JAWS and the 2014 Hall of Fame ballot: Tom Glavine

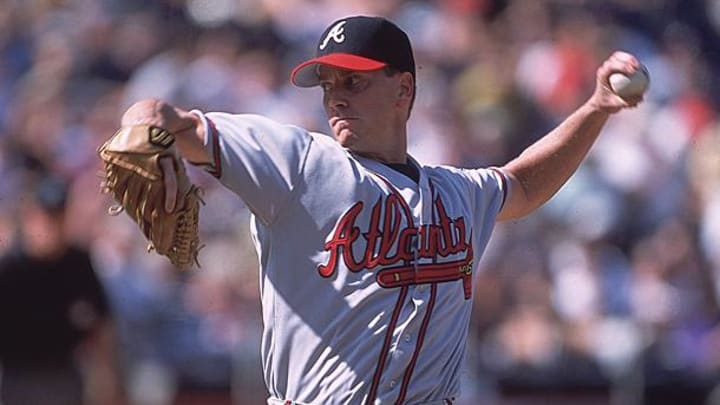

Tom Glavine spent 17 of his 22 major league seasons with the Braves. (John W. McDonough/SI)

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2014 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here. For the schedule, see here.

Tom Glavine was the epitome of the crafty lefty. Much like his longtime teammate and fellow 2014 ballot newcomer Greg Maddux, he lacked the stuff to just rear back and blow hitters away, instead relying primarily on a mid-to-high-80s fastball and a very good changeup. He made his living on the outside edge of the plate, demonstrating an uncanny ability to expand the strike zone, thus avoiding contact and putting hitters in unfavorable counts.

You had to see it to appreciate it fully, because his raw rate stats — particularly his 5.3 strikeouts and 3.1 walks per nine, not to mention his 3.54 ERA — are certainly unassuming. Which isn't to suggest that his case is the second coming of Jack Morris, one that lacks a foundation of outstanding run prevention, because he did quite well on that score in the context of the times, and it's reflected in both his traditional and advanced metrics.

Glavine was a master of sequencing and of minimizing the damage caused by the walks and homers he allowed. Like Maddux, he was exceptionally durable, topping 200 innings 14 times in his 22-year career and 180 innings 19 times in the 20 full seasons of that span; meanwhile, he avoided the disabled list until his age-42 season. He racked up wins, reaching 20 five times -- more often since the advent of the designated hitter than any pitcher except Roger Clemens -- and eventually joining Maddux in the 300-win club. More than any other player, he put the Braves back on the map, winning two Cy Young awards and helping his teams reach the playoffs 12 times, including 11 in a row for Atlanta from 1991-2002, the 1994 strike season excepted. He was part of five pennant winners, and nailed down the Braves' lone world championship in that span with one of the best pitching performances in World Series history.

Glavine doesn't quite measure up to Maddux in terms of his overall body of work, but he's nonetheless worthy of election to the Hall of Fame. This crowded ballot offers no guarantees, but he has a reasonable chance to go in side-by-side with his fellow ace this year, joined by longtime manager Bobby Cox.

Pitcher | Career | Peak | JAWS | W | L | ERA | ERA+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tom Glavine | 81.4 | 44.3 | 62.9 | 305 | 203 | 3.54 | 118 |

Avg HOF SP | 72.6 | 50.2 | 61.4 |

Born in Concord, Mass., and raised in the nearby town of Billerica, Glavine excelled in baseball growing up, though he was even more keen on hockey. In high school, he drew attention from scouts in both sports. He aspired to play hockey at Harvard, but despite good grades, his struggle with the SATs cost him that opportunity. He signed a letter of intent to the University of Massachusetts-Lowell on a hockey scholarship with plans to play both sports, but the NHL's Los Angeles Kings drafted him in the fourth round in 1984, and the Braves chose him in the second round that year as well, 16 picks behind future teammate Maddux. The Kings made no attempt to sign him, but the Braves did, first offering a $60,000 bonus and then bumping it to $80,000 — first-round money, in those days — to convince him to sign.

Glavine dominated in the low minors, striking out more than a batter per inning in his first two professional seasons, but his strikeout and walk rate began to converge by the time he reached the high minors. He made an inauspicious major league debut as a 21-year-old on Aug.17, 1987, getting pounded for 10 hits, five walks and six runs in 3 2/3 innings by the Astros, who started Mike Scott. Glavine was knocked around for a 5.54 ERA in nine starts for that 92-loss Braves team, though he did have his moments; in his final start of the year, also against Houston, he went seven innings and allowed just one unearned run despite walking seven. The beatings continued during Atlanta's 106-loss 1988 season; Glavine was hit for a 4.56 ERA (80 ERA+) in 195 1/3 innings and led the NL with 17 losses. He turned the corner with a 14-8 season and a 3.68 ERA (98 ERA+) the following year, aided by his accidental discovery of a circle changeup. As Leigh Montville explained in a July 13, 1992 feature for Sports Illustrated:

In spring training of 1989, Glavine was standing in the outfield during batting practice. A ball rolled toward him. He bent, picked it up...and somehow his fingers landed differently on the ball. The middle and ring fingers were along the seams. The circle on the side was exaggerated, the tip of the index finger on top of the thumbnail. Glavine threw the ball into the infield. Voila! A career was born.

"Throwing that way just seemed natural to me," he says. "I don't know why, but from that first throw the pitch was natural. I started throwing it that day."

Glavine broke out in 1991, his first full season under Cox, who had spent four and a half years as the team's general manager before firing manager Russ Nixon in June 1990. On the strength of a 12-4, 1.98 ERA first half, the 25-year-old southpaw started the All-Star Game, and finished the year with a 20-11 record, a 2.55 ERA and 7.0 strikeouts per nine. He led the league in wins and complete games (nine) as well as ERA+ (153) and WAR (8.5); those last three marks wound up as his career bests. Not only did he win his first Cy Young, he headed a rotation that included 24-year-old John Smoltz and 21-year-old Steve Avery, all of whom helped Atlanta vault from last place in the NL West with 65 wins to first with 94 wins. His team lost both of his starts in the NLCS against the Pirates and his first one in the World Series against the Twins — all while supporting him with a grand total of three runs — but he ground his way through a mediocre Game 5 start to earn a win. That would be the Braves' last victory in a thrilling seven-game classic that they lost.

Glavine reeled off a similarly strong campaign in 1992, starting the All-Star Game and going 20-8 with a 2.76 ERA and five shutouts in 239 1/3 innings; that said, his strikeout rate dipped to 5.2 per nine and his WAR to 3.8. The Braves advanced past the Pirates in the NLCS despite his again losing both series starts, including an eight-run, one-inning-plus pounding in Game 6 that forced Game 7, where pinch-hitter Francisco Cabrera broke the Pirates' hearts. Glavine was strong in the World Series against the Blue Jays, going the distance in a 3-1 win in the opener but winding up on the short end of a 2-1 battle with Jimmy Key in Game 4; Toronto prevailed in six. After the season, Glavine finished second in the Cy Young voting to Maddux, who soon joined him in Atlanta via a five-year, $28 million deal. Glavine cashed in as well that winter, with a four-year, $20.5 million extension covering the 1993-96 seasons.

Though he again led the league with 22 wins in 1993, Glavine took a backseat to Maddux, who was just starting an unprecedented run of four straight Cy Young awards. The so-called "Five Aces" rotation (rounded out by Smoltz, Avery and a less-than-worthy Pete Smith) helped the Braves to 104 wins and another NL West flag, though the team lost a six-game NLCS to the Phillies. Despite a career-best 7.6 strikeouts per nine in the strike-shortened 1994 season, Glavine wasn't as impressive; his ERA shot up to 3.97 in part due to a 41-point jump in batting average on balls in play from the year before, from .284 to .325. By this point, Glavine was at peak visibility, as the National League player representative during the negotiations leading up to and during the strike, and thus one of the faces of the union, for better or worse.

Glavine heard his share of boos from an angry Atlanta crowd once he returned to work in 1995, but he nonetheless found top form, with a 3.08 ERA in 198 2/3 innings, good for 4.8 WAR, third in the league. More importantly, he helped the Braves win their first world championship since 1957. Glavine posted a 1.61 ERA across four starts that October in helping the Braves past the Rockies, Reds and Indians. He capped that run with eight innings of one-hit, eight-strikeout ball in a 1-0 Game 6 squeaker that clinched the championship. The lone hit he allowed was Tony Pena's single to lead off the top of the sixth inning, while the lone run came when Atlanta's David Justice pounded a solo homer to lead off the bottom of the frame.

"Glavine did not paint the lower outside corner so much as he coated it with lacquer, pitch after pitch after pitch," wrote Tom Verducci in his series wrapup for SI. "It may have been the best-pitched game among the 91 that have ended a World Series. It definitely was the only one-hitter among them." Note that Morris' 10-inning shutout in Game 7 of 1991 still had to be fresh in Verducci's mind when he wrote that statement; its legend had not yet grown out of proportion. Though Glavine didn't go the distance — to say nothing of extra innings — his 85 Game Score ranks third among all World Series clinchers, one point ahead of Morris.

For his performance, Glavine was named World Series MVP, and he wound up finishing third in the Cy Young voting behind Maddux, who won unanimously for the second year in a row. That year's performance kicked off a particularly strong four-year run over which Glavine posted a 2.87 ERA (148 ERA+) while averaging 226 innings, 6.1 strikeouts per nine and 5.6 WAR. His 22.2 WAR for the span ranked fifth in the majors behind Maddux (31.2), Roger Clemens (29.6), Kevin Brown (27.9), Pedro Martinez (24.8) and Randy Johnson (23.6). He helped the Braves back to the World Series with another brilliant October (1.69 ERA in four starts) in 1996, but despite seven strong innings opposite David Cone, he was on the short end of a Game 3 loss to the Yankees, and his turn for Game 7 never came.

Glavine signed a four-year, $34 million extension in May 1997, one that included an $8 million option for 2002. He won 20 games for the fourth time in 1998, finished fourth in the league with a 2.47 ERA and took home his second Cy Young. His ERA ballooned to 4.12 in 1999 as his BABIP again jumped 41 points from year to year (.277 to .318), but he helped the Braves to another pennant, their fifth in nine seasons. Amid a sweep by the Yankees, he was roughed up in his lone World Series start.

Glavine spent three more strong years in Atlanta, including a 21-win 2000 season that led to a second-place finish in the Cy Young voting, just ahead of Maddux (who had two fewer wins but 1.7 more WAR and the lower ERA). By this point, he had expanded his arsenal and adapted his style. Wrote Verducci in a June 17, 2002 feature, " No longer just a fastball-changeup savant who lives on the outside part of the plate (give or take a few inches granted by generous umpires), Glavine has broadened his repertoire to include backdoor sliders, cut fastballs and—gasp!—regular visitations to the inside corner." Elsewhere in the piece, Glavine downplayed another one of his offerings: "It's a good curveball for 58 feet, but it's lousy for 60 feet."

After a typically strong 2002 season (18-11, 2.96 ERA in 224 2/3 innings) that included his eighth All-Star appearance, the 36-year-old Glavine did the nearly unthinkable, leaving the Braves to sign a three-year, $35 million deal with the rival Mets, whom he chose over the Phillies. Thus ended not only Glavine's 17-year run with Atlanta but also his decade as part of an ace-level trio with Maddux and Smoltz. Though the Braves won only one championship during that 1993-2002 run, they made the playoffs in every year but 1994, and their .613 winning percentage was the majors' best, well ahead of the number two team (the Yankees at .595) and miles beyond the number two NL team (the Astros at .541).

Glavine's initial year in New York was a dreadful one; the Mets went 66-95 and he was cuffed for a 4.52 ERA. His 93 ERA+ marked the first time he had been worse than league average since 1990, and his 183 1/3 innings ended a string of seven straight seasons with at least 200. On a positive note, in late September, he was joined by his brother Mike, seven years his junior and at that point an organizational player who had been beating the bushes for nine seasons. Little brother's lone big league start at first base came in big brother's Sept. 25 start against the Pirates.

Glavine recovered his form well enough to post a 3.65 ERA across an average of 207 innings over the next three seasons and making the All-Star team twice. In 2006 -- after his $10.5 million vesting option for the year had been triggered -- he helped a considerably improved Mets club win 97 games and their first NL East title since 1988; in doing so they ended Atlanta's long run atop the division. Glavine was brilliant in his first two postseason starts, throwing a combined 13 shutout innings against the Dodgers in the Division Series and then against the Cardinals in the Championship Series opener. He lasted just four innings in a Game 5 loss, however, and the Mets ultimately lost in seven.

If that was disappointing, the next year was even moreso, though Glavine did notch his 300th win on Aug. 5, 2007 — the 23rd pitcher to do so — receiving a generous ovation from the Wrigley Field crowd after beating the Cubs. The Mets led the NL East by seven games with 17 left to play, but they went 5-11 over their next 16 games as the Phillies caught up. With the division title on the line, Glavine — who had been roughed up for 10 runs and 20 hits in 10 innings over his previous two turns — got the call to start Game 162 against the Marlins. He retired just one of nine batters faced, hit pitcher Dontrelle Willis with a changeup and was charged with seven runs allowed in an 8-1 loss. Showered with boos as he left the Shea Stadium mound, he continued to take abuse from Mets fans over his refusal to call himself "devastated" over the loss.

So much for New York. In November 2007, Glavine signed a one-year, $8 million deal to return to the Braves, but a hamstring strain and a torn flexor tendon limited him to a 5.54 ERA over 13 starts, only one of which came after June 10. He underwent elbow and shoulder surgery in August, and signed an incentive-based deal to return for one more year at age 43, but the Braves released him in early June after four rehab starts in order to clear a roster spot for Tommy Hanson. Glavine mulled pressing onward, but he didn't pitch again. He announced his retirement on Feb. 11, 2010, the same day that 2014 ballotmate Frank Thomas did.

Glavine ended his career with some impressive totals. He made 10 All-Star teams, led his leagues in starts six times and in wins five times. His 305 wins ranks 21st all-time, his 4,413 1/3 innings rank 30th, while his 1,500 walks and 682 starts both rank 12th; he never made a relief appearance and so holds the record for most starts without doing so, well ahead of CC Sabathia (415) , who's second with that distinction. Though the data only goes back to 1946, his 420 double plays generated ranks sixth — two twin killings behind Maddux —which is notable given his relatively unassuming peripheral stats.

Even as a whole branch of sabermetrics sprung up around the discovery of how little influence pitchers have on preventing hits on balls in play, Glavine showed himself to be something of an outlier, with a .285 BABIP, 10 points below the major league average during the span of his career. Among the 16 pitchers with 3,000 innings since 1983 — a span chosen so as to cut out a whole cohort of pitchers who benefited from the low-offense era in the 1970s and 1980s — he ranks third behind Tim Wakefield (.276) and Orel Hershiser (.280). Via FanGraphs' Fielding Independent Pitching stat, Glavine's body of work projects to a 3.95 ERA. He beat that by 0.41 runs, the fifth-widest margin among the 92 pitchers with at least 2,000 innings since '83.

Like Maddux and Smoltz, Glavine is all over the postseason leaderboard thanks to the Braves' perennial runs into October. His 35 starts and 218 1/3 innings both rank second, while his 14 wins are third, his 16 losses first, his 143 strikeouts fifth. Despite ending up on the short end more often than not, Glavine's 3.30 ERA in the postseason was 0.24 lower than his regular season mark. Meanwhile, his eight World Series starts and 58 1/3 innings both rank third among pitchers since the division play era began in 1969.

From an advanced perspective, Glavine's 81.4 career WAR ranks 25th all-time, sandwiched between Nolan Ryan and Curt Schilling and ahead of 38 out of the 57 Hall of Fame starters; it's 8.8 wins above the average for that group. Suppressed by his low strikeout rate and thus a larger share of the credit going to his fielders than it would for a power pitcher, his 44.3 peak WAR isn't as impressive, ranking 66th all-time and 5.9 wins below the average Hall starter. Even so, his 62.9 JAWS is 1.5 points ahead of the Hall average, good enough for 30th all-time, and 15th among post-World War II pitchers. While it may not be as definitive a case as that of Maddux, it's a Hall of Fame one nonetheless.

Glavine's credentials assure him of a spot in Cooperstown, but as I noted upon his retirement, those in the 300-win club often have to wait around to get in. Limiting the scope to those who reached 300 after World War II, Warren Spahn entered on his first try in 1973 (his eligibility was delayed by minor league service in 1966 and 1967, which would no longer be the case), as did Tom Seaver (1992), Steve Carlton (1994) and Nolan Ryan (1999). On the other hand, Gaylord Perry needed until his third try in 1991, Early Wynn until his fourth in 1972, Phil Niekro and Don Sutton their fifth in 1997 and 1998, respectively. Clemens didn't come close last year, his first time on the ballot, and he doesn't figure to this time around, either, though that owes to his connection to performance-enhancing drugs.