Dinner with DiMaggio: What it was like chatting with the Yankee Clipper

The following is excerpted from DINNER WITH DIMAGGIO by Dr. Rock Postiano and John Postiano. Copyright © 2017 by Dr. Rock Postiano and John Postiano. Printed by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Yankee Clipper held strong opinions on his fellow athletes. I discovered that he had two sports heroes: Muhammad Ali and Lou Gehrig.

During dinner one night, we had a major disagreement when I criticized Muhammad Ali for being, in my eyes, a draft dodger. I was touchy about the subject, because we had lost our cousin Michael Sessa Jr. during his second tour of duty in Vietnam. His sacrifice had affected his family deeply. After I stated my opinion, Joe turned pensive. He told me that Ali was a hero, and that he admired him. When I objected, Joe explained his position.

“Doc, you’re not supposed to be judging the guy in that arena. You’re supposed to look at him as a fighter, an athlete.”

I continued to argue.

“Listen, Doc,” he countered, “I may not have agreed with what he did, because I am a veteran myself, but Muhammad Ali is an athlete. He’s one of the greatest ever. In fact, he was as good as me.”

That is something I had never heard the Yankee Clipper say.

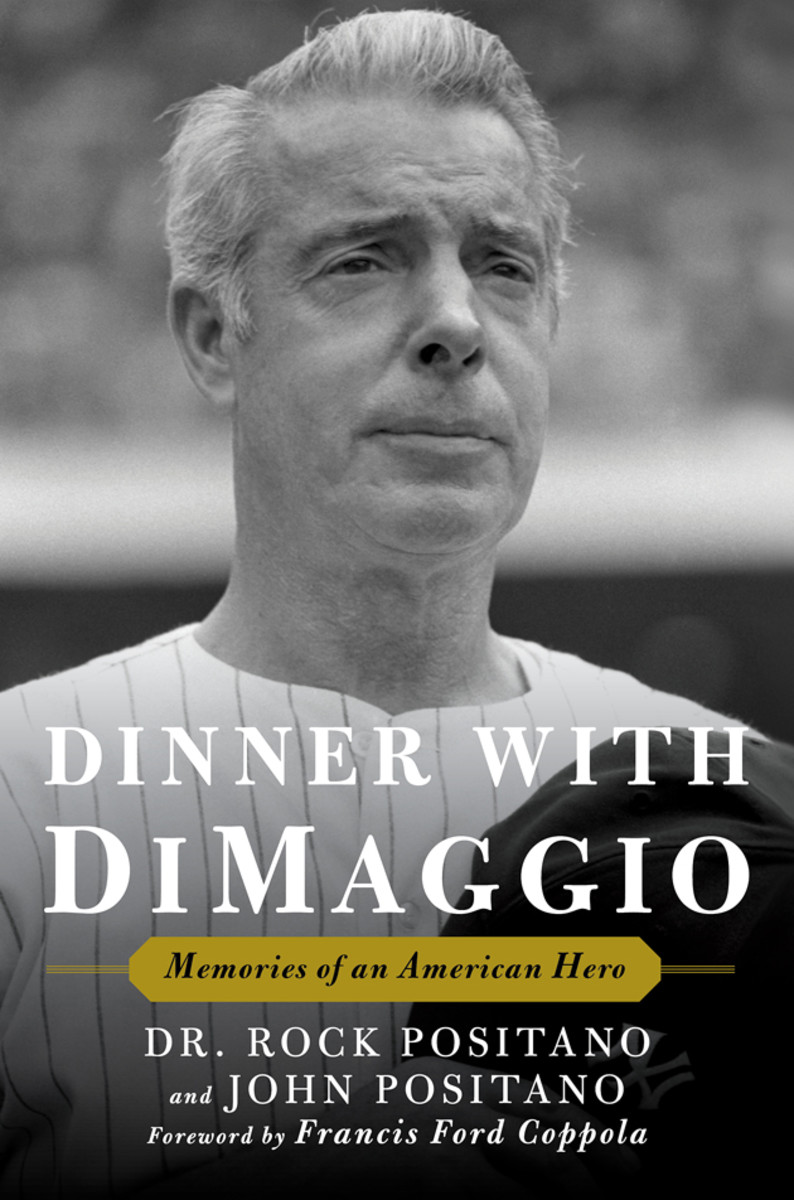

Buy Now

Dinner with DiMaggio

by Dr. Rock Positano and John Positano

An intimate portrait of an American Hero, with little-known stories about baseball icons, Marilyn Monroe, Frank Sinatra and more.

Joe continued to compare himself to his hero, Muhammad Ali: “People could have said the same thing about me. I served for three years at the peak of my career during World War Two, but I didn’t fight. Think of how that time away from playing affected my numbers. I never had a missile fired over my head or a bullet whizzing past my ear. I went around the world doing exhibition games for the troops.”

Joe reached for a breadstick, and continued, “And they could have said the same thing about Elvis Presley. He never saw a day of action. All he did was go from camp to camp to entertain the troops.”

“Well, Joe, what are you trying to tell me?”

Joe took a minute to respond. “I think that Muhammad Ali was the greatest. He was a fabulous boxer, a fabulous athlete, and that is what we should remember him for. When you judge people professionally, base it on their accomplishments in their area, not for what they believe or what they say and do in their personal lives.”

Joe’s other major hero was his predecessor, Lou Gehrig. Lou was as reticent as Ali was garrulous. Lou, a first baseman, is remembered more today for the disease that killed him than his athletic ability. Lou was vibrant in Joe’s memory. Joe was impressed that Gehrig had attended Ivy League Columbia University for two years before he dropped out to join the Yankees.

Video: New Yorkers read Derek Jeter’s love letter to the city

Lou and Joe shared adjacent lockers during Joe’s rookie season with the Yankees. Joe remembered him as an intelligent and shy man. He compared Lou’s strong, stocky legs to piano legs that were matched by a body builder’s upper torso and Popeye the Sailor-Man forearms. But Lou wasn’t muscle bound. According to Joe, Lou had agility as well as strength.

Joe told me that when Lou hit a line drive, it was as though the ball was attached to a taut rope. “It would take off like a rocket and ping off the facades and bleachers of the Stadium in right field. You could hear the balls all the way in the Yankee clubhouse ringing like a bell when Gehrig was in batting practice,” Joe said with admiration.

Lou’s advice to the rookie was straight and powerful. Joe told me that Lou’s example had guided him to develop valuable personal attributes—in Joe’s words, “being dignified, never speaking out of turn, conducting myself properly under any circumstances, and, most important, not volunteering any information to the wrong people.” These lessons were Lou’s direct contribution to Joe’s nascent legend.

Lou was keeping a brother’s eye out for Joe. The rookie was under the impression that his teammate was there for him at all times, but Lou was suffering from the initial, barely noticeable, symptoms of the disease that would overwhelm him.

Joe first noticed that Lou had started to shave unsteadily. Then Lou had problems tying his laces. Joe noticed Lou dropping things.

By 1937, Lou seemed slow and even more deliberate. Despite what he was observing, Joe said nothing to anyone. Joe chalked it up to Gehrig’s having another slow start in spring training, which was a common occurrence.

Eventually, that something was seriously wrong with Lou became apparent. He couldn’t hit well and was having trouble fielding and getting around the bases. It got so bad that Lou was dropping the bat in the batter’s circle, had problems with his glove, and wasn’t up to the tactics of the opposing team.

One day, he and Lou were talking alongside their lockers. Joe told me that he would never forget it.

“Lou said to me, ‘Joe, I don’t think that I can play baseball anymore. I want to take myself out of the lineup before McCarthy takes me out.’”

The Clipper was shocked by Lou’s words. He had told no one else on the team what Lou was going through.

Decades later, thinking about the conversation made Joe tear up.

“Doc, this was the first time I ever showed any emotion inside the locker room. It was just the two of us, alone, and Gehrig started to cry. I cried, too.”

I could see the pain in Joe’s eyes even fifty years later.

Joe had kept his mouth shut about the growing evidence of Gehrig’s infirmities. He was the stand-up guy’s stand-up guy. Dignity had to be maintained.

The Papi Papers: How David Ortiz endured the most difficult year of his career

Just as Joe was quick to praise his heroes and those he admired, he was outspoken in his criticism of other legends. He once made a comment about Don Larsen. Joe was amazed and perplexed that Larsen’s performance in one game in the 1956 World Series, a perfect no-hitter, immortalized him in the sporting world for the rest of his career. On the basis of a single game, Larsen received a lot of attention and accolades.

I went with Joe to the Yankees’ Old Timers’ Game in 1994. Retired Yankees were asked to come to the stadium to make an appearance for their fans. This was a big deal for Joe. He did it for the fans, not for the owner or the Yankees.

By 1994, he no longer wore the Yankee uniform, because his body was showing signs of aging, and he didn’t like the way he looked in it. As usual, Joe was perfectly turned out in a well-tailored navy blue suit and tie. He often criticized his former teammates, Rizzuto, Berra, and Mantle, for their poor appearance in uniform. He was less harsh about Phil and Yogi. He expressed his firm opinion that the elder Yankees should show up in suits for Old Timers’ Games and other events.

On our way up to the owner’s box in an elevator that day in 1994, we stopped between the ground level and the box floor. The doors opened, and there was Mickey Mantle. I didn’t recognize the stocky, strong-looking guy in a warm-up suit for a full five seconds, but Joe did immediately. He gave Mickey a stern look.

An eternity passed in those minutes. Both men were avoiding eye contact, looking anywhere but at each other. Joe was waiting for The Mick to blink and acknowledge him first. It was a pecking order thing or the ballplayer’s version of chicken. Mickey was the first to break the painful silence between the legends.

“How ya doin’ Joe?” Mickey asked with his eyes down.

Joe studied Mickey. “I’m okay, Mick.” He paused before asking, “You stayin’ out of trouble?” Neither man spoke after that. When Mickey left the elevator, Joe turned to me and commented, “Doc, some guys just never learn. He will never change.”

That was the longest elevator ride I ever took. It seemed endless. The tension was indescribable and something right out of High Noon.

The Clipper did not let go of the grudge. As Mickey Mantle was dying of cancer, I thought Joe would relent. It didn’t happen. Joe never forgave Mantle for replacing him in center field and not taking his advice about how to conduct himself as a Yankee. Despite getting updates on Mickey’s condition, which was bad and worsening, Joe would not soften.

When I ventured to ask him about it, he said, “You know, Doc, I don’t really feel sorry for the guy. He did it to himself.”

He could be a very tough man.

Joe made himself unavailable to the press seeking his words to honor the dying and departed Mickey Mantle. It fell on me to pass press requests to Joe, who declined all of them. Even at a posthumous Mickey Mantle Day at the Stadium, Joe did nothing more than show up. I found his behavior disturbing.

Manny Machado, Kris Bryant, Bryce Harper among the faces of every MLB franchise

He told a Steinbrenner special assistant, Brian Smith, that he had no intention of talking about Mickey. “You make sure they know that I am not getting up to that mike to say anything about anybody. I was asked to come here to show up and walk out on the field. That is exactly what I am going to do. Then I am going to turn back and walk off the field.”

I was surprised by how rigid and bitter he allowed himself to appear. People remember that sort of behavior. It seemed so petty to me, but what I thought didn’t matter. I was disappointed that he dug in. He should have been bigger than that. He expected others to rise above their grudges.

A few minutes later, Joe DiMaggio stepped onto the playing field with the other ballplayers. He got the lion’s share of the applause. Then he turned tail, walked off, and headed home.

“Come on, Doc,” he commanded, “we’re getting the hell out of here.” And so we did.

Joe’s wrath extended to others as well, including George Steinbrenner, the owner of the Yankees and a sharp businessman. Though very fond of Steinbrenner personally, Joe was never quite comfortable with him, because Steinbrenner was always asking him for some favor, whether to work out a baseball memorabilia deal or to meet people who would help advance the business interests of the New York Yankees.

Steinbrenner was obsessed with DiMaggio. He considered Joe a good luck charm. He believed that the Yanks couldn’t lose if the Yankee Clipper was in “the house that Ruth built.” When the Yankees were in the playoffs in 1996, George made sure that Joe was at the games, sitting in what was nominally George’s box, which wasn’t the case when Joe was in attendance.

George was intent on commissioning a statue of Joe to be placed in center field at the stadium. He even tried to get another statue of Joe planted in Central Park. There was only one problem. George needed Joe’s blessing. It was a respect thing.

Joe was adamantly against being memorialized anywhere in New York while he was still in the upright position.

“As long as I am still walking,” he insisted, “there is no way I will have anyone build a statue of me in this city. When I am dead, they can do whatever the hell they want.”

It was a closed issue. Joe told George no, and that was it.

In fact, Joe vetoed every statue and monument, as well as East 56th Street, which New York City tried to name after him. On a drive to Yankee Stadium on the Deegan, Joe told me that the city had offered to rename the Major Deegan the Joe DiMaggio Expressway. The expressway in the Bronx passes right by Yankee Stadium and leads to the New York State Thruway. Major William Francis Deegan, a buddy of Mayor Jimmy Walker, served in the Army Corps of Engineers and built many local Army bases.

“I told them no, because I felt it was disrespectful to Major Deegan’s memory,” he explained. “I won’t have them knock his name off to replace it with mine. It wouldn’t be right, and I wouldn’t feel good about it.”

Soon after the confrontation about the statue in center field, we were invited back to Steinbrenner’s box. In all fairness to Steinbrenner, he always went out of his way to make Joe feel at home. He made sure that Joe had his Bazzini shelled peanuts and Cracker Jacks in the owner’s box. During this visit, George had a new food vendor who made Philadelphia cheesesteaks. He persuaded us to try them out. Joe was resistant to trying anything new. He was a culinary snob. The thought of eating a premade cheesesteak didn’t sit well with him, but he enjoyed it.

Not long after finishing, he turned to me with visible discomfort and said, “Doc, we better get out of here soon. My stomach is really bothering me. I have to get back to Burke’s place.”

We sped back to Manhattan in under fifteen minutes. Joe made it to the bathroom just in time.

From behind the bathroom door, Joe started yelling. “Doc, I don’t know what the hell Steinbrenner fed me, but I think he’s trying to kill me so he can put up that statue of me in centerfield.”

I think he believed it.