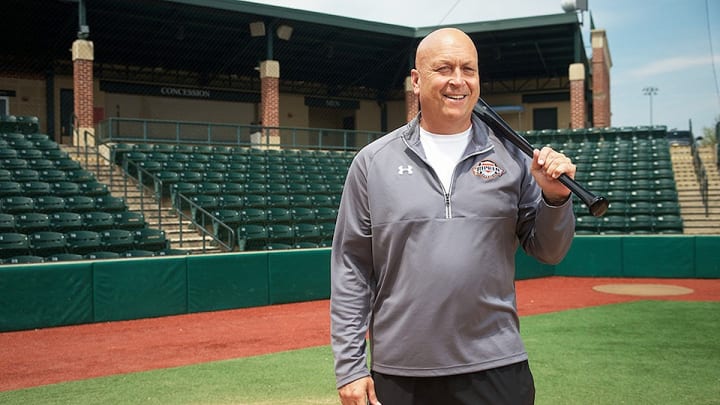

Ever the competitor, Cal Ripken Jr. not resting on laurels in retirement

Even a casual baseball fan knows the adjectives that describe the career of Hall of Fame shortstop Cal Ripken Jr. Words like accountable, dependable, diligent all apply. That’s common knowledge. Ripken’s most famous achievement, of course, was playing in 2,632 consecutive games, which surpassed Lou Gehrig’s streak of 2,130, long considered an unbreakable record.

So it will probably come as no surprise that those same words apply to Ripken and what he’s done with his life since retiring from the game 14 years ago. He created the Cal Ripken Sr. Foundation in his father’s honor and has made it his mission to use the game of baseball as a social tool. At first, most of what Cal Jr. and his brother Billy did was teach the game to kids. But over time, they both saw the possibility to do more. That’s when another adjective that was also used to describe Ripken the player also became applicable. The word: “competitive.”

Fast forward to Tuesday, Sept. 29 in Chicago. The Cal Ripken Sr. Foundation, along with Under Armour and the Chicago Cubs will cut the ribbon on a new synthetic turf baseball field. It will be the 50th inner-city field the foundation has helped to build in the last four and a half years. What’s important about the timeframe is that Ripken—ever the competitor—set a 50-in-five goal. The fields typically require at least $1 million in funding, which the foundation raises through donations. Chicago’s Union League and Boys & Girls Club will be the benefactors of this new facility.

• MLB playoffs: Standings, postseason odds and magic numbers for teams

“It doesn’t seem real to me,” Ripken said in a phone interview last week. "I thought the goal of 50 fields in five years was a ridiculous goal. It was almost like we wanted to see how far we could fall short. But we created a momentum and once we started creating the fields, we got on a roll and we will have gotten it done in four and a half [years]. We couldn’t be more proud of our guys. It’s a wonderful accomplishment. One that we never thought we’d get to.”

The fields serve as home diamonds for youth baseball development programs. So far, they’ve been built in 16 states and there are more to come, in some of the country’s toughest neighborhoods.

“We had workers shot at in Minneapolis,” said Steve Salem, the executive director of the foundation. “Their equipment had bullet holes in it. We’ve had some real challenges, but the more difficult the challenges were, the more important they became to us. We never said we have no chance in those bad locations. It was more like we have to do it here. And we have.”

Ripken says he’s witnessed civic pride in the areas where they’ve gotten fields built. When there’s been a threat of vandalism or violence, neighborhoods have rallied to protect the parks.

“There’s sort of a territorial stronghold that the community puts on it," Ripken says. “These fields are beautiful and the community doesn’t want to surrender to the wrong element. We’ve seen them put up a barrier that then seems to increase the footprint of the area. Ultimately, the kids feel safe playing on these fields and healthy things come out of it, which makes us feel really proud.”

The impetus for the five in 50 goal, Ripken says, came from a woman named Doris Buffett in Fredericksburg, Va. A noted philanthropist in the area (her brother if Warren Buffett), Buffett challenged Ripken.

“We were getting involved in some programs and Doris wanted to build some fields,” Ripken recalls. “She had a grant with her own foundation and told us she’d give us a million dollars for fields if we could come up with the same amount. She wanted to build fields together. We took the challenge and soon realized there was a need for these safe places. These are transformational and they do have a positive effect on the whole area, not just the area that we develop. I think Doris showed us that there was a need.”

Ripken actually completed his first inner-city field project in Baltimore on the site of the old Memorial Stadium as they were raising the funds for Fredericksburg. He says he knew immediately this was the direction he wanted to take the foundation.

“During my career I’d spoken to teammates about why baseball was losing interest in the inner cities and what could be done about it,” Ripken says. “I don’t have all the answers, but here’s what we’ve done. We’ve matched good caring people in the community with kids who need them, through baseball. The inspiration for me actually comes from my dad. When he was managing in the minor leagues he’d give free clinics on Saturday mornings. I would always tag along. He’d go into areas where there was a need and get in front of those kids. I witnessed that firsthand.”

Through a program called Badges for Baseball, Ripken has also gotten local law enforcement officers involved, not policing the area, but coaching the kids. In the aftermath of the Freddy Gray incident in Baltimore, it’s not lost on Ripken that this program needs to be enhanced.

“Going into these areas is less about baseball and more about helping these communities,” Ripken says. “We always understood the need to build the relationship between law enforcement and kids in these communities, so we were working on this long before what happened in Ferguson (Mo.) and Baltimore. When these law enforcement officers come in and volunteer and help kids on the baseball field there’s an immediate rapport that’s developed. They’re good-hearted volunteers who begin to be seen as the good guys, not the bad guys.”

Says Mary Ann Mahon Huels, the President and CEO of the Union League and Boys & Girls Club of Chicago, “The Badges for Baseball grant they provide us offers us the opportunity to engage police officers, firefighters and agents from the FBI and U.S. Marshals Office as coaches and mentors as we keep youth physically active. There’s no doubt in my mind that this field will build new levels of interest and engagement in baseball on Chicago’s South Side.”

When the ribbon is cut on Tuesday, Ripken will sit back for moment and watch the kids play and enjoy the facility. And then, in typical Ripken fashion, he’ll get back to work.

Everyone knows, that’s Cal Ripken Jr.