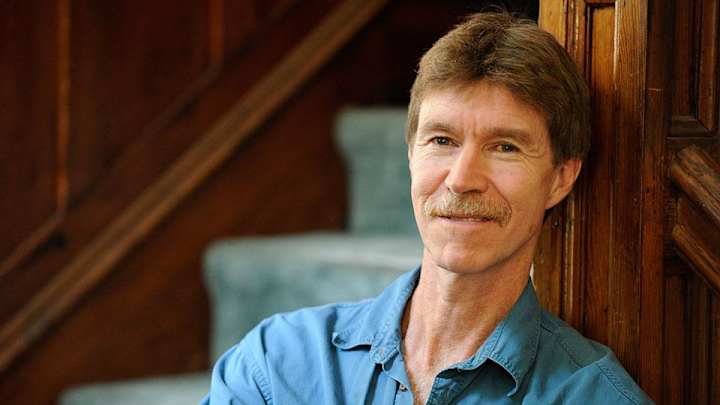

SI 60 Q&A: Gary Smith on John Malangone and 'Damned Yankee'

Even considering the many brilliant stories Gary Smith authored in his 30 years with Sports Illustrated, few made as big an impact as “Damned Yankee,” which appeared in the Oct. 13, 1997 issue. Smith wrote about the journey of John Malangone, a former top prospect for the Yankees who could never escape the tragic event from his childhood in which, at age five, he accidentally killed his seven-year-old uncle. Malangone was so haunted by what happened that he grew up without learning to read, endured flashbacks and other resulting trauma that damaged his personal and professional life until he was almost 60 years old, at which point he was finally able to start the long healing process.

Malangone's life has since become the subject of a documentary and a forthcoming book, but neither of those things would have likely happened if not for Smith’s story, which was a finalist for the National Magazine Award in feature writing in 1998.

Damned Yankee: A dark secret kept John Malangone from fulfilling his promise

SI: This is obviously an incredible story that any journalist would love to tell but it seems you discovered it all alone. How did you find it?

SMITH: The story I wrote about Radio [EDITOR'S NOTE: “Someone To Lean On,” which appeared in the Dec. 16, 1996 issue, would eventually be turned into the movie, Radio, starring Cuba Gooding Jr.] had just come out and Ron Weiss penned me a letter and that basically said, “I just read the Radio story. You’re the guy who needs to write the story about my buddy John.” He just gave me a few details on the page and it was enough for me to think, You’re damn right I do.

SI: Did he get John’s permission to go to you about that?

SMITH: That’s a good question. I’m guessing he got John’s OK but I never asked him that. John was very cooperative with it though. I think he was already seeing the psychological benefit of having told Ron and Ron had taken him immediately to go see his mother and there was this incredibly emotional three hour period that they spent talking about all this. John was already feeling like a piano was off his back, so I think this was just going to be one more step in his healing process.

SI: The story has a happy ending in a way, but John’s troubles, probably as a result of the trauma he suffered, went beyond his baseball career being shortened and extended to other areas as he got older: difficulties in his marriage, multiple jobs, an inability to connect with his children, etc.

SMITH: Yeah, he and his wife had a lot of trouble in their relationship and he could never get close to his kids because he was afraid he was going to hurt them. Underneath all that there’s all kinds of secondary things, like his being afraid of them asking for help with their homework because he couldn’t read. He’s afraid that if all those things tumble out the whole thing will all start to spill. So he was always on the move, never a stationary target, for everyone close to him in his life. It’s all part of this vast coping system that he’s come up to deal with this series of things.

SI: Given all these elements, did you ever consider doing this story even longer, either as multiple parts or as a book? If not, how did you determine which parts of the story to tell?

SI 60 Q&A: Gary Smith on his award-winning morality tale about Richie Parker

SMITH: I always took it as a challenge: Can I compress, compress, compress and get the heart of the story down in 7,000 or 8,000 words? I felt like it would lose some of its power if it was spread out and you had to regenerate that power in the second installment, and maybe people would have missed the first one. It wasn’t something the magazine did that often anyway. It could have been a book but I was always of the type that once I had explored something and spent that amount of time with it, it wouldn’t be worth it to spend another year because I would feel like I was expanding something I already knew rather than learning something new. I was always reticent to blow things out into books.

Someone did do a book on him that’s coming out in early February, though, called Pinstripes and Penance, playing off a book that came out before called Pinstripes and Pennants.

• MORE SI 60: Read every story and Q&A in the series

SI: Where did you find the photograph that is the linchpin of the story?

SMITH: I came up and spent a week or so with John going over to this trailer he was living in, and he pulled this picture out and he told me the tale of how he’d destroyed virtually everything else from his career and there was this one thing he couldn’t bring himself to destroy and there was that picture. It carried so much hope and promise and capturing that moment. It was right when he was getting near to making the Yankees; it was the same spring when Louisville Slugger asked him to sign the form for the signature they’d use with a bat that had his name on it, and it was the same spring he started unraveling and self-sabotaging in a way so he wouldn’t make the Yankees and get into the position he was so fearful of, which was of being found out.

It felt like you could center it around that moment of hope captured in that photograph. It just kind of came together in my mind that that would be an interesting way to write this story and how and why it unraveled form there.

SI: Obviously he hadn’t discussed his story with anyone for over 30 years. Was it hard to get the information you needed from him?

SMITH: It was a great process. He was a sweet person and it was obvious there were things that were tough for him to talk about, but he really wanted to try. He wasn’t dodging at all. He’d been carrying this burden for so long and had finally felt the relief from dropping that burden that he was really in the mode of uncovering and giving over things. He recognized how important that was psychologically to recover. He wasn’t doing therapy. In a way this was perhaps serving that function to tell your story authentically and honestly to another human being. What was amazing was how much humor there was in him, apart from the incredible tragedy.

SI 60 Q&A: Gary Smith on Muhammad Ali, his entourage and memories of the Greatest

What was also remarkable about him—and he became a friend and we’ve maintained contact—every time I’ve talked to him he’s dropped another anecdote I would have died for. I’ll say, “John, why didn’t you tell me that back then?” They’d keep falling like rain, and he’d just throw them out there casually. It was nothing he had been hiding but he just didn’t think of it when we were talking for the story.

SI: Like what?

SMITH: He told me not that long ago that one time he was catching in a minor league game and he kind of blanked out and wasn’t even paying attention and the pitch whistled right over his shoulder and drilled the umpire. The ump was sure he had done it because he was pissed off at his ball and strike calls. The ump got nailed and was in incredible pain and threw John out of the game. It had nothing to do with any of that, of course, it was this thing he was dealing with and how it just made his mind churn and made him blank out.

SI: You used the term “post-traumatic stress disorder” in the story. Did he ever receive professional help for his problem?

SMITH: I don’t think he has. I would have heard if he had gone to anyone in any real way since then. [After the story was published] he got all these letters from people who had similar secrets, big trauma—maybe they couldn’t read or write because of it, or they felt shame that they had held something in and locked [away] that had eaten up their lives—talking about how grateful they were for him telling his story and that now they could tell theirs. After about 60 years of hiding and running now there was a meaning and a purpose to all of that. It had felt like it was just lost time, lost opportunity, but now it was cast in a different light for him. It was such a gift. I’m sure there was still a lot of work he could have done, but this had helped him take a huge step, and of course that’s in conjunction with all that Ron was doing in teaching him to read and being helpful and loving.

SI: So he did learn to read?

SMITH: Ron taught him, so when those letters came in John could read them. That was just another huge piece of all the steps he’d taken in healing. The other was that once his mind was unburdened, what he wanted to do was play baseball, so he joined an old-timer’s league and John pitched them to the World Series title.

SI: Did you show him the story before it was published? What was his reaction when he finally read it?

SMITH: He didn’t see it until it came out, and he seemed very overwhelmed with it. I think he shed a lot of tears over it for the positives. Then we stayed in touch. He’d call me and I’d call him and the relationship continued. He came and stopped by here in Charleston one time on his way down to play in the old-timer’s World Series in Florida. I saw him several times up in the New York area.

SI: Is he still playing baseball?

SMITH: I think he finally stopped. He’s got some physical challenges, and he got a big wallop from Hurricane Sandy that was a really scary event, he almost got swept away in the water. I think he took his dog out for a walk and he described a wall of water coming down the street. His place needed major renovations and he lost a lot of stuff.

SI: Where does this story rank for you?

SMITH: I always thought it was one of the best ones. To me the material was so eye-opening that a human being could go through what he went through—and obviously the event itself was mind-blowing—and how it manifested itself in deep psychological ways: hearing the swish of the javelin and wrapping socks around his ears to block that out; seeing the demon manifesting on cabinet walls; just the extent of what our minds can generate. We write about these things to varying degrees but the extremes of this one were so dramatic that it just felt like the material in this one was maybe richer than any of the stories I worked with.

SI 60 Q&A: Gary Smith on writing 'Higher Education' -- twice

SI: You mentioned before that you were often rewriting stories during this period. Did you have to do that with this story?

SMITH: No, the idea of using the photograph and centering the story around it and coming back to it again and again from different angles idea seemed to work right from the beginning.

SI: If ever there was a story of yours that cried out to be made into a full-length movie, it was this one. Was that ever discussed?

SMITH: Yeah, this one I really thought could be a good movie and there was interest in it but ultimately they finally decided that he sat on this secret for so long and there was all this torture and pain and that made it problematic to work in the Hollywood formula. Even though initially some people were very excited they ultimately all reluctantly passed. They would have had to condense the reality of it where either he finds the light in his 30s so it’s not a lifetime of unremitting angst, or you would have had to do it in flashbacks where you were getting a decent-sized chunk of the good with him as an old man. But then you would have had to condense a lot of the angst, and it would have taken altering it so much that it wasn’t worth going there.

Ted Keith is a senior editor for Sports Illustrated and oversees SI.com’s baseball and college basketball coverage. He is also the co-host of SI.com’s weekly baseball podcast, “The Strike Zone.”