A-Rod's actions going forward will dictate meaning of 660th home run

A home run, an historic number and a cavernous lack of substance. Like below-grade toxins at a superfund site, The Steroid Era knows no end, its poison seeping to the surface as a corrosive reminder. Now it’s time to break out the hazmat suits again.

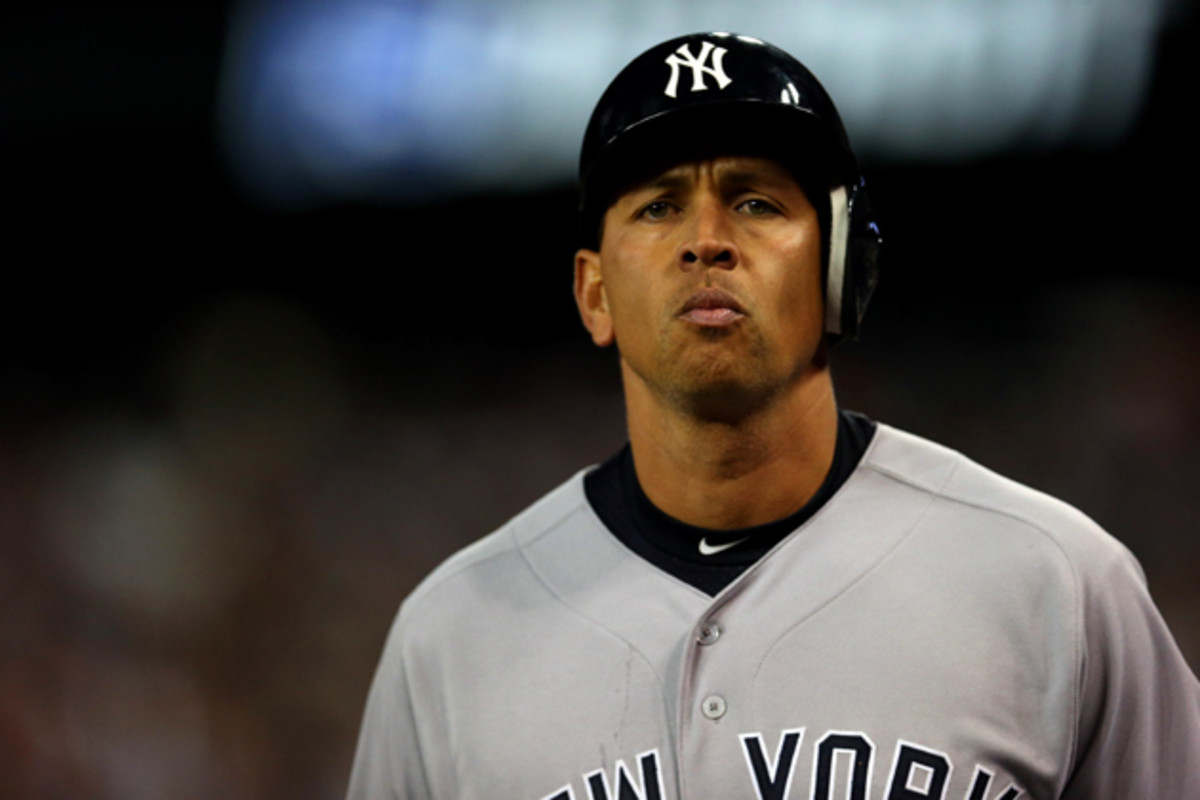

With home run number 660 against the Red Sox on Friday night, Alex Rodriguez has tied Willie Mays for fourth place on the all-time home run list. It’s not a milestone. It’s a quagmire. So many homers, so little authenticity. What celebration it does engender is the celebration of renown, not of achievement. A man of great skill made himself more famous for what he did off the baseball field than on it.

• WATCH: A-Rod belts one over Green Monster for number 660

Rodriguez was supposed to be the next “clean” home run champion, or at least the New York Yankees thought so in 2007, just two days before the Mitchell Report was released, when they couldn’t resist trying to profit off Rodriguez’s pursuit of Mays, Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron and Barry Bonds, a money-grab from which they now try awkwardly to retreat. The legends are safe, no matter how high the home run total climbs. Instead, as a cultural punch line with no welcome baseball harbor, Rodriguez has joined the company of his fiercest rival—a former friend, fellow Miami native and No. 35 on the all-time home run list—who wrote in 2008, “So A-Rod, if you’re reading this book, and I’m not getting through to you, let’s get clear on one thing: I hate your ---- guts.”

*****

On May 14, 2002, on the day after he announced his retirement, Jose Canseco told Dan Patrick he planned to write a book in which he would “name names” regarding steroid use in baseball. Canseco gerrymandered a career of 462 homers by starting a steroid regimen at age 20 after playing Class A ball in 1984. His career ended in 2002, after he hit .172 in Triple A at age 37.

How many home runs would A-Rod have if he had stayed healthy, clean?

On the day of Canseco’s announcement, I happened to be in Chicago, where the Texas Rangers were playing, to talk to Rodriguez about steroids. I was wrapping my reporting on the SI special report on steroids in baseball. When I interviewed him in his hotel suite about steroids, he staged an elaborate theatre of naivete, claiming he knew so little about them he was asking me what they do and why players would take them. Of course, as per his 2009 admission, at that time the perfidious slugger was two years into his steroid use as a Ranger.

It was only in the Rangers’ clubhouse at US Cellular Field that I glimpsed some truth in his eyes. Rodriguez had just heard that Canseco was planning to write a tell-all book. Rodriguez showed genuine concern. He described Canseco to me as a loose cannon because he was out of baseball and had no friends in the game; there was no collateral damage for Canseco to worry about.

It was years later when I could decode the worry on his face. On Dec. 13, 2007, Rodriguez signed a 10-year, $275 million contract with the Yankees that included that $30 million “marketing agreement” for both the club and player to profit off his “milestone” home runs. Just two days later, the Mitchell Report was released, and Canseco, noting Rodriguez’s omission from the white paper, exclaimed, “I could not believe his name was not in the report.” Two days after that, Rodriguez lied to Katie Couric on national television, telling her he never used steroids because “I’ve never felt overmatched on a baseball field.”

• Bonds: Baseball should celebrate A-Rod's 660th

Fifteen months after that, in his second book, Canseco wrote that he introduced Rodriguez to his steroid supplier as long ago as the late 1990s.

“I did everything but inject the guy myself,” Canseco wrote.

And 11 months after that, SI reported that Rodriguez flunked a steroid test in 2003. It took Rodriguez 10 days to come up with an explanatory press conference, and when he did, he kept acting. He stumbled, in a practiced kind of way, on the pronunciation of Boli, the juicers’ term for Primobolan.

Infamously, Rodriguez challenged people to “judge me from this day forward.” Done.

*****

Jose Tolentino outslugged Jose Canseco on the 1984 Class A Modesto A’s. Tolentino went on to hit one major league home run. Canseco, a 15th-round pick two years earlier, returned to his Miami home after that season in Modesto and promptly made himself into a freakish baseball player through steroid use. He reported to camp the next spring with a different body: 25 pounds heavier, muscles bulging and acne on his back.

Canseco had slugged a healthy .446 at Modesto. After his steroid regimen, he slugged a ridiculous .739 at Double A Huntsville. He was transmogrified.

We get lazy with words and truths. In the dawning of 660, today we are told that Rodriguez made “a mistake.” He deserves “a second chance.” He was a great player “before steroids.” He must be “clean now.”

This is why 660 home runs have little authenticity: Rodriguez has been a serial juicer, whose benefits from steroids have both a murky beginning and end.

Book excerpt: Pedro Martinez talks 2003 season, rivalry with Yankees

He ordered drugs from Tony Bosch’s Biogenesis clinic with what he thought was covert skill: cash transactions, code names for himself and his drugs, which Bosch instructed him to take morning, noon and night through injections, creams, pills and troches. It was no “mistake.” It was a sophisticated ruse meant to cheat drug tests, baseball, the fans and fellow competitors. Arbitrator Fredric Horowitz called it “unprecedented,” not only Rodriguez’s violations of the Joint Drug Agreement but also his “misconduct” in obstructing baseball’s investigation. On the heels of Canseco’s timetable, the “Boli” years, the association with Anthony Galea and the Biogenesis years, the scorekeeping of a “second” chance is an amusement.

The great thespian staged an all-time performance on Nov. 20, 2013. At MLB headquarters in New York, where he was appealing his 211-game drug suspension from commissioner Bud Selig, Rodriguez kicked a briefcase, slammed a table, cursed in front of then chief operating officer Rob Manfred and stormed out of the room. It was phony, sure, but it beat the alternative: telling the truth.

Two days later, a group of Norwegian scientists published a study in The Journal of Physiology that is worth recalling with Rodriguez making himself the home run equal of Mays. Their research showed that steroid use boosts cell nuclei in muscle fibers, and suggested that even when an athlete stops taking the steroids, a kind of “cellular muscle memory” provides an enhanced benefit over the athlete who didn’t use steroids.

• REITER: A-Rod's monster night proves he's far from done

“The benefits of even episodic drug abuse,” the researchers wrote, “might be long lasting, if not permanent, in athletes … A brief exposure to anabolic steroids might have long lasting performance-enhancing effects.”

Imagine the long-term benefit of years of cutting-edge drugs, which is why the researchers suggested the World Anti-Doping Agency re-think the two-year ban for dopers: Even after two years they compete with the benefits of steroids. The idea that suddenly there is a “clean” Rodriguez is naïve.

Last summer I was talking to an All-Star veteran about the surprise of how well busted steroid users Nelson Cruz, Jhonny Peralta and Melky Cabrera were playing. He didn’t need Norwegian scientists to see what was happening.

“Don’t be fooled,” he said. “They still have an edge on us. Their bodies were changed. You accrue the benefits for years.”

*****

Rodriguez was right about Canseco. With a pen, he was a loose cannon, so much so that Canseco himself later said he regretted his foray into publishing. Canseco was a bitter man back then, convinced that baseball had blackballed him from another shot, even though five organizations, the Rays, Yankees, Angels, White Sox (twice) and Expos, all gave him a shot in his last three seasons. The baseball door smacked him in his needle-pocked posterior on the way out, never to open again for him.

Here is where Rodriguez dearly wants to separate himself from his former friend. Canseco never loved baseball, he loved what baseball could bring him: wealth, status, attention, fame. Rodriguez loves baseball. Sure, he also loves the spoils it can bring, but he loves it on a micro level: how the game is played and the attention and work required to play it well.

David Ortiz on Cubs' Kris Bryant and why hitting is harder than ever

He watches baseball constantly. He turns 40 this summer. He can’t imagine a life without baseball, somehow, some way. He has begun seeding that post-career life he wants.

It is true that Rodriguez has alienated the three franchises for which he has played: the Mariners, Rangers and Yankees. (He is Seattle’s all-time leader in slugging and OPS, but you won’t find him on its Franchise Four ballot.) But he wants and needs baseball. Privately, ever since Rodriguez took his one-year ban, the commissioner’s office has commended his behavior. Whereas Rodriguez insulted Selig at the arbitration hearing, he has kept an open line with Manfred, Selig’s successor. He wants to do well by Manfred.

To his credit, Rodriguez has been a model post-suspension citizen. He has worked hard, played better than the Yankees had reason to expect and made himself available to the media while choosing the right words and never taking the bait of loaded questions. Reggie Jackson used to pass along advice to Rodriguez that Jackson’s own dad had given him: “As long as you have a bat in your hands, you have a chance to change the story.”

It’s still true for Rodriguez, though not in the manner of changing the story of his baseball reputation. That’s shot for good. He can change his personal reputation. If he can continue to be just about baseball now —not the drugs, not the self-inflicted wounds, not the drama—he can and should have the life in baseball that he wants.

Even after wrapping best April in years, things looking up for Cubs

Mark McGwire, Matt Williams, Manny Ramirez, Jason Giambi, Roger Clemens and Jason Giambi all have been welcomed back, and Barry Bonds, a brilliant hitting mind, deserves a bigger role with the Giants if he wants. Poor decisions as players, hardly outlying ones back in the day, shouldn’t preclude contributions today.

Rodriguez is under contract for two more seasons after this one with the Yankees. The peace of his return could shatter soon if the club and the player go to war over their “marketing agreement” and the $6 million bonus for hitting number 660. The Yankees, rightly furious over Rodriguez’s deception and attacks—he sued the club for tortious interference and the team physician for medical malpractice—believe his steroid use nullifies the marketing value of the “milestone.” Rodriguez is likely to argue the contract does not give specific enough language for that out, and only the commissioner can discipline players for steroid use, and that already has occurred.

An arbitration hearing could be as ugly as the last one, with the Yankees giddy to get Rodriguez on record about his 2009 association with Galea. Ugliness does not suit Rodriguez well at this indemnifying portion of his career. The diplomacy of at least a deferral is in order here. It would be stunning if, given Rodriguez’s cooperation with the commissioner’s office, we get the sideshow of Rodriguez v. Yankees in the middle of the season, a season when Rodriguez wants the off-field spotlight on him extinguished.

Rodriguez’s 660th home run is an event, made all the more interesting, if not slightly scandalous, by his notoriety. If you’re looking for meaning in an historical baseball sense, just keep moving along. It’s not here. But by now we should be O.K. with that, having trudged through the Steroid Era toxins before. We know how Rodriguez got to 660 and we know he’s not going to join Mays in the Hall of Fame. The meaning lies in how Rodriguez moves on from here.