JAWS and the 2013 Hall of Fame ballot: Bernie Williams

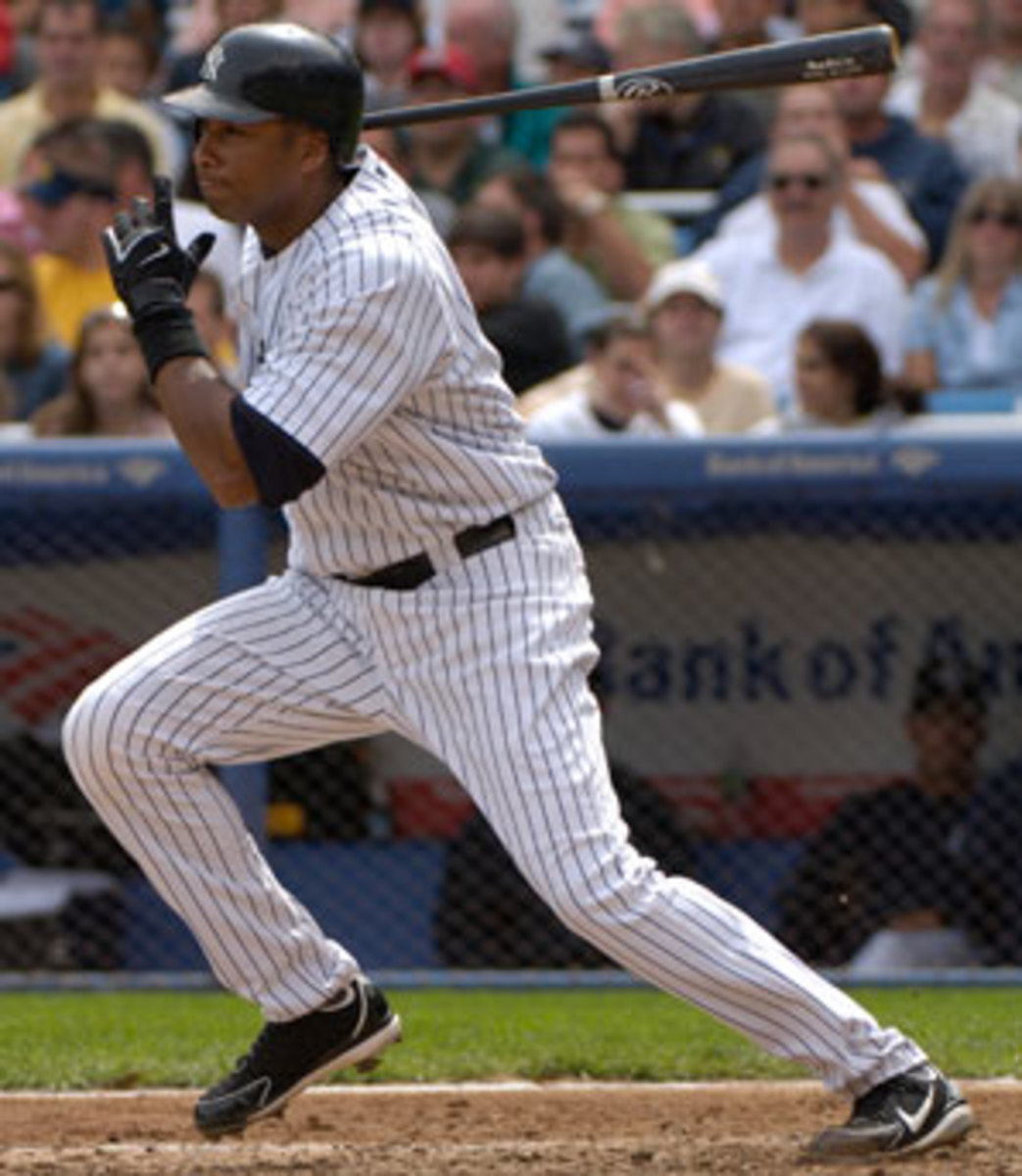

Bernie Williams would be the fourth Yankees centerfielder in the Hall of Fame, joining Earle Combs, Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle. (John Iacono/SI)

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2013 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here.

The turn-of-the-millennium dynasty in the Bronx began with Bernie Williams. As the Yankees emerged from a barren stretch of 13 seasons without a trip to the playoffs from 1982 to 1994, and a particularly abysmal stretch of four straight losing seasons from 1989 to 1992, their young switch-hitting centerfielder stood as a symbol for the franchise's resurgence. For too long, the Yankees had drafted poorly, traded away their homegrown talent for veterans, and signed pricey free agents to fill the gaps as part of George Steinbrenner's win-now directive.

With Steinbrenner banned by commissioner Fay Vincent in 1990, the Yankees' day-to-day baseball operations were put in the hands of general manager Gene Michael, allowing promising youngsters to develop unimpeded. Williams, who was signed out of Puerto Rico as a 17-year-old in 1985, reached the Yankees in July 1991, but split his first two seasons between the minors and majors.

{C}

When Michael traded centerfielder Roberto Kelly to the Reds for Paul O'Neill in November 1992 — a steal of a trade on its own merits, as it turned out — centerfield was freed up, and although Williams was not yet a finished product, he would eventually emerge as a key force in helping the Yankees recapture their glory.

Player | Career | Peak | JAWS | G | H | HR | SB | AVG | OBP | SLG | TAv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bernie Williams | 45.9 | 35.7 | 40.8 | 2076 | 2336 | 287 | 147 | .297 | .381 | .477 | .293 |

Avg HOF CF | 67.1 | 42.5 | 54.8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Williams put himself on the prospect map with a .335/.449/.487 season in the A-level Carolina League at age 19 in 1988, and when he held his own at Double-A Albany-Colonie the following year, he cracked Baseball America's Top 100 Prospects list at number 77. He struggled at Triple-A late in the season, however, and the Yankees sent him back to Double-A the next year, but he rose to number 11 on BA's list for 1991, and debuted in the majors on July 7 of that year, the last game before the All-Star break.

Williams hit just .238/.336/.350, and in the words of the New York Times' Buster Olney was "a natural target, bespectacled, awkward socially, quiet and introverted." Veteran outfielder and future convicted sex offender Mel Hall took aim at the rookie, taping "Mr. Zero" to the top of Williams' locker and interrupting him with "Zero, shut up," every time he tried to speak. Michael warned Hall that he would be traded or released if he didn't cease.

Hall departed for Japan and his eventual ignominy after the season, while Williams played just two games with the Yankees in April 1992 before being sent back to Triple-A until August. He secured his claim on the centerfield job with a .280/.354/.406 showing accompanied by solid defense over the season's final two months, then hit .268/.333/.400 in a full 1993 season with the Yankees who finished 88-74, their first winning season since 1988.

During the strike-shortened 1994 season, both he and the Yankees took steps forward; Williams batted .289/.384/.453 and finished with more walks than strikeouts for the first of five times in his career, and the team went an AL-best 70-43 before the players walked out in early August. He hit .307/.392/.487 with 18 homers in 1995 while helping the Yankees claim the AL wild card, including .359/.445/.536 from Aug. 1 onward, and stayed hot in the playoffs, hitting a searing .429/.571/.810 with a pair of homers — the first of 22 he would collect in October — in the team's five-game loss to the Mariners.

Building on that great finish, Williams blossomed into a star in 1996, hitting .305/.391/.535 with 29 homers and 17 steals, good for 6.1 WAR. Bolstered by the emergence of a few other homegrown players — Jeter, Andy Pettitte and Mariano Rivera — and led by new manager Joe Torre, the Yankees went on to win their first World Series since 1978. Williams was on fire for the first two rounds of the playoffs, hitting a combined 471/.548/1.000 with five homers, including a walkoff in Game 1 of the ALCS against the Orioles (the Jeffrey Maier game); he earned ALCS MVP honors.

The 1995 season was the first of eight straight in which Williams would post a True Average — a measure of a hitter's runs produced per plate appearance, adjusted for park and league scoring levels and expressed on a batting average scale — of .295 or better, the last seven of which were above .300. He hit a combined .321/.406/.531 during that eight-year period while averaging 4.9 WAR per season; his 39.5 WAR ranked 11th among position players during that span.

He earned All-Star honors from 1997-2001, Gold Gloves from 1997-2000 (though his defense was actually well into the red according to multiple metrics) and the 1998 AL batting title, with a .339 average. He received down-ballot MVP support in six of those seasons, though he never finished higher than seventh. The Yankees won five pennants (1996, 1998-2001) and four titles during that stretch. Following the 1998 season, Williams nearly defected to the Red Sox; only after a face-to-face meeting with Steinbrenner did the Yankees increase their offer from five years and $60 million (essentially what they were offering to Albert Belle at the time) to seven years and $87.5 million.

The Yankees won another pennant in 2003, but the 34-year-old Williams went into decline, hitting just .263/.367/.411 and missing a quarter of the season due to surgery to repair a meniscus; Hideki Matsui covered centerfield in his absence. Concerned about his flagging defense, the Yankees brought in free agent (and 2013 ballot-mate) Kenny Lofton the following season, and Williams spent 50 games as the team's DH. It didn't help his flagging bat; though his 22 homers were his most since 2001, his .262/.360/.435 made it clear that his skills were waning.

In 2005, he was again displaced by Matsui, this time as part of a shuffle that brought Robinson Cano up from the minors and sent Tony Womack to leftfield. The Yankees also tried Womack, rookie Bubba Crosby and a very green Melky Cabrera in center at various points before conceding that Williams was their best option; even so, his .249/.321/.367 suggested he was done. In January 2006, the Yankees signed free agent Johnny Damon, and bumped Williams — by then earning a base salary of $1.5 million plus incentives following the expiration of his big contract — to rightfield for the bulk of his playing time. Just prior to the July 31 deadline, they snared Bobby Abreu from the Phillies, turning Williams into a part-timer for the remainder of his days.

Williams, who turned 38 in September 2006, couldn't bring himself to officially retire, but wouldn't listen to overtures from teams besides the Yankees, who made it fairly clear they had no spot for him. A classically trained guitarist, he pursued a musical career, and stayed in shape long enough to participate in the 2009 World Baseball Classic for Puerto Rico. It would take him until February 2011 to acknowledge that his playing career was complete.

For as strong as his prime was, Williams winds up with the same JAWS score as Dale Murphy, albeit with a lower peak but a higher career value. Like Murphy, he had an outstanding, extended stretch of excellence bookended by mediocrity or worse; from 2003 onward, Williams hit a combined .263/.346/.412, and never embraced the types of roles — backing up first base and pinch-hitting — that can keep an aging player around long past his prime.

Williams was actually a full win below replacement (-1.0 WAR) during that stretch thanks to horrendous defense according to multiple metrics. In terms of Defensive Runs Saved, which is used in Baseball-Reference.com's version of WAR from 2003 onward: 17 runs below average in 2003, 20 below in 2004, 26 below in 2005, 11 below in 2006. That's 74 runs below average via DRS, about halfway between a more charitable −53 during that span via Total Zone (and −118 for his career) and a more brutal −93 via Ultimate Zone Rating. Baseball Prospectus' Fielding Runs Above Average puts him at just −15 for that 2003-2006 stretch, an outlier relative to the other three, and even there he came up 11.3 JAWS points shy in last year's evaluation of his candidacy.

Williams does have something beyond WAR going for him. His .275/.371/.480 line in 545 postseason plate appearances was quite good, essentially replicating his regular season performance against even tougher competition. Helped by the introduction of the three-round playoff system in 1995, he's all over the postseason leaderboard: first in RBIs, second in plate appearances, runs, hits, doubles, total bases and homers — behind Jeter in all but the latter category, where he trails Manny Ramirez. But even while crediting him for being an up-the-middle starter on pennant-winning teams, and for winning four Gold Gloves in years where he actually provided negative defensive value , his Hall of Fame Monitor score of 134 is hardly off the charts, and he never really made a dent in the MVP voting.

Ultimately, Bernie Williams doesn't have enough to justify a vote for the Hall of Fame, and after receiving just 9.6 percent of the vote last year, he's likely to fall off amid a larger crowd of qualified candidates. That may seem like a harsh judgment, but it does nothing to detract from his role as a crucial part of the Yankees' dynasty who will always be revered in the Bronx.