Excerpt: Sandy Koufax, Maury Wills and the Dodgers in 1960s America

Download the new Sports Illustrated app (iOS or Android) and personalize your experience by following your favorite teams and SI writers.

The following is adapted from the new book The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers, written by Michael Leahy and published by HarperCollins. Copyright 2016. To purchase a copy, click here.

Most men must wait for their chance in baseball, as in life. The wait ruins many. Some succumb in the minor leagues to despair, a few to drink or drugs, the rest usually to an erosion of talent and will. Even for the minor league lifer doing everything right, it becomes increasingly difficult to believe that his dream will ever be realized. It is hard to keep holding on.

In defiance of time, the smallest of players in this locker room has clung to the dream. He waited nearly all of the 1950s in the minors. Everything in a baseball life that matters has come to him late. It makes what is happening to him at this moment in 1962 a tad surreal. This small, lithe, light-skinned black man, once nothing more than a journeyman minor league shortstop, once so little regarded that his own organization sought to trade him away, sits in the locker room at Dodger Stadium, suddenly a national celebrity. Life has never been so exhilarating. Wherever he goes in Los Angeles, people clamor to be introduced to him. Entertainers want him on their television shows. He is closing in on the greatest season of his career, on the brink of breaking a hallowed major league record held by a baseball immortal, Ty Cobb.

A measure of Maury Wills’s new fame can be found in the pile of mail strewn in his locker. Alongside the pile sits a close friend, Sandy Koufax, on the brink of becoming baseball’s greatest pitcher. It says something about the America of 1962 that Koufax is opening and reading Wills’s mail, and that Wills pores over Koufax’s. It says something about the country that each man knows it’s smart not to run the emotional risk of reading his own mail.

A black and a Jew, the two men are united in wanting to protect each other. Some of the letters are just too hateful, too ugly, to be read aloud. Koufax thinks he can anticipate the ugliest by the crude pencil-scribbled addresses and big crazy-looking block printing on some envelopes. “Oh, here’s one you don’t want to read, Maury,” he says, scanning a letter, ribbing his friend a little, laughing, trying to keep the mood light about a subject that has worried both in the past, especially as Wills gets closer to breaking Cobb’s 47-year-old single-season stolen base record.

It will be another 12 years before Henry Aaron breaks Babe Ruth’s lifetime home run record. Wills is the first black man in history poised to take a cherished baseball record away from a white legend. Some racists around the country can’t take it, sending these anonymous missives that make no secret of their hope to see him fail, even be harmed. No danger is inconceivable during that volatile year. Civil rights workers have been beaten that summer during sit-in protests and marches in the South. The imminent court-ordered enrollment of a black student named James Meredith at the segregated University of Mississippi will spark a white riot on campus that leaves two dead. Wills tries staying focused on the game.

The two friends open more envelopes. Wills comes upon yet another anti-Semitic letter meant for his friend, returning Koufax’s gentle teasing over notes to be avoided. “You don’t want to read this one, Sandy.” Wills chortles. “This guy is serious.”

No story about the Los Angeles Dodgers of the early and middle 1960s is complete without focusing on the one who needed to win most, the one who would go to virtually any maniacal length to do it. The one who would—and did—throw a ball between the eyes of an onrushing San Francisco Giants baserunner and knock him out cold. The one who sharpened the spikes of his running shoes with a file before intentionally sliding into a Milwaukee Braves foe, slicing up his knee. The one who, in a moment of intense frustration, actually burst into tears once on the field after an umpire’s call had gone against him.

By 1962 his teammates viewed Wills as the Dodgers’ fiercest competitor. He was their lineup’s leadoff man, their offensive catalyst, their demanding on-field leader, and their hardworking, often tormented dynamo, capable of inspiring many of them even as he sometimes infuriated others.

The frenzy of his record-breaking 1962 season exposed the full range of his emotions, his ecstasy in moments of great victory and his fury when a teammate’s mistake or a foe’s rough play damaged the Dodgers’ standing or his own pride.

Throughout the season, he and Koufax have spent hours talking after games as each man receives treatment—Wills for his bruised and hurting legs, and Koufax for chronic pain in his pitching arm. For months the 29-year-old Wills coped alone with his hate mail. Finally, it became too much. He took a chance and began showing the letters to Koufax, something he hasn’t done with anyone else on the team.

The mania about the stolen base record had only grown. Much of America, Wills thought, evidently believed he had a greater chance than ever of breaking the mark; the volume of mail and its intensity of passions had both risen, judging by how often Koufax winced when he read some letters. Now and then Wills shared his pain about the hate with Koufax, more grateful than ever that his reticent friend made time to listen to him.

None of these conversations would ever have happened if he didn’t so admire Koufax’s character on the mound, a quality that Wills viewed as distinct from Koufax’s talent. Behavior in the immediate aftermath of a bad break revealed character, Wills believed. He had felt wounded a few times by certain Dodger pitchers, who, whether intentionally or not, lost their cool in the heat of some games and disgustedly kicked the mound after he made an error. By contrast, Koufax had a habit of comfortingly looking at him after a miscue, slightly raising his glove in a manner that signaled to his friend that all was okay—everything would be just fine. In return, a grateful Wills soon found himself playing harder behind Koufax than any other pitcher, diving for grounders and liners with an abandon that he couldn’t afford in every game without risking injury.

What accounts for a bond between men? Wills wonders. They rarely hang out together away from stadiums. Each is a born compartmentalizer, their friendship largely confined to locker rooms and baseball diamonds. But their intense mutual admiration and shared zeal for winning has made them close, especially in these postgame hours when Wills benefits from Koufax’s soft-spoken observations, less direct advice than subtle reassurance that things will be all right; that each has the other’s back; that the strangeness of their lives is simply a function of the game, as is the craziness of some fans, media and baseball management. “Here’s another letter you don’t want to read, Maury,” Koufax adds.

The pitcher leaves it at that, falling quiet. He is often the shell that closes as quickly as it opens. Long accustomed to his friend’s reserve, Wills laughs, and they’re done for another night.

*****

The Homecoming

In his relentless drive, Wills felt his stresses mounting. In its intensity, so much about the season, both the good and bad, had added to his pressures. One of the year’s high marks came when the National League tapped him to play in the All-Star Game, and he returned to his native Washington, DC, the site of the first of two All-Star games that year.

It was a triumphal and emotional homecoming. For a while, it had the quality of a wonderful dream. He saw members of his family and signed autographs for local children in whose eyes he saw the same awe he had once reserved for his favorite players in the city.

On the day of the game, he didn’t travel on the National League team bus to the stadium. Instead, spending part of the morning with his family, he rode to DC Stadium with a friend, who dropped him off at a gate in front of the players’ entrance.

There, a security guard denied Wills entry, refusing to believe he was a player even after Wills gave his name and showed the guard his Dodgers gear bag.

“Get outta here, boy,” the security guard said.

Wills said he couldn’t leave. He was a player.

“Get outta here. I’m not gonna say it again. You don’t belong here, boy.”

“I’m a player.”

“I told you to move, boy.”

It had been a while since a white man called him “boy.” Wills pleaded with the guard to summon a National League official or player. Finally, a stunned National League official recognized Wills and swiftly ushered him into the clubhouse.

The rest of the day went well. President Kennedy threw out the honorary first pitch from his box seat near the dugouts. Wills didn’t enter the game until the sixth inning, when he pinch-ran for the legendary Cardinal Stan Musial, promptly stole second base and soon scored the first run of the game. Then Wills led off the eighth inning by singling against Cleveland’s Dick Donovan. When Giants third baseman Dick Davenport followed by lining a sharp base hit on a couple of hops to Detroit leftfielder Rocky Colavito, Wills made an unusually wide turn at second base, trying to tempt Colavito to throw behind him to the Yankees’ second baseman, Bobby Richardson.

Bret Boone on his little brother's big blast in the Bronx to win 2003 ALCS

It was a sucker play, a favorite Wills ploy. Colavito took the bait, gunning a throw to Richardson as Wills dashed toward third base in a bold baserunning move that American Leaguers, accustomed to a brand of ball that featured many sluggers but few speedsters, seldom saw. Richardson made a quick throw to third, but Wills beat it, diving past a protesting Brooks Robinson. The National League’s next hitter, the Giants' Felipe Alou, hit a fly ball into foul territory down the rightfield line. From the time the ball left Alou’s bat, it looked like nothing more than a routine out and a squandered at-bat for the National Leaguers. But Wills saw an opportunity. As the American League rightfielder, Angels star Leon Wagner, glided into foul ground and made the catch, Wills tagged up and raced to the plate, narrowly beating Wagner’s throw in what would be the game’s final run, in a 3–1 National League victory.

Wills won the game’s Most Valuable Player award, taking home with him a large trophy that he made sure the loathsome security guard had a good look at as he exited the stadium. “I still don’t think the guy believed I was who I said I was,” he remembers. He viewed the day as miraculous. But the image of the security guard would haunt him forever, a nagging reminder of too many incidents like it.

Meanwhile, he had become the most confounding weapon in all of baseball. With his batting average hovering around .300, he successfully stole bases on about 90% of his attempts in 1962, despite the best efforts of opposing pitchers, and even a few teams’ cheating grounds crews, to slow him down. During the late stages of the season, it became clear he had an opportunity to break Cobb’s record of 96 stolen bases, set in 1915, or 32 years before a black man ever foot set in the major leagues.

Americans love the chase of an immortal’s record. The pursuit evokes apparitions and gods; it sparks feelings of trespass on the gods’ turf. Just a year earlier, Roger Maris had broken the single-season home run mark of the sport’s Zeus. As Wills dashed toward history, baseball suddenly couldn’t get enough of him or the ghost he was eclipsing. The specter of the late Cobb, baseball’s most famous sociopath and unabashed racist, guaranteed that writers and fans would ceaselessly recount old tales of the bad boy’s depravities and hatreds, heightening the historical drama taking place on the field.

Newspapers counted off his steals as he drew closer to Cobb. Yet, if anything, the numbers overshadowed Wills’s greatest impact: He was changing how baseball was played, and in the process altering how fans watched it. He was, to be sure, a player principally known for one great skill, and so arguably a specialty performer. But so too—in baseball and in life—are other performers specialists—so too is the archetypal home run slugger; so too is the great mezzosoprano. In bringing more attention than ever to base stealing as an art, Wills was doing nothing less than remaking the game’s aesthetics. He was inspiring future Hall of Famers, Lou Brock among them, to stretch the limits of their own great running and stealing skills. Simultaneously, his talent was drawing fans’ attention to how speed could change not only the outcome of a game but its look, infusing it with more thrills and athletic beauty while guaranteeing fewer dreary breaks in the action. His dashes sparked the kind of deafening roars in Dodger Stadium that fans of other teams—with their tepid station-to-station singles, and mammoth home runs followed by pudgy sluggers’ gingerly jogs around the bases—seldom heard.

During late September in St. Louis, with a dash born of inspired improvisation, he moved past Cobb and into history. In Los Angeles, stories about Wills’s feat dominated the news. It was a heady time that would have been even better if the Dodgers had clinched the National League pennant and the opportunity to play in the World Series. But the Dodgers lost 10 of their final 13 games, squandering a comfortable lead in the standings and losing to the Giants in a three-game playoff despite Wills’s 104 steals.

That winter he won the National League’s Most Valuable Player award and received the Hickok Belt as the best athlete of the year in all of American professional sports. Now, he figured, it was time, in his contract discussions with the Dodgers’ iron-fisted general manager, Buzzie Bavasi, that he be rewarded. He wanted a salary considerably higher than the $30,000 he had earned in 1962. But already he was worried over how to ask for it. He had to go into Bavasi’s office alone; no advisers were permitted to accompany a player during salary discussions. He would need to argue by himself for what he deserved, and he hated arguing with Bavasi about anything. He just didn’t know how to do it, sensing there would be trouble if he pushed too hard for anything.

The idol was on top of the world—and already afraid.

*****

The Perfect Game

During my Los Angeles boyhood, on Sept. 9, 1965, I received an invitation from friends: Would I like to go with them to see the Dodgers play the Cubs?

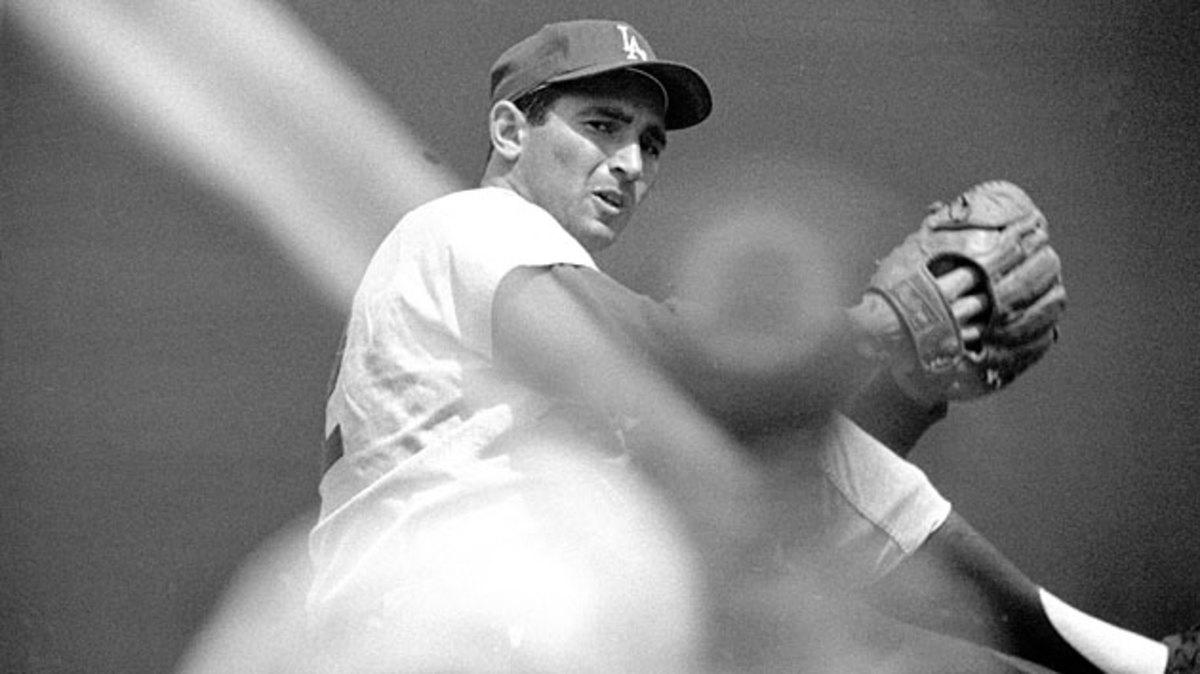

To be in attendance that night at Sandy Koufax’s perfect game has meant, during the 51 years since, to be a part of a small, ever-dwindling group: those spectators still alive who possess memories of the night.

The game marked the apotheosis of Koufax. Even the era’s newspaper sportswriters, a breed typically worshipful of retired giants like Joe DiMaggio but customarily restrained in their assessments of players they had to cover, couldn’t hold back their awe. Koufax, they posited, was no longer merely the best pitcher of his era. In a typical assessment, the Chicago Tribune’s Richard Dozer in his postgame story described Koufax as “the most electrifying pitcher of all time.” The Los Angeles Times’s Frank Finch called him “a Michelangelo.” Off the field, the latest wave of adoration, butting up against Koufax’s need for privacy, would steadily add to his discomfort, leaving him in time to resist questions about the masterpiece, pushing him toward a hermitage of his own making.

The Left Arm of God: Sandy Koufax was more than just a perfect pitcher

The game served as a reminder that nothing on a baseball field is more thrilling than the sight of a power pitcher blowing away All-Star hitters. Three future Hall of Famers—leftfielder Billy Williams, third baseman Ron Santo and first baseman Ernie Banks—occupied the third, fourth, and fifth spots of the Cubs’ lineup. Collectively, they struck out six times that night, in nine failed plate appearances against Koufax. Characteristically, Koufax became stronger as the game progressed, fanning eight of the last 10 Chicago hitters, and the final six, on his way to 14 strikeouts. After the last strike, he had thrown his major league record-breaking fourth no-hitter— one in each of four consecutive seasons.

The signs before the game at Dodger Stadium had been anything but auspicious. It was a bit cool in Chavez Ravine (which often sees temperatures dip at night in September), while Koufax preferred warmth. Young catcher Jeff Torborg, who was getting a start so that the first-string receiver, John Roseboro, could have a night off, noticed as Koufax warmed up that he seemed to have problems getting loose. His fastball didn’t have its usual pop. Some of his curveballs hung in the air like a piñata, ready to be clubbed. But he made it out of the first inning unscathed.

And the opposition was hitless.

By the time Koufax made it through the first inning of any home game without giving up a hit, the dreamers in the crowd had already begun envisioning the possibility of a no-hitter. After all, this was the reason why many of them had bought tickets. It was part of why my hosts had wanted to be here. We sat on the third-base side in Aisle 27, Row S (one of my friends, 14-year-old Marti Allen, had the good sense to keep her ticket stub), of Dodger Stadium’s fourth deck, the so-called reserve level.

With two outs in the top of the second inning, a rookie in his first major league game, lefthanded-hitting outfielder Byron Browne, stepped into the batter’s box and smacked a line drive. Koufax had thrown a high hanger that sat up in the strike zone, and Browne ripped it toward centerfield.

To this day, I can see the ball moving on a low line. I can see the tall, lefthanded centerfielder Willie Davis, in whose direction the ball was speeding. Aisle 27, Row S, afforded a perfect view. When it left Browne’s bat, the ball had the appearance of being a certain base hit, a rather routine single to center field that would drop in front of Davis. But luck intervened. Browne had hit the ball so hard that it hung in the air. It was a rope, as ballplayers commonly call such a shot, a tribute to the quality of contact made and to its beautiful look, a ghostly white blur that stays at the same height for a considerable distance, as straight as a taut rope.

Some people mistakenly thought that Davis hadn’t needed to move an inch. In truth, with a few long strides, the fleet Davis came in and closed on an unpredictable ball that would have posed a very stiff challenge for slower outfielders, who would have had difficulty reaching it before it began sinking. Davis reached the liner while it was still a rope. He caught it on his glove side, about thigh high. He made the tough play look so easy, so ordinary, that he would never receive his just due in newspaper accounts or histories.

• Subscribe to get the best of Sports Illustrated delivered right to your inbox

By the third inning, a finally limber Koufax had found his best fastball and curve. Thereafter, the strikeouts mounted. Los Angeles scored the game’s only run when Cubs catcher Chris Krug committed a throwing error on a Dodger steal.

Krug felt awful. He thought he had let down his pitcher, 26-year-old journeyman Bob Hendley, who would give up only one hit the entire night.

Krug had an opportunity to atone for his mistake in the ninth inning, as the first Chicago hitter facing Koufax.

With the count two-and-two, Krug saw the fastball well as it left Koufax’s hand. He liked everything about it. He especially liked its location, which was right in line with the bottom of his knees and a bit on the inside part of the plate, in his power zone.

Fifty years later, he would still be able to see it. Every time he begins swinging at it, he thinks, I’m right on it.

“I remember what I was thinking as it was coming. I’m thinking, ‘I’m gonna hit the snot out of this thing.’

“I swung right through it. I still can’t believe I missed it.”

After pinch-hitter Joe Amalfitano struck out, the Cubs’ last threat was 34-year-old Harvey Kuenn. A former American League Rookie of the Year and a 10-time All-Star who, in 1959, had led the AL in hitting with a .353 average, Kuenn had become an aging role player. “See you soon,” he said to Amalfitano, as the latter man headed back to the dugout.

But Torborg knew Kuenn was a battler. “He wasn’t afraid,” Torborg said. Torborg reminded himself of a fundamental: Hold on to the ball.

Koufax’s final pitch was a 2–2 fastball.

“Swung on and missed—a perfect game,” yelled Dodgers announcer Vin Scully, who then stopped talking for nearly 40 seconds, letting the roar fill his broadcast.

Unable to forget his unfortunate throw, Krug suffered afterward. “One bad throw did all that to me…,” he remembered, in 2014. “It stuck with me; it was kind of a struggle.”

Late in 1965, Krug mentioned it in passing to Torborg. During that winter, he found himself at a Palm Springs charity golf tournament when Koufax walked up to him. “I guess Torborg said something, because Sandy was kind of concerned,” recounted Krug, who was moved that Koufax would make time to talk to someone he really didn’t know. “Sandy just told me, ‘It wasn’t your fault—it was a tough play.’ He wanted to make sure I understood that. I just basically said, “Thanks—I appreciate it.’ But you never forget something like that. You think to yourself, So that’s Koufax.”

After their retirements, Torborg began making a point of calling Koufax—whom he frequently calls by his formal first name, “Sanford,” in private—nearly every year on the anniversary of the perfect game. But they don’t talk much about the game itself. Even around the elites he encounters on those rare occasions when he consents to being honored somewhere, Koufax resists being lured into a discussion of his no-hitters. The impression left is that of a man weary of being caged in the 1960s.

I have some sense of what such exchanges are like. In 2009 Koufax called me, in response to my request for an interview about Wills, who was the subject of a newspaper story I was writing at the time. At the start of our discussion, he clarified a point: He wanted to answer only those questions related to Wills, whom Koufax wished to see elected to the Hall of Fame.

At some point, I mentioned that I’d attended the perfect game as a kid.

There was an uncomfortable pause. He didn’t voice irritation over my rather transparent attempt to get him to talk about a subject that was supposed to be off the table. He didn’t sigh or cluck his tongue or do any of the things that annoyed subjects sometimes do. In fact, he didn’t speak at all. There was complete silence on the other end of the phone for several uneasy seconds, until I got the point and changed the subject. Then, as if nothing unusual had just happened, he answered more questions about Wills, thus supremely tactful in rebuffing me and moving on. Nonetheless, the moment served as a reminder that for the time being at least he’d closed the book on any lengthy interview about the perfect game or his life, closed it as certainly as J. D. Salinger had closed himself off from talking about The Catcher in theRye or anything else.

And that should be no surprise. We ought to allow the men we turn into deities to have their sanctuaries.