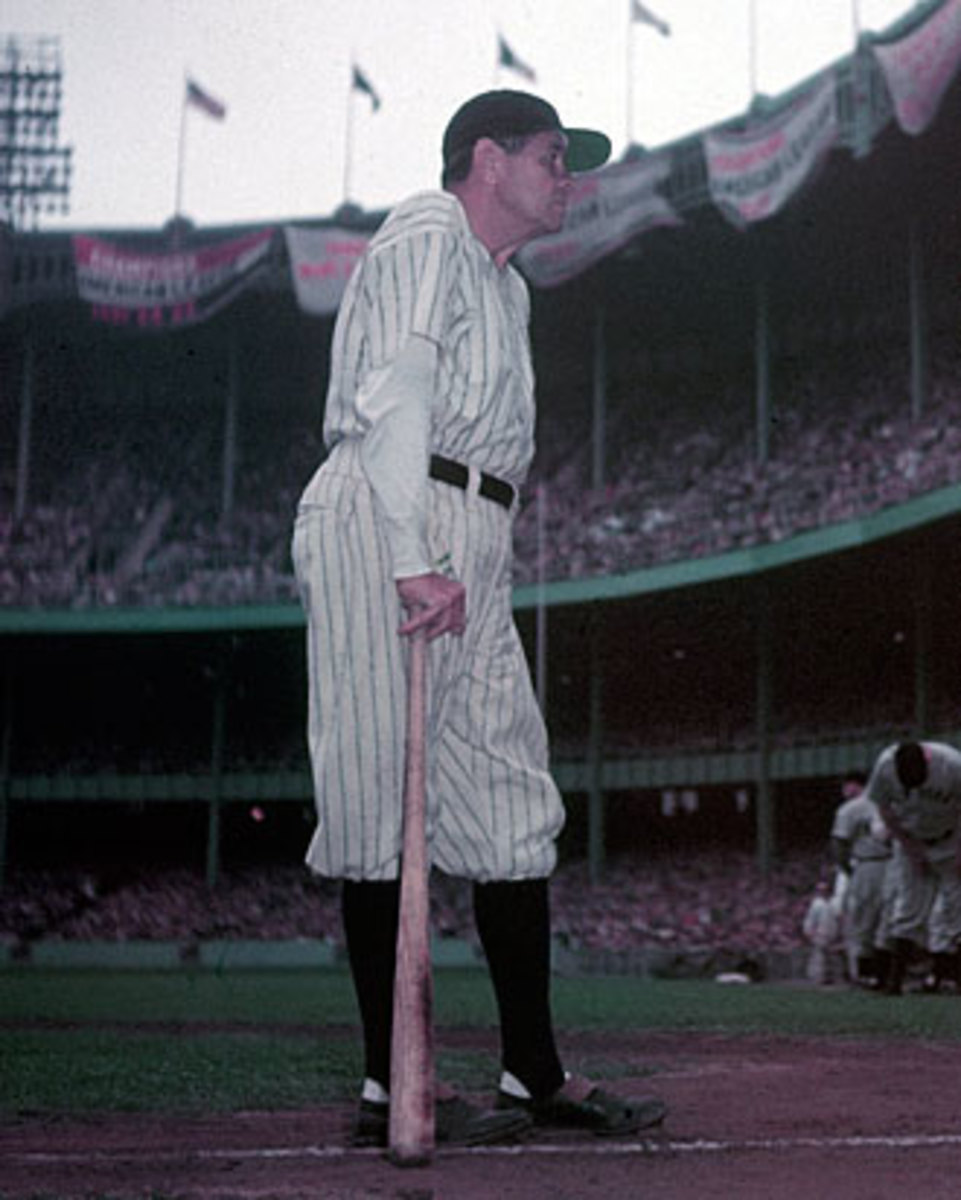

Down Memory Lane With The Babe: Ruth says goodbye to Yankee Stadium

The following is an excerpt from Top of His Game: The Best Sportswriting of W. C. Heinz, edited by Bill Littlefield and published in hardcover and e-book by The Library of America. It is reprinted here by permission of Gayl Heinz. For more information, or to buy a copy of the book,click here.

The column, by legendary sportswriter W.C. Heinz, is entitled "Down Memory Lane with the Babe" and was originally published in the New York Sun on June 14, 1948.

The old Yankees, going back twenty-five years, were dressing in what used to be the visiting clubhouse in the Yankee Stadium, some of them thin, some of them stout, almost all of them showing the years. Whitey Witt was asking for a pair of size-9 shoes. Mike McNally, bending over and going through the piles of uniforms stacked on the floor, was looking for a pair of pants with a 48 waist.

“Here he is now,” somebody said, but when he said it he hardly raised his voice.

The Babe was the last to come in. He had on a dark suit and a cap oyster white. He walked slowly with a friend on either side of him. He paused for a moment and them he recognized someone and smiled and stuck out his hand.

They did not crowd him. When someone pointed to a locker he walked to it and it was quiet around him. When a few who knew him well walked up to him they did it quietly, smiling, holding out their hands.

The Babe started to undress. His friends helped him. They hung up his clothes and helped him into the parts of his uniform. When he had them on he sat down again to put on his spiked shoes, and when he did this the photographers who had followed him moved in. They took pictures of him in uniform putting on his shoes, for this would be the last time.

He posed willingly, brushing a forelock off his forehead. When they were finished he stood up slowly. There was a man there with a small boy, and the man pushed the small boy through the old Yankees and the photographers around Ruth.

“There he is,” the man said, bending down and whispering to the boy. “That’s Babe Ruth.”

The small boy seemed confused. He was right next to the Babe and the Babe bent down and took the small boy’s hand almost at the same time as he looked away to drop the hand.

“There,” the man said, pulling the small boy back. “Now you met Babe Ruth.”

Book excerpt: Ty Cobb ruled baseball, until Babe Ruth stole his spotlight

The small boy’s eyes were wide, but his face seemed to show fear. They led the Babe over to pose him in the middle of the rest of the 1923 Yankees. Then they led him into the old Yankee clubhouse—now the visiting clubhouse—to pose in front of his old locker, on which is painted in white letters, “Babe Ruth, No. 3.”

When they led him back the rest of the members of the two teams of old Yankees had left to go to the dugouts. They put the Babe’s gabardine topcoat over his shoulders, the sleeves hanging loose, and they led him—some in front of him and some in back in the manner in which they lead a fighter down to a ring—down the stairs and into the dark runway.

They sat the Babe down then on one of the concrete abutments in the semi-darkness. He sat there for about two minutes.

“I think you had better wait inside,” someone said. “It’s too damp here.”

They led him back to the clubhouse. He sat down and they brought him a box of a dozen baseballs and a pen. He autographed the balls that will join what must be thousands of others on mantels, or under glass, in bureau drawers, or in attics in many places in the world.

He sat then, stooped, looking ahead, saying nothing. They halted an attendant from sweeping the floor because dust was rising.

“I hope it lets up,” the Babe said, his voice hoarse.

“All right,” somebody said. “They’re ready now.”

They led him out again slowly, the topcoat over his shoulders. There were two cops and one told the other to walk in front. In the third-base dugout there was a crowd of Indians and 1923 Yankees and they found a place on the bench and the Babe sat down behind the crowd.

“A glove?” he said.

“A left-handed glove,” someone said.

They found a glove on one of the hooks. It was one of the type that has come into baseball since the Babe left—bigger than the old gloves, with a mesh of rawhide between the thumb and first finger—and the Babe took it and looked at it and put it on.

“With one of these,” he said, “you could catch a basketball.”

They laughed and the Babe held the mesh up before his face like a catcher’s mask and they laughed again. Mel Allen, at the public-address microphone, was introducing the other old Yankees. You could hear the cheering and the Babe saw Mel Harder, the former Cleveland pitcher, now a coach.

“You remember,” he said, after he had poked Harder, “when I got five for five off you and they booed me?”

“Yes,” Harder said, smiling. “You mean in Cleveland.”

The Babe made a series of flat motions with his left hand.

“Like that,” the Babe said. “All into left field and they still booed the stuff out of me.”

The Babe handed the glove to someone and someone else handed him a bat. He turned it over to see Bob Feller’s name on it and he hefted it.

“It’s got good balance,” he said.

“And now—” Allen’s voice said, coming off the field.

They were coming to cheer the Babe now. In front of him the Indians moved back and when they did the Babe looked up to see a wall of two dozen photographers focused on him. He stood up and the topcoat slid off his shoulders onto the bench.

“—George Herman,” Allen’s voice said, “Babe Ruth!”

The Babe took a step and started slowly up the steps. He walked out into the flashing of flashbulbs, into the cauldron of sound he must know better than any other man.