JAWS and the 2013 Hall of Fame ballot: Edgar Martinez

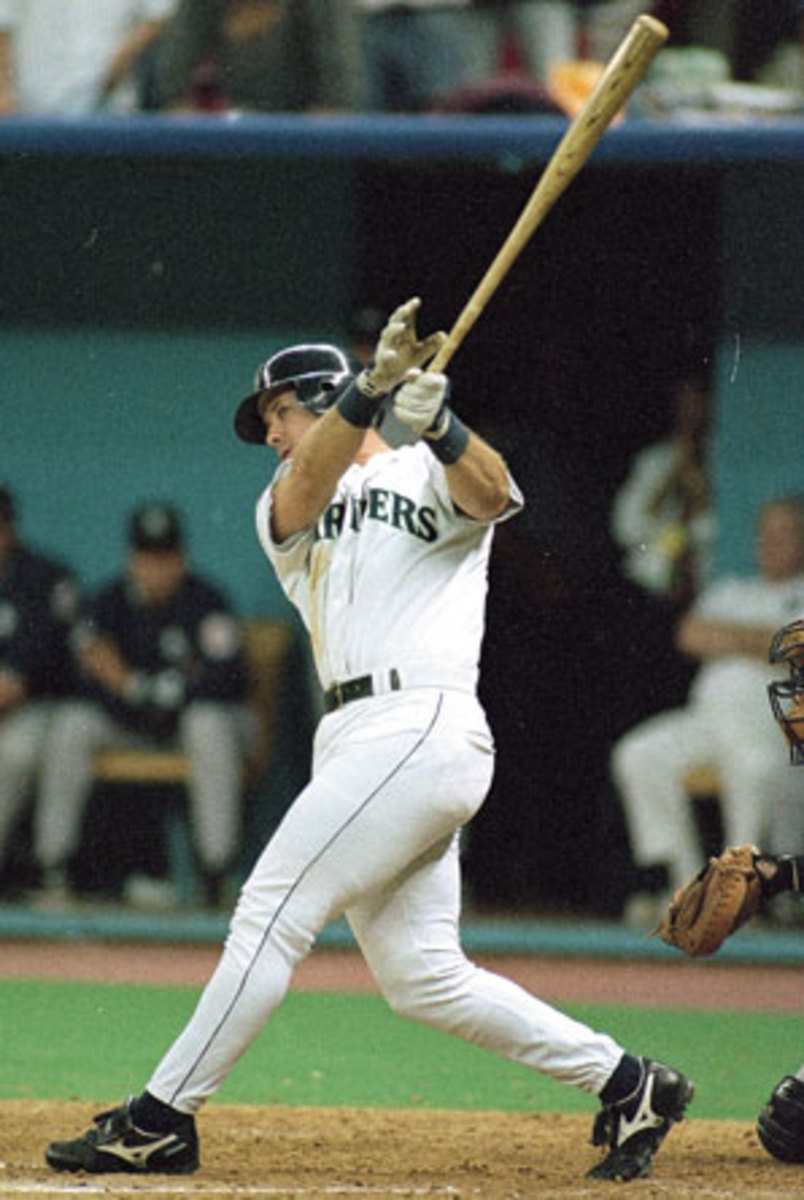

Edgar Martinez's series-winning double in the 1995 ALDS was arguably the biggest hit of his career. (V.J. Lovero/SI)

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2013 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here.

The 2013 season will mark the 40th anniversary of the designated hitter's introduction into Major League Baseball, a rule change that continues to rankle purists who apparently would rather watch pitchers risk injury as they flail away with ineptitude (though that's a story for another day…). In that time, only one player who has spent the plurality — not the majority — of his time at the position has been elected to the Hall of Fame: Paul Molitor, who spent 1,171 of his 2,683 career games riding the pine between plate appearances.

When I reviewed Molitor's Hall of Fame case in 2004 — in what was actually my Baseball Prospectus debut, at a point when my system wasn't even called JAWS — I considered Molitor as a third baseman, because he had spent 788 games there, and the majority of his games playing somewhere in the infield. He had generated real defensive value (26 Fielding Runs Above Average according to the measure of the time) that strengthened a case that was virtually automatic by dint of his membership in the 3,000 hit club.

I have maintained that precedent in examining other candidates who spent good chunks of their careers at DH, mainly outfielders (Harold Baines, Jose Canseco, Chili Davis) with no real shot at gaining entry to Cooperstown, in part because JAWS enables easy comparisons with Hall of Famers not only at a given position but with the at-large field of enshrined hitters. I stick to that precedent in examining the case of Edgar Martinez, who ranks fourth on the all-time list for games by a DH at 1,403, but who also played 564 games at third base and another 28 at first base. I've compared Martinez to Hall third basemen, Hall corner infielders and Hall hitters in general, mainly because when properly used, JAWS is a tool used to build an argument, not a simple yes/no question.

No matter his position, Martinez could flat-out rake. A high-average, high-OBP hitting machine with plenty of power, he played a key role in putting the Seattle Mariners on the map as an AL West powerhouse, and emerged as a folk hero to a fan base that watched Ken Griffey Jr., Randy Johnson and Alex Rodriguez lead the franchise's charge to relevancy, only to force their ways out of town over contract issues. Today is Martinez's turn at bat.

Player | Career | Peak | JAWS | G | H | HR | SB | AVG | OBP | SLG | TAv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Edgar Martinez | 64.4 | 41.8 | 53.1 | 2055 | 2247 | 309 | 49 | .312 | .418 | .515 | .321 |

Avg HOF 3B | 64.9 | 41.8 | 53.4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Avg CI (1B+3B) | 63.1 | 41.2 | 52.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Avg HOF Hitter | 64.7 | 41.3 | 53.0 |

Though he was born in New York City, Martinez was raised in Puerto Rico, moving there as a young child after his parents' divorce. He played ball at the island's American College, and was signed by the Mariners as a non-drafted free agent in 1982 (not until 1990 did Major League Baseball make Puerto Rico subject to the amateur draft, a move that hasn't worked out for the island's best interests, baseball-wise). Just shy of 20 when he signed — old for a prospect — he didn't break out until his age-24 season in 1987, when he was in Triple-A. He received cups of coffee from the Mariners in 1987 and 1988, and struggled so mightily in 1989 (.240/.314/.304 in 196 PA) after opening the season as the team's third baseman that he was briefly sent back down. It wasn't until 1990, his age-27 season, that he stuck in the majors, but he put up strong numbers (.302/.397/.433, 5.3 WAR, +13 defense according to Total Zone) that season, and a year later helped the Mariners crack .500 for the first time since their 1977 inception.

In 1992, Martinez won his first AL batting title, hitting .343/.404/.544 with a league-leading 46 doubles; his 6.3 WAR tied with 2013 ballot-mate Kenny Lofton for fourth, behind only Roberto Alomar, Frank Thomas and Kirby Puckett. Alas, Martinez was limited to just 131 games combined the next two seasons due to hamstring and wrist injuries as well as the players' strike. The latter season led Seattle to relieve him of his defensive responsibilities; he was actually seven runs above average at the hot corner according to Total Zone, but his bat was far more important than his glove. It's fair to say the decision paid off.

In 1995, Martinez set a career-high with 6.7 WAR, hitting .356/.479/.628, leading the league in batting average, on-base percentage, True Average (.359) and doubles (52), and helping the Mariners to their first playoff berth in franchise history. No hit of his was bigger than The Double off the Yankees' Jack McDowell in the 11th inning of the decisive Game 5 of the Division Series, bringing home the tying and winning runs. The euphoria of that moment helped generate the groundswell of support that secured the Mariners a new taxpayer-funded stadium within a week of the series ending. Martinez was a one-man wrecking crew in that ALDS, batting .571/.667/1.000 with four-three hit efforts, reaching base safely 18 times in five games. He's still the co-holder of the record for most hits in a Division Series, with 12, and his 21 total bases rank fifth. Meanwhile, the Double is on the short list of hits that have taken on a life of their own.

The 1995 season began a seven-year stretch in which Martinez hit a combined .329/.446/.574 while averaging 42 doubles, 28 homers, 107 walks and 5.5 WAR per year (38.6 total). Defensive value is built into WAR, but even with negative value in that area (he played 33 games at third and first in that span), he tied with Mike Piazza as the majors' sixth-most valuable position player during over those years behind Barry Bonds (55.3), Alex Rodriguez (45.2), Jeff Bagwell (43.5), Ken Griffey Jr. (39.4) and Sammy Sosa (39.0). The Griffey comparison is particularly startling; the centerfielder on those Mariners teams won an MVP award and four Gold Gloves in that same span, and led the AL in homers for three years in a row (twice with 56) — and he was just a fraction of a win more valuable than Martinez during that period.

The Mariners reached the playoffs three more times in that 1995-2001 period, including their record-tying 116-win 2001 campaign after Johnson, Griffey and Rodriguez had all departed. Martinez was hardly a window dresser for that team, hitting .306/.423/.543 with 40 doubles, 23 homers, a .337 True Average (second in the league) and 4.5 WAR. He played three more seasons, hitting well for two of them, before retiring.

Martinez isn't the first Hall of Fame candidate to benefit from spending his twilight years as a designated hitter; Molitor reached Cooperstown largely because of what he did there. Nonetheless, Martinez's case is an interesting test for the voters. He played so few games in the field not only because he established himself at a relatively advanced age but because the risk/reward payoff wasn't merited once he emerged as an elite hitter, though it's likely the Mariners could have stuck him at first base — a much easier position than third, requiring less mobility — had they desired.

It's also worth considering that Martinez played in an era of increased specialization, particularly with regards to bullpen roles. Teams concerned with the limitations of a pitcher's stamina, health and/or repertoire often convert starters to relievers, who rarely produce enough value within their smaller roles to merit consideration for the Hall. Mariano Rivera is the best example; it's quite possible he'd have never approached a Hall of Fame level had he remained a starter. Martinez was the Mariano Rivera of DHs, so good within his limited role that he produced enough value to transcend it.

(Oh, and by the way, he owned Rivera: .579/.652/1.053 in 23 PA. Small sample size, but wow.)

Martinez falls a few runs short of the Hall of Fame standards at third base, behind on career but dead even on peak. He's slightly above the standards when compared to corner infielders, and a whisker above when compared to all hitters; such small differences to the right of the decimal either above or below are subject to the tiniest adjustment in WAR. While he's borderline on JAWS, the weight of the non-JAWS factors — the late start to his major league career, the black and gray ink (two batting titles and a second place, three OBP titles and three second places, two True Average leads and seven top five finishes), seven All-Star appearances, his all-time rankings in OBP (15th among hitters with 7,000 PA) and True Average (31st), the impact of the 1995 postseason upon Seattle baseball history — augment his case enough to push him over the line.

Voters have been slow to come around to that conclusion, though Martinez does have a substantial bloc of support. Three years into his eligibility, his highest share of the vote has been 36.5 percent, just under half of what he needs. That's not a lost-cause level in terms of modern voting history; Bruce Sutter (29.1 percent), Duke Snider (21.2 percent), Bert Blyleven (17.4 percent), Bob Lemon (16.6 percent) and Luis Aparicio (12 percent) all eventually were elected by the BBWAA after polling even lower in their third years, and Jim Rice was at 37.6 percent. Ten other players polled lower at that point but were elected via the various Veterans Committees.