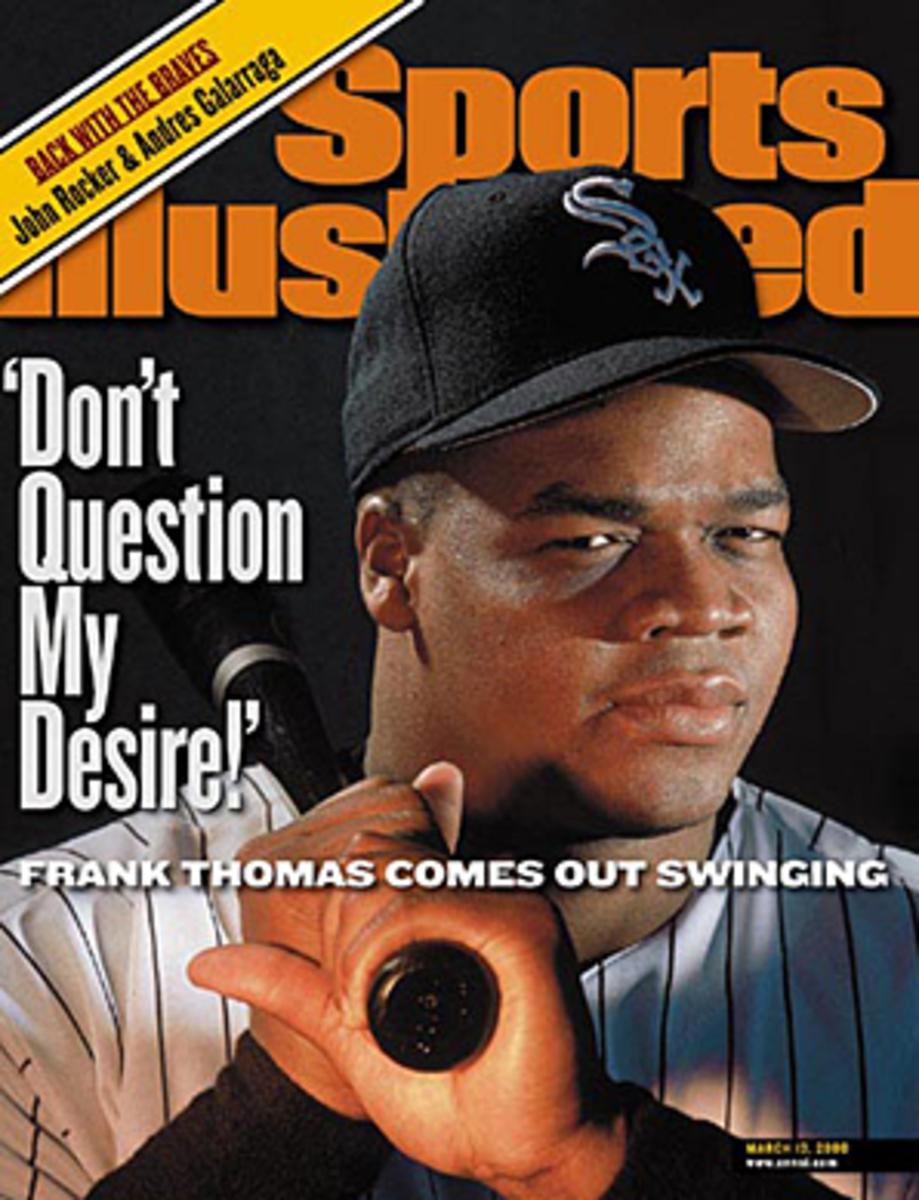

JAWS and the 2014 Hall of Fame ballot: Frank Thomas

Frank Thomas finished his career with 521 home runs. (Heinz Kluetmeier/SI)

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2014 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here. For the schedule, see here.

It's easy to be cynical about Frank Thomas, but it's also unfair. A 6-foot-5, 270-pound hulk who initially headed to Auburn University on a football scholarship, he was the brawniest of sluggers in an era typified by brawn. Between that and the connections of so many of the period's other elite sluggers to performance-enhancing drugs -- seven of the 10 who have joined the 500 home run club since the start of 1999 -- it's understandable why some might paint Thomas with the same brush.

Yet while Major League Baseball and the players' union dragged their feet when it came to cleaning up the game, Thomas was well ahead of the curve. As early as the summer of 1995, he was vocally in favor of steroid testing. In the spring of 2003, he was among a group of White Sox who decided to boycott the survey test on the grounds that doing so would increase the chances of introducing mandatory testing. In 2005, his outspoken views made him among the handful players subpoenaed to testify in front of Congress — one of only two who himself had not been connected to use. In 2007, it was revealed that he was the rare player who voluntarily cooperated with the Mitchell Report. None of that guarantees that he was clean, but no other major leaguer from the era amassed such a track record on the subject, which has to be worth something.

Few could match his track record as a hitter. Thomas never led the American League in home runs, but he bashed 521 for his career, enough to tie him with Ted Williams and Willie McCovey for 18th on the all-time list; if not for injuries, he quite possibly would have reached 600. He was so feared by opposing pitchers, and so disciplined when it came to the strike zone, that he drew 100 walks in 10 different seasons while topping 100 strikeouts just three times. He won a batting title and back-to-back MVP awards and led the AL in on-base percentage four times. Even after adjusting for the favorable offensive conditions of the era, he stands as one of the greatest hitters in baseball history. There's little doubt among voters that he belongs in the Hall of Fame, but while he's likely to receive substantial support in his ballot debut, he's hardly guaranteed an immediate entry.

Player | Career | Peak | JAWS | H | HR | SB | AVG/OBP/SLG | OPS+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Frank Thomas | 73.6 | 45.3 | 59.5 | 2468 | 521 | 32 | .301/.419/.555 | 156 |

Avg HOF 1B | 65.7 | 42.3 | 54.0 |

Born in Columbus, Ga., on May 27, 1968 — the same day as ballot-mate and fellow 1994 MVP Jeff Bagwell — Thomas excelled at three sports while growing up. Wrote Steve Rushin for a 1991 Sports Illustrated feature, "As a senior at Columbus High, Frank was a 6-foot-4 forward who could smoke the jump shot from the corner and evoke images of Auburn's Charles Barkley on the break. He hit .440 for the baseball team and 1.000 for the football team, converting all 15 of his extra-point attempts as a placekicking tight end."

Recruited by legendary football coach Pat Dye to the point that it was said to have scared off baseball scouts, Thomas accepted a scholarship to Auburn. He played tight end as a freshman in 1986, the year after Bo Jackson's departure, and caught three passes for a team that won the Citrus Bowl and finished the year ranked sixth in the country. As he had done with Jackson, Dye excused Thomas from spring football practice so he could play baseball, and he wound up setting a school record with 21 homers in his freshman year. When he suffered a knee strain in his first day of football drills during sophomore year, he abandoned the sport.

Thomas continued to excel at baseball, setting a school record with 49 career homers and winning Southeastern Conference MVP honors during his senior year. Chosen by the White Sox with the seventh pick of the 1989 draft, he hit .296/.405/.425 at Rookie and A-ball in his first professional season, and placed 29th on Baseball America's Top 100 Prospects list the following spring. After a monster spring training showing with the big club, the 22-year-old slugger hit .323/.487/.581 with 18 homers in 109 games at Double A Birmingham, a performance that would win him BA's Minor League Player of the Year honors. He made his major league debut on Aug. 2, going 0-for-4 against the Brewers but driving in the winning run on a ninth-inning fielder's choice. In 60 games for the White Sox, he hit a torrid .330/.454/.529, a portent of things to come.

Thomas put up huge numbers in 1991, his first full major league season. Batting third in a formidable lineup behind Tim Raines and Robin Ventura, he hit .318/.453/.553 with 32 homers and 109 RBIs. His on-base percentage, 138 walks and 180 OPS+ led the league, while his 7.0 WAR ranked third. He finished a solid third in that year's MVP voting behind Cal Ripken and Cecil Fielder.

Thomas backed that up with another outstanding season in 1992, leading the AL in doubles (46), extra-base hits (72), walks (122), on-base percentage (.439) and WAR (7.9). While he hit only 24 homers, legend has it that a 450-footer from that year that led White Sox broadcaster Ken Harrelson to coin the nickname "The Big Hurt," as in "Frank put a big hurt on that ball!"

He certainly applied a new level of hurt to opposing pitchers the following year, when he hit 41 homers, drove in 128 runs and slugged .607 en route to his first All-Star appearance and a unanimous AL MVP award. That performance helped the Sox win 94 games and the AL West flag in 1993, their first playoff appearance in a decade. The Blue Jays wanted no part of Thomas in the ALCS, walking him a record-setting 10 times. He still hit .353/.593/.529, but the Sox lost the series in six games.

Thomas signed a four-year, $29 million extension in October 1993, covering the 1995-98 seasons. The deal made him the game's second-highest paid player behind Barry Bonds, and while the contract was not yet in effect, he rewarded the White Sox with numbers that went to video-game-level insanity in the strike-shortened 1994 season. He hit .353/.487/.729 with 38 homers, led the league in on-base and slugging percentages as well as runs (106), extra-base hits (73), walks (109), OPS+ (212) and WAR (7.1) en route to another MVP award. While Thomas couldn't maintain that torrid pace, he went on to hit a combined .317/.433/.570 for a 158 OPS+ over the next six seasons (1995-2000), averaging 34 homers and 5.0 WAR per year. The White Sox finished below .500 in four of those years, but they did win the AL Central in 2000.

In 1997, Thomas hit .347/.456/.611, winning his lone batting title while leading the circuit in OBP for the fourth time and in OPS+ (181) for the third. After that season, he signed an extension that could be worth a maximum of $85 million over six years, keeping him with the White Sox through 2006 if options covering the last two years were exercised.

Under new manager Jerry Manuel, Thomas began DHing more often than he played first base in 1998, no great loss given that he had been roughly seven runs below average per year in the field through his first eight seasons according to Total Zone. Even so, he wrestled with the decision, later saying, "I know I need to play first base to get in" a reference to his Hall of Fame chances. Distracted by marital and financial problems — the latter stemming largely from his record company, Un-D-Nyable Entertanment — he began pressing at the plate, and his production slid to .265/.381/.480 that year, career worsts across the board.

Thomas rebounded only partially in 1999 (.305/.414/.471 with 15 homers), losing nearly all of September to a bone spur the size of a golf ball in his right ankle, as well as a corn on his disfigured little toe, both of which required season-ending surgery. In September of that year he refused a pinch-hitting assignment in the nightcap of a doubleheader, creating a firestorm of controversy and lingering bad blood, both within the organization — particularly with Manuel and general manager Kenny Williams — and from media and fans.

Healthy in 2000, Thomas managed to roll back the clock to recover his vintage form, hitting .328/.436/.625, setting career highs in homers (43) and RBIs (143) and finishing second in the AL MVP voting behind Jason Giambi. He had no chance to maintain that form, as a torn right triceps cost him all but 20 games in 2001. While he hit a reasonably productive .252/.361/.472 with 28 homers and 92 RBIs in '02, his contract allowed owner Jerry Reinsdorf to invoke an unprecedented "diminished skills" clause that deferred all but $250,000 of his $10.3 million salary; Reinsdorf went back on his word to do so.

Under terms of the clause, Thomas was allowed to opt out via free agency rather than have his salary deferred; he did, though he wound up returning to Chicago via a one-year, $5 million deal that included incentives and three mutual options, guaranteeing him $22.5 million. He had a big 42-homer season in 2003, but was limited to 74 games in 2004 and 34 in 2005 due to stress fractures in his left foot and a bone graft in his left ankle. He was a bystander when the White Sox swept the Astros in the 2005 World Series for their first championship since 1917 — a "seriously happy" one, to use his words, but a bystander nonetheless.

Chicago bought out its end of Thomas' mutual option after the season, trading for Jim Thome and thus ending the Big Hurt's 16-year run on the South Side on an acrimonious note. Thomas later said that had he known the Sox weren't going to bring him back, he would not have agreed to throw out a ceremonial first pitch in the playoff or to address the crowd at the end of the team's victory parade. He complained about not even receiving a phone call from Reinsdorf over the option decision, and received a harsh parting shot from Williams: "He's an idiot. He's selfish. That's why we don't miss him."

The 38-year-old Thomas took his wounded pride and signed with the A's for just $500,000 plus incentives, then responded with a 39-homer .270/.381/.545 season that helped Oakland win the AL West and led to a fourth-place finish in the AL MVP voting. He parlayed that strong showing int a two-year, $18.1 million deal with the Blue Jays but after hitting 26 homers in his first season — including number 500 off the Twins' Carlos Silva on June 28, 2007 — he started slowly in his second one, going 10-for-60 with three homers in 16 games. Shockingly, Toronto cut bait on April 20, leaving them on the hook for the bulk of Thomas' $8 million salary but avoiding an attainable $10 million vesting option for 2008. Thomas returned to Oakland, but quadriceps problems limited him to just 55 more games and a meager .263/.364/.387 line. While he sought a job for the 2009 season, he was unable to find one, leading him to officially retire in February 2010.

Thomas finished his career with numbers that put him among the elite hitters in baseball history. He's one of seven hitters who have maintained a "golden ratio" of at least a .300 batting average, .400 on-base percentage and .500 slugging percentage over the course of 10,000 plate appearances or more:

Player | Years | PA | AVG | OBP | SLG | OPS+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Babe Ruth | 1914-1935 | 10622 | .342 | .474 | .690 | 206 |

Ty Cobb | 1905-1928 | 13082 | .366 | .433 | .512 | 168 |

Stan Musial | 1941-1963 | 12717 | .331 | .417 | .559 | 159 |

Tris Speaker | 1907-1928 | 11992 | .345 | .428 | .500 | 157 |

Frank Thomas | 1990-2008 | 10075 | .301 | .419 | .555 | 156 |

Mel Ott | 1926-1947 | 11348 | .304 | .414 | .533 | 155 |

Chipper Jones | 1993-2012 | 10614 | .303 | .401 | .529 | 141 |

Thomas and Jones are the only two of those seven to complete the feat entirely in the post-1960 expansion era. Among players with at least 8,000 plate appearances, Thomas' .419 on-base percentage ranks 11th, his .555 slugging percentage is 14th and his 156 OPS+ is 12th. In addition to being tied for 18th in home runs, he's 10th in walks (1,667), 22nd in RBIs (1,704) and 29th in extra-base hits (1,028). While he only made five All-Star teams, he won two MVP awards and placed in the top three in voting five times.

As for the home runs, it's not too hard to imagine him reaching 600. From 2001 through 2008, he averaged 22 homers and 99 games a year. Prorate that out to 140 games per season, and it's an extra nine homers each year and 72 for his career, putting him within shouting distance of 600 and likely giving him enough buzz to land a job for 2009.

Thomas doesn't need the homers to boost his Cooperstown case on the advanced merits, as it's already strong. Even given the fact that he was a below-average defender (-64 runs via Total Zone) who spent 57 percent of his career as a DH — and thus incurred the positional penalties built into WAR for doing so, costing him roughly an extra half-win per full season at the position — he ranks eighth among first basemen in career WAR (73.6), about eight wins above the Hall of Fame standard at the position. His 45.3 peak WAR ranks 11th, three wins above the standard, and his 59.5 JAWS ranks ninth, clearing the bar by 5.5 points and beating out 12 of the 18 enshrined first basemen (all but Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Cap Anson, Roger Connor, Dan Brouthers and Johnny Mize). Among post-World War II first basemen, only Albert Pujols (77.3 JAWS) and Bagwell (63.8) outrank him. That's a clear Hall of Famer.

In an era when so many voters are skeptical of the veracity of such eye-popping achievements, particularly on the offensive side, it's worth reviewing Thomas' credibility on the topic of performance-enhancing drugs. He was among the early proponents of testing, telling The Sporting News' Bob Nightengale in July 1995, "I'd love to see testing myself… If it can be done in every other sport, why not? At least it would get rid of the suspicions."

Eight years later, when the players' union agreed to submit to a supposedly anonymous survey test that would measure PED use among players and trigger the introduction of mandatory random testing if at least five percent tested positive, Thomas was among a group of White Sox who planned to boycott the test, either because they felt the forthcoming policy wouldn't be strong enough or because doing so would count such boycotters as positive tests, thus increasing the likelihood of mandatory testing being introduced. While the players ultimately relented, author Howard Bryant, in his book Juicing the Game, lauded Thomas' actions as "a form of civil disobedience to force stronger testing the following year."

In March 2005, Thomas was one of six players who agreed to testify in front of Congress on the game's PED problem. Still recovering from foot surgery, he was allowed to appear via a video hookup, though he was largely forgotten after making his opening statement, overshadowed by the juicier theatrics of Jose Canseco, Mark McGwire, Rafael Palmeiro, Curt Schilling and Sammy Sosa. More noteworthy was the fact that he was the only active player who was not connected in any way to PEDs yet voluntarily spoke to Senator George Mitchell for his report on PED use within the game. Giambi was compelled to cooperate due to his involvement in the BALCO scandal, and one unidentified player also spoke to investigators but was exonerated by evidence and thus not named in the report.

"The whole reason I did it was because I couldn’t believe other guys weren’t talking to him. I had nothing to hide," Thomas said later of his interview with Mitchell, though he also added, "I told him that I hadn’t seen or heard anything like that in 15 years… I have never had a teammate say something like, ‘this guy is juicing.’ It’s never even come up. I guess I must be the only one.”

That statement may sound naive, but the multitude of stories of Thomas' aloof nature in the clubhouse suggest he didn't exactly have his finger on the pulse of whatever might have been going down. In a January 2013 radio interview, he conceded his naivete: "It was a secret society. I had no idea. I think I was the one guy that when they were having that conversation they would stop quickly when I walked in the room. For many, many years I had a lot of teammates involved and I had no idea it was going on the way it was going on."

Thomas' actions with regards to PEDs don't make him into any kind of hero, but they should at least be enough to place him above the garden-variety suspicion that has acted as a drag on the candidacies of players who never tested positive, such as Bagwell, Craig Biggio and Mike Piazza. The combination of that and his overwhelming statistical accomplishments set him apart from the ballot's other members of the 500 home run club such as Bonds, McGwire, Palmeiro and Sosa.

should

Maddux is a lock