JAWS and the 2014 Hall of Fame ballot: Why there's a backlog -- and how to fix it

Had one possible solution to the glut of candidates been in place just a few years ago, Jack Morris would have already been elected. (Bill Chan/AP)

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2014 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here. For the schedule, see here.

Having spent the past few weeks reviewing the careers of all 36 players on the BBWAA 2014 Hall of Fame ballot, what's abundantly clear is that this year's crop has far more qualified candidates than an individual voter can fit on his or her 10-slot ballot. Before delving into the difficult choices and possible coping strategies available to an individual voter — something I intend to mirror with my own final (virtual) ballot — it's worth a closer look at how this backlog occurred.

Historically, the BBWAA has elected candidates at a gruelingly slow pace. Going back to the inaugural class of 1936, and including the special elections for Lou Gehrig and Roberto Clemente upon their tragically premature deaths, it has tabbed a total of 111 players. That's 111 over 78 years, though that doesn't mean elections were held every year. From 1940-45 the voting was done on a triennial basis, while from 1957-65, it was done on a biennial basis; it's been annual since 1966. In any event, that's an average of 1.42 players elected per year (not per election), a number that hasn't moved much even as the size of the major leagues has nearly doubled from 16 to 30 teams. Over the past 25 election cycles (1989-2013), the average is up to a whopping 1.52, though over the last 10, it's 1.40.

Within those past 25 cycles, the organization has elected three candidates in a given year just twice: in 1991 (Rod Carew, Gaylord Perry and Ferguson Jenkins) and 1999 (Nolan Ryan, George Brett and Robin Yount). Meanwhile, it has pitched two shutouts along the way, in 1996 and 2013. Not since 2004 and '05 has the BBWAA elected multiple players in back-to-back years, though they have tabbed two players three times since then — a bounty compared to the 1993-98 period, when five candidates were elected over a six-year span, no more than one in a year. Even so, with last year's shutout, the past six election cycles have sent just seven players to Cooperstown, only one of whom has made it on the first try (numbers in parentheses indicate years on the ballot):

2008: Goose Gossage (9)

2009: Rickey Henderson (1), Jim Rice (15)

2010: Andre Dawson (9)

2011: Bert Blyleven (14), Roberto Alomar (2)

2012: Barry Larkin (3)

2013: Nobody

All in all, that pace can best be described as glacial; at worst, it's cruel. Once upon a time, the writers could kick the can(didacies) down the road and expect the Veterans Committee to produce a secondary stream of honorees, albeit via an admittedly flawed process rife with cronyism and vote-trading. Like its predecessor the Old-Timers Committee, the VC was originally supposed to help manage more than half a century of backlog, given that major league baseball started in 1871, 65 years before the first Hall class. But whereas a process with 400- or 500-plus writers can produce a consensus that is protected from the outsized influence of a few individuals, the same can't be said for the VC, as I noted in exploring its history earlier this year. From 1967-76 in particular, committees featuring Hall of Famers Frankie Frisch, Bill Terry and/or Waite Hoyt voted in numerous former teammates, many of whom rank among the worst at their positions via JAWS.

Amid several tweaks to the VC system over the past decade and a half, just three players — not counting managers, executives, umpires or Negro Leaguers — have been elected via such processes over the past 13 years. Two of them came since the 2010 split into three separate (and unequal) committees based on chronological periods, and one of those players, Deacon White, hadn't played in 123 years. Admittedly, there hasn't been a whole lot to choose from when it comes to strong candidates, because the writers do a reasonable job of picking those over.

Still, it's not hard to think of instances where both processes have failed miserably, such as that of Ron Santo, Bobby Grich, Ted Simmons and Lou Whitaker. All four have very good cases based upon both traditional and advanced metrics, but all fell off the BBWAA ballot after receiving less than five percent of the vote in their first go-round. Santo was among a handful of players restored via a 1985 amnesty, but he never received more than 43.1 percent of the vote during his 15 years on the ballot, and he went 0-for-4 in front of the VC until it finally elected him in December 2011, one year after his death. Simmons has failed to get the time of day in his two VC appearances, including via this year's Expansion Era committee, while Grich and Whitaker have yet to appear on that ballot.

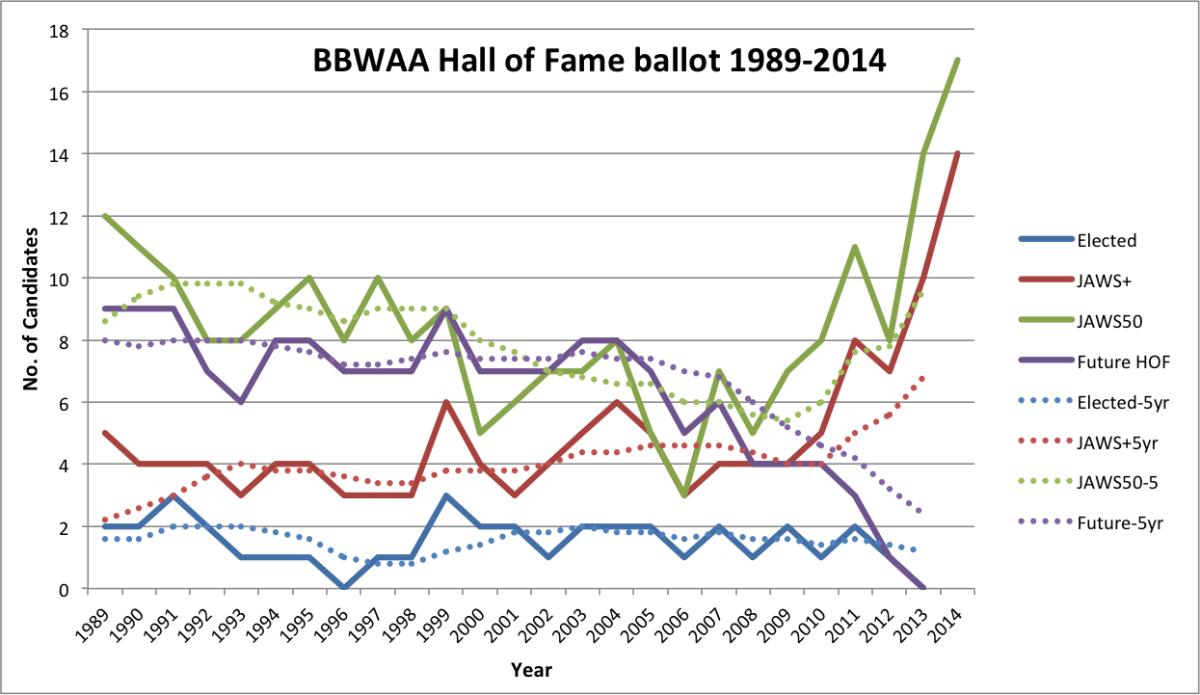

The upshot is that the failure of the secondary process leaves plenty of reason to be concerned about the mounting number of qualified candidates on the BBWAA ballot, something that becomes more striking in a visual representation:

That's the past 25 years of voting plus this year, with raw data (solid lines) and rolling five-year averages (dotted lines). Elected is the number of candidates who reached the necessary 75 percent that year; Future HOF is the total number of candidates on the ballot who made it eventually (including that year), either via the BBWAA or the various VC processes. JAWS+ is the number of players on the ballot who exceed the standard at their position using my system, and it's a strict count, without considering position changes or non-WAR-based data such as awards, postseasons and historical accomplishments that can help shade a candidate's case (in other words, 3,000-hit man Craig Biggio isn't counted in that total). JAWS50 is the number of candidates on the ballot whose scores exceed 50 points — a number that puts a candidate within hailing distance of the standard at their position, close enough where the awards, postseason and other factors might reasonably be enough to put a player over the top. For that latter figure, I've counted catchers who exceed 40 points, since the average at that position is lower.

In any case, you can see that based either upon JAWS+ or JAWS50, the number of qualified candidates on the ballot is skyrocketing beyond anything seen in the previous 25 years. In fact, the same holds true if one looks back to 1966 — there's never been a flood like this. Meanwhile, the number of candidates elected by the BBWAA has remained more or less constant, but the average number of future Hall of Famers on the ballot has plummeted, both due to the fact that the books aren't closed on some of those holdovers, and because the secondary pathway has been more or less closed down.

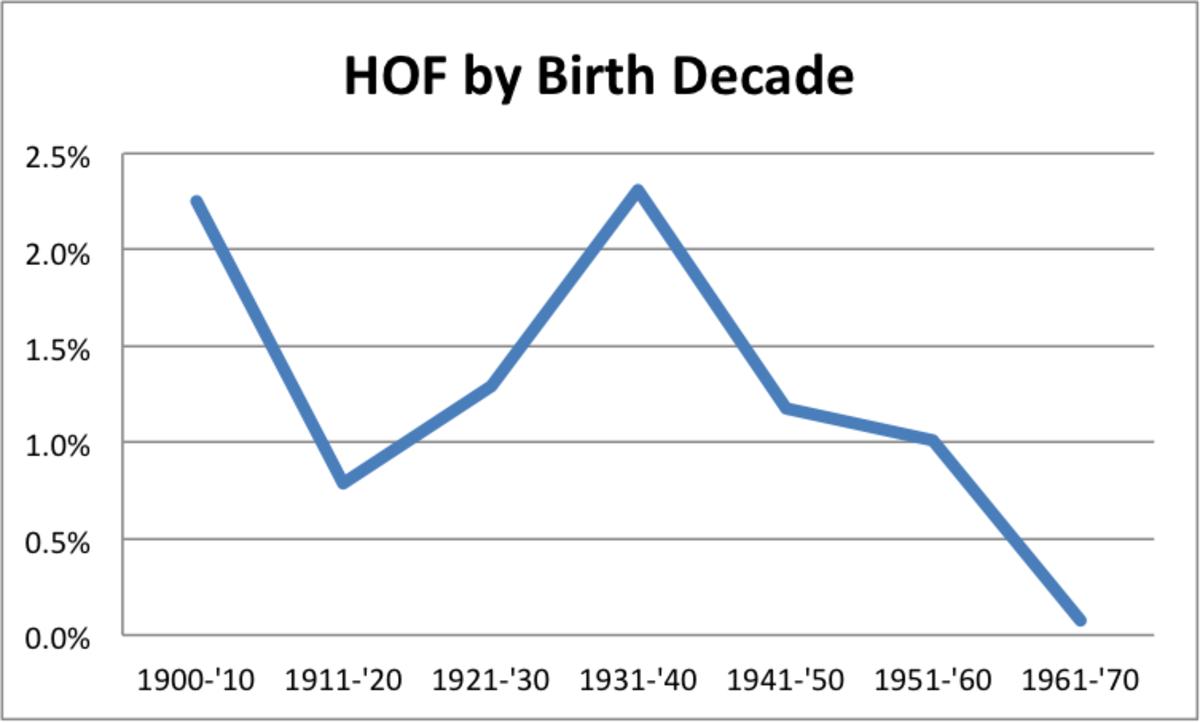

Viewing the situation a different way, earlier this month FanGraphs' David Cameron published a study illustrating the dwindling level of representation in the Hall by birth decade. Here's a quick and dirty graph:

Here's an amalgamation of Cameron's underlying table and its follow-up. It expresses the total number of players born in those years, the percentage of those who made the Hall of Fame and then looks at the number who reached either 5,000 plate appearances or 2,000 innings (roughly 10 full seasons of work) and the percentage of that group to wind up in Cooperstown. This table eliminates, among others, the increasing number of middle relievers with no Cooperstown future whatsoever. (Note that the total number of players double-counts a relatively small number from early in the game's history who reached both of those plateaus during their careers).

Year of Birth | Players | Pct in HOF | Qual Player | Pct in HOF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

<1900 | 6,431 | 2.0% | 258 | 24.8% |

1900-'10 | 1,289 | 2.2% | 93 | 25.8% |

1911-'20 | 1,769 | 0.8% | 66 | 25.8% |

1921-'30 | 1,475 | 1.3% | 77 | 16.9% |

1931-'40 | 1,428 | 2.3% | 99 | 26.3% |

1941-'50 | 1,953 | 1.2% | 168 | 8.3% |

1951-'60 | 2,275 | 1.0% | 147 | 11.6% |

1961-'70 | 2,656 | 0.1% | 160 | 1.3% |

Total | 19,276 | 1.8% | 1068 | 16.6% |

No matter how you look at it, the 1961-70 birth period is drastically underrepresented, with just two players — Barry Larkin (1964) and Roberto Alomar (1968) — inducted so far. Depending upon which way you look at it, that's roughly one-tenth the representation of each of the previous two decades, which themselves are only represented at about half the frequency of previous periods. Currently, the youngest pitcher in the Hall of Fame is Dennis Eckersley, who was born in 1954; he was elected back in 2004. Greg Maddux (b. 1966) will change that, and also overtake Blyleven (b. 1951, elected in 2011) as the youngest enshrined starting pitcher; Tom Glavine, who's three weeks older than Maddux, could join the ranks this year as well.

Performance-enhancing drugs and the electorate's split about how to handle candidates who may have used them account for part of the backlog, particularly with regard to the position players on the ballot. Barry Bonds exceeds the JAWS standard (JAWS+, from above) by a country mile, but Rafael Palmeiro just edges over the line, and both Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa reach the 50-point threshold (JAWS50, from above) without exceeding the standard. That still leaves seven hitters who clear the strict standard, plus Biggio, who has over 3,000 hits and thus virtually no precedent for being left out. Among the pitchers, PED-tainted Roger Clemens is in the same class as Bonds, but even without him, four others (Maddux, Glavine, Curt Schilling and Mike Mussina) clear the strict standard. Even a voter going the law-and-order route is faced with 12 very worthy candidates, and that's without considering that roughly two-thirds of the electorate believes that Jack Morris belongs, and that roughly half feels the same way about Lee Smith.

The glut of qualified candidates suggests that the voting process needs reform, whether by expanding the number of available slots on a ballot beyond 10, lowering the threshold for election below 75 percent or at least getting rid of the five-percent minimum rule so that candidates can't get squeezed off the ballot amid a rising backlog. Of those three, the five-percent rule has the flimsiest history; it wasn't introduced until 1979, it was tweaked again in 1980 and the aforementioned 1985 amnesty restored eligibility to several candidates. The 10-man rule, which has been around since the institution's inception, probably has the highest likelihood of being changed, but looking over the voting history, I wonder if that's the right route to go.

Instead, I think it's worth considering lowering the voting threshold, which has also remained unchanged since 1936. As I've noted several times in the 11 years that I've been doing my annual JAWS-based ballot reviews, only one candidate, Gil Hodges, has passed the 50 percent threshold and then failed to gain election eventually either via the BBWAA or the Veterans Committee. The current ballot contains six players who have reached 50 percent at least once in Biggio, Morris, Jeff Bagwell, Mike Piazza, Tim Raines and Smith, so Hodges may eventually have company, but the worst-case scenario points to Morris (who's in his final year of eligibility) and Smith (in his 12th year) eventually having their cases be decided by whatever form the VC takes in future years. The other four players from that group are less than halfway through their 15-year windows of eligibility; Raines is in his seventh year, Bagwell his fourth, Biggio and Piazza their second.

History suggests they still have time to get over the top via the BBWAA, but I fail to see the point of making them wait another half-decade or longer. Once the majority of the electorate has spoken in their favor, all that remains is several rounds worth of anxiety-provoking bureaucracy during which the odds increase that a given candidate won't be alive to experience the honor. Meanwhile, individual voters who have held out on such candidates either acquiesce toward consensus or else increasingly make a show of withholding their vote. Neither tendency flatters the process.

Lowering the threshold would have helped Hodges, who reached exactly 50 percent in 1971, though he didn't go over until 1973, the first cycle after his death due to a heart attack. It wouldn't have helped Santo, who peaked in his 15th year on the ballot, then wasn't elected until 2011, almost exactly a year after his death. In such a change, the bar wouldn't necessarily have to be reset exactly at 50 percent; Hodges crossed the 60 percent threshold intermittently during his posthumous eligibility, and of the aforementioned sextet, only Morris has reached 60 percent, so the line could reasonably be set there while still standing as a supermajority of the voting body. Holding 75 percent as sacrosanct just because "that's the way it's always been done" is a lousy excuse; by that same logic, the major leagues could have upheld the color line or failed to allow protective equipment or expansion beyond the "original" 16 teams. In any event, such a change would need not only the BBWAA's stamp of approval but also that of the Hall of Fame, which decreases the likelihood of change happening any time soon.

In the meantime, what's clear is that the voters are faced with a nearly unmanageable task. There's no such thing as a perfect ballot in this mess. If one considers there to be 15 worthy candidates — JAWS+ and Biggio — then 3,003 separate combinations of 10 candidates are possible. Eliminate one (say, Palmeiro, the only one on the ballot suspended for failing a drug test ), and that drops the number of 10-man possibilities to 1,001, still a ridiculous number with which to grapple, and leaving all but the most small-Hall-minded voter with more snubs of worthy candidates than there are likely to be ones elected this round.