Renteria, Ausmus, Williams and the new wave of first-time managers

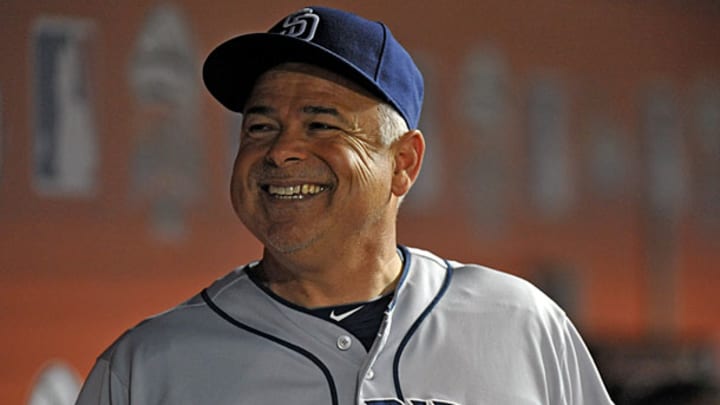

New Cubs skipper Rick Renteria has never managed in the majors or minors. (Steve Mitchell/Getty Images)

On Thursday, the Cubs officially hired Rick Renteria to be their new manager, succeeding Dale Sveum, who was fired after a 96-loss season. With Renteria's hiring, all five managerial jobs that opened since the end of the regular season have now been filled, four of them by men who have never before managed at the major league level: Bryan Price with the Reds, Brad Ausmus with the Tigers, Matt Williams with the Nationals and Renteria; only Lloyd McClendon, the new Mariners manager, has ever been a big league skipper before, and he was fired by the Pirates in the middle of the 2005 season.

This wave of new managers is part of a larger trend that dates back to the end of the 2011 season. Of the 17 times teams have changed managers since then (not including interim hires), the new hire has had less major league managerial experience than his predecessor 13 times. Of the four times that he did not, two of those successors (Bobby Valentine and Ozzie Guillen) were fired after a year on the job, suggesting those teams miscalculated significantly in their hirings. Twelve of those 17 changes have resulted in younger managers and 10 have been first-timers at the major league level.

Year | Team | Old | Age | Games | New | Age | Games |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2012 | Tony La Russa | 67 | 5,097 | Mike Matheny | 41 | 0 | |

2012 | Terry Francona | 52 | 1,944 | Bobby Valentine | 61 | 2,189 | |

2012 | Ozzie Guillen | 47 | 1,295 | Robin Ventura | 44 | 0 | |

2012 | Cubs | Mike Quade | 54 | 199 | Dale Sveum | 48 | 12 |

2012 | Marlins | Edwin Rodriguez* | 50 | 163 | Ozzie Guillen | 47 | 1,295 |

2013 | Red Sox | Bobby Valentine | 62 | 2,351 | John Farrell | 50 | 324 |

2013 | Jim Tracy | 56 | 1,736 | Walt Weiss | 49 | 0 | |

2013 | Marlins | Ozzie Guillen | 48 | 1,457 | Mike Redmond | 41 | 0 |

2013 | Manny Acta* | 43 | 890 | Terry Francona | 53 | 1,944 | |

2013 | Brad Mills* | 55 | 445 | Bo Porter | 40 | 0 | |

2013 | John Farrell | 50 | 324 | John Gibbons | 50 | 610 | |

Mid-2013 | Charlie Manuel | 69 | 1,826 | Ryne Sandberg | 53 | 0 | |

2014 | Tigers | Jim Leyland | 68 | 3,499 | Brad Ausmus | 44 | 0 |

2014 | Reds | Dusty Baker | 64 | 3,176 | Bryan Price | 51 | 0 |

2014 | Nationals | Davey Johnson | 70 | 2,445 | Matt Williams | 47 | 0 |

2014 | Mariners | Eric Wedge | 45 | 1,620 | Lloyd McClendon | 54 | 782 |

2014 | Cubs | Dale Sveum | 49 | 336 | Rick Renteria | 51 | 0 |

NOTE: "Year" denotes the start of the new manager's job, so the current crop is the class of 2014. Asterisks indicate that I've omitted interim managers from consideration. Most were for just a few games, though 80-year-old Jack McKeon guided the Marlins for the last 90 games of 2012; had I included that, the count for less experienced managers would have risen to 14.

The managers who were replaced averaged 56 years of age at the time of their departure, with six in their 60s or 70s, and five in their 40s. They had an average of 1,695 games under their belts, the equivalent of 10.5 seasons. Their successors averaged 48 years old, with just one older than 60 and nine in their 40s. They had 421 games of experience, the equivalent of 2.6 seasons.

From here, this trend reflects the evolution of the manager's job, and of the industry in general. Broadly speaking, the job of a manager has two major facets. The tactical one is more easily seen on a day-to-day basis, and it's the one on which fans and media tend to focus: bullpen usage patterns, platoons and defensive shifts, deployment of bunts, stolen bases and hit-and-runs. Those choices can be quantified and critiqued -- endlessly -- when things aren't going well.

VERDUCCI: Why a manager's role has changed, and what's really important about it now

The interpersonal area is less visible to the general public, and far less measurable. A manager's leadership ability and communication skills don't show up in the box scores, and often those qualities are ascribed after the fact, based upon the results. While the public does get a small sense of such things via a manager's media presence in pre- and postgame interviews, they are rarely privy to his actual strengths and weaknesses, the latter of which are far more likely to come to light via media reports — the manager feuding with a player or players, losing the clubhouse entirely or clashing with a general manager or owner. Think back to the case o the 2012 Red Sox and the anonymous players who were griping about Valentine amid Boston's 69-win debacle.

It's fair to say that both of those areas are undergoing an evolution, which helps to explain the trend that's resulting in younger skippers.

On the tactical side, statistical analysis is now part of virtually every front office, and while teams certainly don't use it to an equal degree, it's an available input, one to which younger managers may be more receptive than older ones.

For example, Williams expressed a level of comfort with advanced statistics in his introductory press conference last week, saying, "Old school is old school, and that's great… but if you don't get along with the times, bro, you better just step aside." While some raised an eyebrow when Williams professed that batting average with runners in scoring position is a metric he favors, it's worth noting that he brought along a Diamondbacks colleague, Mark Weidemaier, who has been hired as a seventh coach to oversee defensive positioning.

Meanwhile, Dusty Baker, who was fired by Cincinnati, seemed to have a perennial inability to build lineups that received acceptable on-base percentages out of the number two spot (.281 this year) despite the general emphasis in the stat throughout the game over the past decade. New skipper Bryan Price told the Cincinnati Enquirer's John Fay, "You have to use statistical analysis to understand certain themes and certain percentages. It’s a growing part of game."

Consider also Detroit, where recently retired Tigers skipper Jim Leyland expressed much different views on stats than his successor. When asked earlier this year about the statistics of likely AL Cy Young winner Max Scherzer -- whose 21-3 record had much to do with receiving the league's third-best run support -- Leyland said, "I don't believe in any of that stuff… I'm a baseball manager, not a statistician. I'm wasting my time talking about it." Ausmus, on the other hand, sounded far more open-minded when asked at his introductory press conference whether he embraced or rejected sabermetrics:

"I don't think you have to do either. I think there is some value to some of that. I can tell you that players do not like to be inundated with numbers...I think if you can take some of that statistical information and grind it down to a usable piece of information that you can hand [to] a player, that can be important. I don't think it has to be one school or another."

Obviously, Leyland found a great deal of success without relying on such inputs, though that doesn't mean they didn't have a role in how the front office shaped his team's roster. For example, sabermetrics tend to value pitchers with high strikeout rates, and the Tigers' staff set an all-time record for K rate at 8.8 per nine, well up from 6.6 per nine just three years ago, thanks in part to the trade acquisitions of Anibal Sanchez and Doug Fister over the past couple years.

The point isn't that the new managers are total Moneyball adherents who will manage by spreadsheet; the quotes I've excerpted above immediately followed with words about instincts and knowing one's personnel. The point is that these managers have expressed a willingness to use such concepts and to take direction from GMs with a desire to use such data in running their clubs.

As for the interpersonal area, its evolution has a longer arc. In general, a smaller age gap between a manager and his players makes for an easier ability to relate to the same experiences. For example, the playing careers of the old guard of managers dated back to a time before free agency, or at least when it was still a new thing that some teams fought against. Leyland never played at the major league level. Tony La Russa, who spent 33 years as a big-league manager before retiring after the 2011 season and being replaced by first-timer Mike Matheny, was done as a player before free-agency started. Ditto Charlie Manuel, who was fired in Philadelphia this past season and replaced by Ryne Sandberg in his first stint at the helm of a major league club. Davey Johnson, who just retired as Nationals manager, was at the end of his career when free agency was born, as were Bobby Valentine and Joe Torre.

CORCORAN: Hall of Fame chances for Bobby Cox, Tony La Russa and Joe Torre

That's not to say that those managers didn't adapt and have solid relationships with the free agents under them -- they wouldn't have lasted as long as they did otherwise -- but many of the newcomers have been through it themselves and have long accepted it as part of the landscape. They may have a better understanding of what it's like to be under the pressure of playing through a walk year, or of coming to a new team with a pricy contract.

Likewise, the newer managers have spent more time amid the growing internationalization of the sport at the major league level -- so much so that the Cubs made a point of seeking a bilingual one who could communicate more easily with Hispanic players including Starlin Castro and top prospects Javier Baez and Jorge Soler.

Obviously, some of these newcomers have inherited more difficult situations than others (something I'll explore in more detail on Friday). Renteria and McClendon could be years away from taking their teams to the playoffs, while Ausmus, Williams and Price are joining teams for whom the postseason is a fresher memory. All of them will be on the hook to live up to expectations, just as their predecessors were. Regardless of age, experience or philosophy, that part of the job never changes.