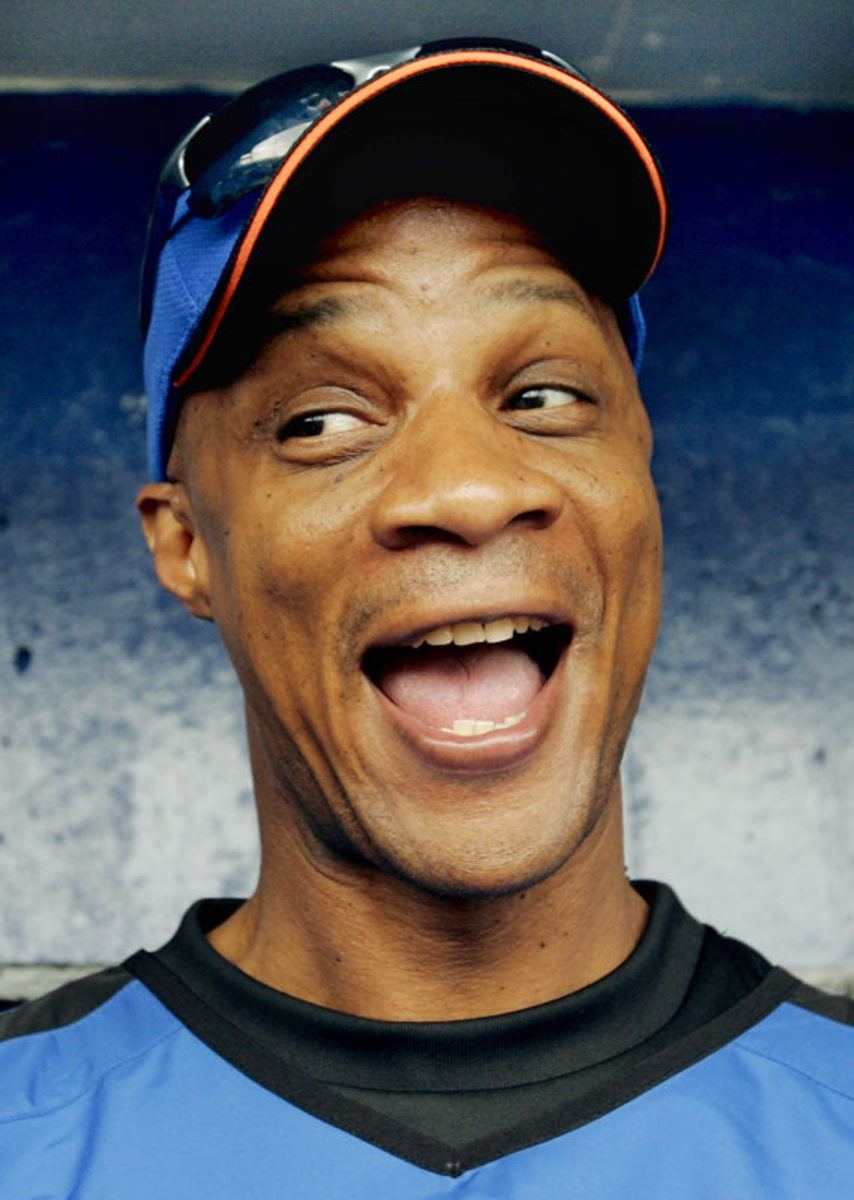

Paul Lo Duca

During Lo Duca's two seasons with the New York Mets, clouds gathered in a hurry over the married (to a Playboy model), four-time All-Star. Local tabloids were stuffed with tawdry tales of him playing slap and tickle on the side with a pair of 19-year olds, and that the Mets were concerned about his fondness for a wager. When the Mitchell Report came out in December 2007, there was the name Lo Duca on canceled checks to admitted steroid supplier Kirk Radomski.

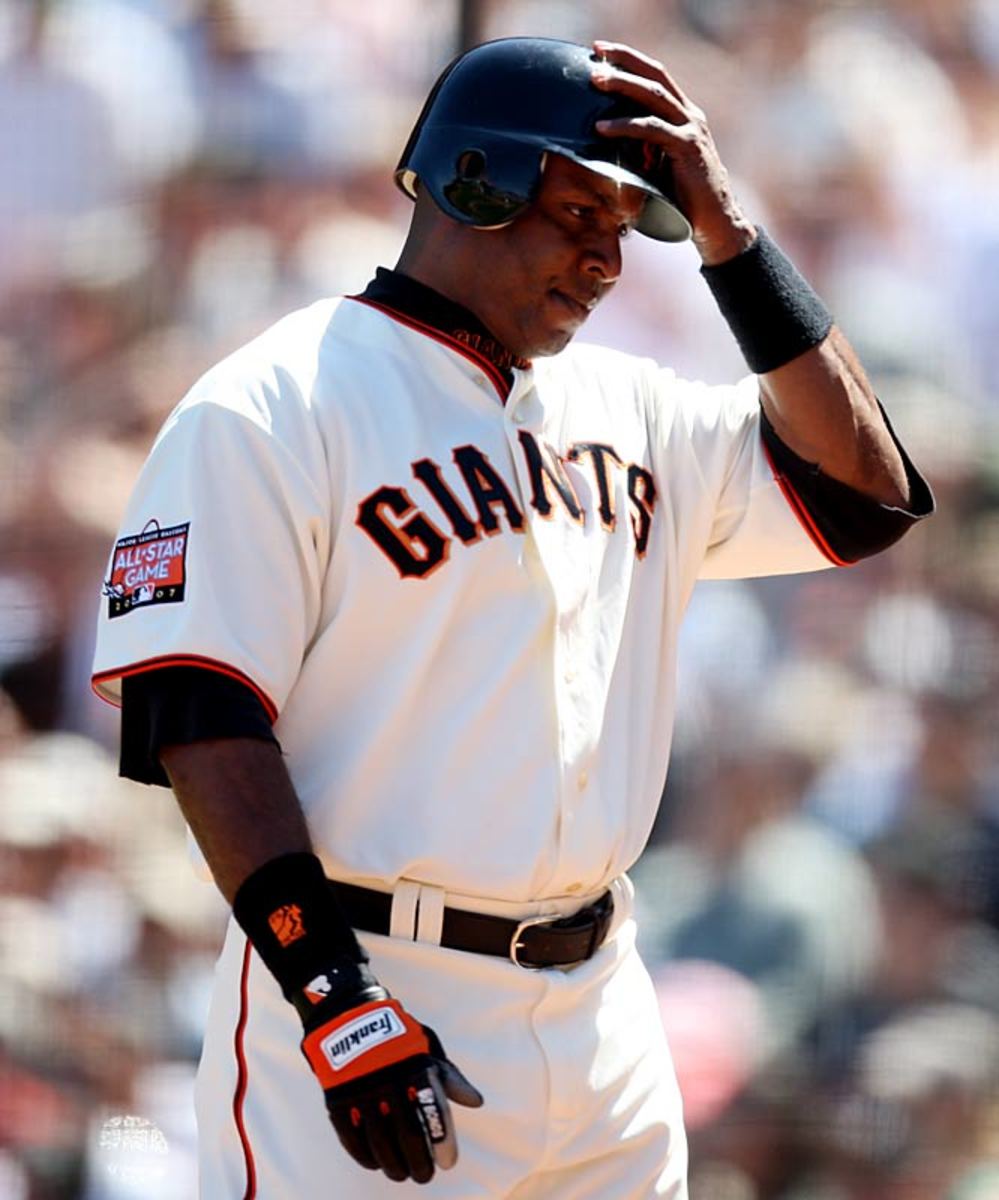

Barry Bonds

Baseball's all-time home run king is the puffy face of the steroid era even though he's maintained his innocence in the face of such evidence to the contrary that he's under indictment for perjury and obstruction of justice. Bonds took on extra mud in 2005 when Kimberly Bell began spilling that she'd been his longtime sugar on the side. There was also talk of the IRS looking into his failure to pony up on dough from memorabilia sales.

Ty Cobb

A member of the Hall of Fame's charter class of '36, the Georgia Peach was more the Georgia Lemon -- a mean-spirited, violent, racist misanthrope who attacked a groundskeeper and the man's wife in 1907, got suspended for going into the stands to stomp a fan in 1912, and was ultimately exonerated of fixing a game in 1919 though there was strong evidence of his guilt.

Darryl Strawberry

Heralded as a can't-miss superstar upon his 1983 arrival in the bigs, the prodigiously talented 6-foot-6 slugger's 17-season career with the Mets, Dodgers, Giants and Yankees was pockmarked by constant conflicts with teammates, drug suspensions, rehabs, arrests, jail time, a paternity suit and accusations of spousal abuse and tax evasion.

Jose Canseco

One of the A's famed Bash Brothers, Canseco became the oily whistle-blower of the steroid era with his book Juiced, in which he fingered Brother McGwire and Sammy Sosa, among others. He earned admiration for owning up to Congress in 2005, but his crusade against Alex Rodriguez now seems specious. Other testaments to character: a 2001 brawl at the Opium Garden nightclub in Miami that led to $240,000 in punitive damages and a two-year house arrest sentence, plus two divorces (price tag $7 million-$8 million) that have cost him his digs in California.

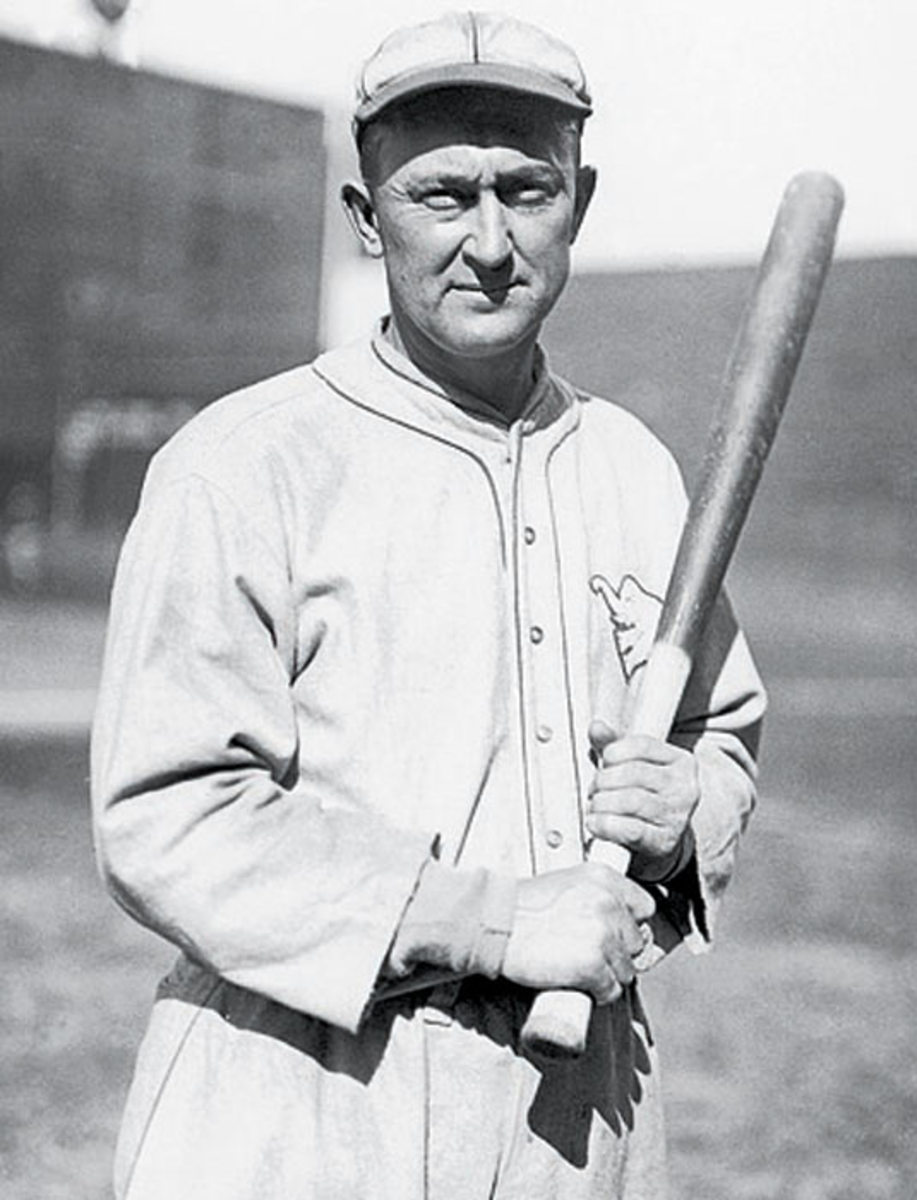

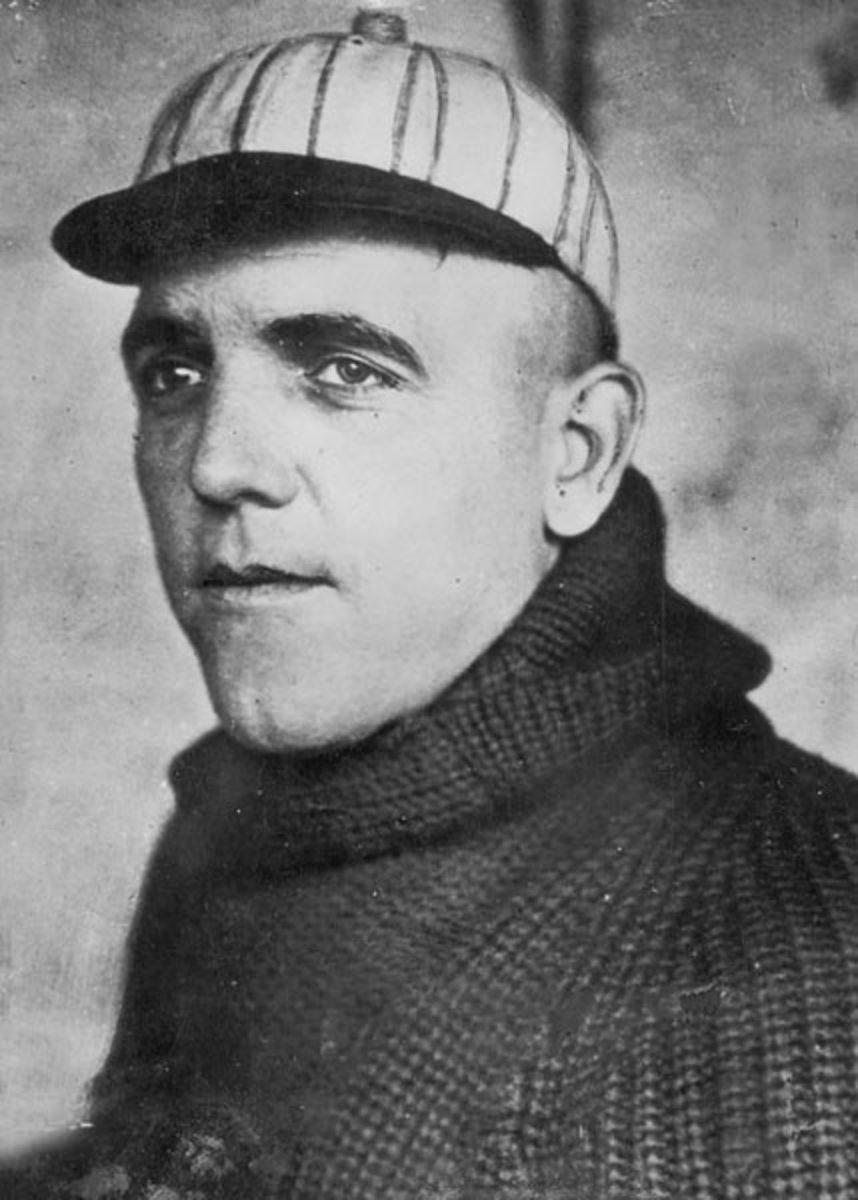

Eddie Cicotte

The veteran ace was 29-7 with a 1.82 ERA in 1919 before becoming one of eight key figures in the infamous Black Sox Scandal. Cicotte won 21 games the following season but admitted to a grand jury that he'd accepted $10,000 from gamblers to help fix the 1919 World Series in favor of Cincinnati. (He was 1-2 with a 2.91 ERA in 22 innings.) Cicotte and his conspirators were acquitted, then promptly banned from the game for life by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

Claude "Lefty" Williams

A 23-game winner on the Black Sox staff, Williams did his part in the fix by losing all three of his Series starts (a record that stood until 1981 when George Frazier of the Yankees tied it, presumably with honest intent), including getting knocked out of the box early in the final game. After winning 22 in 1920, Williams was given the bum's rush by Commissioner Landis.

Roger Clemens

The seven-time Cy Young Award-winner's cherished status as All-American icon and wholesome family man has taken a royal pounding ever since his former trainer Brian McNamee sang to Mitchell Report investigators that he'd injected Clemens with performance-enhancing drugs. After filing a defamation suit against McNamee, the Rocket was hit by claims that he'd dallied with dollies, including country singer Mindy McCready, who was only 15 when they met, and flew floozies on the team plane.

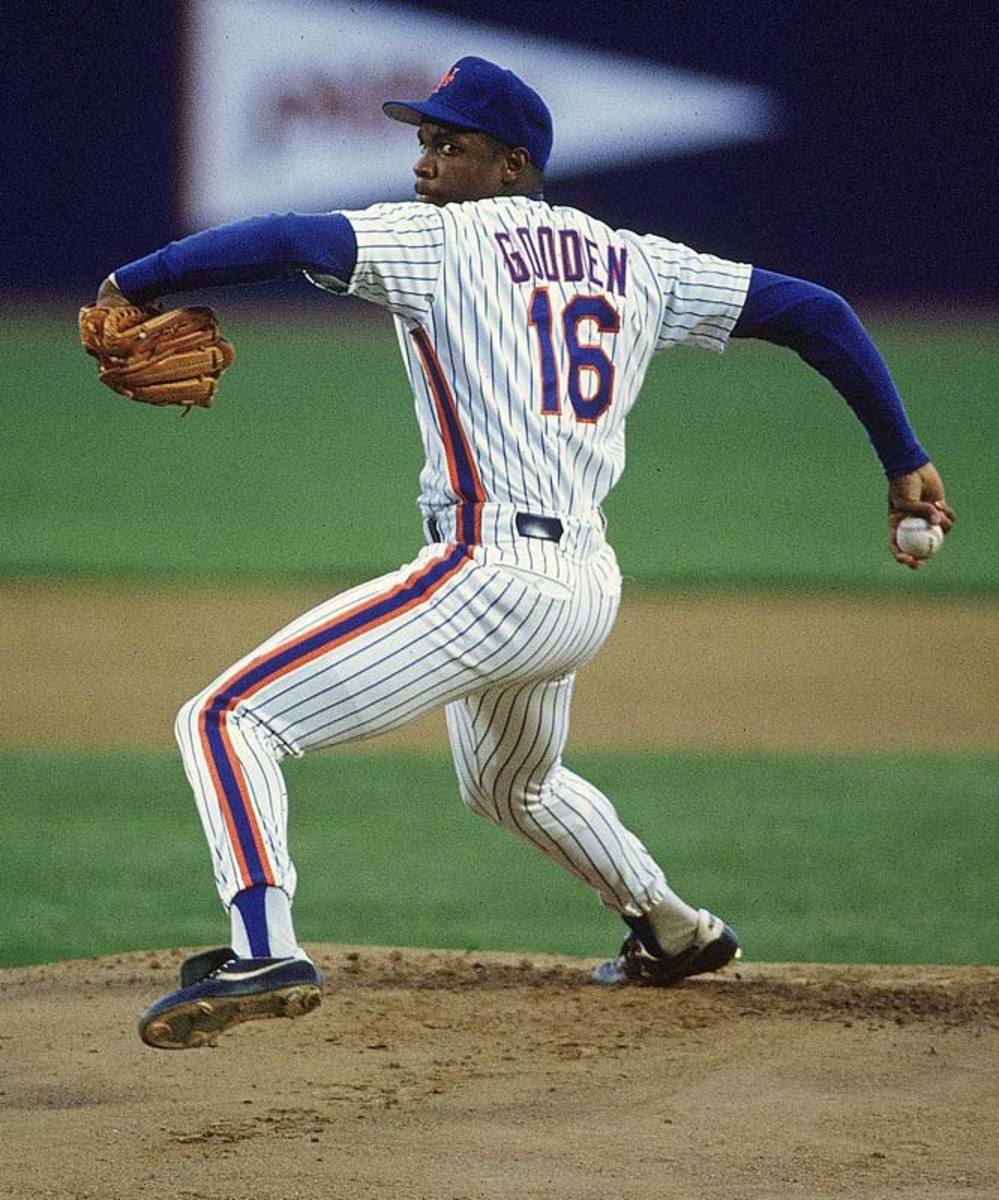

Dwight Gooden

The magic and promise of his 24-4, 1.53 ERA sophomore season in 1985 was steadily lost to drug and alcohol problems, which surfaced with a failed cocaine test in 1987. During his 16 seasons in the majors, and beyond, Dr. K logged a depressing ledger of suspensions, rehab stints, jail time and arrests for everything from fighting with cops to DUI to punching his girlfriend.

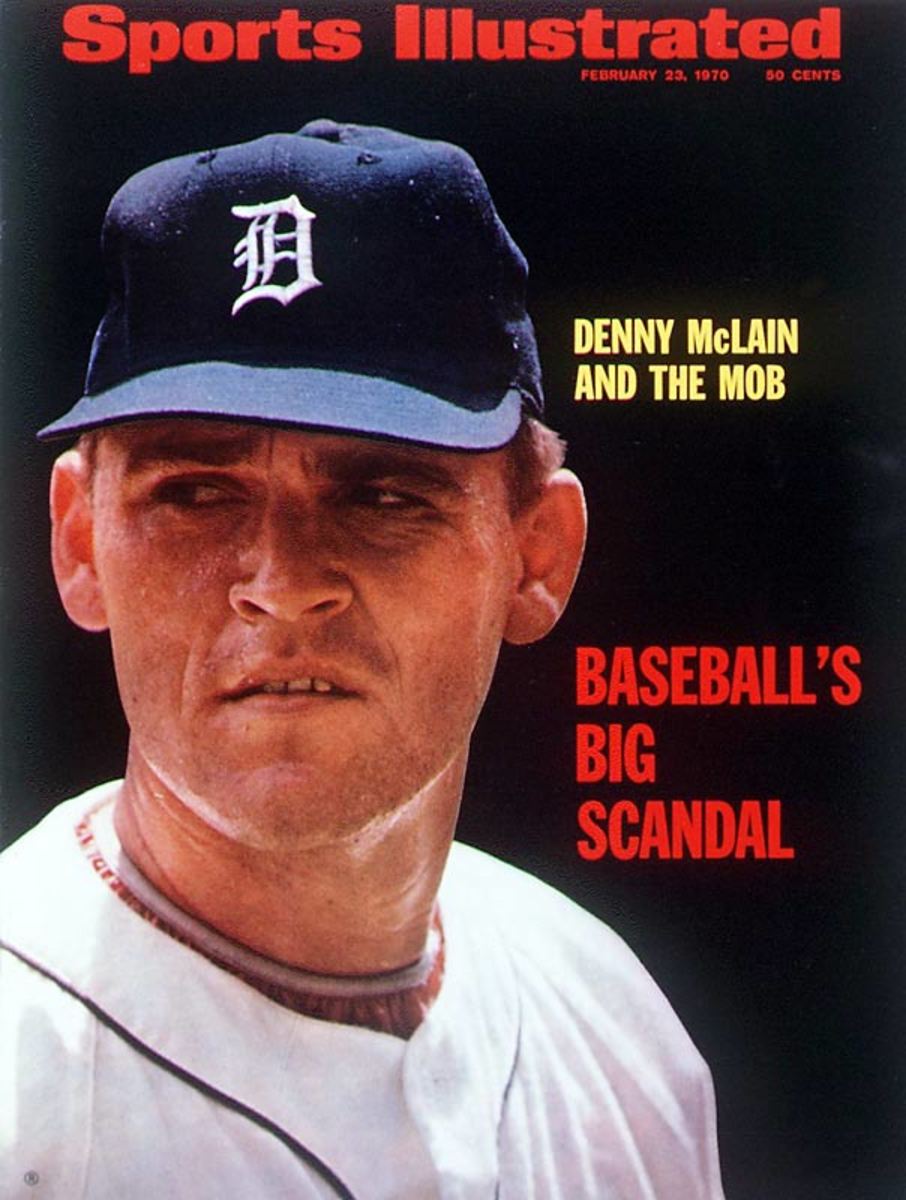

Denny McLain

A two-time Cy Young-winner, the last pitcher to win 30 games in a season (Detroit, 1968) was suspended three times in 1970 for consorting with reputed gamblers with mob ties, dumping water on sportswriters, and packing heat on a team flight. After injuries derailed his career, McLain got 23 years in prison for racketeering, extortion, conspiracy, and cocaine possession. His 1985 sentence was overturned two years later and he plea bargained his freedom, but.returned to the big house in 1996 for six years on an embezzlement rap.

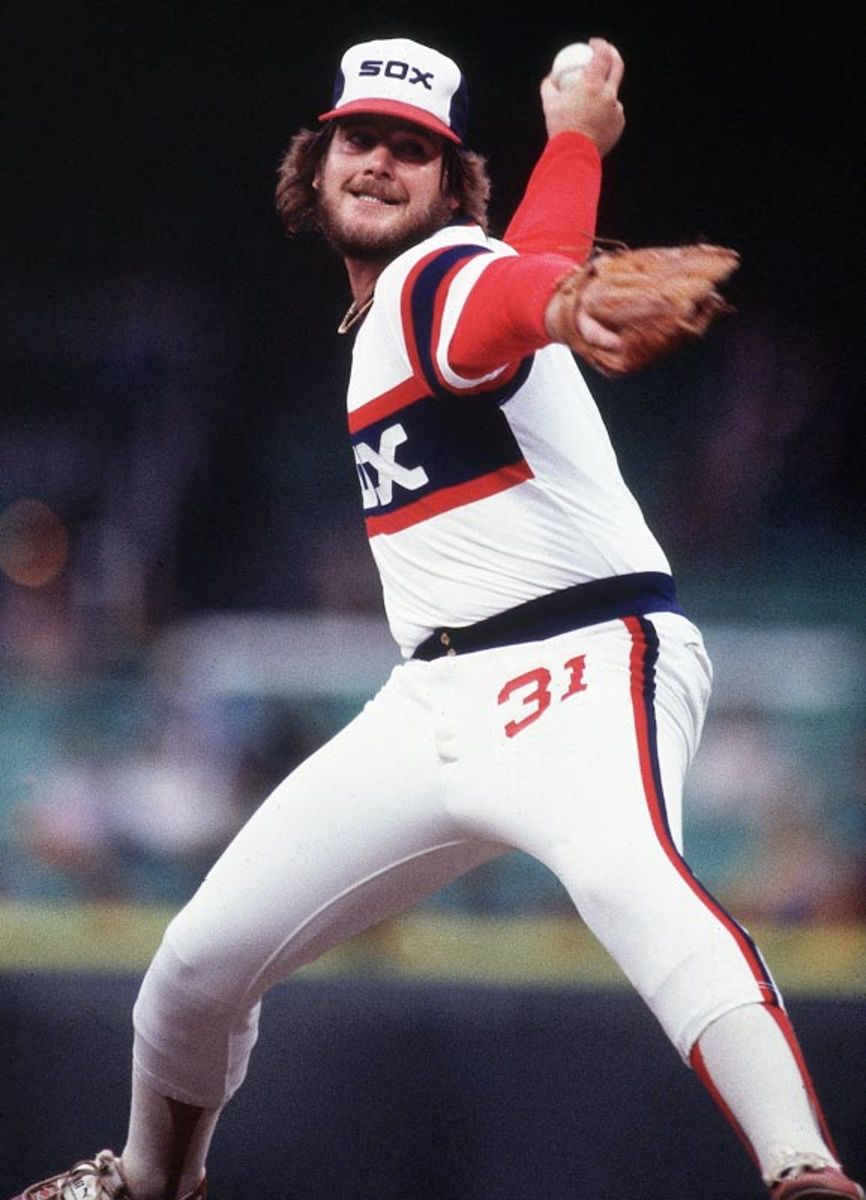

La Marr Hoyt

The 1983 Cy Young Award-winner with the White Sox was arrested twice in 1986 on drug possession charges and went into rehab. Not an auspicious start to a season in which he went 8-11 with a 5.15 ERA. Soon after, Hoyt was pinched again on the Mexican border and got 45 days in the jug. Commissioner Peter Ueberroth banned him for a year and that was it for a once-promising career.

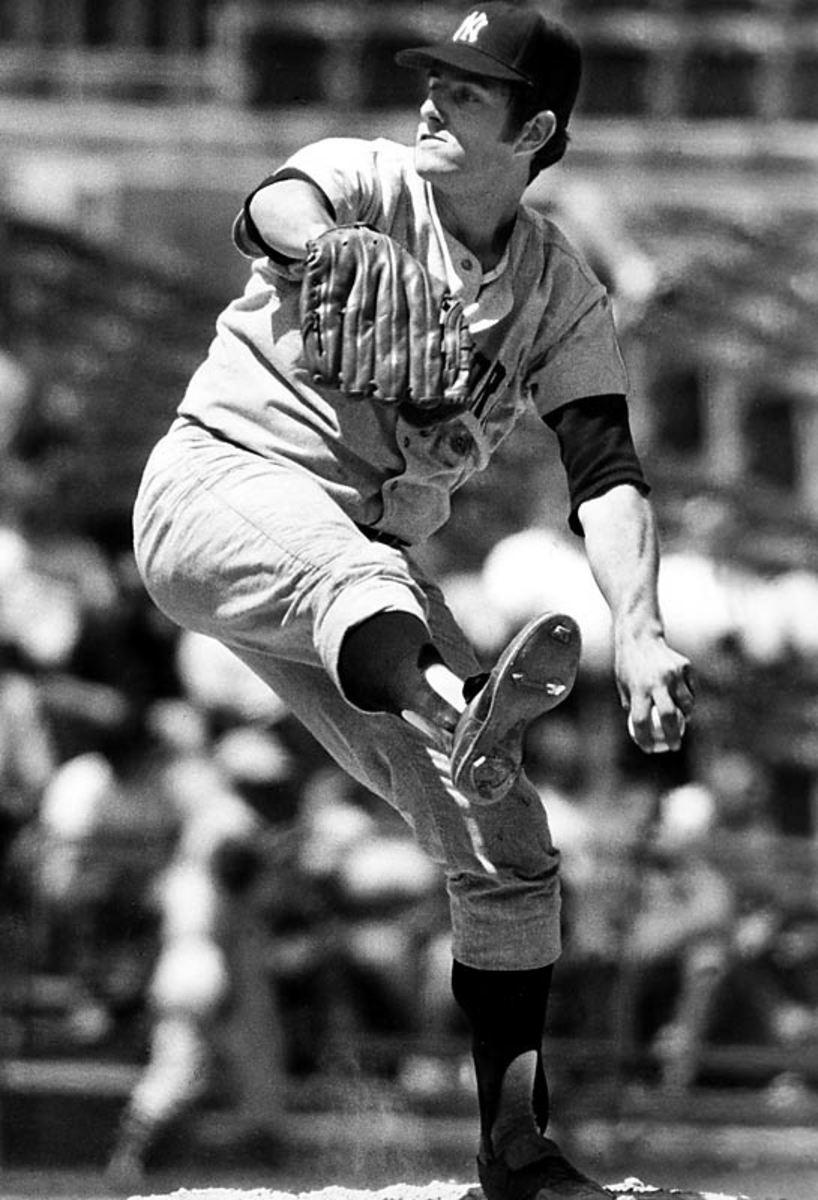

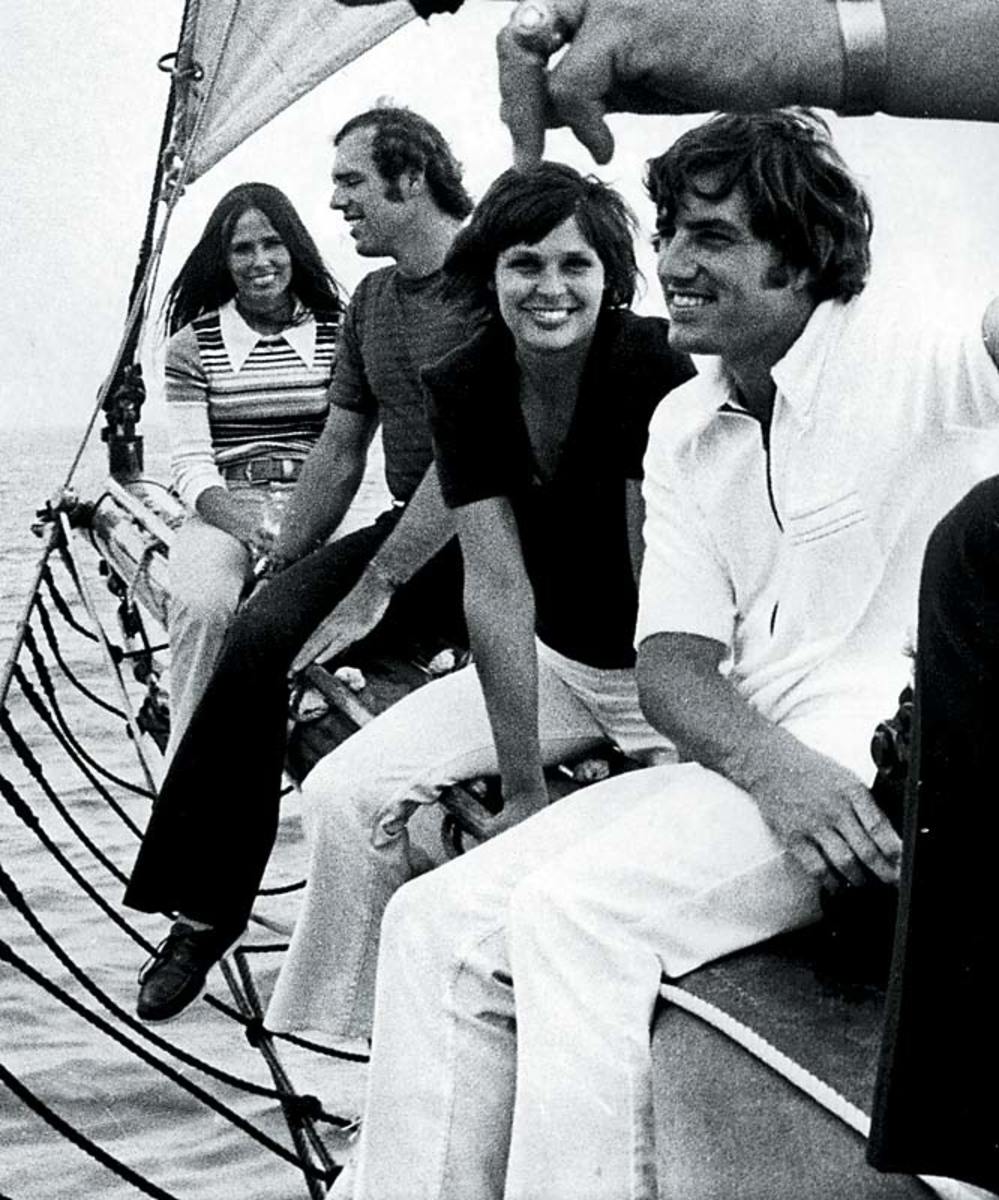

Fritz Peterson

In the pantheon of rogues, Peterson is a small potato, but stands as a central figure in one of baseball's most famous scandals. The ace southpaw of the Yankees will always be remembered not for his 20-win season in 1970, but that he made headlines at spring training in 1973 when he revealed he had swapped wives and lives (including houses and kids) with friend and teammate Mike Kekich. Peterson ended up marrying Sue Kekich and finding religion many years later.

Mike Kekich

Not noted for his moundsmanship, but Kekich (left) was the other half of the Yankees' notorious wife-swappers of 1973. When the Commissioner's office was flooded with indignant mail from an outraged public, the Yankees presented the southpaw with a one-way ticket to Cleveland. Peterson followed the following season, but Marilyn Peterson left Kekich. ''Neither Fritz Peterson nor I will ever make it into the Hall of Fame,'' he noted many years later.

Steve Howe

The 1980 NL Rookie of the Year fought a long, hard battle with cocaine that included seven suspensions, making him the poster child for drug abuse in pro sports. Given a sixth-chance in 1991 by George Steinbrenner, who later opened his arms and stadium to Dwight Gooden and Darryl Strawberry, Howe in 1992 became the second player ever to be banned for life due to substance abuse. He appealed the suspension and saved 15 games as the Yankees' closer in 1994.

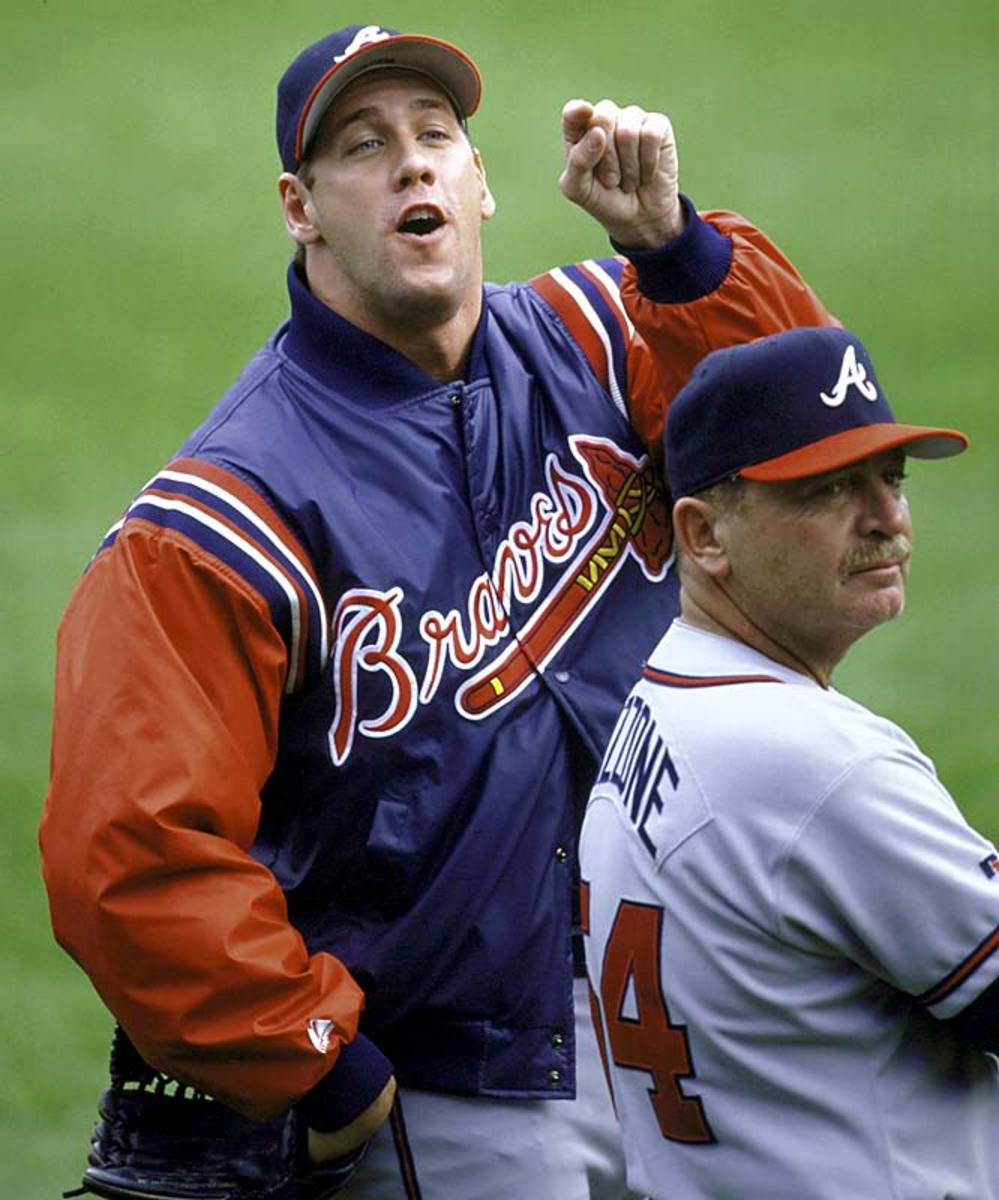

John Rocker

The outspoken lefty saved 38 games for the Atlanta Braves in 1999 and ignited a firestorm with his pie-hole by publicly denigrating New Yorkers, gays, Asian women and black teammate Randall Simon in an SI article. MLB-imposed sensitivity training didn't seem to have much effect -- he admittedly left after 15 minutes -- and his return to New York in 2000 required 700 police at Shea Stadium with security measures befitting a Bush visit to Osama's cave. By 2001 Rocker was on his way out of Atlanta and, ultimately, the majors.

Albert Belle

Surliness and swat went hand-in-fist with this moody slugger, who became notorious for hitting a fan with a thrown ball and spewing profanity at NBC's Hannah Storm during the 1995 World Series. The first player to belt 50 homers and 50 doubles in a season ('95) was also found to be a cheater. His corked bat was the object of a wacky case in 1994 when Indians teammate Jason Grimsley (a noted figure in the Mitchell Report) crawled through a ceiling to retrieve Belle's confiscated lumber from the locked umpire's room in Comiskey Park. In 2006 Belle was accused of stalking a woman in Arizona.

Mickey Mantle

The revered Yankee icon was portrayed as a hard-drinking carouser by teammate Jim Bouton in the 1970 book Ball Four, which created a mushroom cloud of controversy in baseball's presumably squeaky-clean domain. Mantle later admitted to distasteful personality flaws fueled by his voracious thirst for alcohol. Even after his 1995 death, his dark side has lived on, most recently in a salacious book.

Rafael Palmeiro

His adamant, finger-pointing insistence before a congressional hearing in 2005 that he had never used steroids proved disastrous five months later when he tested positive for stanozolol and was suspended. His claim of taking the drug unknowingly rang hollow and the brouhaha obscured the significance of his 3,000th career hit. The season proved to be his last.

Lenny Dykstra

The sparkplug center fielder of the 1986 World Series champion Mets was revealed in Jeff Pearlman's The Bad Guys Won as, well, a rowdy, reckless bad guy. As a Phillie in 1991, Dykstra was driving with a snootful of firewater when he wrapped his car around a tree, breaking his ribs, cheekbone and collarbone, and injuring teammate Darren Daulton. A 2004 lawsuit filed by a former business partner alleged that Dykstra bet on baseball and used steroids, an allegation also found in the Mitchell Report.

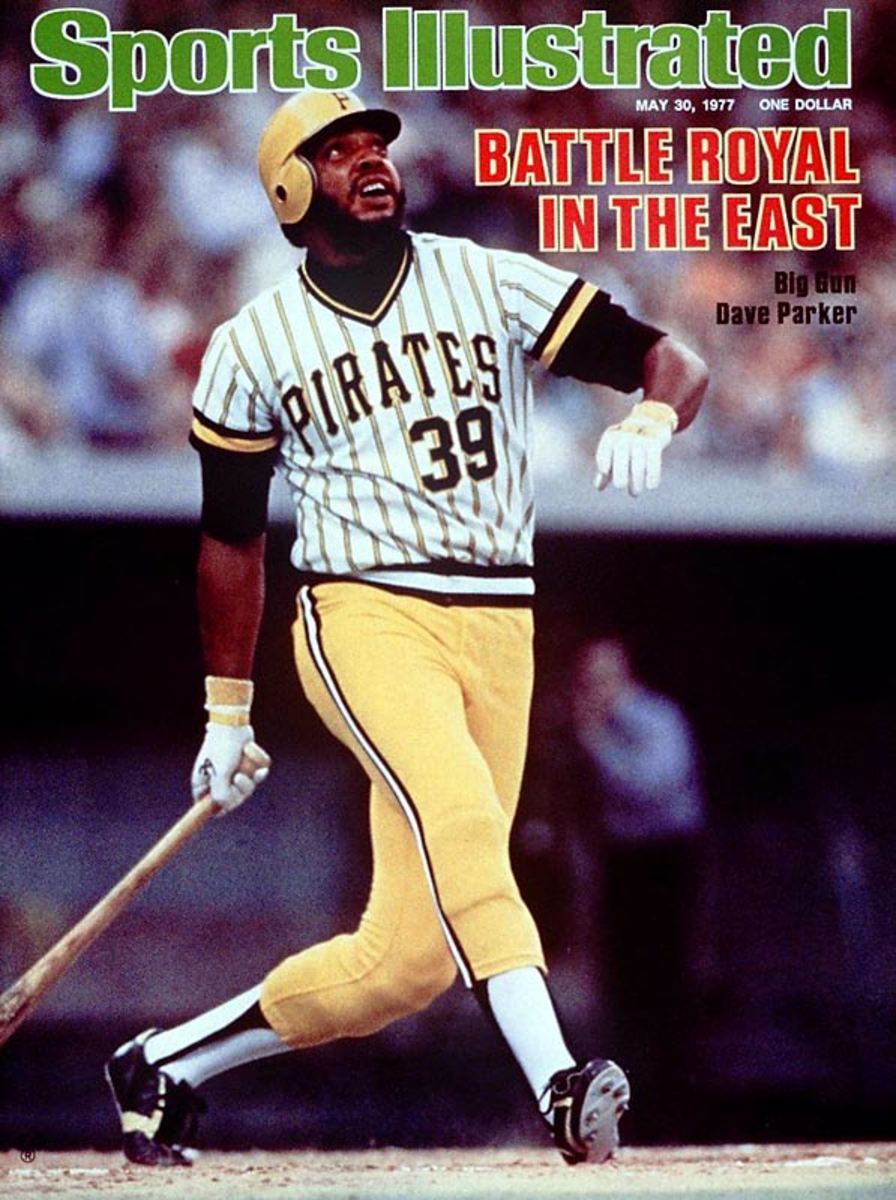

Dave Parker

The Cobra, a two-time batting champ and the 1976 NL MVP, was one of the biggest names in baseball's cocaine scandal of the 1980s. After testifying at the trial of one of suppliers, Parker was sued in Federal court by the Pirates, who were irked by the fact that they were on the hook for $5.3 million at a time when the slugger was proving that cocaine was not exactly a performance-enhancing drug. (His production had tailed off and he'd become bloated and prone to injury.)

Sammy Sosa

Mark McGwire's sunny foil from the Summer of '98 was slowly unmasked, first as a cheater when his bat broke during a 2003 game, revealing a cork center. Then came steroid allegations and an appearance before a congressional hearing in 2005 in which he suddenly lost the ability to understand English. Sosa sat out the 2006 season before attempting a comeback with the Texas Rangers, his physique noticeably smaller.

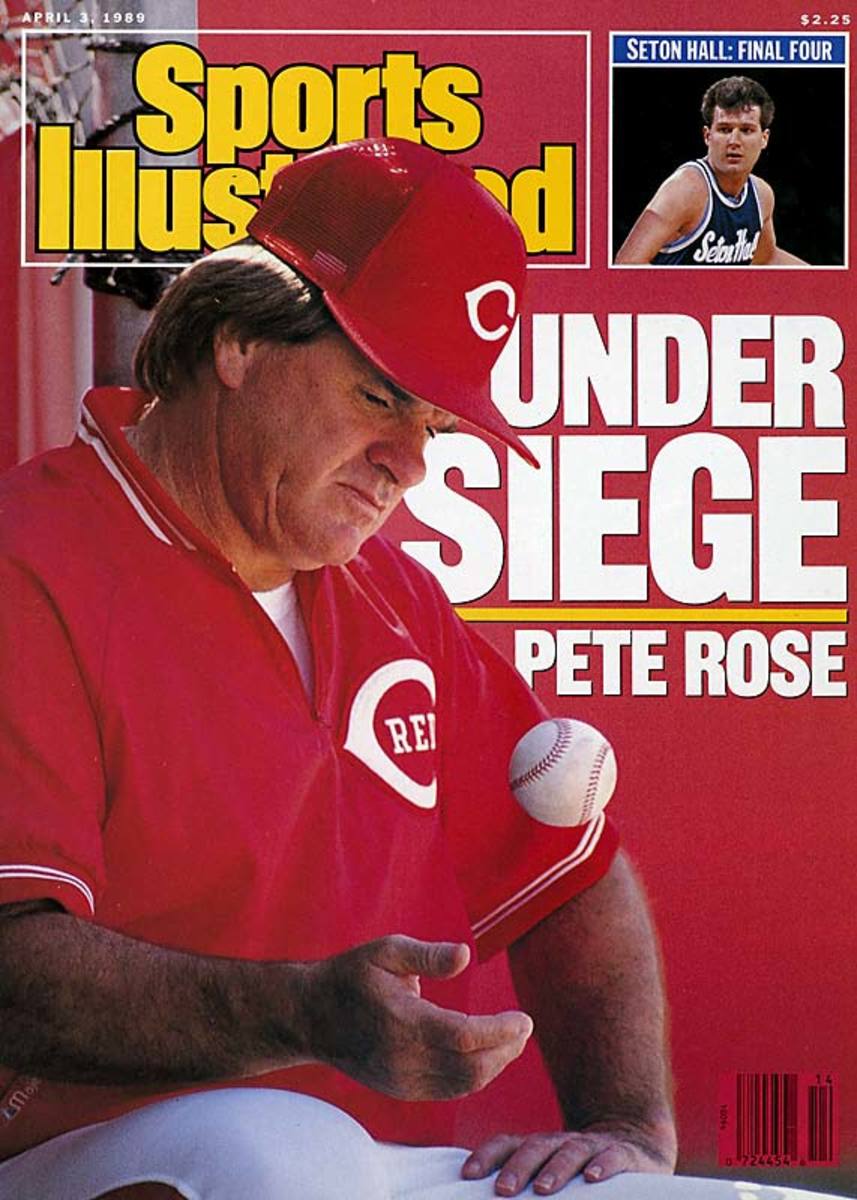

Pete Rose

Baseball's all-time hits leader was permanently banned in 1989 after an investigation revealed that he'd bet on baseball while managing the Cincinnati Reds. ''Despite what the commissioner said today, I didn't bet on baseball,'' Rose insisted, admitting that he only wagered on other sports. ''I made some mistakes and I'm being punished for mistakes.'' More mistakes and punishment followed, as Rose was jailed in 1990 for tax evasion. It wasn't until 2004 that he owned up to his baseball bets -- while peddling his book My Prison Without Bars.

Steve Phillips

Phillips built a formidable team that won the 2000 NL pennant but was hit by a former employee's sexual harassment suit that led to revelations of multiple affairs -- this at a time when the Mets were trying to fumigate an ugly image as a haven for miscreants, malcontents and lawbreakers. Phillips took a brief leave of absence in 1998 as local tabloids merrily dished the dirt, and settled the case out of court. He survived long enough to be fired in 2003 as the Mets floundered, and left baseball for a broadcasting career.

George Steinbrenner

He redeemed his image (no small feat), but the Boss in his blustery heyday was a perpetual scandal machine. He was suspended twice: for 15 months in 1974 for illegal campaign contributions to Richard Nixon, and for life (later reduced to two years) in 1990 after paying gambler Howie Spira to dig up unflattering stories about Yankees slugger Dave Winfield, with whom he had been feuding. Frequent fines for criticizing umpires and league officials also helped turn the staid Yankees into the Bronx Zoo.

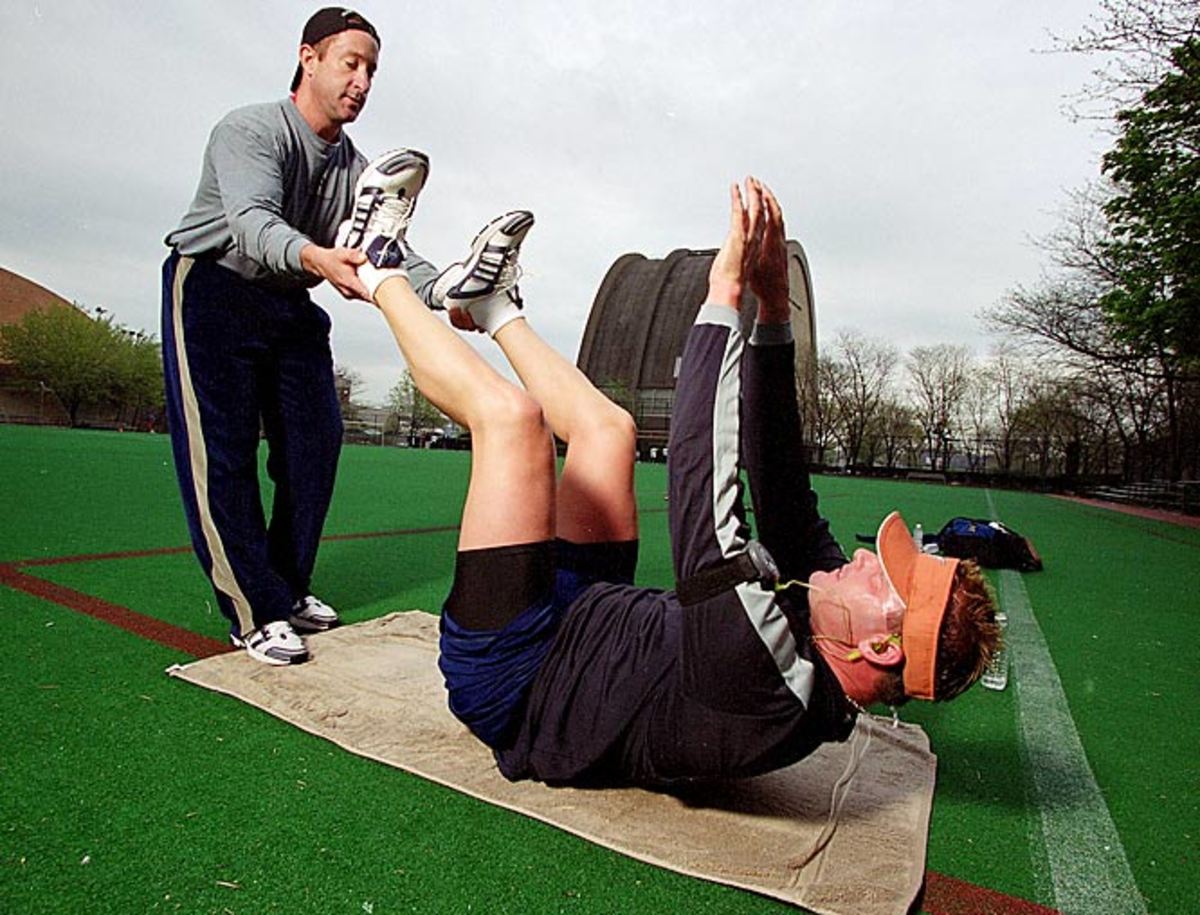

Brian McNamee

The central weasel in the Mitchell Report, McNamee worked as a fitness guru for the Yankees and Blue Jays, admittedly fixing up players with performance-enhancing substances.

Pirate Parrot

The bird became embroiled in baseball's cocaine scandal of 1985 when it was revealed before a grand jury in Pittsburgh that he'd introduced assorted members of the Pirates to a local drug peddler and had even distributed a little Peruvian coco powder himself. The Parrot avoided prosecution by cooperating with the FBI.