With Rizzo raking and Lester on tap in NLCS Game 5, Cubs are having fun again

LOS ANGELES—The Dodgers had the Cubs right where they wanted them Wednesday: down two games to one in the National League Championship Series and, based on 18 consecutive scoreless turns at bat, witness to the construction of a national narrative that the Team of the Century was about to spiral down the drain of irrelevance. The Cubs looked tight, and the whiteboard inside the Dodgers’ clubhouse seemed to confirm the diagnosis. In red marker, a Dodger wrote, “If We Keep Having Fun, They Won’t.”

In the last hours of golden Southern California daylight Wednesday, as the Cubs practiced their batting and their insouciance in the face of their own twilight, Chicago general manager Jed Hoyer was asked where the offense might come from on this dormant team.

“I think it starts with [Dexter] Fowler, because he’s our leadoff guy,” Hoyer said. “But Anthony Rizzo is big. He’s a home-run hitter and he means so much to us. You need your stars to play well.”

By the end of a long night that saw the Cubs win, 10–2, Chicago had plastered 13 hits around Dodger Stadium, and the Dodgers had played so poorly that their final line score on the mid-Century scoreboard was the same as the area code of a small Caribbean nation: Aguilla, to be exact (reppin’ the 2-6-4).

Fowler did contribute two of the Cubs’ hits, but no hit was bigger than the home run Hoyer’s big guy provided: a blast by Rizzo off Pedro Baez in the fifth that had the effect of a defibrillator. It restored the Cubs’ heartbeat to its normal rhythm. It was just one run that pushed the Chicago lead to 5–0, but it meant that Rizzo was back, a truth he verified with a two-run single to right in the sixth and a single to left in the eighth. Until those three hits, Rizzo had been 2-for-28 in the postseason, stranding an entire Chicago voting precinct on the bases.

“That was big for Rizz," catcher David Ross said. "He was putting a ton of pressure on himself.”

It was a most productive night for Chicago. Today the Cubs are tied in the series; they have the Game 5 pitching matchup in their favor (their ace, Jon Lester, goes against Kenta Maeda); they have the home field advantage for what is now a best-of-three series and their bats have returned. The Windy City is exactly that today because of an enormous collective exhale.

Don’t also discount another edge Game 4 provided the Cubs: They have Rizzo back. Rizzo is a grinder who rarely misses a game (just nine over the past two years) and has been incredibly consistent the past two years when it comes to runs (94 in 2015, 94 in '16), homers (31, 32), RBIs (101, 109), total bases (300, 317) and adjusted OPS (146, 146).

• Cub Hub: Check out all of SI's content as Chicago chases history

There’s more, however, to what makes Rizzo so important. The man is the fulcrum of the team, the organizer of team parties and dinners, a well-mannered gentleman and a cancer survivor who knows all about proper perspective when it comes to the stock market ride that is postseason baseball. The national television audience gained a window into Rizzo’s emotional ballast to the team when microphones captured a sweet chat between Rizzo and home plate umpire Angel Hernandez during Game 4.

Rizzo apologized to Hernandez for assuming a ball four call on his at-bat against Baez—he dropped his bat and began jogging to first—only to have Hernandez call it a strike. “No worries,” Hernandez said to him, and then complimented Rizzo on his deportment. In the heat of battle, the sportsmanship sold baseball better than any slick advertisement.

Zobrist’s bunt sparks Cubs offense as Rizzo returns to form in NLCS Game 4

The bad news for Los Angeles is that Chicago's lineup becomes much tougher to pitch to if Rizzo is raking. Both the Giants in the NLDS and the Dodgers in the NLCS had flustered Rizzo by not attacking him. Both teams liberally threw him off-speed pitches, especially curveballs, and especially in hitter’s counts. Rizzo, giving in to the want of October, often chased the pitches.

Rizzo was going so bad that in his final at-bat of Game 3, against the hard cutter of Dodgers closer Kenley Jansen, teammate Matt Szczur (pronounced SEE-zur) told him, “Why don’t you use my bat?” It’s a running joke between the two of them. Both use Marucci bats of approximately the same size, but in different models.

“Every time he uses my bat,” Szczur said, “he gets a hit. I’m not kidding.”

So Rizzo took Szczur’s bat to the plate. He didn’t come back with it. Jansen exploded the bat in several pieces with his cutter, a barrage of kindling falling so numerously and dangerously from the sky that Jansen rose his arms to cover himself rather than chase the weak grounder that resulted from Rizzo’s contact. The ball rolled harmlessly, like a 90-foot putt on a slow green, allowing Rizzo to reach base with a hit.

Chicago Cubs All-Time Team

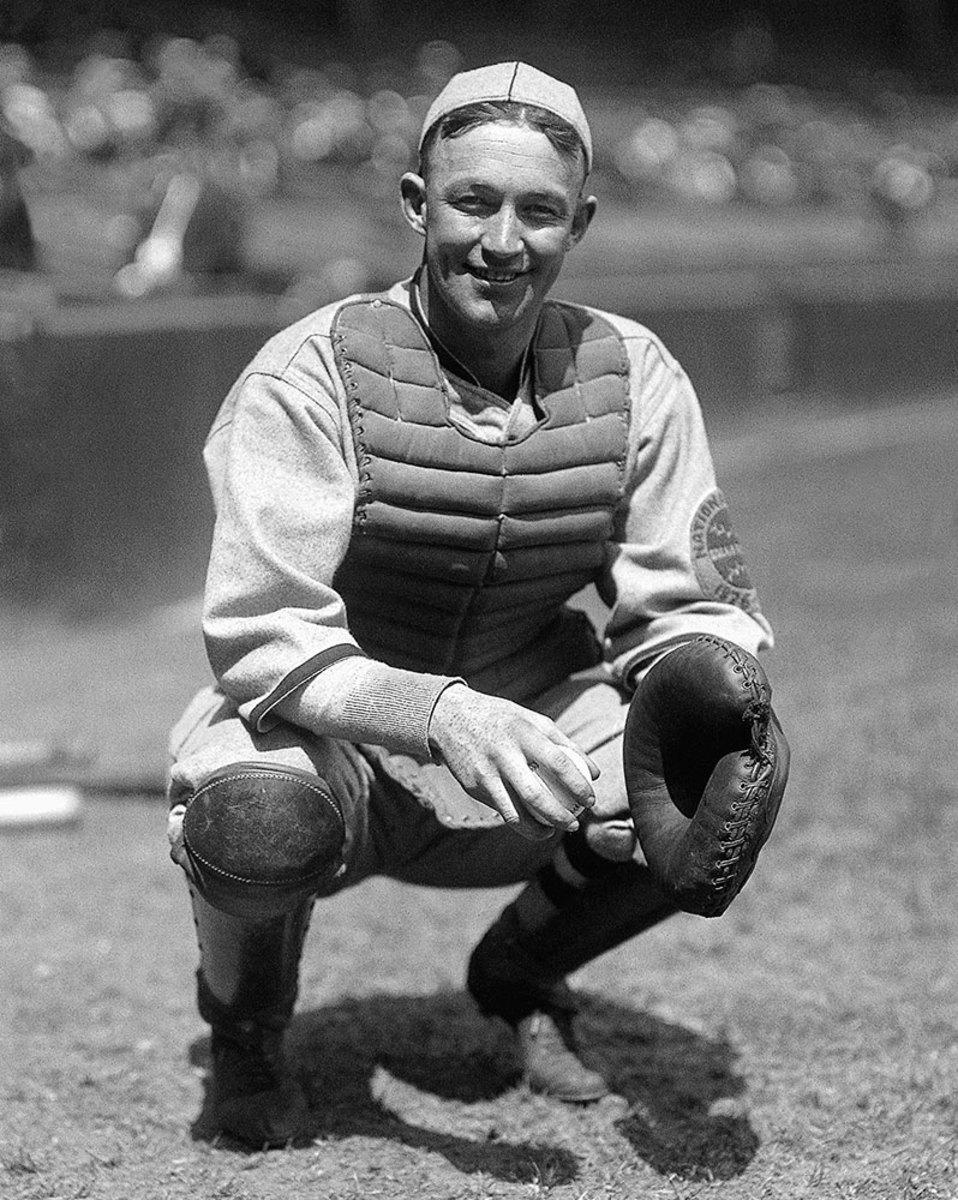

Catcher: Gabby Hartnett

Until Mr. Cub came along, that was a moniker that would have suited Hartnett just fine. He’s still the franchise’s career leader among catchers in games played, at-bats, runs, hits, doubles, triples, home runs, RBIs, batting average, on-base percentage and slugging percentage. Hartnett was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1955.

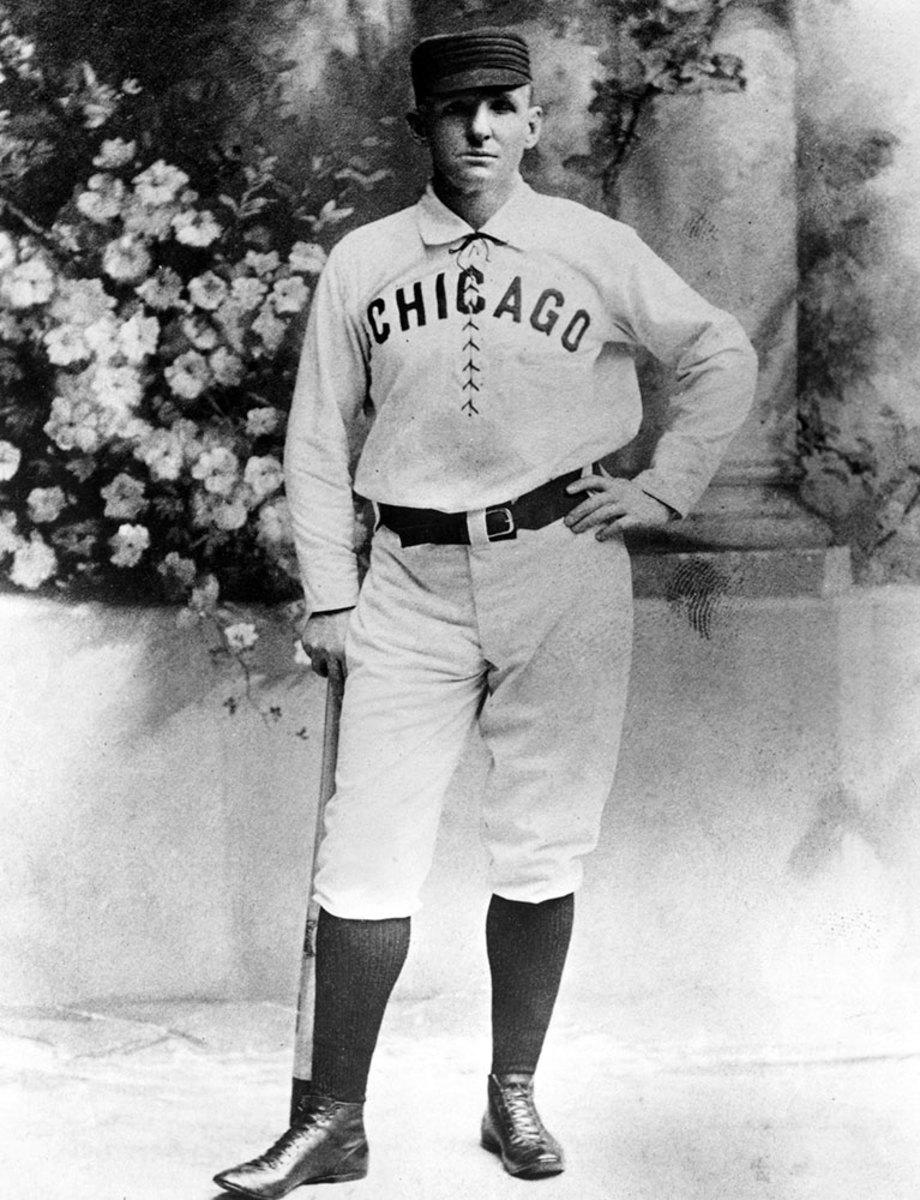

First Baseman: Cap Anson

This may have been the most competitive position, and that’s without including Banks, who actually played more games at first base than he did at shortstop. Bill Buckner, Mark Grace and Derrek Lee from more recent decades are all intriguing candidates, but the choice is Anson, a Hall of Famer and 19th-century stalwart whose franchise marks for runs, hits, doubles, RBIs and batting average still stand.

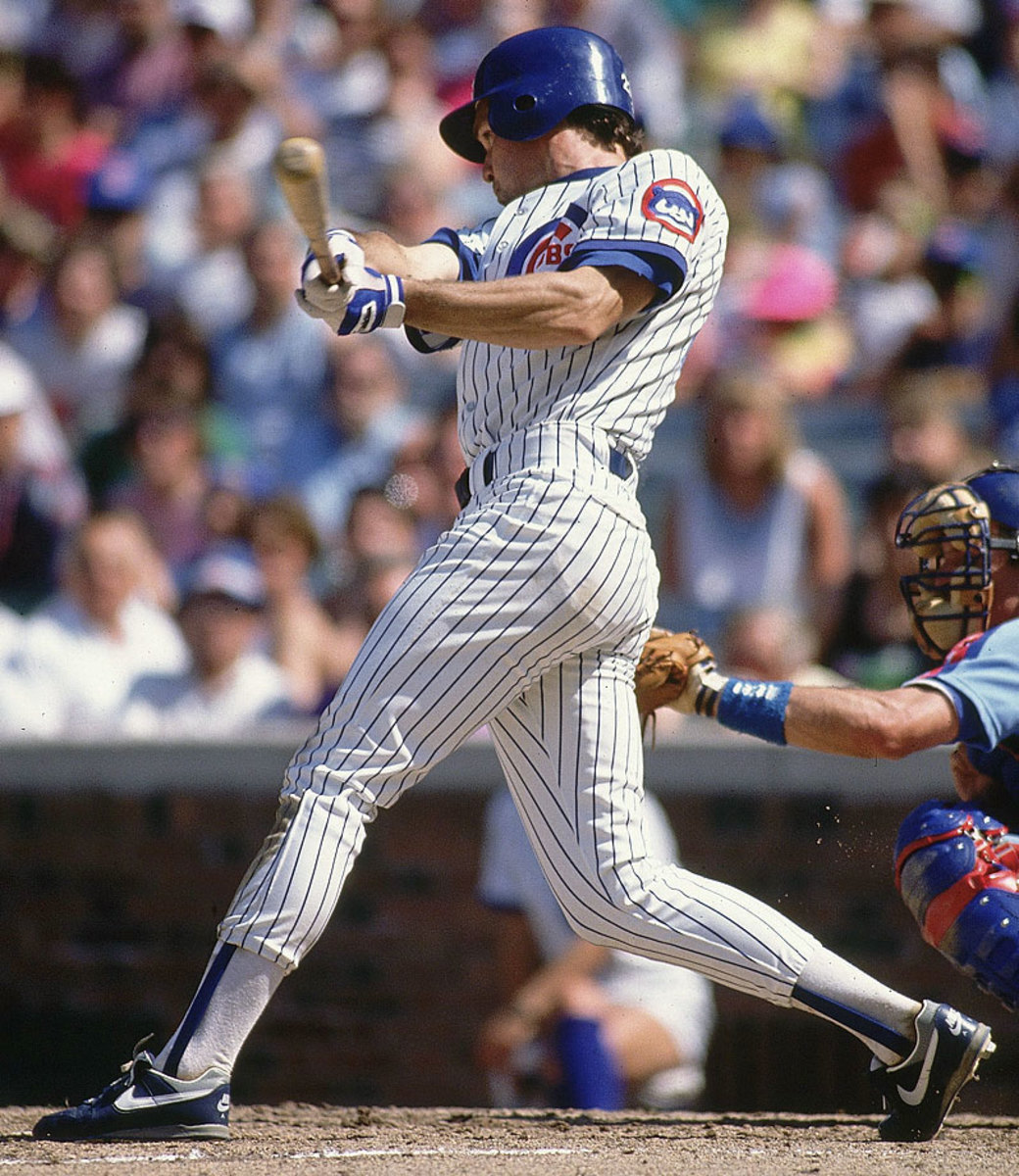

Second Baseman: Ryne Sandberg

His 282 home runs are more than 200 better than the next-highest second-sacker, which is just one reason the Hall of Famer is an easy call at this spot. His 10 All-Star berths, nine Gold Gloves and MVP-winning season in 1984, when the Cubs reached the postseason for the first time since 1945, are nice bonuses.

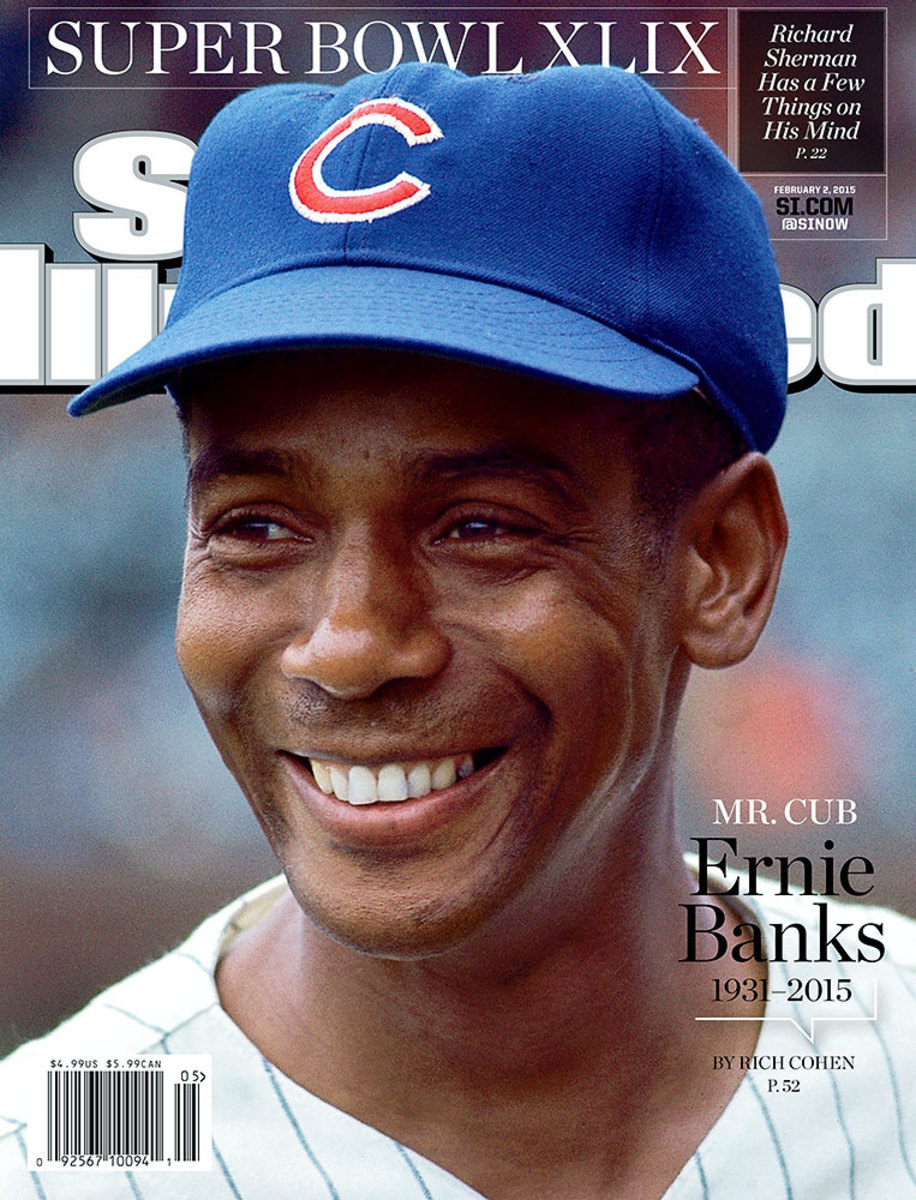

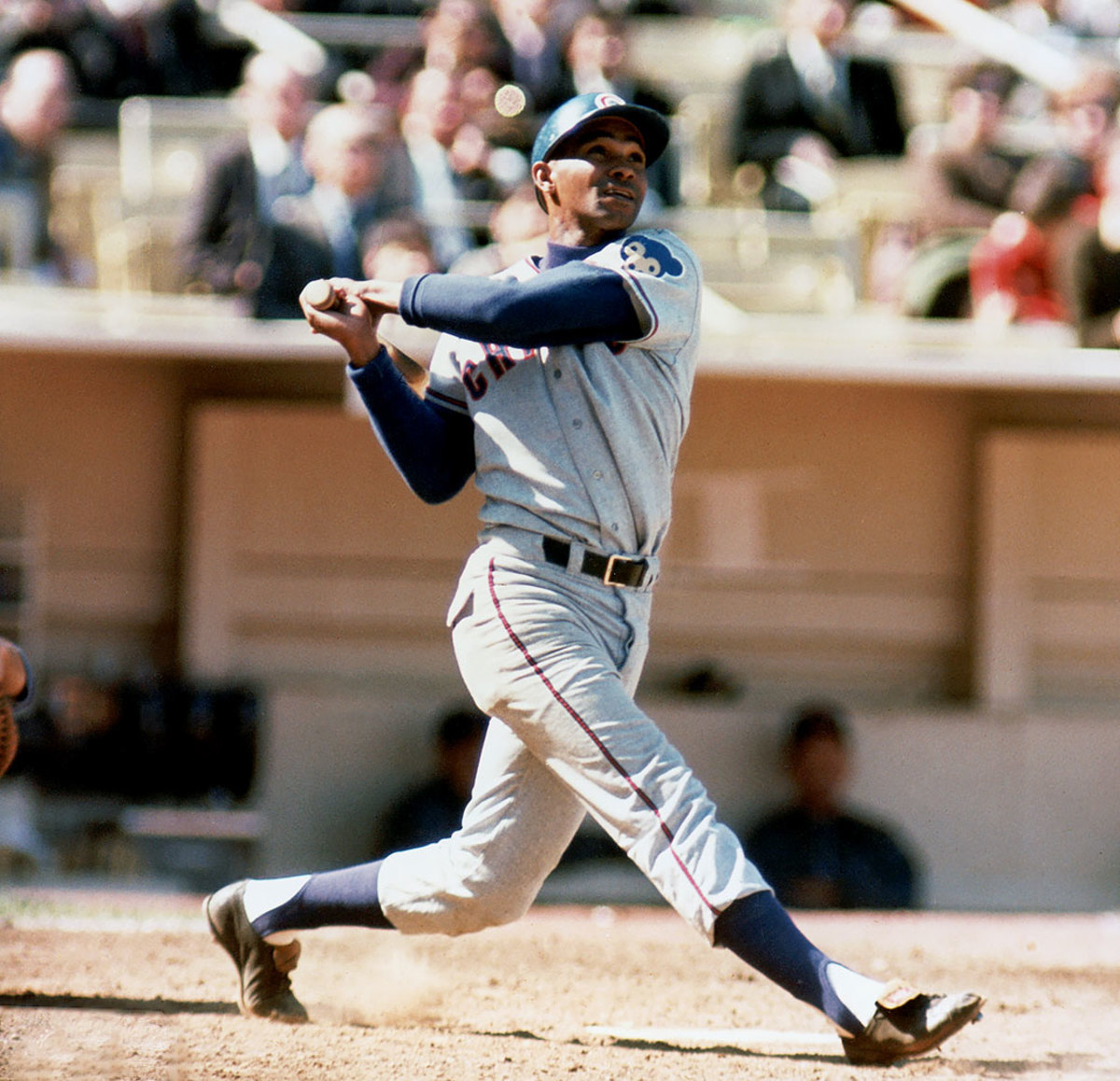

Shortstop: Ernie Banks

Banks won two MVPs and hit more than half his 512 career home runs while playing shortstop. He still ranks first in Cubs history in games, at-bats and heartbreak, for having played the most games in major league history without reaching the postseason.

Third Baseman: Ron Santo

Controversially left out of the Hall of Fame until after he died at age 70 in 2010, Santo was a mainstay for 15 years in Chicago, from 1960 to ’74, making nine All-Star teams, winning five Gold Gloves and leading the league in walks four times.

Leftfielder: Billy Williams

The 1961 NL Rookie of the Year hit .300 five times, made five All-Star teams and had a streak of 1,117 consecutive games played from 1963 to 1970 that still ranks as the sixth-longest in MLB history. Williams was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1987.

Centerfielder: Hack Wilson

His 191 RBIs in 1930 remain the single-season major league record and came in a year in which he also hit 56 home runs and posted a 1.177 OPS. Though he only spent six years in Chicago, he is still the franchise leader in on-base percentage and slugging percentage. He made the Hall of Fame in 1979, 31 years after he died.

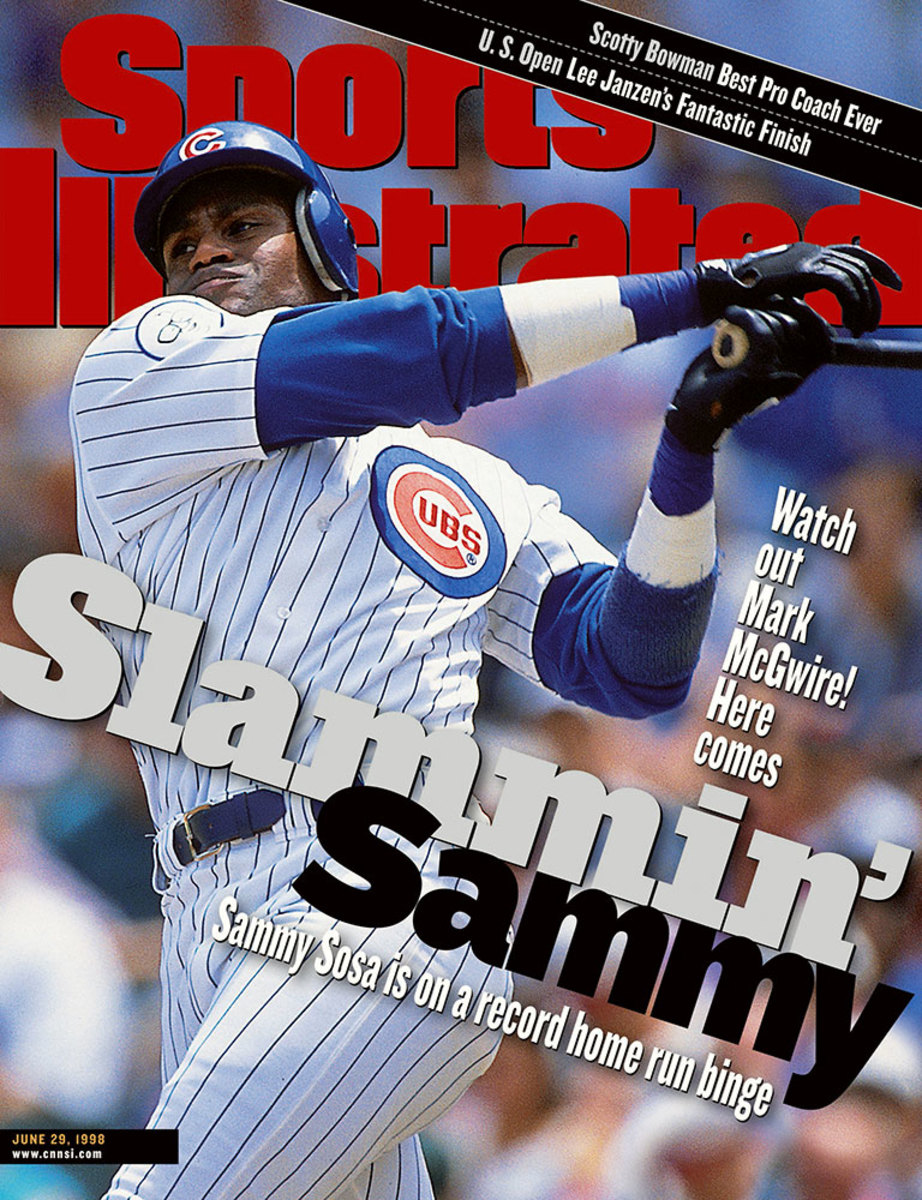

Rightfielder: Sammy Sosa

Corked bats and PED allegations aside, no player made Wrigley Field hop like Swingin’ Sammy. His absurd home run totals—including 66 in 1998, 63 in ’99 and 64 in 2001—overshadowed a well-rounded player who hit .300 four times and had seven straight years of 15 or more steals for the Cubs.

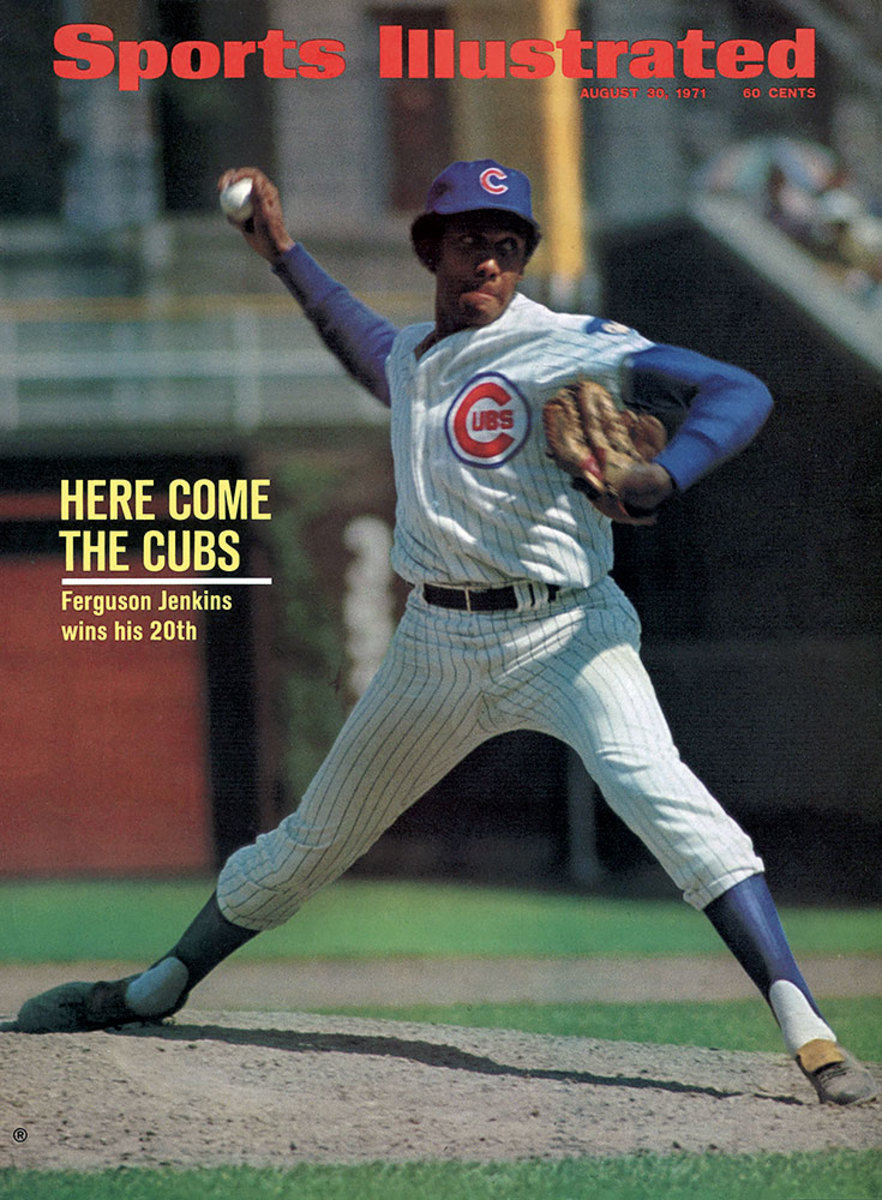

Starting Pitcher: Ferguson Jenkins

Jenkins arrived in a trade with the Phillies in 1966 at age 23 that soon became one of the most lopsided in baseball history. He won at least 20 games seven times and had five top-3 Cy Young finishes, including his win in 1971. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1991.

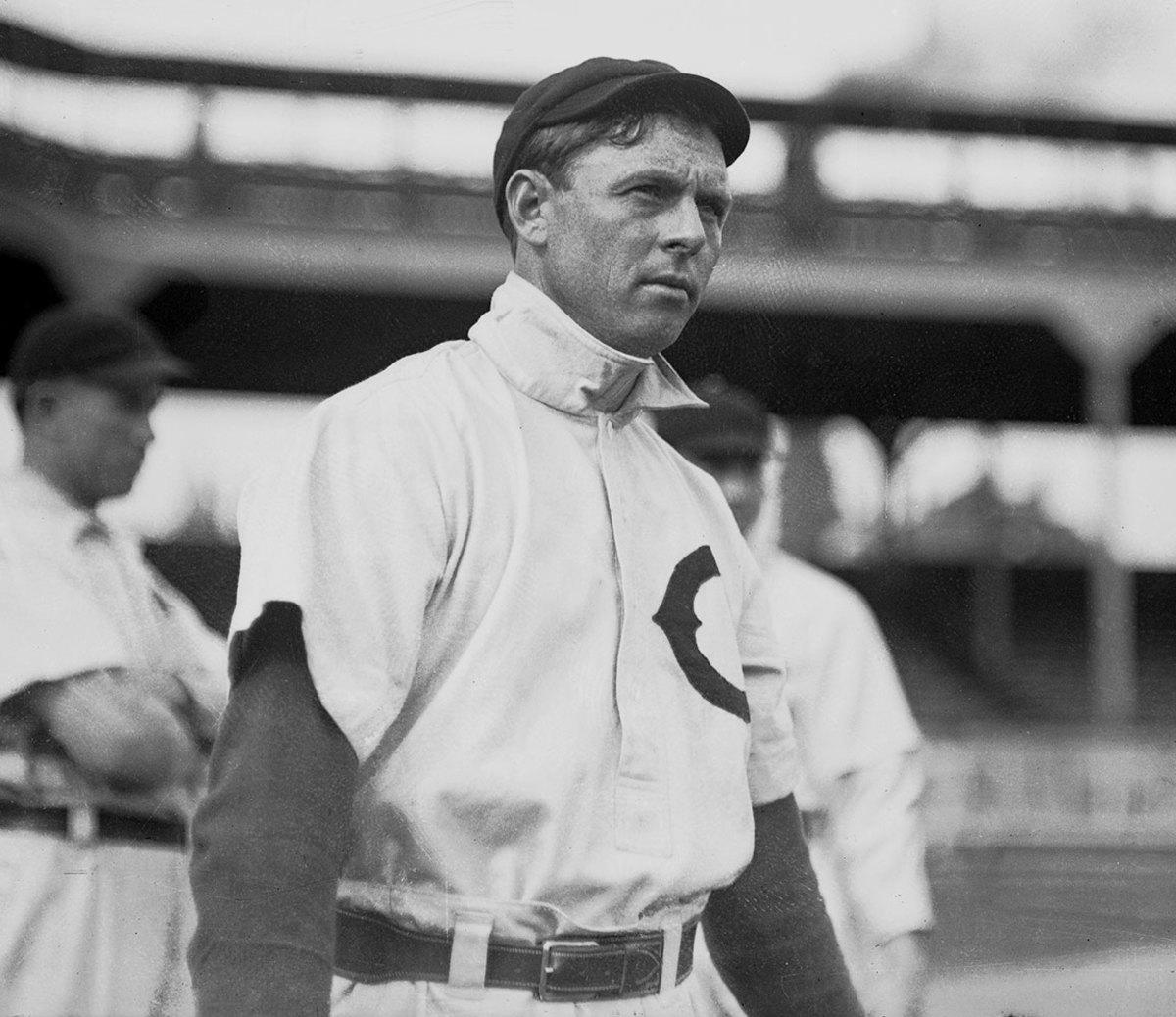

Starting Pitcher: Mordecai "Three Finger" Brown

A childhood accident mangled his pitching hand but didn’t stop Mordecai Brown from winning 20 or more games six times, posting a sub-2.00 ERA six times (including 1.04 in 1906) or making the Hall of Fame.

Relief Pitcher: Bruce Sutter

Though successor Lee Smith also had several standout seasons for the Cubs and holds the franchise saves record with 180, Sutter had the better career in Chicago, topping Smith in ERA (2.39 to 2.92), WHIP (1.05 to 1.25) and strikeout to walk ratio (3.32 to 2.44).

For Game 4, Rizzo returned to his own model. He whiffed on a Julio Urias fastball in the first and struck out again on another Urias heater in the third. In the fifth, with Baez on the mound, Rizzo returned to a piece of Szczur’s lumber. Szczur, an outfielder who is not on the active roster, didn’t even know Rizzo picked his bat out of the bat rack until he heard it on television later.

Naturally, Rizzo found a deeper meaning in his choice of wood.

“Szcz came out today with a nice [television] feature on him about him giving his bone marrow, so all the things were just adding up,” said Rizzo, who as an 18-year-old was diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma. “I hit well with his bat, so he has hits in it. Same size, just different model and different name, and it worked.”

On Sept. 2, the eight-year anniversary of Rizzo learning his cancer was in remission, he hit a home run against the Giants while fellow cancer survivor Lester nearly threw a no-hitter—the same day Rizzo hosted cancer patients as part of the work of his foundation. So, yes, the man is entitled to believe in forces deeper than simple superstition.

• 2016 MLB postseason: Complete schedule, TV listings, recaps

In addition to using Szczur’s bat, Rizzo changed his two-strike approach to hit the home run. With two strikes, Rizzo goes into protection mode in which he chokes up on the bat, ditches his leg kick and shortens his swing. He does so because he hates striking out. But this time, with two strikes, Rizzo remained in full-throttle mode instead of downshifting. He kept his leg kick, kept his hands as far down the handle of the bat as possible and took a full, healthy swipe at the baseball.

“I just did something I felt was comfortable at the time,” he said. “It’s hard to explain but it just felt right.”

His eighth-inning single, though less prodigious, was built on the same dynamic: a rare full-throttle two-strike swing with a Matt Szczur model bat.

The bat switch just might take its place in historical annals of home runs like the one in 1978 by Yankees shortstop Bucky Dent, who used a Mickey Rivers bat to break the hearts of the Red Sox. Its place in perpetuity will depend on whether Chicago wins two more games in this series.

Watching NLCS Game 3 with—and getting stories from—the ultimate Cubs fan

The series has played out as expected: The Cubs, because the Dodgers can’t hit lefthanded pitching, must win the games Lester starts (they did, in Game 1); and Los Angeles, because Clayton Kershaw is the best pitcher in baseball, must win the games Kershaw starts (they did, in Game 2). That leaves three non-Lester, non-Kershaw games to decide the series. So far the teams have split the first two of those three toss-ups games; the third one would be Game 7.

Dodgers manager Dave Roberts toyed with the idea of starting Kershaw on short rest against Lester in Game 5, but after his team won Game 3, he told Kershaw that he would be pitching Game 6. A start today by Kershaw would have meant five games for him in a span of 14 days.

“At some point,” Roberts said, “you have to understand that he’s human. Guys have got to pick up Kersh. He can’t do it all alone.”

Roberts’s perspective is to be applauded. By being prudent, he will now have a fully rested Kershaw lined up for Game 6, either to clinch L.A.'s first pennant since 1988 or to stave off elimination to force a seventh game. Either way, it’s a wonderful security blanket.

Eighteen years ago, the 114-win Yankees, staring at the abyss on the wrong side of a two-games-to-one deficit on the road in Cleveland, found equilibrium in the ALCS by beating the Indians, 4–0. As it happened, the lefthanded-hitting first baseman for those Yankees was slumping and broke out in that game. Mired in an 0-for-19 spiral, Tino Martinez rapped a double and a sacrifice fly, the start to hitting .368 over the rest of the postseason. The Yankees never lost again that year, running the table with a 7–0 streak.

It remains to be seen whether Game 4 was the start of a similar stretch for Rizzo and the Cubs. But this much is true for now: With Rizzo back, Chicago, to the chagrin of the whiteboard author in the Dodgers' clubhouse, is having fun again.