Ghostbusters: Cubs have everything it takes to finally win World Series

This story appeared in the Oct. 10, 2010 issue of SPORTS ILLUSTRATED. Subscribe to the magazine by clicking here.

The Chicago Cubs know how to party. They won 57 times this year at Wrigley Field, the most in the 101 seasons the franchise has played in the heirloom of a ballpark at the corner of Addison and Clark. After each of those victories, just before entering their newly renovated 30,000-square-foot clubhouse proper, which includes a sensory-deprivation tank and a yoga studio, they repaired to a dedicated celebration room. Amid strobe lights, a smoke machine and pulsating dance music, the Cubs would spend 10 minutes reveling in victory.

After a seasonlong party, Chicago enters the playoffs as the strongest favorite since the legendary 1998 Yankees. Three of the nine other playoff entrants may have a chance to knock off the Cubs, but based on regular-season results, one team in particular has almost no shot of beating them: the Cubs themselves.

It’s not just that Chicago’s pitchers allowed the fewest runs in the majors and that its hitters scored more runs than every team except Boston and Colorado. The Cubs also boast the stingiest defensive unit in a quarter of a century. Under a think tank of no fewer than nine coaches, including a “Run Prevention Coordinator,” and implemented by some of the most athletic defenders in baseball, the Cubs essentially have opened a traveling exhibit of the Art Institute of Chicago. Their defense is that exquisite. Call it a Cub-ist aesthetic.

“I don’t know the last time we beat ourselves,” president Theo Epstein says. “Maybe once every two weeks you can count on giving an opponent four outs in an inning, which forces your pitcher to throw extra pitches and then you have to go to your bullpen a little earlier than you want. This year it seems like that happened three or four times the whole year.”

The Cubs have three Cy Young Award candidates (righthanded starters Jake Arrieta and Kyle Hendricks and lefty Jon Lester) and two Most Valuable Player Award front-runners (third baseman Kris Bryant and first baseman Anthony Rizzo), but defense is the secret sauce to their pursuit of the franchise's first World Series title since 1908. The only task at Wrigley Field this month more difficult than finding tickets may be for a visiting player to find hits.

Start with this: The Cubs allowed the fewest balls in play (3,740) in any full season since the live ball era began in 1920. Batters hit only .257 when they did put balls in play, the lowest such average against a club in a full season since the ’76 Yankees. Chicago’s defenders turned 72.8% of those balls in play into outs, the best defensive efficiency rate since the ’91 White Sox.

How the Cubs were built: Turning baseball's longest-running losers into winners

Defense is even more important in the postseason, when games are usually lower scoring. Starting in 2012, when the playoffs expanded to include two wild-card berths in each league, runs declined from 8.40 per game in the regular season to 7.55 in the postseason, a 10.1% drop.

Postseasons have been fickle for favorites since 1995, when the wild card was introduced. Only four of 26 teams (including ties) with the best record entering the playoffs in that time have won the World Series: the 1998 and 2009 Yankees and the 2007 and ’13 Red Sox. But Chicago is not your ordinary “best record” team. The Cubs are only the eighth team in the past 40 years to win at least eight more games than the next best club. Four of the previous eight teams so far ahead of the field won the World Series.

Chicago enters the postseason healthy and with no obvious flaws. The question, 108 years since their last championship, no longer is whether the Cubs can win the World Series. The question is, how can they not win it? Bad bounces, hot pitchers, fluke plays—each can cause a favorite to fall in October. The Cubs, though, have thrown plenty of brainpower and talent at making sure they won’t lose because of their defense.

*****

The Cubs’ defensive paradigm began with a hitting coach. In October 2014, Epstein hired Astros hitting coach John Mallee, who grew up a Cubs fan as the son of a Chicago police officer.Mallee mentioned how in Houston he benefited from having somebody who could coordinate all things hitting, including scouting reports and video. Epstein liked the idea. He quickly decided to dedicate two “coordinators,” one to oversee the offensive side of the game and one for the defensive side. For the former, Epstein named video coordinator Nate Halm, then 29 and a former college catcher at Seton Hall and Miami (Fla.), to the position of Coordinator, Advance Scouting. Unoficially, Halm became the Run Production Coordinator.

For the second coordinator position—unofficially, the Run Prevention Coordinator—Epstein hired Tommy Hottovy, then 33, in December 2014. Hottovy pitched in 17 major league games in 10 professional seasons before blowing out his shoulder in Cubs spring training camp in ’14. While rehabbing his shoulder that summer, Hottovy, who graduated from Wichita State in ’04 with a degree in business administration and a minor in economics, took a Sabermetrics 101 online course from Boston University.

Hottovy is the bridge between the back-office analytical wonks and the on-field staff. He analyzes the vast amounts of numerical and video data as well as charting his own observations.

The Cubs’ game plans for pitching and defense begin with pitching coach Chris Bosio. He, Hottovy and catching instructor Mike Borzello coordinate the strategy—how to attack hitters and where to best position the seven players behind the pitcher. Bullpen coach Lester Strode conveys the plan to the relievers.

First base coach Brandon Hyde and bench coach Dave Martinez make in-game positioning adjustments. And third base coach Gary Jones is the infield instructor who has taken the rough edges off Bryant’s game at the hot corner. Though 6' 5", Bryant is best at playing lower, which has improved his reaction to slow rollers and grass-skimmers, and he has rid himself of a habit of patting the ball in his glove once or twice before throwing.

“This is a nice example of what happens when you marry pitching and defense,” Epstein says. “It’s a beautiful thing when it works together. It’s hard to quantify some of it, like the confidence it breeds in a pitcher. When you’re confident that balls in play are going to be outs, it’s easier to game-plan.”

Ranking all possible World Series matchups, from Red Sox-Dodgers to Rangers-Giants

Manager Joe Maddon likes to say that the team’s motto for positioning fielders is, “We catch line drives.” The system is designed to defend the likely areas of hard-hit balls. In an age when shifts are all the rage—and Maddon was one of the earliest adopters of the strategy as Angels bench coach in the late 1990s—the Cubs are among the teams that shift the least. Epstein, however, scoffed at the notion that Chicago does not shift much.

“We’re last in the league in shifts because of the way they define it,” Epstein says. The standard definition is when the “off” middle infielder—the shortstop when a lefthanded batter is at the plate; the second baseman when a righthanded batter is up—is positioned on the other side of second base. “Believe me, we position for every pitch,” Epstein says. “We just don’t meet the criteria of ‘shift.’ We do it through scouting reports and numbers and based on our own observations.”

The Cubs, however, do differ from most clubs in positioning their fielders. Most teams begin with spray charts—monitoring where a hitter most often hits the ball. While Chicago uses spray charts, it prefers to put more confidence in its pitchers and the kind of contact they elicit. The question the Cubs like to ask: Where is the optimum position for each fielder for this pitcher to secure an out?

After such planning, skill takes over, and the Cubs are loaded with it. Last winter Epstein raised eyebrows in the industry by giving $184 million over eight years to free agent Jason Heyward, the richest investment ever for an outfielder who had never driven in or scored 100 runs. They paid that steep price in part because of his superior defense in rightfield. Heyward has been a bust at the plate, hitting .230 with just seven home runs, but his defense has been spectacular.

“His attention to detail is impressive,” Epstein says. “He’s extremely prepared and knows exactly what we’re trying to do. He knows the game situation, he reads swings, he anticipates where the ball will be hit.

“He’s so smart, it’s almost like he’s going through a computer in his head. And he throws with pinpoint accuracy.”

When Heyward is joined by superutility player Javier Baez, the Cubs have two of the best defenders in baseball on the field. Baez is a natural shortstop who has played all four infield positions—mostly third base and second base—as well as leftfield. Maddon calls Baez “the best tagger I’ve ever seen.”

Epstein goes even further, saying Baez’s skills at tagging runners “are as good as any player at any aspect in the game. Javy Baez is to tagging what Giancarlo Stanton is to raw power. He’s worth a couple of wins a year.”

Epstein explains that in the era of instant replay, the biggest variable in the outcome of a stolen base attempt at second base—with all other variables being equal (an average runner, a pitcher with average time to the plate, an average throw from the catcher)—is the tagging prowess of the middle infielder. Baez’s ability “to know where the runner’s hand and foot are in space without looking, then almost instantaneously catch the ball, control it and tag is amazing,” says Epstein.

Rizzo is an elite first baseman. Shortstop Addison Russell, though he lacks outstanding arm strength, is light and quick on his feet. And centerfielder Dexter Fowler is having his best defensive season since his rookie year of 2008, according to Fangraphs’ defensive runs saved.

So good are the Cubs at pitching and defense that in their 103 wins, they allowed a total of 15 unearned runs. Veteran pitchers Arrieta (.242), Hendricks (.252), Lester (.258) and John Lackey (.259) all have allowed the lowest batting averages on balls in play in their careers, and they will all enter the postseason rested and healthy. So what’s an opponent to do?

*****

Wrigley Field's Most Memorable Moments

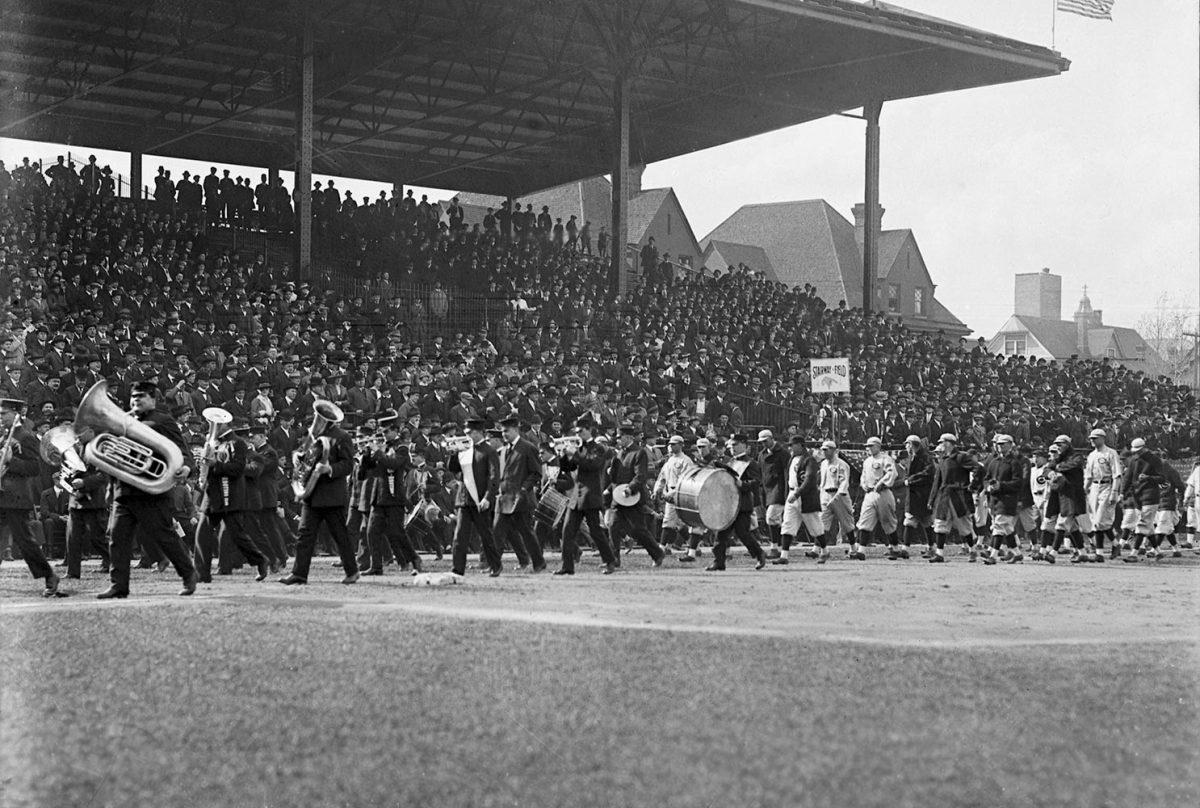

April 20, 1916: First Cubs game

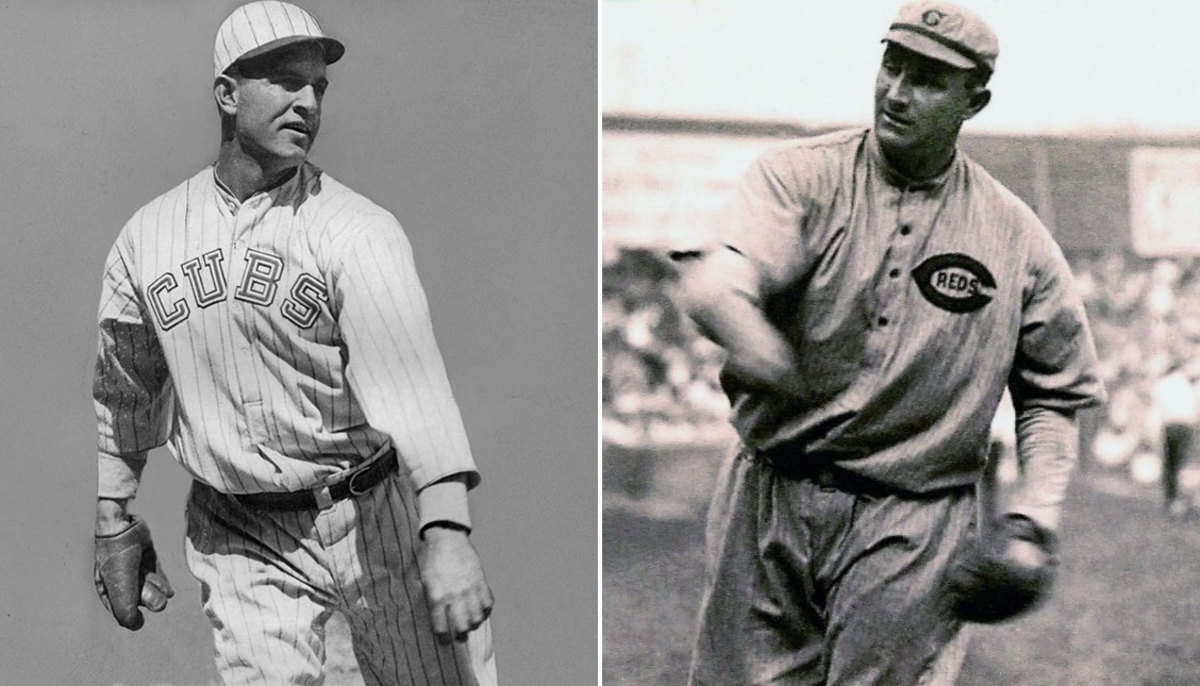

May 2, 1917: The Double No-hitter between Jim “Hippo” Vaughn and Fred Toney

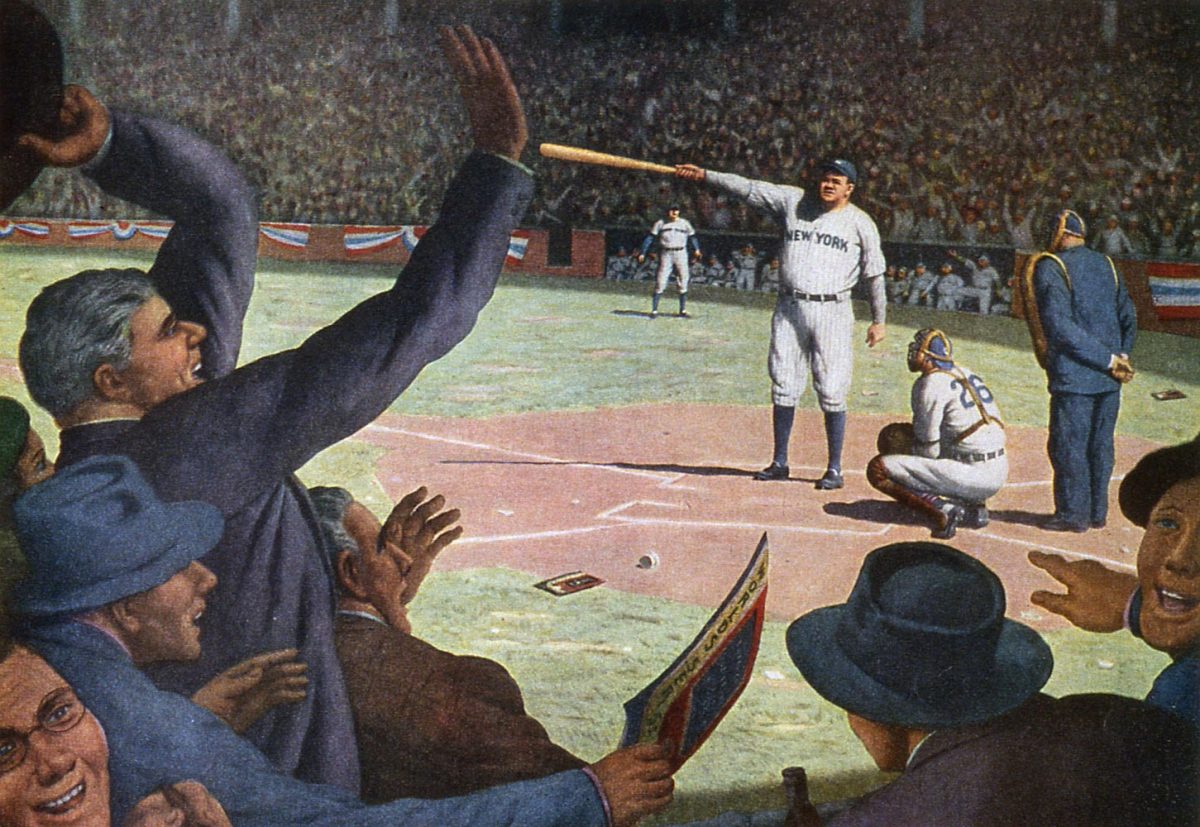

Oct. 1, 1932: Babe Ruth’s Called Shot

1937: Ivy appears

Sept. 28, 1938: Gabby Hartnett’s Homer in the Gloamin’

Oct. 6, 1945: Curse of the Billy Goat

Pictured: Ernie Banks with Sam Sianis, owner of The Billy Goat Tavern, in 1994.

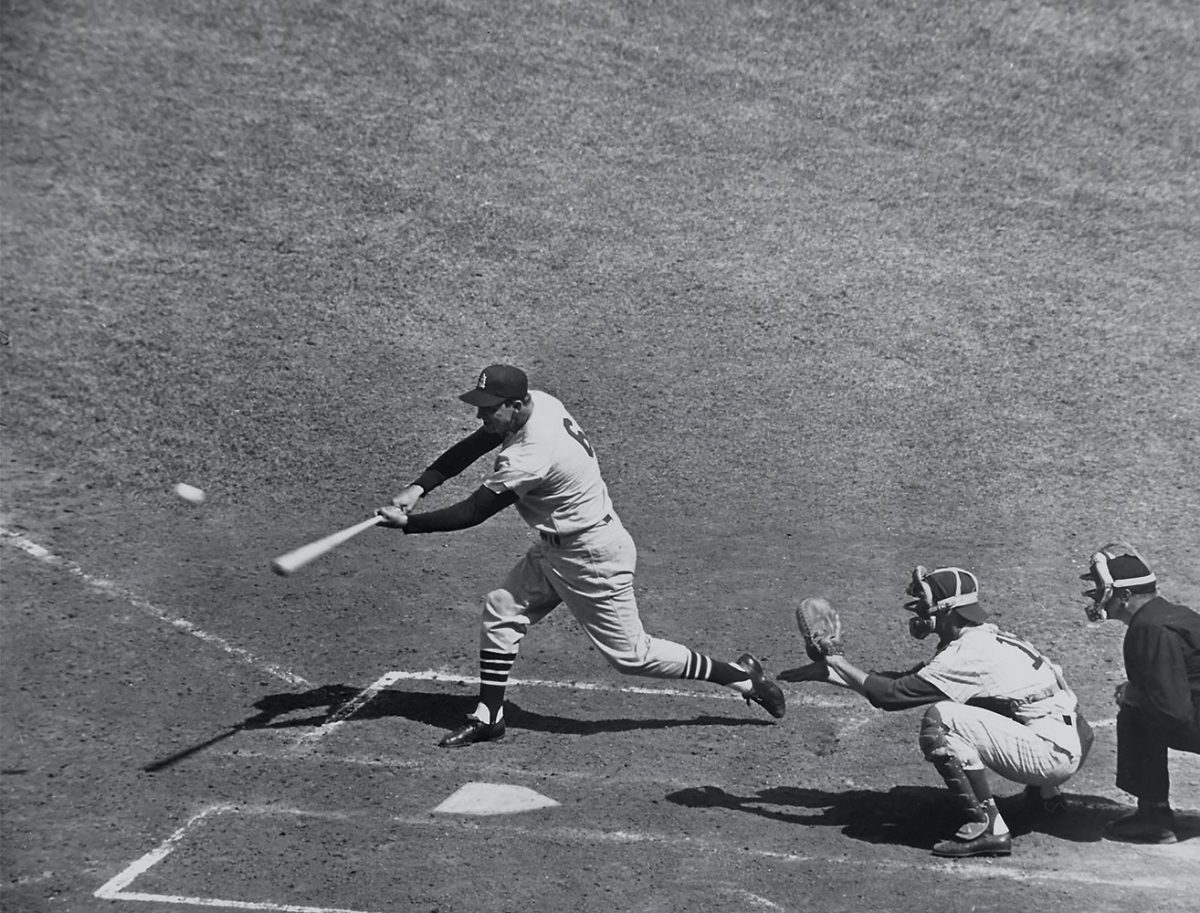

May 13, 1958: Stan Musial gets his 3,000th career hit

Dec. 29, 1963: Bears beat Giants 14-10 in the NFL Championship game

Dec. 12, 1965: Gale Sayers scores six touchdowns

May 12, 1970: Ernie Banks hits his 500th home run

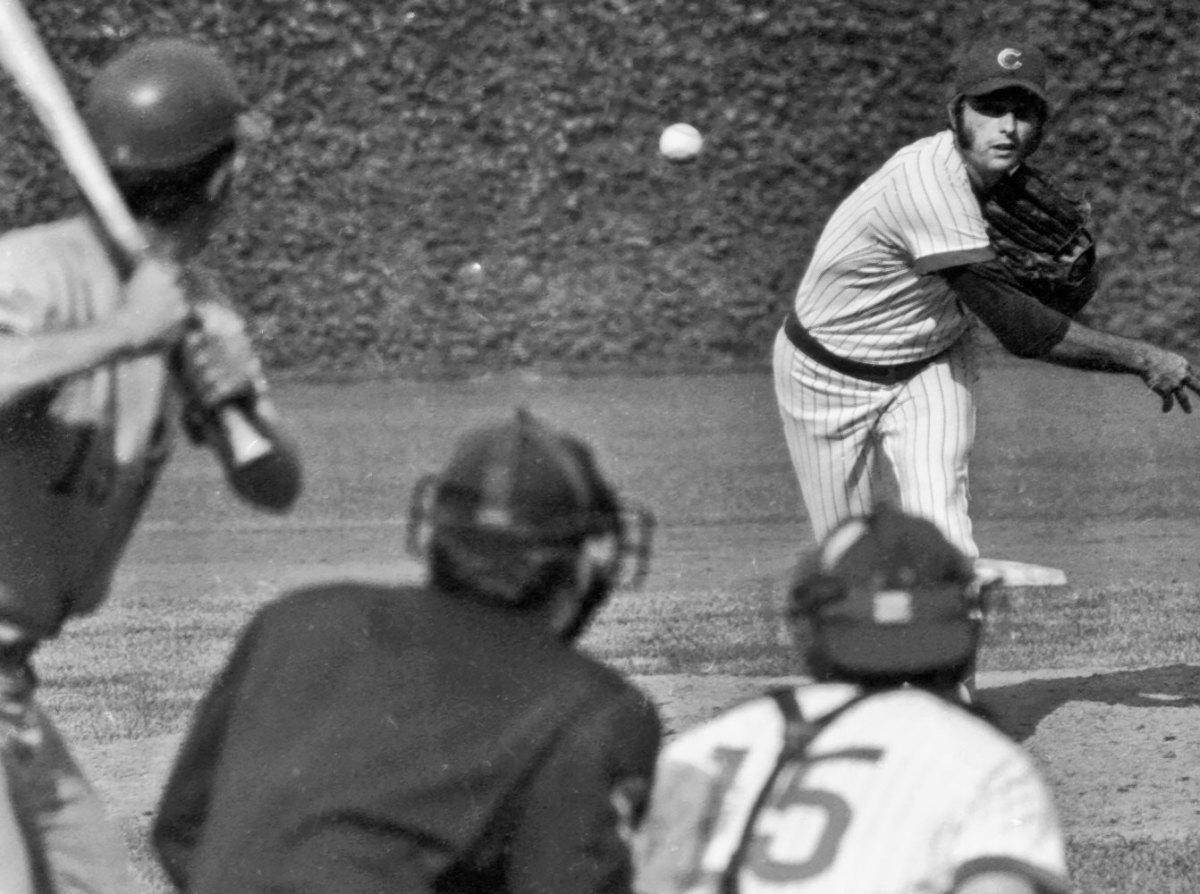

Sept, 2, 1972: Milt Pappas' near-perfect game, missed by one pitch on a controversial ball four

April 17, 1976: Mike Schmidt's four homers in the Phillies comeback, down 13-2, to win 18-16

May 17, 1979: 45 total runs scored in the Phillies 23-22 win over the Cubs

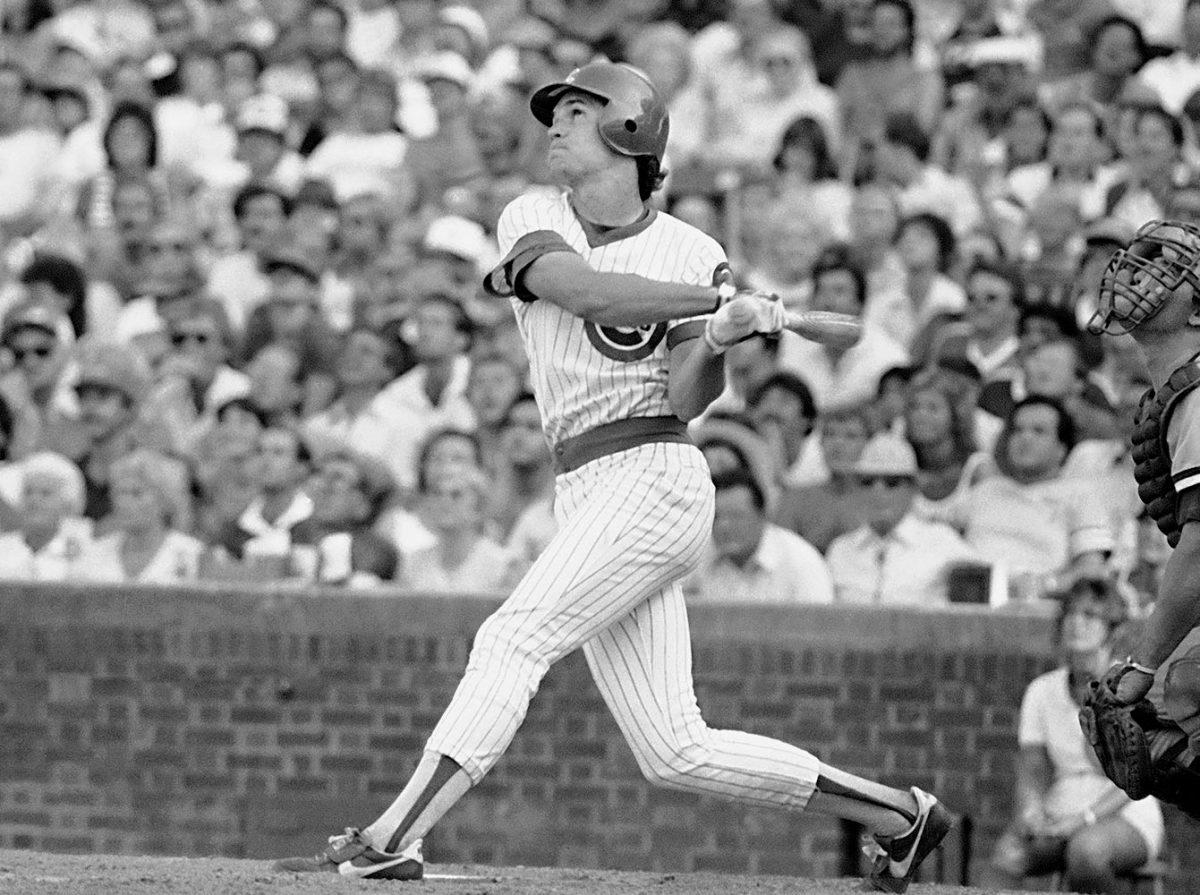

June 23, 1984: The Sandberg Game — hits two home runs and seven RBIs in the Cubs 12-11 win over the Cardinals

Aug. 8, 1988: First night game

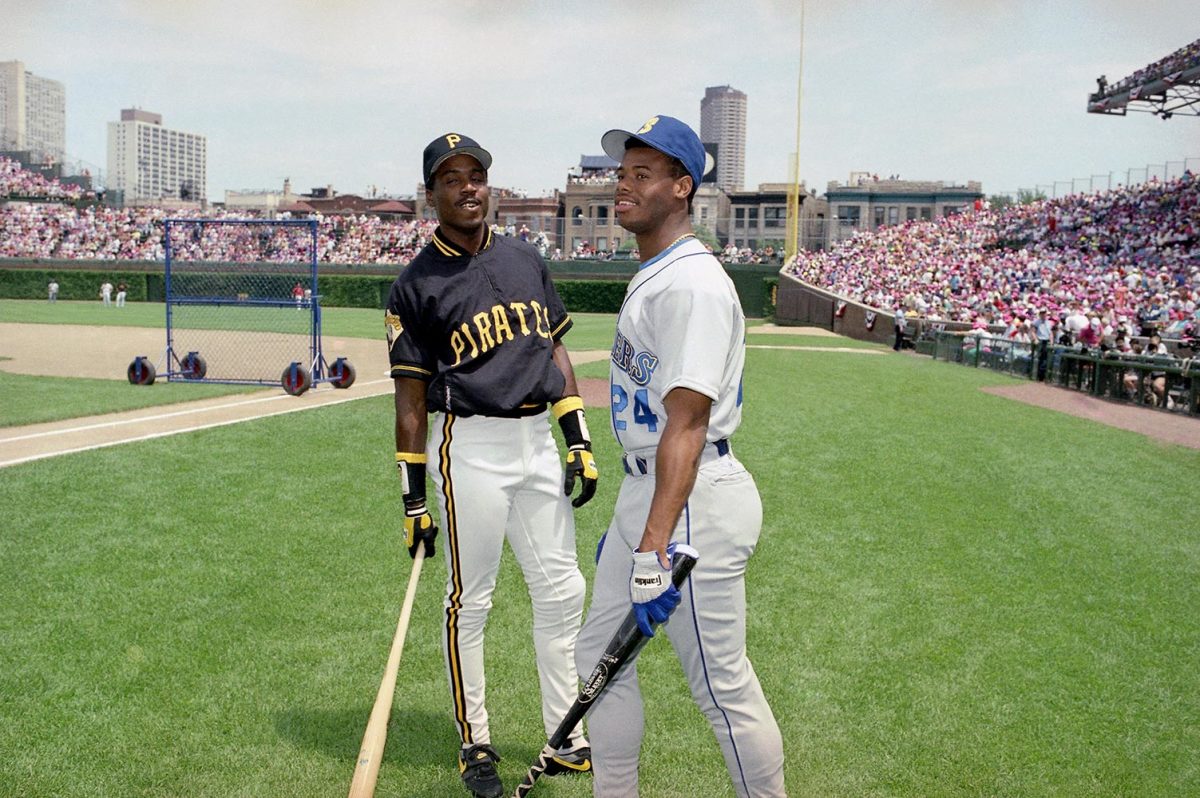

July 10, 1990: Cubs host most recent All-Star Game

April 13, 1994: Michael Jordan plays for White Sox in Windy City Classic

May 6, 1998: Rookie Kerry Wood strikes out 20 Astros

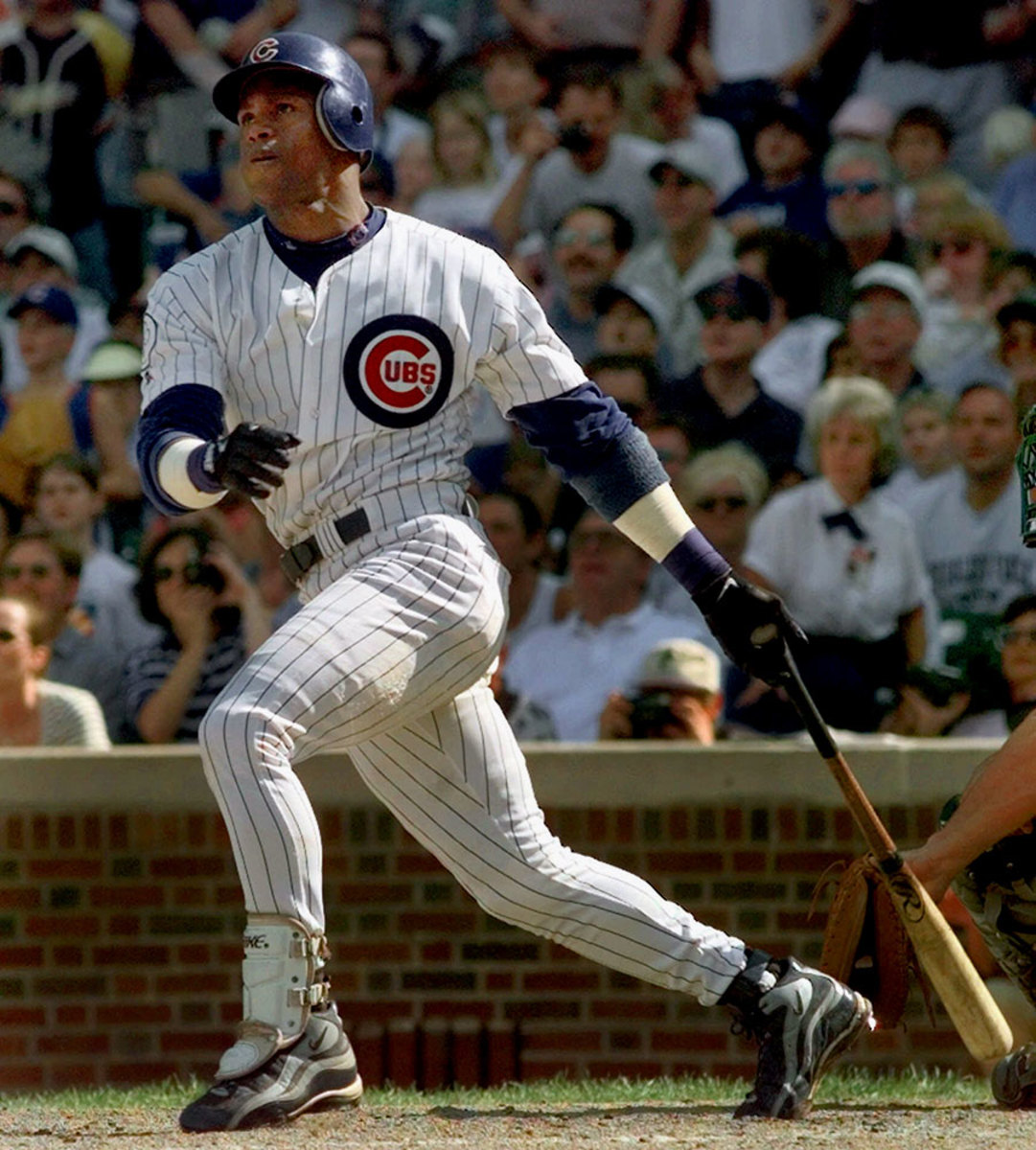

Sept. 13, 1998: Sammy Sosa hits 61st and 62nd home runs

Oct. 14, 2003: The Bartman game

Aug. 5, 2007: Mets’ Tom Glavine wins his 300th game

Jan. 1, 2009: Red Wings beat Blackhawks 6-4 in Winter Classic

Nov. 20, 2010: Using only one end zone for offense, Illinois beats Northwestern 48-27

If anything can stop the Cubs, maybe it’s the dulling of an edge after having clinched their division back on Sept. 15—22 days before Friday’s Game 1 of the Division Series against the winner of Wednesday’s wild-card game between the Giants and the Mets.

“Look at both times this year we had to clear our focus and reset,” Epstein says. “In the last week of spring training we ramped up for Opening Day and started 25–6. Then the All-Star break. We struggled a bit in the last couple of weeks of the first half. Then after the reset we went 24–8. So this is our third and final restart. It’s about everybody taking the same approach.”

What could go wrong? Last year the Mets took out Chicago in the NLCS on the strength of their powerful starting pitching. But the 2016 Cubs are a more versatile offensive team than the ’15 version. They are a better situational hitting team (they scored a runner from third with less than two outs 49.7% of the time this year, up from an MLB-worst 40.5% in ’15), a better fastball hitting team (.213 vs. power pitchers in ’15 compared with .229 this year), and they don’t strike out as much (1,518 K’s in ’15, the most in the majors, but 1,339 this year), thanks to the addition of free-agent second baseman Ben Zobrist and the growth of Bryant and Russell, who both improved their contact percentage. Moreover, while Lester and Arrieta ground through last September, this year they enjoyed more rest and shorter outings down the stretch because of the team’s huge lead in the NL Central standings, which was at least double figures starting Aug. 7.

One Chicago vulnerability is to stolen bases because none of its starting pitchers are expert at holding runners. The offense has some holes, especially if Maddon puts a premium on defense and uses Heyward, who struggles against velocity, and Baez, who can’t hit breaking balls away, in the same lineup. Those holes in their swings can be exploited by the better pitching of the postseason. Teams can pitch around the Cubs’ MVP candidates in the heart of the order to put pressure on Heyward with runners on base.

Go Cubs Go: How Chicago's victory anthem keeps a father alive for his daughters

Heyward’s lefthanded bat is particularly important because Chicago has a predominantly righthanded lineup. Its righthanded hitters strike out in 25.6% of its plate appearances against righthanded pitching. (The league average is 21.8%.) The best kind of righthanded pitchers to trot out against the Cubs are those with premium sliders that work down and away from righties Baez, Bryant, Russell, Willson Contreras and Jorge Soler, all of whom are prone to chasing such a pitch.

In that regard the Nationals, who play the Dodgers in the Division Series, may present the most formidable matchup for Chicago. Both Max Scherzer (fifth) and Tanner Roark (22nd) are among the top 25 righthanded starters in slider value, according to Fangraphs. Washington, however, does not enjoy the prime health the Cubs do. Pitcher Stephen Strasburg is out for at least the Division Series with elbow inflammation, catcher Wilson Ramos is out for the season with a torn ACL and second baseman Daniel Murphy (glute) and rightfielder Bryce Harper (thumb) were nursing nagging injuries last week.

The Dodgers could present their own matchup problem for Chicago with pitcher Kenta Maeda (fourth in righthanded slider value), not to mention a healthy Clayton Kershaw and the deepest, best bullpen in baseball. Rookie manager Dave Roberts made more pitching changes this season than any manager in history and would deploy his relievers the way Chicago politicians were once said to deploy voters to cast ballots: early and often. Roberts’s bullpen is loaded with righthanded power sliders, especially from the rejuvenated Joe Blanton.

By any means, taking down the Goliath that is Chicago will be an achievement earned, not given. Opponents have to assume the Cubs will play a clean game, with no mistakes, and must match their defense and exceed their pitching. The lessons from postseasons past suggest the way to cut down a team like Chicago is to win low-scoring games.

Like the Cubs, the 1990 Athletics led the majors in ERA and in defensive efficiency en route to winning 103 games. Oakland, though, was swept in the World Series by a 91-win Reds team. Cincinnati allowed the A’s only eight runs over four games, including just one in 241⁄3 innings thrown by righthanded power pitchers.

The 1969 Orioles were another massive favorite. They won 109 games while leading the majors in ERA (2.83), batting average on balls in play (.246, still the best since the mound was lowered that year) and defensive efficiency (.743). The 100-win Mets, after losing Game 1, pulled off a miracle by beating Baltimore in four straight games, 2–1, 5–0, 2–1 and 5–3. In those four wins New York’s righthanded pitchers allowed the Orioles one run over 191⁄3 innings.

The best precedent for the Cubs is the ’98 Yankees, a team that entered that postseason far better than any other club (their 114 wins were eight clear of the field) and excelled at the three major phases of baseball: hitting (first in the majors in runs), pitching (first in the AL in runs allowed) and defense (first in the majors in defensive efficiency). They were just as dominant in October: They went 11-2, outscored opponents 62-34, posted a 2.42 ERA and gave up only two unearned runs.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, in 1908, not only did Wrigley Field not exist but also neither did traffic lights, the 19th Amendment or World Wars. Chicago held Detroit to a .209 average in that series and made just two errors in five games. So much of the world has changed since then, but not the importance of pitching and defense, still the best ways to get a party started.