No-no regrets: Johan Santana would not alter a thing. Terry Collins might.

Suppose the devil made you this bargain: You can have one unforgettable night doing what you love to do, but in exchange, you will never again be able to do it nearly as well. Would you take that deal? No? What if he added this: You can bring joy to thousands of people who will be forever grateful to you. But your future will be full of surgeon’s scalpels and solitary workouts in a futile pursuit of what you used to be. Would you sign on the dotted line?

Here’s another, even more difficult question: What if you had to make that choice for someone else?

****

Rain was in the forecast on June 1, 2012, the radar showing that it could pass over Citi Field sometime during the game, which did not bode well for Johan Santana. It is difficult for any starting pitcher to get back on the mound after sitting through a delay, and Santana knew he would not even be allowed to attempt it. It was his 11th start after missing an entire season due to major shoulder surgery, and his left arm was too valuable for the New York Mets to take such a risk. If the weather caused a mid-game stoppage of any length, he would be done for the evening. No one would want to take the chance that he would come back and get injured.

But Santana didn’t concern himself with that as he began to prepare in the Mets' bullpen. Pitching, he often said, was about being in the moment, about clearing your mind of everything except the next pitch. He concentrated instead on the way he felt as he started to throw, lightly from in front of the mound at first, then harder, from a full wind-up when he backed up onto the rubber. Normal. He felt normal. After the months of rehab, of strengthening his arm with elastic resistance bands, triceps extensions, dumbbell flys and dozens of other exercises, after working diligently to regain his velocity and command of his pitches, he didn’t take that feeling for granted.

Before the 2010 surgery to repair a torn capsule in his shoulder, there had been pain when he threw, and afterward, even though the discomfort was gone, the anticipation of it was not. It had taken him weeks to be able to release the ball freely, without worry. But now everything was the way it used to be when he was the best pitcher in baseball, when he won a pair of American League Cy Young Awards with the Minnesota Twins before being traded to the Mets in February 2008 and signing a six-year contract extension worth $137.5 million with them. He had thrown a shutout in his previous start, a four-hitter against the San Diego Padres in which he threw just 96 pitches, striking out seven and walking no one. It was a clean and efficient performance, his best game since he’d been back, and it dropped his ERA to 2.75. The biting of fingernails over Santana’s health had given way to discussion about whether he might make the All-Star team. In a way, it was a good sign that the pre-game crowd for this Friday evening game against the St. Louis Cardinals was sleepy and relatively sparse. It meant that his starts had become routine again, that his excellence was expected.

Tales of Todd Frazier: Reds star emerges as a baseball folk hero

When Santana finished warming up he jogged to the dugout, where he went through his series of elaborate handshakes featuring individualized choreography with each teammate. He was never one of those pitchers who went into an intense, unapproachable cocoon on the days he started; he was gregarious and relaxed until the moment he stepped on the mound, when he became all business.

In the first inning he induced fly balls from Rafael Furcal and Matt Holliday and struck out Carlos Beltran, the former Met whose return to Citi Field for the first time since he was traded away the previous summer was supposed to be the game’s main storyline. But Santana walked David Freese and Yadier Molina in the second, and his fastball seemed to have a mind of its own, refusing to hit his desired spots. In New York's bullpen, Santana’s fellow pitchers were agreeing that he did not have his best stuff, that tonight would be a battle. He managed to escape without giving up a run, striking out Matt Adams and Tyler Greene to end the inning, and then he breezed through the third on nine pitches. Santana could tell the Cardinals' hitters were overeager because his fastball velocity was down around 90 miles per hour. They were jumping out of their shoes to hit the pitch, so he used that to his advantage, getting them to lunge at his changeup.

That third inning went so quickly that outfielder Andres Torres patted him on the knee when came in and sat down in the dugout. “You’re rolling now,” Torres said. “We just need the rain to hold off.”

Santana shrugged. “I’m just gonna pitch,” he said. “Whatever happens, happens.”

****

After managing the Los Angeles Angels and Houston Astros in the 1990s, Terry Collins had been out of the majors until the Mets hired him in 2010 to be their minor league field coordinator, overseeing the skill development of the team’s farmhands. That’s what Collins was doing during spring training at the Mets’ camp in Port St. Lucie, Fla. when he first met Santana. “One day the big club was on the road and I was helping run some drills with the minor-league kids and some of the big league guys who stayed back,” Collins says. “Not everybody was going a full 100 percent, so Johan stopped the drill and said, ‘Hey, if we’re going to do it, let’s do it right.’ He didn’t yell it or scream it, just firm, no nonsense. And I’m thinking to myself, wow, even with the Cy Youngs, the playoff games and everything else this guy has accomplished in his career, every single individual drill is still important to him.”

Ever since, Santana had been an object of Collins’ admiration, and he used the pitcher as an example to the minor leaguers of the kind of work ethic and attention to detail it took to be great. When Collins took over as the Mets’ manager in 2011, he saw the grueling work Santana had done to make it back from the torn capsule. Every major league pitcher who had suffered that injury—including Dallas Braden, Rich Harden, Mark Prior, Bret Saberhagen and Chien-Ming Wang—came back significantly diminished if he came back at all. But Santana was beating the long odds against him, and Collins felt he had been entrusted to be the caretaker of something precious. “He was special,” Collins says. “It was my job to keep him that way.”

For Rangers, Josh Hamilton a bargain that was impossible to see coming

Before the Cardinals game, in his daily session with the local media, someone asked Collins what the maximum number of pitches Santana would be allowed to throw. Somewhere around 110, the manager had said. Maybe 115. Some fans and media felt that Collins overworked pitchers, especially his relievers, but he was determined that would not be the case with Santana.

It’s safe to say that no one in the Mets’ organization rooted for Santana’s success more than Collins, which is why it is ironic that what became the most triumphant night of Santana’s career was for the most agonizing of Collins’s. “It was without a doubt,” he says, “the worst night I’ve ever spent in baseball.”

****

In the great re-thinking of baseball sparked by the sabermetric revolution, any number of traditional statistics—batting average, ERA, pitcher wins—have been devalued, exposed as the incomplete, often misleading measurements that they are. In some ways, the no-hitter is in the same category. On closer examination, it’s hard to see why it’s considered such a grand achievement when, in most cases, it’s nothing more than a well-pitched game sprinkled with a little extra good fortune: A line drive is smoked right at an outfielder; a diving stop by an infielder turns a sure hit into an out; or an umpire mistakenly calls a smash down the third base line foul when it should have been ruled fair.

A no-hitter is more a roll of the dice than a measure of greatness. Chris Bosio threw one but Pedro Martinez did not. Eric Milton threw one but Steve Carlton did not. Bud Smith threw one, but Roger Clemens did not. A journeyman pitcher named Joe Cowley tossed a no-no for the Chicago White Sox in which he walked seven and allowed a run on a sacrifice fly. The quality of a no-hitter can vary so widely as to make the term in and of itself almost meaningless. And yet…

“Every pitcher wants to do it at least one time,” Santana says. “There’s something about it, the way you never see it coming. Once you start to get close, can you make the pitches you need to finish it? But mostly it’s the surprise. The surprise makes it special.”

The randomness helps give the no-hitter its mystique. By the late innings, everyone in both dugouts and in the stands is fully invested. You will either get the perfect payoff to all that anticipation … or it will all come crashing down at the finish.

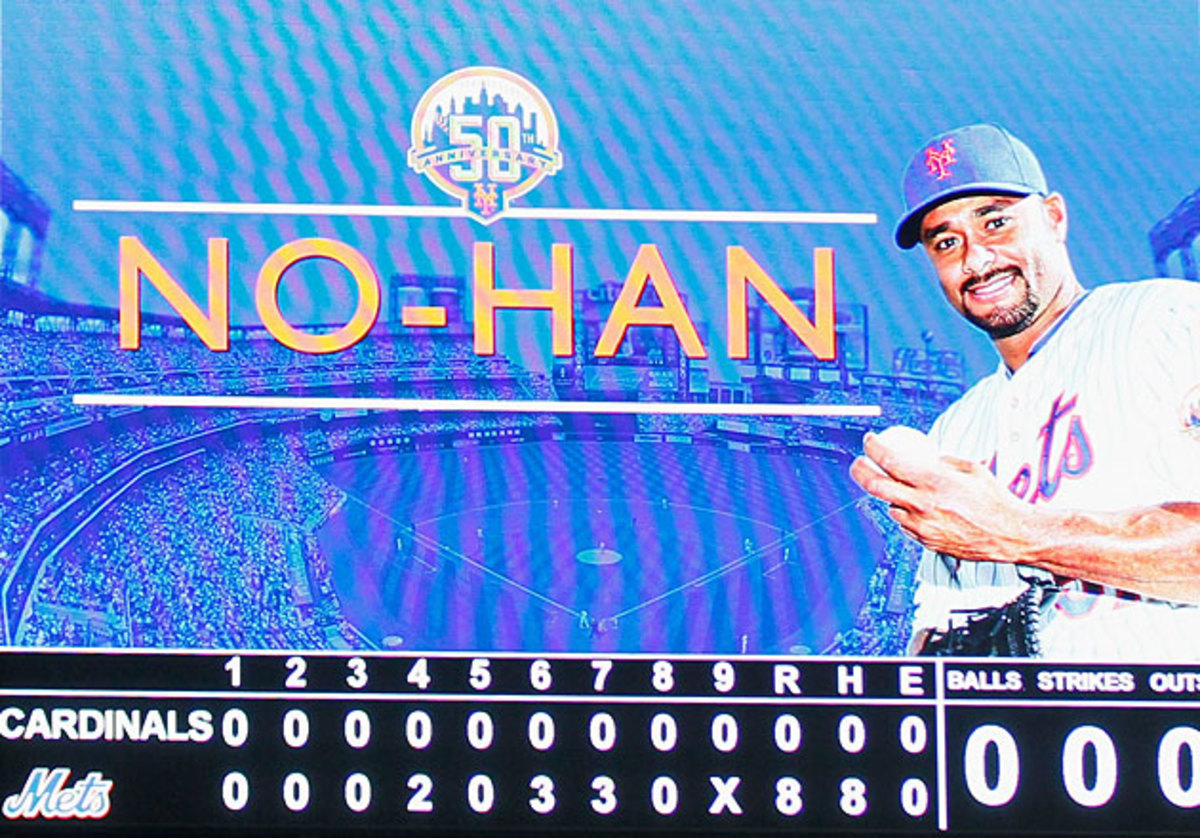

For the Mets and their fans, that ending had always been the same. Since the team’s birth in 1962, that extra dash of good no-hitter luck had eluded them. For five decades the Mets had watched other teams’ pitchers get kissed by good fortune. When Santana took the mound against the Cardinals, the franchise had played 8,019 games without a no-hitter. The Padres were the only other team without one, but their franchise was seven years younger. The inability of the Mets to get a no-hitter, especially in light of how many great pitchers they had produced—Tom Seaver, Dwight Gooden and David Cone among them—was proof that God was not a Mets fan.

Any fan worth his psychosis knew about the no-hitter drought. In 2008, Mets fan Dirk Lammers, an Associated Press reporter, started NoNohitter.com, a blog devoted to the team’s pursuit of a no-no. One of Lammers’s earliest baseball memories was Seaver’s no-hitter for the Cincinnati Reds in 1978. Seaver had pitched 10 spectacular seasons for the Mets before his trade to Cincinnati in '77, and in that time he had pitched five one-hitters, including the most famous Mets near-miss of them all, the 8 1/3 perfect innings he pitched against the Chicago Cubs before a little-known outfielder named Jimmy Qualls broke it up with a single with one out in the ninth. A year and one day after Seaver joined the Reds, he finally threw the no-no. Of course.

“I was nine, and I remember thinking, That should have been the Mets,” Lammers says. “I remember Gooden coming close for the Mets and the David Cone one-hitter. Then Gooden threw one and Cone threw one, a perfect game, actually, both for the Yankees. The Yankees. It was like, ok, this is officially a curse.”

That was bad enough, but then Lammers discovered that the Montreal Expos, founded in 1969, got their first no-no only nine games into their existence. “I was like, oh, come on,” he says. Lammers didn’t realize how many Mets fans believed in the curse until he started the blog. “I thought it was only me and a few friends who were desperate for this thing to end,” he says, “but it turned out it was pretty much everyone who ever rooted for the Mets.”

****

In the fourth inning Santana allowed a walk to Holliday but nothing else, and the Cardinals continued to help him by swinging early in the count. After throwing a total of 40 pitches in the first two innings, his pitch count was at a more manageable 61 after four.

That was about the time Kevin Burkhardt, then the Mets’ roving reporter during their local telecasts on SNY, noticed the zero on the scoreboard under the Cardinals’ hit column. “He didn’t have good control,” Burkhardt says. “He was just kind of getting through it. But after the fourth, I was like, ‘wait a minute.’ He got more intense, laser sharp.” Santana opened the fifth by issuing his third walk, to Adams, before striking out Greene and Adam Wainwright and retiring Furcal on a line drive to left.

When Santana took the mound for the sixth inning, the no-hitter buzz was beginning in earnest. This being the Mets, there was a subtext of pessimism. Who would break it up? The despised Molina, a longtime Met tormentor whose ninth-inning homer in Game 7 beat them in the 2006 NL Championship Series? Beltran, who had spent six-plus mostly brilliant years in centerfield for the Mets which somehow never seemed good enough for a portion of the fan base? Beltran was leading off the sixth. Yes, it would probably be Beltran.

Sure enough, Beltran pulled a scorching ground ball past third baseman David Wright, and for a moment, the magic went out of the night. It was all over. But third base umpire Adrian Johnson threw his hands in the air signaling foul ball. After the game he would see what the television audience saw on replay, that the ball had clearly nicked the foul line just after it went past the bag.

“Did it?” Santana says now, winking. “I’m still not sure.” Given that reprieve, he retired Beltran on a ground out in a 1-2-3 inning.

“I started to believe after the Beltran grounder, after the … I never like to say it was a blown call,” Lammers says. “I wasn’t there. I can’t say for sure. And then, after Mike Baxter went into the wall for that catch.”

No Met player understood more about what a no-hitter would mean to the fan base than Baxter, who grew up in Queens in the shadow of Shea Stadium. His father, Ray, makes the six-minute drive to the ballpark to see every Mets home game, and was in the stands to see his son preserve Santana’s gem by crashing headlong into the leftfield wall to gather in Molina’s fly in the seventh inning. It cost Baxter a displaced right collarbone, fractured rib cartilage and two months on the disabled list.

Like Santana, Baxter had a hard time getting back to normal after his injury. The Mets waived him in 2013 and he was picked up by the Dodgers, who released him after the '14 season. He then signed a minor-league contract with the Cubs, who called him up to the majors this May. “I can’t say that the injuries slowed my career down, but obviously they didn’t help,” he says. “But regardless, it was worth it to be able to not only be there for the no-hitter, but to be a part of making it happen.”

****

Santana is in Florida again, at the Toronto Blue Jays’ facility in Dunedin, not unlike the one in Port St. Lucie where Collins first met him five years ago. The Jays signed him in March to a $100,000 contract and brought him to spring training with the understanding that it would take weeks before he was ready to pitch in even an exhibition game. Maybe Santana’s arm will cooperate enough for him to get major league hitters out again, or maybe not. There are no expectations, no timeline.

Still, there is no denying the progress has been slow. On this day in April, Santana is throwing from 45 feet. He has not even advanced to throwing from the mound yet.

Once the Mets exercised the $5.5-million buyout clause in his contract after the 2013 season, Santana remained unsigned until the Baltimore Orioles gave him a contract in March 2014. He pitched well in spring training—until he snapped his Achilles tendon. So he went home to Venezuela, and typical of his optimistic nature, he considers that a blessing in disguise because it gave him more time to spend with his family. He pitched in winter league to see if he still had the passion, the desire to try for another comeback, and he quickly discovered that the fire was still there, even as he also experienced more shoulder soreness requiring still more rehab. His agent, Chris Leible, put out the word that Santana still wanted to pitch, and after several teams looked at him, the Blue Jays finally made him an offer.

There is no way to say with any certainty that the 134 pitches Santana threw on that night caused the three years of struggles that have followed it. Maybe his arm was destined to break down on him no matter what he did. For Santana, that uncertainty is comforting.

“You can’t say it was the right decision or the wrong decision,” he says. “Because you don’t know. No doctor ever told me, ‘Oh, if you didn’t throw so many pitches in this game or that game, your shoulder would not have been hurt again.’ Maybe if I would have gotten knocked out in the fourth inning, everything would have been different, or nothing would have been different.”

Unbelievable May suggests Bryce Harper's breakout has finally begun

But there is no denying that something changed after June 1, 2012. In his next start, Santana was shelled by the Yankees, giving up four home runs in five innings in a 9–1 loss. Next came another five-inning start in which he surrendered four runs and labored through 96 pitches. He then had a stretch of several decent outings, but only got past the sixth inning once the rest of the season, when he held the Dodgers scoreless for eight innings on June 30. That game would prove to be the most recent win of his career, and the aberration in a horrid second half in which Santana had an 8.27 ERA in his final 10 starts. After he gave up 15 hits and 14 runs in a total of 6 1/3 innings against the Braves and Nationals in August, the Mets decided to shut him down. “My arm felt more or less OK, but then I got inflammation in my lower back,” says Santana. “Then you start overcompensating and it goes to your shoulder and your knees, and they decided to shut me down for the year.”

The following spring, it didn’t take long to see that Santana still wasn’t throwing smoothly. An MRI revealed that he had the same torn capsule injury as before, and he never threw another pitch for the Mets.

****

When Santana finished the seventh inning, he had thrown 109 pitches. The fans in Citi Field were all in now. The weather had cooperated—a light rain had come and gone—and now there was just the exquisite agony of hoping for a no-hitter.

For Collins, there was only agony. He was torn, a part of him hoping that a Cardinal would bloop in a hit so he could pull Santana. “I don’t know if I said it, but I thought it,” Collins says.

He went to Santana after the seventh and got the expected response. “I can do this,” Santana told him. “I’m fine.” Collins looked at him and said, “You’re my hero.”

“Thanks,” Santana said. “Now go over there, because I’m not done working.”

Collins talked to pitching coach Dan Warthen at the end of the dugout, and they decided they would have to let Santana make the decision. Every foul ball made Collins wince. Another pitch, and another. Everywhere there were mini-debates going on about whether Santana should be allowed go so far past his 115-pitch limit. “We’re all down in the bullpen asking each other, ‘Is he going to take him out? Is he going to leave him in?’” pitcher R.A. Dickey says. “‘Would you take him out, leave him in?’ I don’t remember a single guy saying pull him. It was one of those moments. You have to let him go for it.”

Collins felt the same way, but that didn’t make it any less torturous to watch. “I was just sitting there hoping he’ll get a couple of one-pitch outs,” he said. “I was very aware of what the wear and tear of that night could do to him, and basically, that worst-case scenario happened. To throw that amount of pitches with that much pressure and that much adrenaline going, it can beat you down. And it did.”

In the ninth, Holliday lined to center and Allen Craig flied to left, leaving Freese as the only man between Santana and the no-hitter. The count went to 3–0, then a strike, then another. Santana went back to his money pitch, the changeup, pitch 134.

Freese swung and missed. It was done.

In the bedlam, after catcher Josh Thole had jumped into Santana’s arms, after he had been mobbed by his teammates, while 27,609 disbelieving fans chanted his name, Santana went into the dugout, where Burkhardt was waiting to interview him. “He hugged me and he just started crying,” Burkhardt said. “All that he’d overcome, it just hit him. He knew what it meant to the fans here. It meant even more because of the Mets’ history and he realized that.”

But was it a good trade, the no-hitter for, possibly, more healthy seasons? “If you had to choose, maybe you’d take more years, maybe you’d choose getting to the postseason,” says Burkhardt, “but it’s close.”

“I think about that a lot,” says Lammers, the superfan. “If someone had offered me the choice: You can either have a no-hitter or Santana can pitch this many more games for the Mets … well, I’m glad I’m a fan and not sitting in the dugout as a manager. The choice would be that close. I don’t know which way I’d go.”

Collins has his wife’s ticket stub from the game, autographed by Santana, framed in his home. It may have been the worst night of his career, but it’s still one he never wants to forget. “People still come up to me at banquets, on the street, wherever, and tell me they’re glad I let him finish it,” Collins says. “I’m glad they’re glad. For me, the one thing it did is that one of the great competitive players I’ve ever been around got to have a great moment, and I was very happy for him.”

As Santana left the clubhouse after the no-hitter, a security guard approached him. “He just gave me a hug and said that was from his dad. He said his dad was a Mets fan from Day 1, and he thought he’d never see a no-hitter, and he told him, ‘Give Santana a hug.’ I mean, that’s pretty emotional, right? Pretty special.” Santana wrapped his arms around the security guard, embracing the man and the moment, not the slightest bit worried about whatever would happen next.

****

It’s unlikely that Santana will ever have another night on a major league mound that rivals the no-hitter, but that isn’t even his goal. “Just to be on a mound again in the big leagues, that’s all I want,” he says. “It doesn’t matter how. Starting, relieving, just to pitch again. Coming back is a challenge and I love challenges. Is it going to happen? I don’t know. But I’m taking my chances and I’m giving it everything I have.”

He has no regrets about anything that happened on that June night three years ago. “It’s easy to criticize things after they happened,” he says. “You don’t have a crystal ball to say what’s going to happen. I told Terry I felt fine, and I did. Even if an army had come to get me, I wouldn’t have come out of the game. I love this game too much.”

Santana knows that Collins still struggles with the decision he made that night. “Tell Terry he’s a great manager and everything is fine, I’m fine,” he says. “There’s nothing for anybody to be sorry about. What happened, happened.”

When those words are relayed to Collins, he is asked whether they help him feel more at peace with his choice. He allows himself a small smile.

“Not really,” he says.