JAWS and the 2014 Hall of Fame ballot: Greg Maddux

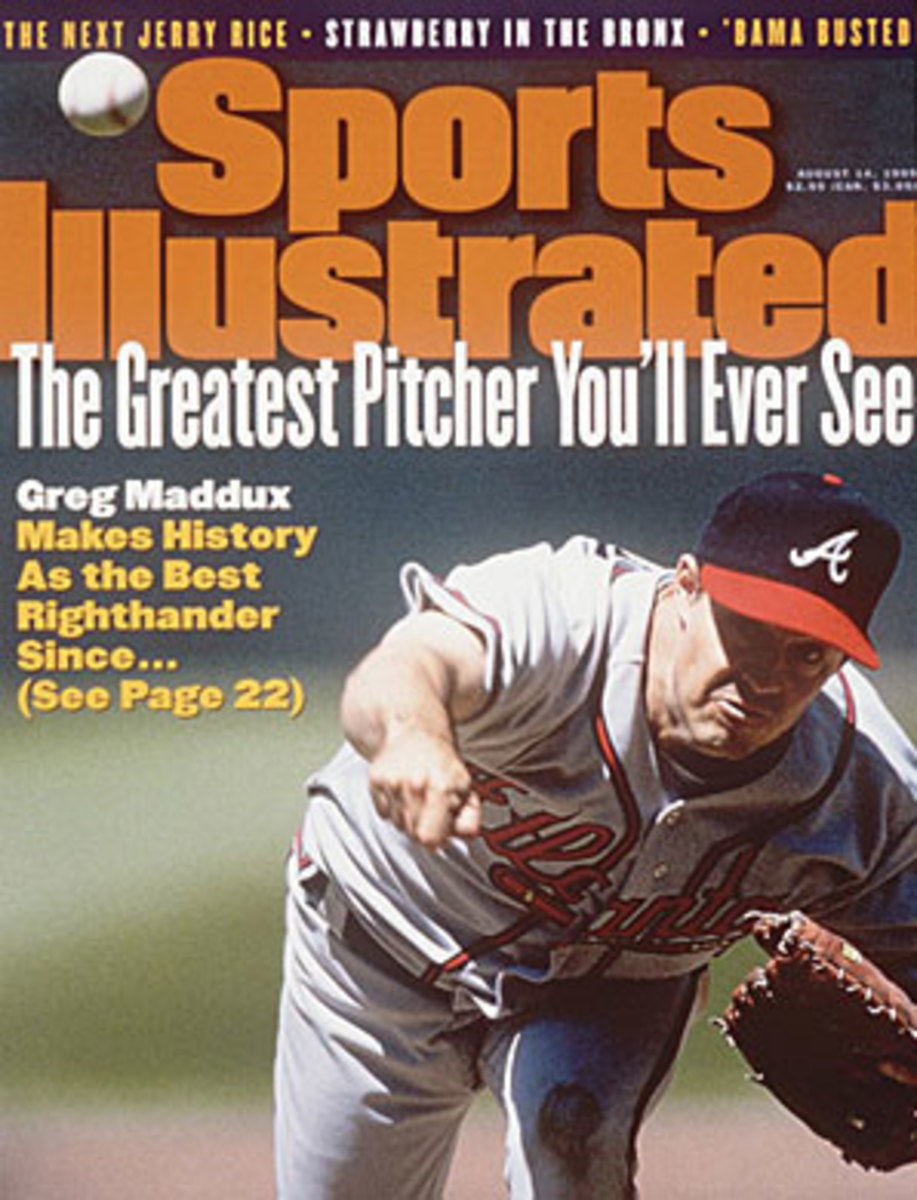

Greg Maddux has a chance to become the first unanimous selection to the Hall of Fame. (Richard Mackson/SI)

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2014 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here. For the schedule, see here.

In the discussions I've had regarding this year's Hall of Fame ballot, the crowded field of candidates and the ways that the process might be improved, I've heard one sentiment repeatedly: "Anybody who doesn't vote for Greg Maddux ought to have his ballot revoked."

Given the body of work in question, it's not hard to see why. Maddux's 355 wins are the most of any righthanded pitcher since World War II. He won four Cy Youngs, led the NL in ERA four times, made eight All-Star teams and helped his teams to the playoffs 13 times, including a run of 10 straight trips with the Braves from 1993-2003 (excepting the 1994 strike season). He was durable, too; in his 23-year career, he reached 190 innings 21 times (tied with Don Sutton for the all-time lead) and he did it consecutively, even topping 200 in the strike-shortened 1994 and '95 seasons. Only once did he spend time on the disabled list. Most impressively, he excelled at a time when scoring was at its highest level since the 1920s and '30s, making him the rare pitcher to stand out in an era typified by musclebound sluggers.

Unlike Roger Clemens, Maddux didn't succeed due to mid-90s velocity; his fastball reached 93 mph in his early years, but generally ranged in the mid-to-high 80s in his prime. Instead, it was his exceptional command of a wide array of pitches, an ability to avoid hard contact and a cerebral approach founded in an understanding of effective velocity — the combination of speed and location — that made him great. Rob Neyer hailed him as "the smartest pitcher who ever lived" in the middle of his career, and the tag stuck, though longtime Braves pitching coach Leo Mazzone later explained the source of Maddux's genius: "He always told me, 'When you can throw your fastball where you want, when you want, it's amazing how smart you can be.'"

Because he has no known connection to performance-enhancing drugs at a time when the electorate is dragging its collective feet over those who do, Maddux is virtually assured of gaining first-ballot entry in 2014. Under normal circumstances, he might be expected to challenge Tom Seaver's all-time high of 98.84 percent of the vote, set in 1992, but between the crowd of qualified candidates and the blank ballot brigade (which cast five empty votes last year), it's not hard to imagine him falling short of that lofty rate — less due to any personal vendetta than to the greater impact that vote might have elsewhere, as I explain below.

That shouldn't obscure the larger point: Maddux is a lock to get in, guaranteeing that the BBWAA won't achieve a back-to-back shutout after admitting no one last year.

Pitcher | Career | Peak | JAWS | W | L | ERA | ERA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Greg Maddux | 106.8 | 56.3 | 81.6 | 355 | 227 | 3.16 | 132 |

Avg HOF SP | 72.6 | 50.2 | 61.4 |

Born in San Angelo, Texas, Greg Maddux was the youngest of three children fathered by an Air Force officer. He was four and a half years younger than brother Mike, who himself spent 15 years (1986-2000) in the majors and today is the pitching coach of the Rangers. Both boys spent much of their childhoods in Madrid, Spain, and then Las Vegas, Nevada. In Vegas, Mike began taking informal instruction from retired major league scout Ralph "Rusty" Medar, and Greg tagged along; soon he too caught the scout's attention. Recalled their father, Dave, for a 1995 Sports Illustrated feature by Tom Verducci, "The first time Greg threw, Mr. Medar said, I don't know where the boy got those mechanics, but let me tell you this: Don't you let anybody change those mechanics. He's going to be something."

Maddux learned a changeup from Medar, which helped him compensate for his lack of size (5-foot-11, 150 pounds when he graduated high school) and velocity. Though agent Scott Boras advised him to go to college, Maddux nonetheless signed with the Cubs when he was drafted in the second round in 1984, receiving an $85,000 bonus. Despite a middling minor league strikeout rate, he climbed the ladder quickly and debuted in the majors on Sept. 2, 1986, three months after his brother. In an epic game against the Astros that was started by Houston's Nolan Ryan and Chicago's Jamie Moyer — two pitchers whose careers combined to span an epoch from 1966 to 2012 — Maddux entered in the 17th inning as a pinch-runner for catcher Jody Davis and was the losing pitcher after surrendering a solo homer to Billy Hatcher in the 18th.

Maddux made five starts that month, then broke camp in the Cubs' rotation the following spring. Still just 21 years old, he was knocked around mercilessly, at one point getting sent back to Triple A and finishing the year 6-14 with a 5.61 ERA. He quickly turned the corner, however, beginning his 1988 season with a three-hit shutout of the Braves, earning All-Star honors for the first time and ending up 18-8 with a 3.18 ERA in 249 innings; his 5.2 WAR for the season ranked fourth among NL pitchers. In 1989, he finished third in the Cy Young voting and fifth in WAR (5.0) while helping the Cubs win the NL East, going 19-12 with a 2.95 ERA in 238 1/3 innings.

After solid seasons in 1990 and '91 — the latter of which saw him lead the league in innings pitched for the first of five straight years at 263 — Maddux won his first Cy Young in 1992 on the strength of a 20-11 record and 2.18 ERA in 268 frames. He gave up just seven homers in that span, leading the league in home run rate (0.2 per nine) for the first of four times and in WAR (9.2) for the first of three times. He beat out future teammate Tom Glavine for the Cy Young, getting 20 of 24 first-place votes.

Maddux joined forces with Glavine that winter, signing a five-year, $28 million deal with the Braves. Reportedly, he spurned a five-year, $34 million offer from the Yankees, whose general manager Gene Michael had managed him with the Cubs in 1986 and '87. He's also said to have passed up a $27.5 million take-it-or-leave-it offer from the Cubs, who gave him just four days to consider and told him it was too late by the time he called.

In Atlanta, the 27-year-old Maddux joined a team that had won back-to-back pennants in 1991 and '92, and a rotation that included 1991 Cy Young winner Glavine as well as Steve Avery (1991 NLCS MVP), John Smoltz (1992 NLCS MVP) and former first-round pick Pete Smith, who had gone 7-0 with a 2.05 ERA in a late-1992 stint; an April 1993 Sports Illustrated feature by Steve Rushin hailed them as "Five Aces." Smith was a dud, going at 4-8 with a 4.37 ERA that year, but the team as a whole won a franchise-record 104 games and its third straight NL West flag — yes, prior to 1994 realignment, Major League Baseball somehow reckoned Atlanta was further west than St. Louis or Chicago — before being eliminated by the Phillies in the NLCS.

Maddux led the league in ERA for the first time (2.36) that year and won 20 games and his second straight Cy Young, though his 5.8 WAR was miles behind the 9.3 of league-leader Jose Rijo. In the strike-shortened 1994 season, Maddux led the league with a microscopic 1.56 ERA and 8.5 WAR and was a unanimous selection for the Cy Young award. That made him the first pitcher ever to win three straight Cys; his 2.08 ERA over that span was nearly half the major league average of 4.11.

Maddux had the best year of his career in 1995 while helping the Braves win their first of 11 straight NL East titles. Though limited to 209 2/3 innings by the shortened season, he lead the league in that category as well as wins (19), ERA (1.63), complete games (10), shutouts (3), home run rate (0.3 per nine), walk rate (1.0 per nine), WHIP (0.811) , strikeout-to-walk ratio (7.9) and WAR (9.7). Not only would most of those marks hold up as career bests, but he again was a unanimous winner for the Cy Young, making him the award's second four-time winner after Steve Carlton, and he placed third in the NL MVP voting, the highest he would ever finish. In five postseason starts, he posted a 2.84 ERA, most notably two-hitting the Indians in Game 1 of the World Series. While he lost Game 5, the Braves won their first world championship since 1957 — the only one they would win under manager Bobby Cox — behind Glavine's one-hit shutout in Game 6.

That October, The Sporting News' Michael P. Geffner described the four-time Cy Young winner's arsenal and approach in a cover story that captures Peak Maddux (hat-tip to The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers, which included part of this passage):

[T]ypically, it was a performance fully appreciated only after it was over, when, all at once, you are suddenly struck by the staggering number of soft outs he induced: inning after easy inning of squibbers off the end of the bat; dribblers off the handle; check-swing grounders; half-swing popups; and bat-freezing called third strikes. And, maybe even more striking, is the way he seems to accomplish this without so much as breaking a sweat, so simply, so undramatically, doing nothing more than merely mixing average, slightly above-average, and slightly below-average pitches: an 82- to 86-mph fastball (on the slow radar gun) that he throws 70 percent of the time, a decent slider, a circle-change (his strikeout pitch), a cutter (a breaking fastball to back off lefthanded hitters), and a big, slow nothing of a curve.

But don't be fooled: The mixture is perfectly calculated and unrelentingly diabolical, striking stunningly, pitch after pitch, at the hitter's weakest points, straight for the kill -- outside corner, inside corner, down and away. And always at different speeds and from that same stripped-down, monotonous delivery. Everything moving dizzily away from the center of the plate. Until the poor hitter can't even see straight. Until he's on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

(NOTE: For an analysis of Maddux's delivery complete with visuals, see Baseball Prospectus' Doug Thorburn.)

Maddux helped the Braves return to the World Series in 1996, but his performance took a step back, as his ERA "skyrocketed" to 2.72. That was still good for second in the league, and he led the NL in walk rate (1.0 per nine) and strikeout-to-walk ratio (6.1), both for the second of three straight years. His four-year reign as the NL Cy Young winner came to an end, however, as Smoltz took home the award. While he was even better in the postseason than the year before, delivering a 1.70 ERA in five starts and throwing eight innings of shutout ball against the Yankees in Game 2 of the World Series, Maddux wound up on the short end of a 3-2 decision in Game 6, as the Bronx Bombers won their first championship since 1978.

Maddux signed a five-year, $57.5 million extension in August 1997, surpassing Barry Bonds as the game's highest-paid player in terms of average annual value. By that point he had peaked; though he would remain durable and effective while racking up high win totals, he had already slipped from being the best pitcher in the league to merely one of the best. From 1996 to 2000, he placed in the league's top three in pitching WAR four times but never led. He won his fourth ERA title in 1998 (2.22) and helped the Braves back to the World Series in 1999; in 2000, his age-34 season, he made what would be his last All-Star appearance and received the last of his Cy Young votes.

Though Maddux pitched to a 2.62 ERA (159 ERA+) in 2002, nagging injuries — including one to his lower back that forced him to start the year on the disabled list — limited him to 199 1/3 innings, his first time below 200 since 1987. That was the last season on his five-year deal; he agreed to arbitration with the Braves and signed a one-year, $14.75 million deal, to that point the largest in history. Alas, that was just in time for his real performance downturn. His ERA swelled to 3.96 in 2003, his highest since 1987; while still good for a 108 ERA+, he would never finish a season above 110 — or below a 4.00 ERA — again, largely due to a spike in his home run rate at a time when balls were still flying out of the park. After Atlanta was eliminated by the Cubs in the 2003 Division Series, Maddux returned to Chicago via a three-year, $24 million deal.

The 38-year-old Maddux joined a Cubs team that had just come within one win of a trip to the World Series and featured an impressive young rotation with Mark Prior, Kerry Wood and Carlos Zambrano. While Chicago actually won 89 games in 2004, one more than the year before, it narrowly missed the playoffs. Maddux was part of the cause, as he was pounded down the stretch, yielding 21 runs and nine homers in his last four starts and 23 innings; he finished with a 4.02 ERA and 1.5 homers per nine, the latter more than double his career rate. Still, his season wasn't without its highlights. On July 17, he blanked the Brewers for the last of his 35 career shutouts, while on Aug. 7, he beat the Giants to become the 22nd pitcher in history to win 300 games.

When Wood and Prior struggled to say healthy, Maddux couldn't do enough to halt the Cubs' slide below .500; after a 79-83 finish in 2005, they fell to 66-96 and last in the NL Central in '06. On July 26, 2005 he became the 13th pitcher to reach 3,000 strikeouts, whiffing the Giants' Omar Vizquel. Just over a year later, he escaped Chicago via a deadline trade to the Dodgers, for whom he mustered a bit of the old magic by putting up a 3.30 ERA in 12 starts as the team won the NL West. He signed back-to-back one-year, $10 million deals with the Padres, but even pitching half his games in the expansive Petco Park, he was more or less a league-average pitcher. A trade back to Los Angeles in August 2008 didn't yield the same results as before, as he was cuffed for a 5.09 ERA in seven starts. He threw three scoreless innings in relief in the postseason, an unfamiliar role; in December, he announced his retirement at age 42.

In the end, the question isn't whether Maddux belongs in Cooperstown, it's where in the pantheon he belongs. On the traditional merits, his 355 wins trail only Warren Spahn's 363 among pitchers since World War II and ranks eighth all-time. His 740 starts ranks fourth all-time, his 3,371 strikeouts 10th, his 5,008 1/3 innings 13th. Among pitchers since World War II with at least 2,000 innings, his 132 ERA+ ranks seventh behind Pedro Martinez (154), Hoyt Wilhelm (147), Clemens (143), Johan Santana (136), Randy Johnson (135) and Whitey Ford (133); Sandy Koufax (131) is eighth in less than half as many innings. At the 2,000-inning cutoff for postwar pitchers, Maddux is sixth in walks per nine (1.8), 11th in K/BB ratio (3.4) and 21st in fewest homers per nine (0.63).

Maddux is one of only four pitchers to win at least four Cy Young awards, joining Carlton, Randy Johnson (five) and Clemens (seven); Johnson won four in a row from 1999-2002 matched Maddux's feat for consecutive honors.

Additionally, Maddux won a whopping 18 Gold Gloves, more than any other player at any position. Thanks in part to the way his efficient mechanics put him in position to field the ball after he released it, he had impressive range as a fielder and was 25 runs above average via Defensive Runs Saved over the last six years of his career, the only years for which we have that data.

Aided by the addition of the third round of playoffs in 1995, he's still all over the postseason leaderboard, if not always in positive ways; his 14 losses rank second, his 11 wins only fifth. He's fourth in postseason starts (30) and fifth in innings (198), over which he put up a 3.27 ERA, not far off his regular season mark of 3.16.

From an advanced statistical perspective, Maddux's 106.8 career WAR ranks seventh all-time, with Clemens (140.3) and Tom Seaver (110.5) the only postwar pitchers above him. His 56.3 peak score is "only" 23rd all-time but still behind just Clemens (66.3), Johnson (62.0), Bob Gibson (61.6), Seaver (59.6) and Pedro Martinez (58.2) among the postwar set. Maddux loses ground to most of those pitchers in a WAR-based measurement because he didn't strike hitters out with as much frequency (6.1 per nine to Clemens' 8.6 per nine or Johnson's 10.6 per nine); thus, he has to share more of the credit with his fielders. In the end, he ranks 10th all-time in JAWS among starters, with only Clemens (103.3), Seaver (85.0) and Johnson (82.0) ahead of his 81.6 among postwar pitchers. That's not just a Hall of Famer, that's an inner-circle one.

In the 21 elections since Seaver set the record with 98.84 percent of the vote back in 1992, only six of the 29 players elected by the BBWAA have surpassed 95 percent: Steve Carlton (95.82 percent in 1994), Mike Schmidt (96.52 percent in 1995), George Brett (98.19 percent in 1999), Nolan Ryan (98.79 percent in 1999), Tony Gwynn (97.61 percent in 2007) and Cal Ripken (98.53 percent in 2007). Maddux will likely join their company, but pushing into the upper reaches to threaten Seaver's record may be out of the question. Last year saw five voters mail back blank ballots in protest of the number of PED-tainted candidates on the ballot, the latest in a trend of writers making the election about themselves instead of about the candidates. Those votes count in the total, so in an election where 569 ballots were cast, the maximum percentage any candidate could have gotten would have been 99.12 percent. Assuming those same numbers apply to this year's ballot, Maddux could only afford to have one other voter not include him among their 10 and still surpass Seaver.

Setting aside resident BBWAA curmudgeon Murray Chass' threat/promise to vote for Jack Morris and nobody else, it's not difficult to see how a voter could leave Maddux off as part of a game-theory strategy, particularly with more than 10 qualified candidates. If you're a voter who wants to make sure that the candidacy of Mike Mussina or Edgar Martinez doesn't go unnoticed, or that Morris needs your vote in his final year of eligibility, or that Roger Clemens and Barry Bonds are finally worthy of your vote after you withheld it last year, you might conclude that Maddux doesn't need your vote, and write in another name instead. Doing so might be considered a perversion of the process in the eyes of some, but with the BBWAA thus far sticking to the 10-candidate limit on the individual ballots, it's inevitable that someone will go this route.