Examining the numbers behind the rise in no-hitters

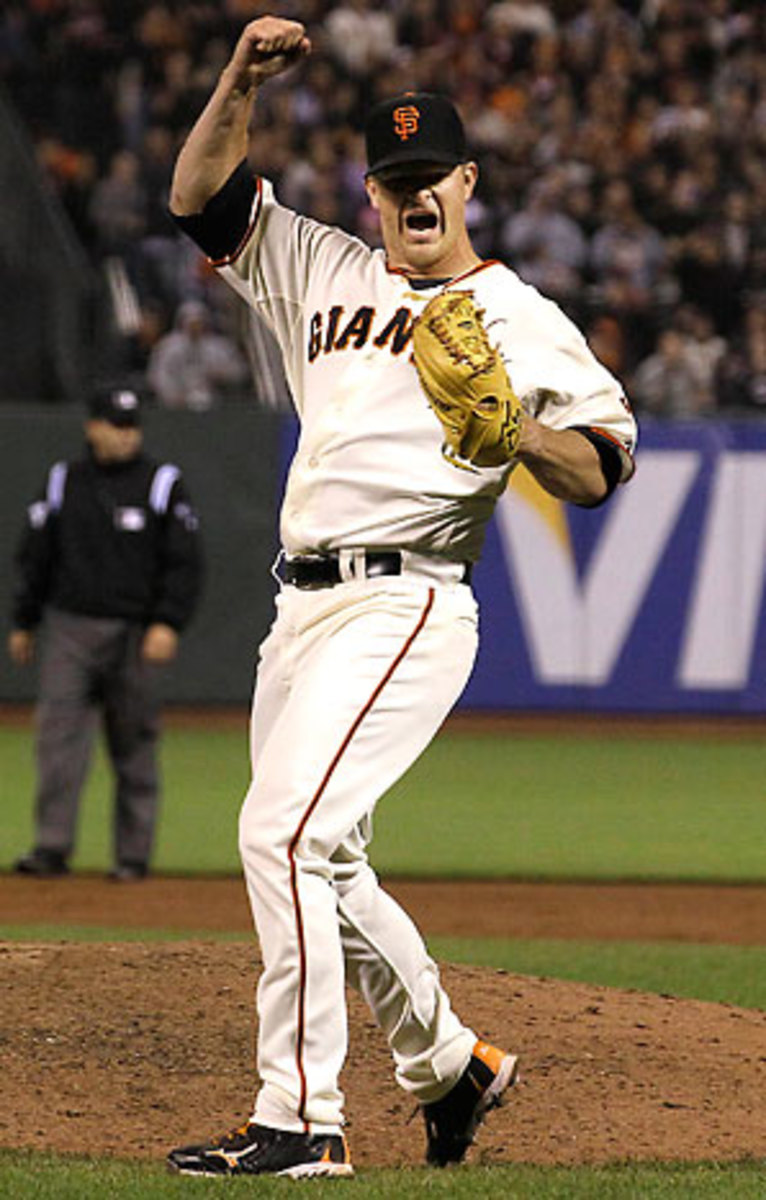

Perfect games haven't been as rare as they used to be but Matt Cain proved again they're still special. (AP)

No-hitters seem to be occurring as often as thunderstorms this spring. Matt Cain's perfect game was the second no-hitter in less than a week, following a six-pitcher combined effort by the Mariners on June 8, the third of the month going back to Johan Santana's gem on June 1 and the fifth of the season. No fewer than 14 no-hitters have been thrown since the beginning of the 2010 season, including Roy Halladay's Division Series effort, just the second in postseason history. To find a three-year stretch with more no-hitters, you'd have to go back to 1990-1992, when 15 were thrown -- seven in 1990 and 1991, plus one in 1992.

Those years with seven no-hitters are tied for the single-season major league record, a mark that suddenly appears in danger of falling; at the current rate, we'd finish the season with 13. Why are these jewels suddenly more commonplace? While luck and/or randomness has to be part of the explanation, the increased number is helped along by the collision of a few long-term trends, some of which are nestled inside of others.

1. More games. This one is almost too obvious, but with five rounds of expansion since 1960 (the first one spread over two years), and a lengthening of the schedule from 154 to 162 games, the major league slate contains nearly twice as many games as it once did. When the AL and NL each contained eight teams playing 154 games, from the dawn of the Modern Era in 1901 through 1960, a full season's schedule consisted of 1,232 games, or 2,464 opportunities for no-hitters. With 30 teams playing 162 games, a full slate is now 2,430 games, meaning 4,860 opportunities for no-hitters — a 97 percent increase over the pre-expansion era.

2. Lower batting averages. Fueled by expansion into better hitting environments such as Colorado and Arizona, steroids, and the changed composition of the baseball itself — a combination of factors I explored at length in Baseball Prospectus' Extra Innings: More Baseball Between the Numbers — the game experienced its most sustained swell of offense since the 1930s from 1993-2009. Scoring levels were at or above 4.59 runs per team per game in every season, and home run rates were above 1.0 per game. Since 2010, scoring is down slightly, though this year's 4.30 runs per game is actually 0.02 above last year's mark, which was the lowest since 1992 (4.12). Meanwhile, this year's 0.99 home runs per game is slightly higher than last year's 0.94, which was the lowest since 1993 (0.89).

While power levels are still higher than they were in the pre-1993 era, the major league batting average is lower than it's been in four decades, after going as high as .271 in 1999, and reaching .270 three times from 1994-2000. This year, batters are hitting .253, the lowest mark since 1972, when it was .244. That, of course, was the year before the designated hitter was introduced in the American League, an innovation — or abomination, depending upon where you sit — designed to inject more offense into the game. From 1988-1992, the stretch just preceeding the aforementioned offensive boom, the major league batting average ranged between .254 and .258. That's quite comparable to the last three seasons, when it's fallen from .257 to .255 to .253.

3. Higher strikeout rates. This year, pitchers are striking out batters at a rate of 7.50 per nine innings. That's far and away a record, beating the 7.13 mark reached in each of the past two seasons. Strikeouts have been increasing steadily since 1981, when they were at 4.75 per nine innings; they haven't fallen below 5.00 per nine since then, haven't dipped below 6.00 since 1994 and have stayed above 6.40 in every year since 1996 save for 2005, when they slipped to 6.38 in 2005. Strikeout rates increased in every single year since then.

The increased strikeout rates themselves represent a combination of factors. For ages, strikeouts carried a stigma for hitters — the scarlet letter K, so to speak. But as statheads have pointed out for the past few decades, a strikeout is just another out. Swinging and missing or taking a hittable pitch may not look pretty, but it won't produce a rally-killing double play. Strikeouts actually have a positive correlation with slugging percentage, isolated power (slugging percentage minus batting average), and walk rates, all factors that increase scoring.

As more people inside and outside the game have realized this, the stigma has lessened considerably. Consider that Bobby Bonds' single-season record of 189 strikeouts, set in 1970, stood until 2004, when it was broken by Adam Dunn; so great was the stigma that players such as Rob Deer and Jose Hernandez were benched during the season's final weeks to avoid the shame of breaking the record. Since Dunn whiffed 195 times in 2004, the record has been broken three times, first by Ryan Howard and then by Mark Reynolds twice, with a high of 223 in 2009. Bonds' mark now ranks 12th on the single-season list.

4. Better defense. While higher strikeout rates mean fewer balls in play, teams have recently been squelching slightly more balls that are put in play and it's that combination that is responsible for lower batting averages. This year, the majors' defensive efficiency rate, which measures how often teams convert batted balls into outs, is at .709. That mark isn't particularly special in and of itself; it was .709 last year, and ranged between .707 and .709 four times since 2003, when it was at .711. That was the highest mark since 1992, but in the 1970s and 1980s, it often exceeded .720, and went as high as .736 back in 1968, the year of the pitcher. When you combine the recent localized high with the increased number of strikeout rates, hits are suddenly more scarce.

As to why teams are more successful at converting batted balls into outs, one reason may be because of better positioning of fielders, itself a product of teams putting an avalanche of data to use. Several companies track the location of each batted ball, providing that data to teams at a price in ways that can be sliced and diced with increasing sophistication. For example, Baseball Info Solutions, which is one of those companies, can tell you that Howard pulls 89 percent of his groundballs and short liners to the right of second base. As information like that has been disseminated to teams, BIS has begun tracking infield shifts, such as the ones that pull hitters like Howard, Dunn, Mark Teixeira and Carlos Pena regularly face, where the shortstop moves to the right of second base. The trend is catching on. According to BIS, in 2010 and 2011, teams shifted around 1,900 times, but as of mid-May, they were on pace for twice that number. Research isn't entirely conclusive that the shift is effective, but the team that has used it more often than any other, the Rays, led the majors with a .724 defensive efficiency last year, 30 points higher than the major league average and 19 points higher than any other team.

Put those factors together and you've got an increased chance of a no-hitter on any given night, one that might be aided by a psychological aspect: if a pitcher carries a no-hitter into the later innings, his fielders are more likely to be on their toes, and willing to lay out for a spectacular and risky play such as the one that the Mets' Mike Baxter made in Santana's no-hitter. Baxter crashed into the left field wall, injuring his shoulder while robbing Yadier Molina of a hit in the seventh inning; he was forced not only from the game but to the disabled list. In the seventh inning of Cain's perfecto, Gregor Blanco skidded on the warning track to make a diving catch that prevented Jordan Schafer from getting a hit; fortunately, he was able to walk away unharmed. The scores in both of those games were lopsided by the time those balls were hit — 5-0 for the Mets and 10-0 for the Giants — and it's likely that neither player would have risked injury had a no-hitter not been on the line.