JAWS and the 2013 Hall of Fame ballot: Roger Clemens

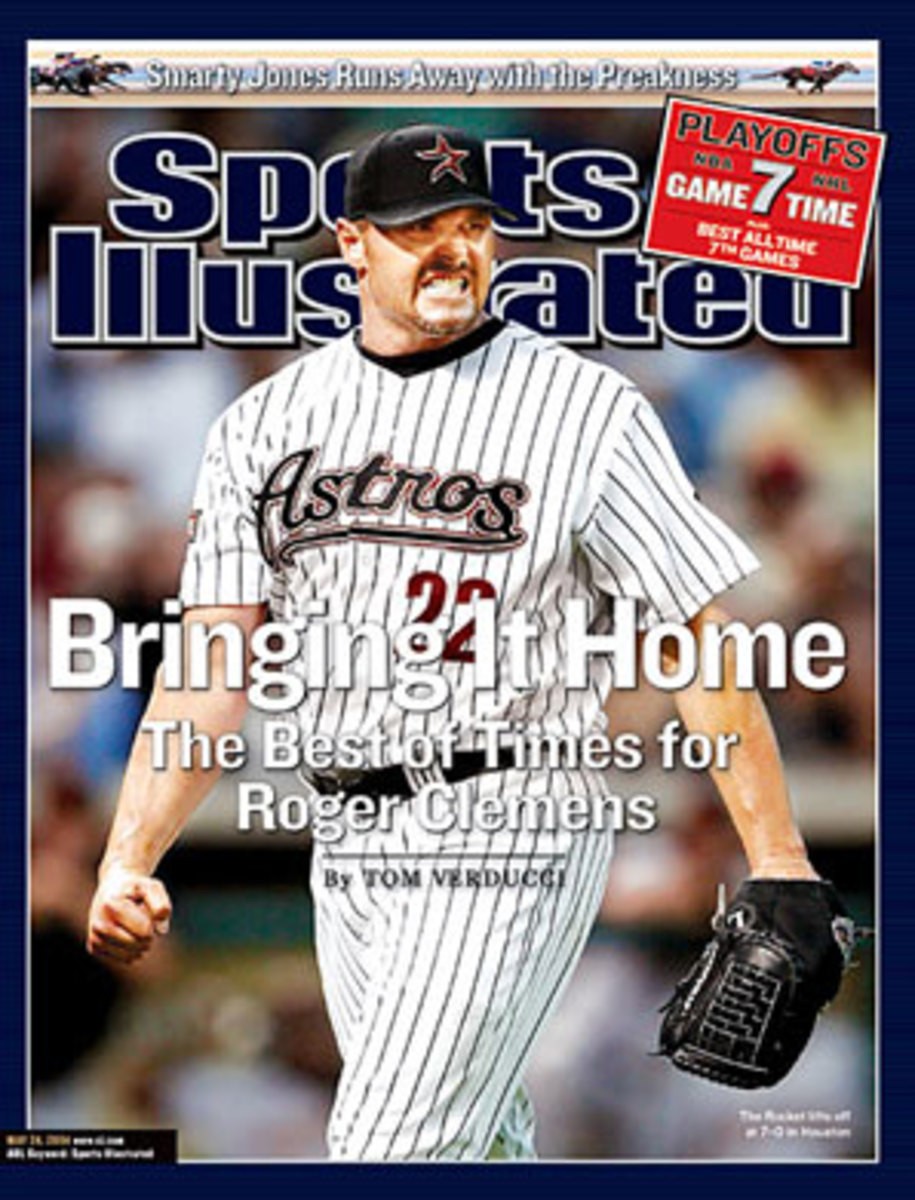

Roger Clemens showed no signs of slowing down in 2004, when he won his seventh and final Cy Young at age 42. (Jed Jacobsohn/Getty Images)

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2013 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here.

Roger Clemens has a reasonable claim as the greatest pitcher of all time. Cy Young and Christy Mathewson pitched during the Deadball Era, before the home run was a real threat. Those two, Walter Johnson and Pete Alexander, pitched while the color line was still in effect, barring some of the game's most talented players from participating. Sandy Koufax and Tom Seaver pitched when scoring levels were much lower, and pitchers were at a greater advantage. Koufax, Pedro Martinez and Randy Johnson didn't sustain their dominance for nearly as long. Greg Maddux didn't dominate hitters to nearly the same extent.

Clemens spent 24 years in the majors, and racked up a total of seven Cy Young awards, not to mention an MVP award. He won 354 games, led his leagues in the Triple Crown categories (wins, strikeouts, ERA) a total of 16 times, and helped his teams to six pennants and a pair of championships.

Alas, whatever claim he may have on such an exalted title is clouded by suspicions that he used performance-enhancing drugs. When those suspicions were voiced via the Mitchell Report in 2007, Clemens took the otherwise unprecedented step of challenging the findings via a Congressional hearing. He nearly painted himself into a legal corner and was subject to a high-profile trial for six counts of perjury, obstruction of justice and making false statements to Congress. After a mistrial in 2011, he was acquitted on all counts last June.

Despite the verdicts, the specter of PEDs isn't going to leave Clemens' case anytime soon, but on a Hall of Fame ballot that's full of hitters with connections to the drugs — Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, Rafael Palmeiro, Barry Bonds — it's worth remembering that the chemical arms race involved pitchers as well, leveling the playing field a lot more than some critics of the aforementioned sluggers would admit.

{C}

Pitcher | Career | Peak | JAWS | W | L | ERA | ERA+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Roger Clemens | 133.9 | 64.0 | 99.0 | 354 | 184 | 3.12 | 143 |

Avg HOF SP | 67.9 | 47.7 | 57.8 |

|

|

|

|

Contrary to legend, Clemens did not emerge whole from the Texas soil. He was born in Dayton, Ohio to parents who separated during his infancy, and he didn't move to Houston, Texas until high school in 1977. He not only pitched and played first base in high school, he also played defensive end on the football team, and center on the basketball team. After attending San Jacinto College North in 1981, he was drafted by the Mets in the 12th round, but he chose not to sign. Instead, he left for the University of Texas, earning All-America honors twice and pitching the Longhorns to a College World Series championship in 1983. The Red Sox made him the 19th pick of the 1983 draft. (Tim Belcher was chosen first overall, by the Twins, and Clemens' Texas teammate Calvin Schiraldi was chosen 27th by the Mets.)

Clemens debuted in the majors less than a year later, on May 15, 1984. Still just 21 years old, he had made a total of just 17 minor league starts across three levels, dominating all of them. He went 9-4 with a 4.32 ERA for the Red Sox, but more impressively, he struck out 8.5 hitters per nine of his 133-1/3 innings, a rate well above the official league leader (Mark Langston, 8.2 per nine) and the rest of the pack. Limited to just 15 starts the following year due to shoulder soreness, he was diagnosed with a torn labrum by a then-obscure orthopedist named Dr. James Andrews, who repaired the tear arthroscopically, a novel treatment for the time.

Eight months later, Clemens was back in action, and at 23, he put together his first outstanding season. In his fourth start, he set a major league record by striking out 20 Mariners; he didn't walk any, and allowed just three hits and one run. He wound up leading the AL in wins (24) and ERA (2.48) while ranking second in strikeouts (238) and WAR (8.6). That latter mark trailed only Milwaukee's Teddy Higuera, but Clemens' edge in the traditional numbers and his role in the Red Sox winning the AL East helped him capture not only his first Cy Young (unanimously, even) but also AL MVP honors. He made three good starts and two lousy ones in the postseason, throwing seven strong innings in Game 7 of the ALCS against the Angels and departing Game 6 of the World Series with a 3-2 lead and just six outs to go until the Red Sox won their first world championship since 1918. Alas, fate intervened in the form of sloppy relief work by Schiraldi (who had been traded to Boston in November 1985) and a groundball through Bill Buckner's legs.

Clemens followed up by winning 20 games, tossing seven shutouts among his 18 complete games (!) and racking up 9.1 WAR — totals which all led the league — in taking home a second Cy Young. He struck out a league-leading 291 and spun eight shutouts in 1988, helping the Sox to another AL East title. His 1989 was less notable (a garden-variety 5.3 WAR season), but he followed that up with the first of three straight ERA crowns in 1990; his 1.93 was less than half of the AL's 3.91 mark. He led the league with 10.3 WAR that year, but finished second to the A's Bob Welch in the Cy Young voting. Welch had gone 27-6 with a 2.95 ERA — more than a full run higher, in a much more pitcher-friendly park — in a season worth 2.7 WAR. The Red Sox won the AL East, but after throwing six shutout innings in Game 1 of the ALCS against the A's, Clemens was ejected in the second inning of Game 4 by home plate umpire Terry Cooney, who claimed that the pitcher cursed at him and called him "gutless." The ejection came in the midst of a three-run rally that would provide all of the offense the A's needed to complete a four-game sweep.

Clemens won his third Cy Young award in 1991, leading the league in innings (271 1/3), ERA (2.62), strikeouts (241) and WAR (7.1); the award made him the fifth pitcher to take home at least three Cys, after Koufax, Seaver, Jim Palmer and Steve Carlton, and the first to do so before age 30 (he was 29). He finished third in the voting in 1992 after leading again in ERA (2.41) and WAR (8.4).

No pitcher threw more innings than Clemens from 1986 to 1992 (1799-1/3), and no one was within 20 WAR of him during that span; Frank Viola's 35.5 ranked second to Clemens' 56.2. High mileage began taking its toll, however. Clemens averaged just 28 starts, 186 innings, 10 wins and 4.3 WAR over the next four seasons, about half the annual value he had generated in that previous seven-year stretch. He served stints on the disabled list in 1993 and 1995, for groin and shoulder injuries, respectively. His final year in Boston, 1996, was actually an outstanding one camouflaged by a 10-13 record and a 3.63 ERA (still a 139 ERA+); he threw 242-2/3 innings, his highest total since 1992, and led the league in strikeouts for the third time with 257. On September 18, in what proved to be his third-to-last start for the Sox, he tied his own major league record by striking out 20 Tigers, and again issued no walks. Despite his ability to consistently fool hitters, Boston GM Dan Duquette opted to let the Clemens depart for the Blue Jays via free agency, famously declaring that the 34-year-old was in "the twilight of his career."

The extent to which that statement fueled the final decade-plus of Clemens' career is an issue taken up further below, but sticking to the record as it unfolded at the time, the Rocket signed a three-year, $24.75 million deal, and followed with back-to-back seasons in which he not only won Cy Young awards but also Triple Crowns. His 1997 (21-7, 2.05 ERA, 292 strikeouts, 11.6 WAR) was by far the better of the two seasons, though his 7.8 WAR the following year led the league as well. His rebound caught the eye of Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, who had long coveted the now-36-year-old righty. On February 18, 1999, shortly after pitchers and catchers had reported to spring training, the defending world champion Yankees sent David Wells, Graeme Lloyd and Homer Bush to the Blue Jays in exchange for Clemens. Hampered by a hamstring injury, he spent three weeks on the disabled list and posted a 4.60 ERA during the regular season, but he fared better in the postseason, save for an early exit against the Red Sox in the ALCS; his 7-2/3 innings in Game 4 of the World Series against the Braves helped the Yankees complete a sweep to sew up their second straight championship.

Clemens' stint with the Yankees extended four more seasons. Though not as consistently dominant as he had been in Toronto, he helped the Joe Torre-led team win pennants in 2000, 2001 and 2003. Knocked around in two Division Series starts by the A's in 2000, he responded with a 15-strikeout, one-hit shutout of the Mariners in the ALCS, and eight innings of shutout ball in Game 2 of the World Series against the Mets, though that performance was overshadowed by his confrontation with Mike Piazza in which he hurled a broken bat barrel across the slugger's path as he ran down the first base line, with benches emptying and tabloids having a field day. Aided by outstanding run support (5.7 per game), he won a sixth Cy Young with a 20-3, 3.51 ERA season in 2001, though his 5.4 WAR ranked fourth. He struggled early in the postseason, totaling just 13-1/3 innings through his first three starts, but he hit his stride in the World Series against the Diamondbacks; with the Yankees trailing two games to none, he whiffed nine in seven strong innings while allowing just one run in Game 3, and struck out 10 in 6-2/3 innings in Game 7, though the Yankees ultimately lost. After a dud start in Game 7 of the 2003 ALCS against Boston, he had a strong outing against the Marlins in Game 4 of the World Series, but Torre's choice of Jeff Weaver in extra innings led to a defeat.

The 41-year-old Clemens initially retired after the 2003 season, but he was quickly lured back given the opportunity to join the Astros, who signed friend and former Yankees teammate Andy Pettitte. Pitching in the National League for the first time, he recovered some of his dominant form, winning his seventh and final Cy Young award in 2004 as he went 18-4 with a 2.98 ERA and 218 strikeouts, his highest total since 1998. He won yet another ERA crown with a 1.87 mark in 2005. After helping the Astros come within one win of a World Series berth in 2004 (his six-inning, four-run performance in Game 7 of the NLCS wasn't a career highlight), they won the pennant the following year. Alas, he had just one good postseason start out of three, plus a strong three-inning relief appearance that garnered a win in an 18-inning Division Series game against the Braves. He left the World Series opener after just two innings due to a hamstring strain, and the Astros were ultimately swept.

Convinced that his aging body wouldn't withstand the grind of another full season, Clemens dabbled with retirement for the next two years, sitting out spring training and making 19 starts with a 2.30 ERA for Houston in 2006, and 17 with a 4.18 ERA for the Yankees in 2007. Now 45 years old, any designs he had on furthering his career were put on hold when he was named in the Mitchell Report in December 2007. Based upon information obtained from Brian McNamee, who served as the Blue Jays' strength and conditioning coach in 1998, and then moved on to the Yankees in 2000, the report alleged that Clemens began using Winstrol (a steroid) in mid-1998 after learning about its benefits via teammate Jose Canseco, and that he used various steroids and human growth hormone in 2000 and 2001. McNamee, who also served as a personal trainer for Clemens and Pettitte in the 2001-2002 offseason, claimed to have performed multiple injections on Clemens, and to have stored the used syringes in empty beer cans. Pettitte testified that Clemens had told him about his use of HGH.

Clemens challenged the report, and two months later, had his day in front of Congress. Seeking to cast doubt on the report and on the testimonies of both Pettitte and McNamee, the Rocket and his counsel went a weak one-for-three, painting a picture of McNamee as a fairly disreputable character seeking to avoid jail time of his own. The Department of Justice opened a perjury investigation into Clemens' testimony, and in August 2010, he was charged with six felony counts of perjury, obstruction of justice, and making false statements to Congress. The case dragged on until June of 2012, when he was acquitted on all counts. Now 50 years old, he mounted a brief September comeback with the Sugar Land Skeeters of the Atlantic League, with son Koby catching him in two starts. Despite widespread speculation that he would pitch another game for the Astros — thereby bumping his Hall of Fame eligibility back another five years — he did no such thing.

There's little question Clemens has the numbers — traditional or sabermetric — for the Hall of Fame. His 354 wins rank ninth all-time, the second-highest total of the post-1960 expansion era behind Maddux's 355. His 4,672 strikeouts rank third behind Nolan Ryan and Randy Johnson. His seven Cy Young awards are two more than Johnson, three more than Carlton, and at least four more than any other pitcher. He led his leagues in wins four times, and placed in the top five seven other times. He led in ERA seven times, and placed in the top five on five other occasions. He led in K's four times, ranked second five times, and in the top five 16 times. His 133.9 career WAR ranks third behind Young (160.8) and Walter Johnson (157.8), and is nearly twice the total of the average Hall of Fame starter (67.9). The only other post World War II pitchers above 100 are Seaver (105.3) and Maddux (101.6). Clemens' 64.0 peak WAR ranks eighth, ahead of every pitcher whose career ended after 1930. His JAWS rank third behind Walter Johnson and Young; Seaver is the only postwar pitcher within 20 points of his 99.0. To borrow Bill James' praise of Rickey Henderson, cut Clemens in half and you'd have two Hall of Famers.

The PED allegations muddy the waters, though as I've stated before, the timing matters — at least to these eyes. The accounts contained in the Mitchell Report date to the time before MLB began testing players for PEDs or penalizing them, and Clemens is not known to have used them once they did. It's also worth noting that the findings of the report themselves didn't hold up in court, with the credibility of star witness McNamee a major problem. That's not to say that Clemens is as pure as the driven snow, by any means. He's a reflection of the era in which he pitched, and by the guidelines I've laid out in this series, I don't see anything in his case that puts him in the class of Rafaiel Palmeiro, the one candidate on the ballot who we know failed an MLB-administered drug test.

For those who want to play the "He was a Hall of Famer before he touched the stuff" game, Clemens notched 192 wins with a 3.06 ERA (144 ERA+) and 2,590 strikeouts with the Red Sox; his JAWS line for those years alone (77.9 total/58.3 peak/68.1 JAWS) would be above the Hall of Fame standard for starting pitchers, with a score between those of Pedro Martinez (80.5/56.3/68.3) and Bert Blyleven (89.3/46.8/68.0), good enough for 18th on the list. Note that such a ranking doesn't even include his Cy Young-winning 1997 performance with Toronto, around which there are no PED allegations.

Because of the PED connection, it's unlikely that Clemens will receive enough votes to gain first-ballot entry. But barring a smoking gun to cast further doubt on his accomplishments — or heaven forbid, yet another comeback — he's likely to get his plaque in Cooperstown at some point down the road.