Most Valuable Player Awards preview: McCutchen vs. Goldschmidt, Trout vs. Cabrera

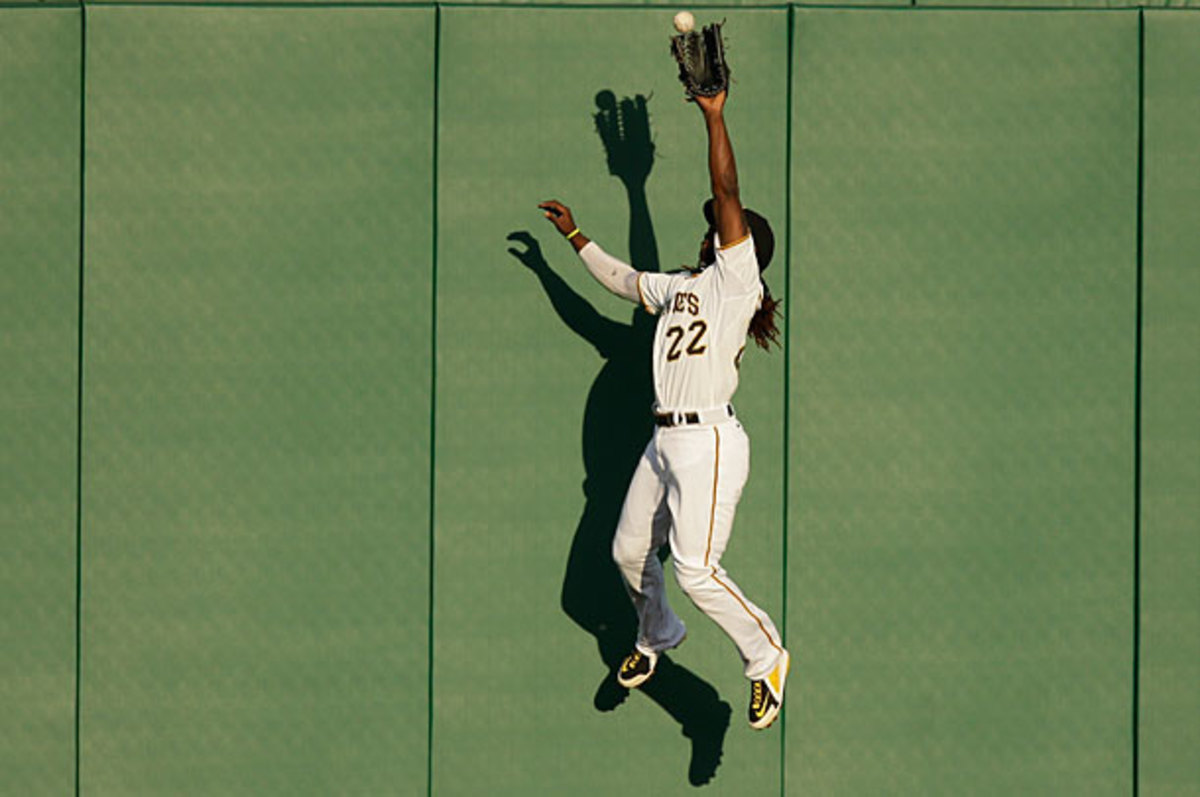

Andrew McCutchen's strong play in centerfield gives his just enough of an edge in the NL MVP race. (Gene J. Puskar/AP)

Awards Week draws to a close Thursday night with the announcements of the winners of the Most Valuable Player awards in each league. While the choices for Rookie of the Year (Jose Fernandez in the National League and Wil Myers in the American League) and especially Cy Young (NL: Clayton Kershaw; AL: Max Scherzer) were fairly obvious, there is no such clear-cut favorite for MVP in either league.

In the American League, we have a re-staging of last year's Mike Trout vs. Miguel Cabrera controversy, with progressive analysts again favoring Trout and traditionalists favoring likely winner Cabrera. The debate in the National League comes down to two similarly productive all-around players, Andrew McCutchen and Paul Goldschmidt. Buckle up.

Note: League leaders are in bold, major league leaders in bold and italics. Winners will be announced live on MLB Network starting at 6 p.m. ET.

National League

Paul Goldschmidt, 1B, Diamondbacks

Season Stats: .302/.401/.551, 36 HR, 125 RBI, 103 R, 710 PA, 15 SB (68%)

Andrew McCutchen, CF, Pirates

Season Stats: .317/.404/.508, 21 HR, 84 RBI, 97 R, 674 PA, 27 SB (73%)

In both leagues the MVP race effectively boils down to the best hitter (Goldschmidt and Cabrera) against the best all-around player (McCutchen and Trout). In such cases, I find it easier to make a comparison after folding each players' stolen bases into his batting line. I do this by adding their number of steals to their total bases and recalculating their slugging percentages, and then by deducting their times caught stealing from their times on base to recalculate their on-base percentages. Doing that yields these slash lines for the two NL players above:

Goldschmidt: .302/.395/.576

McCutchen: .317/.395/.554

What you see there are identical on-base percentages, with a larger portion of McCutchen's comprised of hits, which are more valuable (though less predictive) than walks. You can see something similar in their raw slash lines above, but factoring in the steals closes the gap in slugging percentage to 22 points.

What is not shown above is that Pittsburgh's PNC Park was the hardest place in the major leagues this season for a righthanded hitter (which McCutchen is) to hit a home run. The Bill James Handbook gave PNC a park factor of 61 for righthanded home runs this year, while FanGraphs gave it an 88. Both rated Arizona's Chase Field as a tick above average for righthanded (which Goldschmidt is as well) home runs. Credit McCutchen with just three more homers (he did hit three more longballs on the road than at home this year) and his steals-enhanced slugging percentage above jumps up to .574, just two points shy of Goldschmidt's. All of which is to say that, when factoring stolen bases and park factors into their battling lines, Goldschmidt and McCutchen were effectively equals on offense this season.

That leaves it to defense to break the tie, and while Goldschmidt was an elite defensive first baseman in 2013, winning the Gold Glove and Fielding Bible award (both of which were announced after the MVP votes were submitted), McCutchen, by simple virtue of being an above-average centerfielder, was more valuable with the glove. Similarly, the level of offensive production that McCutchen and Goldschmidt contributed to their teams this season is much harder to find in a centerfielder than in a first baseman.

Season Stats: .319/.359/.477, 12 HR, 80 RBI, 68 R, 541 PA

It's difficult to argue that Molina was the most valuable Cardinal, never mind the most valuable player in the entire National League. Matt Carpenter hit .318/.392/.481 in 717 plate appearances while leading the majors in runs, hits and doubles. As a second baseman, Carpenter also played on the left side of the defensive spectrum, ably filling a position at which he had made just two previous starts in his professional career and providing defensive flexibility for St. Louis by also making starts at third base (24), first base (1) and rightfield (1).

The case for Molina rests on his performance behind the plate. He excels at every aspect of receiving, from pitch blocking and framing to throwing out baserunners, but exactly how much those abilities are worth -- and how much, if any, credit he deserves for the overall ability of the St. Louis pitchers to prevent runs -- is difficult to discern. As a result, analysts such as myself who prefer to deal with objective measures of performance may undervalue Molina, while others, who freely assign value based on subjective observation without regard for what is measurable likely overstate his value -- possibly by a great deal.

Recent research has revealed that pitch framing is a repeatable skill, one at which Molina is proficient, and can be worth as much as two wins above replacement per season. Of course, the impact of that skill would be on pitcher performance, and past studies of Catcher's ERA have suggested that backstops do not have a discernible and repeatable impact on the performance of their pitchers. Those two findings would seem to be in conflict, but consider that only the catchers at the most extreme ends of the pitch-framing spectrum can impact pitcher performance by two wins, and that two wins is roughly equivalent to 20 runs. Molina caught 1,115 1/3 innings in 2013. Twenty runs factored into that many innings is roughly 0.16 points of ERA, which, again, represents the high end of catcher impact via framing alone.

Unfortunately, we don't have the actual data for Molina's 2013 season, but in the landmark study done by Mike Fast for Baseball Prospectus, just two catchers reached the 20-run mark in the five seasons from 2007 to 2011. Molina's average over that span was 7.4 runs, or less than one win. As for pitch calling, it's all well and good to call for a fastball high and tight or a slider away, but if the pitcher can't execute or locate that pitch, it could just as easily be ball four or a home run as a strike. Therefore, it seems misguided to credit a catcher for his pitch calling, particularly in light of the research on Catcher's ERA.

The other facets of Molina's defense -- specifically pitch blocking, controlling the running game and fielding bunts -- are factored into the Fielding Bible's Defensive Runs Saved, which is the defensive component of Baseball-Reference's Wins Above Replacement (bWAR). DRS also has an "adjusted earned runs saved" component that gives catchers partial credit for their Catcher's ERAs, and bWAR itself contains a position adjustment that credits catchers for simply filling the most difficult position on the diamond. Molina's raw DRS is 12 runs, or roughly 1.2 wins.

Given all of that, it seems fair to say that the 2.1 defensive bWAR credited to Molina -- the seventh-best total in the league and one that includes the defensive adjustment -- represents an extremely favorable objective evaluation of his work behind the plate in 2013. Even if we add an extra win for framing, Molina still falls short of Goldschmidt and McCutchen in total bWAR (6.7, compared to Goldschmidt's 7.1 and McCutchen's 8.2). I don't believe that the MVP should be the "most WAR" award (that ship has sailed, anyway, as this year's NL bWAR leader, the Brewers' Carlos Gomez at 8.4, is not among the finalists), but it seems clear that Molina's deficit in bWAR reflects a very real deficit in actual value relative to his fellow finalists.

Who should win: McCutchen

Who will win: McCutchen

American League

Once again, the AL MVP race comes down to Mike Trout (left) and Miguel Cabrera. (Paul Sancya/AP)

Chris Davis, 1B, Orioles

Season Stats: .286/.370/.634, 53 HR, 138 RBI, 103 R, 673 PA

I'm listing Davis out of alphabetical order here because he's really an afterthought in the debate between Cabrera and Trout, though he may pick up a stray first-place vote or two because he led the majors in two of three Triple Crown categories, set an Orioles team record with 53 home runs and helped Baltimore to another winning season. However, the last should be irrelevant (as I discuss below), Davis is a sub-par defensive first baseman competing against two players further left on the defensive spectrum, and even without factoring in team or defense, his raw offensive output was less impressive than that of either Cabrera or Trout.

Miguel Cabrera, 3B, Tigers

Season Stats: .348/.442/.636, 44 HR, 137 RBI, 103 R, 652 PA

Mike Trout, CF, Angels

Season Stats: .323/.432/.557, 27 HR, 97 RBI, 109 R, 716 PA, 33 SB (83%)

Once again, let's take a look at those batting lines with stolen bases added to the slugging and times caught stealing deducted from the on-base percentage:

Cabrera: .348/.442/.641

Trout: .323/.426/.613

Isolate their slugging by subtracting batting average from slugging percentage and you get 293 for Cabrera and 290 for Trout. Isolate their on-base skills by subtracting batting average from OBP and you get 94 for Cabrera and 103 for Trout.

Now consider this: Per the Bill James Handbook, the park factor for righthanded batting average at Comerica Park this season was 105, while the park factor for righthanded batting average at Angel Stadium was 96. In other words, Cabrera got about a five percent boost at his ballpark and Trout took a four percent hit at his. Shave five percent off Cabrera's home batting average and you get .339, still above his road mark this season.Give Trout a four-percent boost in his home average, and you get .329. Add those ISO totals (293 SLG and 94 OBP for Cabrera; 290 SLG and 103 OBP for Trout) back on to those adjusted batting averages and you get this:

Cabrera: .339/.433/.632

Trout: .329/.432/.619

Suddenly the on-base percentages are effectively even and the slugging is within 13 points. Depending on your source, Angel Stadium was a tougher place for righthanded hitters to hit home runs than Comerica Park this year (that has been true historically, and FanGraphs says the same was true this past year, but the Bill James Handbook has the two parks even in that regard in 2013). Either way, Trout closes some of that tiny gap by having played in nine more games and come to the plate 64 more times than Cabrera, and more than makes up for the rest of it with his superiority in the field. That's both because an average centerfielder (Trout started 108 games in center this year) is inherently more valuable defensively than an average third baseman, and because the fielding metrics all agree that Cabrera was awful at third base this year: DRS, Ultimate Zone Rating and Fielding Runs Above Average all rate him more than a win below average at the hot corner. (For the record, the advanced defensive metrics were generally unimpressed with Trout's glovework, though his total WAR easily outpaced Cabrera's, 9.2 to 7.2.)

So, once again, Trout was better than Cabrera, and once again, he was the best player in baseball. Yet once again, he won't win his league's Most Valuable Player award. Last year it was because traditionalists could point to Cabrera's Triple Crown, the first in 45 years, to justify their vote. This time it will be because of the performance of Trout's teammates.

It was a factor last year, too, when Trout's Angels won 89 games but missed the playoffs while Cabrera's 88-win Tigers captured the division title. This year, however, Detroit won 93 games and Los Angeles only won 78. That, more than any other factor, seems likely to again deliver the AL MVP to the wrong player.

This is faulty reasoning, at best. The MVP is an individual award that should be decided by individual performance. What the other 24 men on a candidate's team do should not impact the vote because their performances do not impact the candidate's value. That value is absolute, regardless of whether or not the team around him is a 60-win team or a 90-win team. The idea of performance mattering more when it comes under pressure is malarkey, as well. Some players lose focus in a sub-.500 season but thrive under the pressure of a pennant race, while for others the opposite is true.

Most importantly, the rules given to voters every year explicitly define value as the quality of a player's offense and defense. It's right there on the Baseball Writers' Association of America website (emphasis added):

The MVP need not come from a division winner or other playoff qualifier.

The rules of the voting remain the same as they were written on the first ballot in 1931:

1. Actual value of a player to his team,

that is, strength of offense and defense.

As I explained to Brian Kenny on MLB Network's Clubhouse Confidential last week, "that is" means "defined as." The MVP should be decided purely on the strength of a player's offense and defense with secondary consideration given to his playing time (which is number-two on the list in the rules, "number of games played"). That's it, and that's all. For the second year in a row, the AL MVP should be Mike Trout. But it won't be.

Who should win: Trout

Who will win: