JAWS and the 2013 Hall of Fame ballot: Mike Piazza

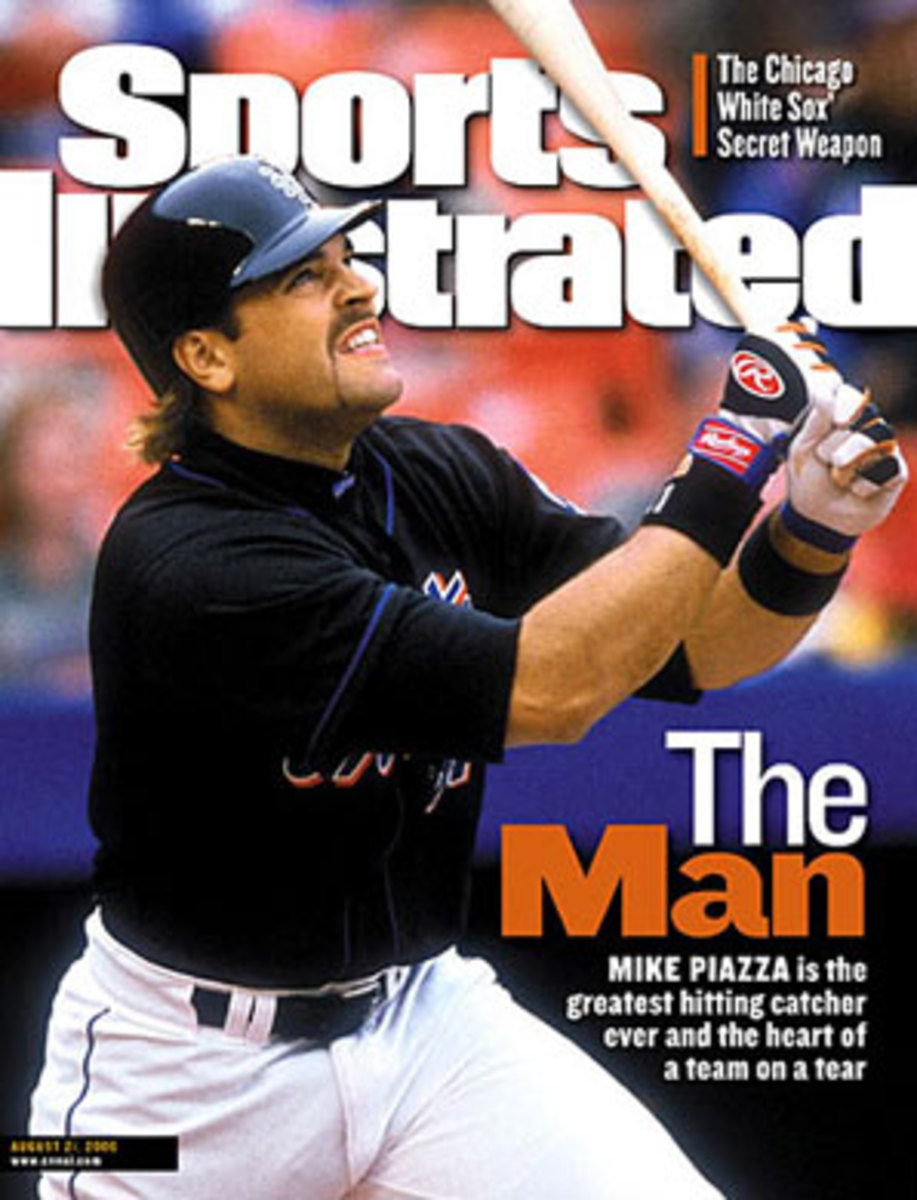

At his peak, Mike Piazza was already thought of as a legend. (John Iacono/SI)

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2013 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here.

By definition, it's not often that a player who was the very best at something comes up for election to the Hall of Fame. Stepping aside from the various controversies, this year's BBWAA ballot offers the all-time home run leader in Barry Bonds, and a pitcher with a strong claim as the best since World War II in Roger Clemens. Somewhat overlooked is the presence of Mike Piazza, who not only ranks among the best hitters of the era, but can lay claim to the title of the best-hitting catcher of all-time. Had he not spent the entirety of his 16-season career in pitcher-friendly ballparks or lost 10-20 games a year due to the demands of his position, he might have put up numbers that were even more staggering.

Though he was no Bonds or Clemens, Piazza was a controversial character during his 16-year career. He was run out of town by the Dodgers amid a high-profile contract dispute, his defensive skills were often questioned, he was a target in beanball wars and rumors about his lifestyle and links to performance-enhancing drugs made for tabloid fodder. Some of that is germane to his case for Cooperstown, much of it is not.

Player | Career | Peak | JAWS | G | H | HR | SB | BA | OBP | SLG | TAv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mike Piazza | 56.1 | 40.7 | 48.4 | 1912 | 2127 | 427 | 17 | .308 | .377 | .545 | .313 |

Avg HOF C | 49.3 | 32 | 40.7 |

Piazza was born in Norristown, Pennsylvania, the son of a high school dropout turned used car magnate named Vince Piazza, who as it so happened was a childhood friend of longtime Dodger manager Tommy Lasorda. In fact, Lasorda was the godfather of one of Vince's sons, his namesake Tommy Piazza, and he would let Tommy's older brother Mike serve as the Dodgers' bat boy when they came to play the Phillies. Years later, when Mike was playing first base for Miami-Dade Community College, his father asked Lasorda for the Dodgers to draft his son. Lasorda spoke to scouting director Ben Wade, who agreed only after being told that Piazza was willing to learn to catch. He was selected in the 62nd round of the 1988 draft with the 1,390th pick; only six other teams were still drafting at that late point.

Piazza signed for a $15,000 bonus and struggled to learn his new position. "I was running back to the screen like a Labrador three times a game," he later recounted of his time in the Florida State League during his second season. He even went to the Dodgers' baseball academy in the Dominican Republic for extra instruction, something virtually unheard-of for non-Latino players. For all of his troubles picking up the position, Piazza showed he could hit, and he rose through the team's farm system, debuting in the majors on Sept. 1, 1992, and cracking Baseball America's Top 100 Prospects list at number 38 the following spring.

The Dodgers had let 33-year-old Mike Scioscia depart as a free agent that winter, and gave Piazza the nod as their starting catcher on Opening Day of the 1993 season. He was an instant success, hitting .318/.370/.561 with 35 homers, impressive numbers given that Dodger Stadium still rated among the league's top pitchers' parks. Piazza's 6.8 Wins Above Replacement ranked second in the league behind Barry Bonds (9.7), while his slugging percentage ranked fourth and his batting average seventh. He was unanimously voted NL Rookie of the Year, the second of five consecutive Dodgers to win the award (Eric Karros won in 1992, while Raul Mondesi, Hideo Nomo and Todd Hollandsworth followed Piazza). The Dodgers went just 81-81 that year, a vast improvement on their 63-99 season in '92; Piazza's two homers on the final day helped beat the 103-win Giants, leaving them a win short of the Braves in the NL West. Lasorda savored the victory, to say the least.

Piazza proved that his rookie season was no fluke by putting up similar or even better numbers over the next few years. He hit .346/.400/.606 with 32 homers in the strike-shortened 1995 season as the Dodgers reached the playoffs for the first time since 1988, finishing first in True Average (.350), second in batting average, fourth in slugging percentage and WAR (6.0) and sixth in on-base percentage. Pitchers began to accord him a new level of respect. He hit .336/.422/.563 the following year, as his intentional walks increased from 10 to 21, and he walked 81 times in all, 35 more than his previous career high. He finished second in the NL MVP voting behind Ken Caminiti, and the Dodgers again made the playoffs but were swept in the first round. Lasorda was no longer at the helm by that point, having been forced into retirement due to a heart attack in late June.

The 1997 season was Piazza's best with the bat, a monster .362/.431/.638 campaign with 40 homers and 8.5 WAR, all career highs. His .369 True Average led the league again, while he was second in slugging, third in WAR (behind 2013 ballotmates Larry Walker and Craig Biggio) and the other slash categories. He finished second to Walker in the MVP voting.

By this point, the Dodgers were a team in transition, with owner Peter O'Malley hunting for a prospective buyer for the franchise. In January 1997, Piazza's agent, Dan Lozano, had been rebuffed in his attempt to get his client a six-year, $60 million deal on the grounds that such a decision should be left to the new owners. Piazza ended up signing a two-year, $15 million deal to cover the remainder of his pre-free agency years. After his big 1997, Lozano gave the team until Feb. 15 to hammer out a long-term extension; without one, his client was prepared to test free agency following the season. Lozano floated the idea of a seven-year, $100 million deal that would have been the largest in the sport at the time. The Dodgers were in the process of being sold to News Corporation (the parent company of Fox) and the deadline passed.

When Piazza complained about feeling "underappreciated" despite a team-record $8 million salary, fans turned against him. He rejected a six-year, $80 million offer in early April, and on May 14, was traded to the defending world champion Marlins as part of a seven-player blockbuster that brought Gary Sheffield and Bobby Bonilla to L.A. Piazza wore the teal for just five games before he was flipped to the Mets for a three-player package centered around outfielder Preston Wilson.

The Mets and Piazza turned out to be a strong fit, and he continued to hit, batting .348/.417/.607 for the remainder of the 1998 season. He signed a record-setting seven-year, $91 million deal in October 1998, and justified it by hitting .303/.361/.575 with 40 homers the following year as the Mets won 97 games and the NL wild card — their first playoff appearance since 1988 — advancing to the NLCS before being eliminated by the Braves.

With Piazza hitting .324/.398/.614 with 38 homers in 2000, the Mets would get even farther, winning their first NL pennant since 1986 and squaring off in the Subway Series against the Yankees. There Piazza would face Clemens, who had beaned him in an interleague game on July 8, causing a concussion that forced him to sit out the All-Star Game. Piazza had homered against Clemens in three straight games, and alleged that the beaning was intentional. In his first plate appearance of Game 2 of the World Series, he hit a foul ball and his bat splintered; adrenaline pumping, Clemens fielded the broken barrel and fired it across Piazza's path as he ran to first base, nearly hitting him. It certainly looked like an act of aggression; words were exchanged, Piazza walked towards the mound, benches emptied, tabloids had a field day. Piazza homered against reliever Jeff Nelson later that night, but the Mets lost the game and ultimately the series.

Piazza's production at the plate and behind it began to tail off slightly after the 2000 season, with his WARs declining from 4.9 in 2000 to 4.2 in 2001 to 2.7 in 2002, his age-33 season. He suffered his first major injury in 2003, a groin strain that cost him nearly three months; after averaging 143 games and 592 plate appearances for the previous seven years (while hitting a combined .320/.393/.583, by the way), he was limited to 68 games and 273 plate appearances that year.

Whispers of moving him to first base grew into talk show decibel-level shouts, and the Mets, in classic style, escalated tensions when manager Art Howe told the media that the team was going to ask Piazza to start working out at first base before actually asking the player. Eventually, Piazza's one appearance there while on his rehab assignment became national news. He played first base for the Mets in the second-to-last game of the regular season, and the following season, Howe decided to use him more at first than at catcher, but Piazza didn't take to the position; in 68 games there, he was nine or 10 runs below average according to three different defensive metrics, and the experiment was mercifully abandoned.

Piazza returned to full-time catching duty in 2005, but his final year in New York was interrupted by a hairline fracture in his left hand, and his numbers slipped. Now 37, he signed a one-year, $2 million deal with the Padres and despite playing half his games in Petco Park rebounded to .283/.342/.501 with 22 homers, his best numbers since 2003. In a memorable return to Shea Stadium on Aug. 9, he homered off Pedro Martinez and got a curtain call; a second homer off Martinez produced a more mixed reaction and the crowd nearly fainted when he drove a ball to the warning track in his final at-bat.

Despite his strong play, the Padres turned down an $8 million option for 2007, but Piazza got even more money from the A's, $8.5 million. He moved into a DH-only role, but missed nearly half the season after separating his shoulder diving into third base on May 2. Though some teams expressed interest in his services for the following year, he announced his retirement in May 2008.

In the end, Piazza finished his career holding the all-time record for home runs by a catcher (396, with his other 31 as a DH, first baseman or pinch-hitter). Among players who spent the majority of their careers as catchers and accumulated at least 5,000 plate appearances, his .308 batting average ranks third behind Mickey Cochrane (.320) and Bill Dickey (.313), his .377 OBP seventh and his .545 slugging percentage first, a whopping 54 points ahead of the number two man in that category, Javy Lopez.

In terms of True Average — which expresses a player's run production per out on a batting average scale after adjusting for park and league scoring levels, with .300 being very good — among that lot, his .313 is one point higher than Gene Tenace -- in over 2,220 more plate appearances -- and three points higher than Cochrane in 1,539 more plate appearances. Raise the bar to 7,000 PA and the next closest isn't either of those two but Dickey at .309, then Gabby Harnett at .302, Ernie Lombardi at .301 and Johnny Bench at .299. Factoring in playing time and productivity, Piazza has a very strong claim as the best-hitting catcher of all time.

As for his defense . . . it wasn't good, but the extent to which it was bad doesn't cost him all that much in the various metrics. Piazza threw out just 23 percent of would-be base thieves, seven percentage points below the league average during that time, but even so, that's just part of a catcher's job behind the plate. He led the league in passed balls a couple of times early in his career with 12, but as Sean Forman (of Baseball-Reference.com fame) showed in an award-winning presentation at the 2006 SABR convention, Piazza actually came up as one of the best in terms of pitch blocking, as defined by wild pitches and passed balls (somewhat arbitrarily distinguished between by official scorers), lessening the impact of his lousy throwing by about one-third, in terms of runs. All told, Baseball-Reference.com's Total Zone puts Piazza's work behind the plate at 61 runs below average, with his final four years of catching (2003-2006) at 16 below average according to the more sophisticated Defensive Runs Saved. Baseball Prospectus' numbers, which included an as-yet-unpublished arm rating (for throwing) put him around 40 runs below average for his career.

Relative to the excellence of his hitting, even the worst of those estimates doesn't cost him a lot. Despite his defense, Piazza is tied with Yogi Berra for fifth all-time in career WAR and JAWS among catchers behind Bench, Gary Carter, Ivan Rodriguez and Carlton Fisk; all of those players played in at least 208 more games. Piazza's peak WAR of 40.7 ranks third behind only Carter (46.5) and Bench (45.9), more than a win per year above the standard (32.0). That's not a borderline Hall of Famer, that's an inner circle one.

As with Jeff Bagwell, there exists among the BBWAA voting body a fair amount of suspicion that Piazza used performance-enhancing drugs, though he never tested positive, and wasn't named in the Mitchell Report or any other investigation. His absence from the latter is particularly noteworthy given that Mets clubhouse employee Kirk Radomski was at the epicenter of the report's allegations. Of the 89 players implicated by the report, 17 were Mets at one point, but Piazza's name was not among them.

In 2009, several writers such as Joel Sherman, Murray Chass and Jeff Pearlman wrote articles detailing their suspicions that Piazza had used, with more than one mentioning Piazza's back acne (a side effect of use). Pearlman's 2009 biography of Clemens, The Rocket Who Fell to Earth, quoted a supposedly off-the-record conversation in which Piazza said he used. All of the writers missed the fact that in the wake of Sports Illustrated's June 3, 2002 cover story on steroids, in which Caminiti admitted he had used, Piazza discussed his own past usage of androstenedione, which was still legal under both United States law and MLB policy, with the New York Times: "Piazza has said he briefly used androstenedione early in his career, stopping when he did not see a drastic change in his muscle mass. He said he had never used steroids because 'I hit the ball as far in high school as I do now.'"

We'll never know the veracity of that, or the extent to which andro may have helped Piazza's development. Indeed, there are no studies that tell us how much farther a player on this PED or that one can hit a ball, or how much they boost his production. What we do know is that andro (the supplement that was found inside Mark McGwire's locker during his 1998 home run binge and that Bagwell also admitted to using early in his career) was banned by the International Olympic Committee, which classified as an androgenic-anabolic steroid in 1997.

In June 2004, when baseball was in its first year of testing for steroids, it was added to Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act, which placed it in the same legal class as anabolic steroids as well as hydcrocodone (Vicodin), ketamine, synthetic THC, and other substances for which both accepted medical uses and the potential for abuse and dependence exist. Only at that point was it banned by baseball. What Piazza admitted to doing prior to that was legal, and quite possibly widespread among the player population.

Ultimately, some voters will use some combination of their suspicions and his earlier admission to keep Piazza off their ballots, but as I've said before, I do believe that the timing matters. There's no credible evidence to connect Piazza to using PEDs once they were banned by baseball. To penalize him for what came prior to the ban is to apply a retroactive morality that's inappropriate coming from the same writers who underreported the story of PEDs' encroachment on the game in the first place. To penalize him based on mere suspicion of wrongdoing without evidence is even lower.