Hall of Fame chances for Concepcion, Garvey, John, Parker, Quisenberry and Simmons (and Joe Torre, catcher)

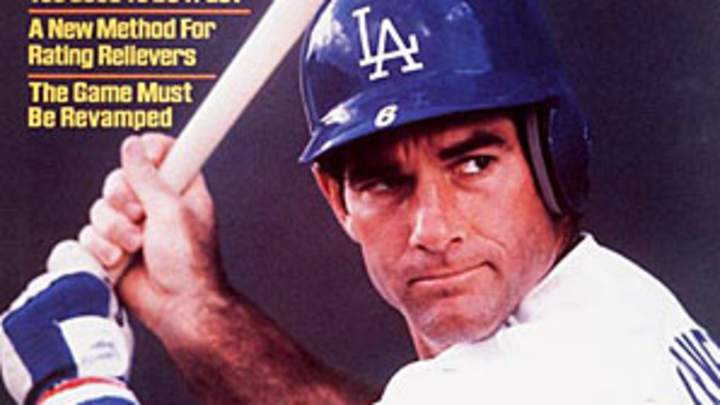

Steve Garvey made eight straight All-Star teams while with the Dodgers. (Heinz Kluetmeier/SI)

On Monday, the National Baseball Hall of Fame unveiled the 12-candidate slate for this year's Expansion Era ballot. At the upcoming meetings, a 16-member panel of Hall of Fame players and managers, writers and former executives will vote on those candidates, whose greatest contributions to the game came from 1973 onward -- an odd year to draw the line -- with the ones who receive 75 percent of the vote inducted into Cooperstown next summer.

My Strike Zone colleague Cliff Corcoran tackled the candidacies of the six non-players -- managers Bobby Cox, Tony La Russa, Billy Martin and Joe Torre, MLB Players Association executive director Marvin Miller and Yankees owner George Steinbrenner -- on Tuesday. I have some deeper thoughts the candidacies of Miller and Steinbrenner, written on the occasion of their respective passings, to add to the conversation, but I won't fill this space with them.

Torre's credentials as a player are germane to his case, however. He's on the ballot as a manager but voters are instructed to consider all of his contributions, and as is demonstrated below, he has a case no matter how you look at him. The other six players are: Dave Concepcion, Steve Garvey, Tommy John, Dave Parker, Dan Quisenberry and Ted Simmons.

As so often happens in these discussions, I prefer to use my JAWS system, which relies on Baseball-Reference.com's version of Wins Above Replacement to compare each candidate's value — career and peak (best seven years) to the players already in the Hall of Fame at his position. WAR accounts for each player's offensive and defensive contributions while adjusting for the wide variations in scoring levels that have occurred throughout baseball history, thus aiding considerably when it comes to cross-era comparisons. Here are the current averages at each position:

Position | Number | Career WAR | Peak WAR | JAWS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

SP | 58 | 66.7 | 46.7 | 56.7 |

RP | 5 | 38.6 | 27.1 | 32.8 |

C | 13 | 52.4 | 33.7 | 43.1 |

1B | 18 | 68.2 | 43.2 | 55.7 |

2B | 19 | 69.5 | 44.6 | 57.0 |

3B | 12 | 67.4 | 42.6 | 55.0 |

SS | 21 | 66.6 | 42.8 | 54.7 |

LF | 19 | 64.9 | 41.4 | 53.1 |

CF | 18 | 70.5 | 44.1 | 57.3 |

RF | 24 | 70.9 | 42.0 | 56.4 |

On to the candidates, who are presented in alphabetical order. I've written about most of them before over the years, but my shift from Baseball Prospectus' WARP to Baseball-Reference.com's WAR as the currency necessitates a fresh look.

Dave Concepcion, SS (40.0 career WAR/29.8 peak WAR/34.9 JAWS)

Concepcion spent his entire 19-year career (1970-1988) with the Reds and was the shortstop for one of the great dynasties in recent history, the Big Red Machine of the 1970s that won five division titles, four pennants and back-to-back World Series titles (1975 and '76) under Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson. Playing at a time when offensive contributions from shortstops were at their modern nadir, Concepcion wasn't much of a hitter, though he was hardly a total loss with the bat; he had six seasons as a regular and one as a part-timer with an OPS+ of 100 or better, and another where he was very close. For his career, he batted .267/.322/.357 while collecting 2,326 hits.

Better known for his fielding, Concepcion was a defensive marvel -- the pre-Ozzie Smith standard by which shortstops of the day were measured. He made nine All-Star teams (five as a starter), won five Gold Gloves and was something of a pioneer, perfecting a one-bounce throw off the Astroturf at Cincinnati's Riverfront Stadium and several other NL parks that increased his effective range. The Total Zone defensive system, which is derived from play-by-play accounts (no batted ball data was available at that time) credits him as being 71 runs above average from 1971-1983, and 52 runs above average for his career; four times he was in the league's top five in Defensive WAR, though he never led. That's a good-but-not-great total, much lower than the previous estimate -- which was based on Baseball Prospectus' Fielding Runs Above Average -- when he was up for election three years ago, and far removed from contemporaries Mark Belanger (+240) and Smith (+239).

That leaves Concepcion well short of the JAWS standard at the position, tied for 41st among all shortstops, just below more recent players such as Jimmy Rollins, Omar Vizquel and Rafael Furcal. He hit exceptionally well in the postseason (.297/.333/.455 in 112 PA) and scores 106 on the Bill James Hall of Fame Monitor, which credits players for things like seasons hitting .300, winning an MVP award, earning All-Star and Gold Glove honors, playing regularly for a championship team, leading the league in key categories and reaching certain milestones in a season or career. Though he was the only Expansion Era player to receive more than 50 percent of the vote last time around, he doesn't measure up as worthy here.

Steve Garvey, 1B (37.6/28.4/33.0)

A remarkably consistent and durable player during the prime of his 19-year career (1969-1987), Garvey was the most heralded member of the Dodgers' Longest Running Infield, earning All-Star honors every year from 1974-1981 and again in 1984 and '85, his second and third seasons with the Padres after departing Los Angeles via free agency. Stuck in a difficult hitters' park at Dodger Stadium, he topped 200 hits six times and 100 RBIs five times during that initial eight-year run, and won Gold Gloves in the first four of those years, all while maintaining perfectly coiffed hair.

Garvey was great in the postseason (.338/.361/.550 with 11 homers in 232 PA) and helped lead his teams to five World Series appearances. He also won a good share of hardware (1974 MVP, two-time All-Star Game MVP), played in 10 All-Star games and set the National League record for consecutive games played with 1,207 from Sept. 3, 1975, to July 29, 1983; that streak still ranks as the fourth-longest behind those of Cal Ripken, Lou Gehrig and Everett Scott.

Garvey finished his career with a .294/.329/.446 regular season line, 2,599 hits and 272 homers, numbers that appeared as though they might carry him to Cooperstown, but never got higher than the 42.6 percent of the vote he received in his third year on the ballot. A messy divorce, a pair of paternity suits and further legal problems tarnished his apple-pie image, which didn't help. From a JAWS standpoint, his real problem is his lack of walks en route to that low-ish OBP. As it is, he ranks just 50th among first basemen in JAWS, far below the standard on all three fronts.

Tommy John, SP (62.0/34.7/48.3)

Over the course of a 26-year major league career that ran from 1964 through 1989 (when he was 46 years old), the lefthanded John built a solid resume, highlighted by his 288 wins. Over the five-year period from 1977-1981, he placed in the top five in Cy Young voting three times (including being the runner-up in 1977 and '79), won 20 or more games three times and pitched in three World Series for the Dodgers and Yankees, though all on the losing side. His total of 4,710 1/3 innings ranks 20th all-time, and he's 26th in both wins and shutouts (46). Alas, he never led his leagues in any of the triple crown categories (wins, ERA and strikeouts), and never received more than 31.7 percent of the vote from the BBWAA in 15 years on their Hall of Fame ballot.

While the early versions of my system showed John to be slightly above the standard for enshrined starters, more recent iterations that account for his low strikeout rate (4.3 per nine) put him much farther way. He's currently 78th among starters in JAWS, far below the standard on both career and peak fronts.

That ranking has nothing to do with his pioneering role in the most famous sports medicine procedure of all time, the elbow ligament replacement surgery performed by Dr. Frank Jobe in 1974 that is now named for John. This past summer, the Hall of Fame honored both doctor and patient. John missed that entire '74 season amid an arduous 18-month rehab; had he not, he might have won 300 games -- essentially guaranteeing him enshrinement -- while getting a shot at another World Series with the Dodgers, who lost that year's Fall Classic to the A's. It's asking a bit much to apply such a large bonus for the surgery that he gets in; I wouldn't be opposed to it, but there are more deserving players on this ballot.

Dave Parker, RF (40.0/37.3/38.6)

The man nicknamed Cobra was a slugger with a cannon for an arm, and he compiled near-Hall of Fame numbers (.290/.339/.471, 121 OPS+, 2,712 hits, 339 homers) during his 19-year career (1973-1991), the first 11 of which were spent with the Pirates. He was in the spotlight often during that time via back-to-back batting titles in 1977 and '78, an MVP award in the latter year, All-Star MVP honors (check out this famous throw) and a world championship in '79 and Gold Gloves in all three of those seasons. In fact, he had a case as the best player in baseball during that span.

Alas, cocaine problems cost him some productivity toward the end of his time in Pittsburgh, and he was among several players who testified at the 1985 drug trials. Granted immunity for his testimony on the legal front, he received a suspended sentence from Commissioner Peter Ueberroth that allowed him to continue playing without suspension on the condition that he submit to random drug testing and donate part of his salary and some of his time to drug-related community service efforts.

By that point, Parker had resurrected his career with the Reds. In 1985, the best of his four years in Cincinnati, he hit .312/.365/.551, led the league with 125 RBIs, earned All-Star honors and was runner-up in the NL MVP voting. Though he couldn't match his Cincy renaissance, he was part of Oakland's 1988 pennant winners and 1989 world champions, and had his last big season with the Brewers in 1990. For all of that, Parker ranks just 35th among rightfielders in JAWS, about 30 wins shy on career score and five on peak. That's not good enough for Cooperstown.

Dan Quisenberry, RP (25.4/23.1/24.2)

Quisenberry was an eminently quotable sidearmer — "I found a delivery in my flaw," he famously quipped —who excelled during the heyday of the relief fireman. He led the AL in saves five times in a six-year span (1980-1985) for the Royals, the peak of a 12-year career that lasted from 1979-1990. He earned All-Star honors in three of those years, placed in the top three in the Cy Young voting for four straight seasons (third in '82 and '85, second in '83 and '84) and helped the Royals win the 1985 World Series. During that six-year stretch, he averaged 69 appearances and 121 innings a year, about twice the workload of today's closers. Though he put up a 2.76 ERA in his career, he wasn't dominant, striking out just 3.3 per nine, but he survived thanks to low walk and homer rates and an outstanding defense behind him that included Gold Glove winners Frank White and George Brett.

Quisenberry spent his last three years in Kansas City sharing the high-leverage duty, racking up just 21 more saves before being released and subsequently picked up by the Cardinals in mid-1988. After a solid 1989 season in a setup capacity in St. Louis, he made just five appearances for the Giants the following year before a torn rotator cuff led to his retirement. Unfortunately, he died of a brain tumor in 1998 at age 45.

Due to the brevity of his career, Quisenberry fell off the BBWAA ballot after one go-round, and falls short on all fronts when compared to the enshrined relievers, who themselves are a far cry from the value racked up by the starting pitchers in the Hall of Fame. In all, he ranks 19th among relievers, a couple hairs below Bruce Sutter but above Trevor Hoffman and the already-enshrined Rollie Fingers.

Ted Simmons deserves a longer look for Hall of Fame consideration. (Heinz Kluetmeier/SI)

Ted Simmons, C (50.2/34.7/42.5)

The 1970s was a bountiful era for outstanding catchers. Johnny Bench, Gary Carter and Carlton Fisk are all in the Hall of Fame and occupy three of the top four spots in the position's JAWS rankings. Simmons wasn't quite in their class, but he ranks 10th at the position, below six Hall of Famers plus Ivan Rodriguez, Mike Piazza and Torre (spoiler alert) and above the other seven, of whom only Roy Campanella was voted in by the BBWAA.

Simmons got just 3.7 percent of the vote in 1994, his only year on the BBWAA ballot. That may have had something to do with lingering resentment over the fact that in 1972, in the wake of former teammate Curt Flood's challenge to the Reserve Clause, he became the first playing holdout in baseball history, playing well into the season without a signed contract before the Cardinals gave in to his demands.

A six-time All-Star during his 13 seasons with St. Louis (1968-1980, though he played only seven games combined in the first two years), the switch-hitting Simmons was known more for his bat (.298/.366/.459, 118 OPS+, 2,472 hits, 248 homers) than his glove. He ranked among the league's top 10 in batting average six times, was in the top 10 in on-base or slugging percentage nine times and was among the top 10 in position player WAR five times. Behind the plate he was an adequate backstop, maligned during his era but essentially average via Total Zone (-8 runs career).

Simmons began to struggle shortly after being traded to the Brewers in a December 1980 blockbuster that also included Fingers. He hit just .260/.313/.395 and compiled only 5.3 WAR over his final eight seasons with Milwaukee and Atlanta, spending significant time at DH as well as first base and even third. He's one win above the peak average for catchers, but thanks to a whopping −2.6 WAR season in 1984, is 2.2 wins below the career standard and thus slightly short on JAWS. Still, I believe that being among a position's all-time top 10 is a sufficient reason to justify a vote. While conceding that Simmons is right on the borderline, I'd put him in based upon the evidence.

Joe Torre, C (57.4/37.3/47.4)

As mentioned above, Torre is on this ballot as a manager but voters are asked to consider his time as a player as well. Not that his case needs strengthening, but a glance at his 18 seasons from 1960-77 will only help his cause. A career .297/.365/.452 hitter (129 OPS+) with 2,342 hits and 252 homers, he spent more time at catcher (903 games) than any other position, but more time at first and third base combined (1,302 games) than behind the plate. Because JAWS slots a player where he accrued the most value, he winds up ranked among catchers, where he's sixth all-time, behind Bench, Carter, Rodriguez, Fisk, Piazza and Yogi Berra.

Torre was a nine-time All-Star while playing for the Braves (1960-1968), Cardinals (1969-1974) and Mets (1975-1977), with the first five of those honors coming while he worked behind the plate. He switched positions upon being traded to St. Louis -- straight up for future Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda -- in part because of Simmons; the two shared catching duties in 1970, the latter's rookie season, with Torre spending a bit less than half his time at the hot corner as well. After finishing second in the NL batting race that year, he won the NL batting title and MVP honors in 1971, his first season fully free of the tools of ignorance. That year, Torre hit .363/.421/.555 while collecting 230 hits and a league-leading 137 RBIs. In all, he had four top-10 finishes in batting average and offensive WAR, and seven in slugging or on-base percentage.

Traded to the Mets after the 1974 season, Torre became player-manager on May 31, 1977, but actually had just two pinch-hitting appearances in that capacity before calling it quits as a player. He went on to manage the Mets, Braves, Cardinals, Yankees and Dodgers for 29 seasons. While he won division titles in Atlanta and Los Angeles (twice) he's remembered best for the four world championships and six pennants he guided the Yankees to from 1996-2003, the beginning of a 12-season run in which he took New York to the postseason each time. Had Torre not managed as recently as 2010, his managerial career could have been considered as part of his case during previous election cycles, though he was not part of the 2011 Golden Era Committee go-round. With the entirety of his career now in focus, it's clear he's earned his plaque.

Jay Jaffe is a contributing baseball writer for SI.com and the author of the upcoming book The Cooperstown Casebook on the Baseball Hall of Fame.