Remembering my grandfather, a World War II vet and former minor league baseball player

I never met my paternal grandfather, Harry Alvin Swartout. He died when my dad was just 12, but I knew two things about him: He fought in World War II and he played minor league baseball. For Memorial Day this year, I decided to finally learn more about my grandfather, and accidentally discovered an entire generation of would-be pro baseball players who sacrificed their shot at the big leagues to fight for America.

When my Grandma died a few years back, she left us a trunk filled with smoky, dusty papers and mementos, everything from the 1969 newspaper featuring the moon landing to bowling league membership cards. At the bottom, under a large box of costume jewelry, Grandma had buried Grandpa Harry’s heirlooms, essentially all that was left of his legacy. Harry Alvin would have been 93 this year and all of his close family and everybody he mentioned serving or playing ball with has died. The documents are what we have left.

Before he went to Bethlehem Central High School in Delmar, N.Y., and lettered in baseball, football, basketball, bowling, golf and track, Grandpa played little league ball. The oldest document in the trunk is a picture of the AL pennant-winning 1934 Detroit Tigers. On the back, Harry Alvin wrote a letter to his mother “Dad said I could play ball. Dad said to start home at 5:30, Harry. XXXXX.”

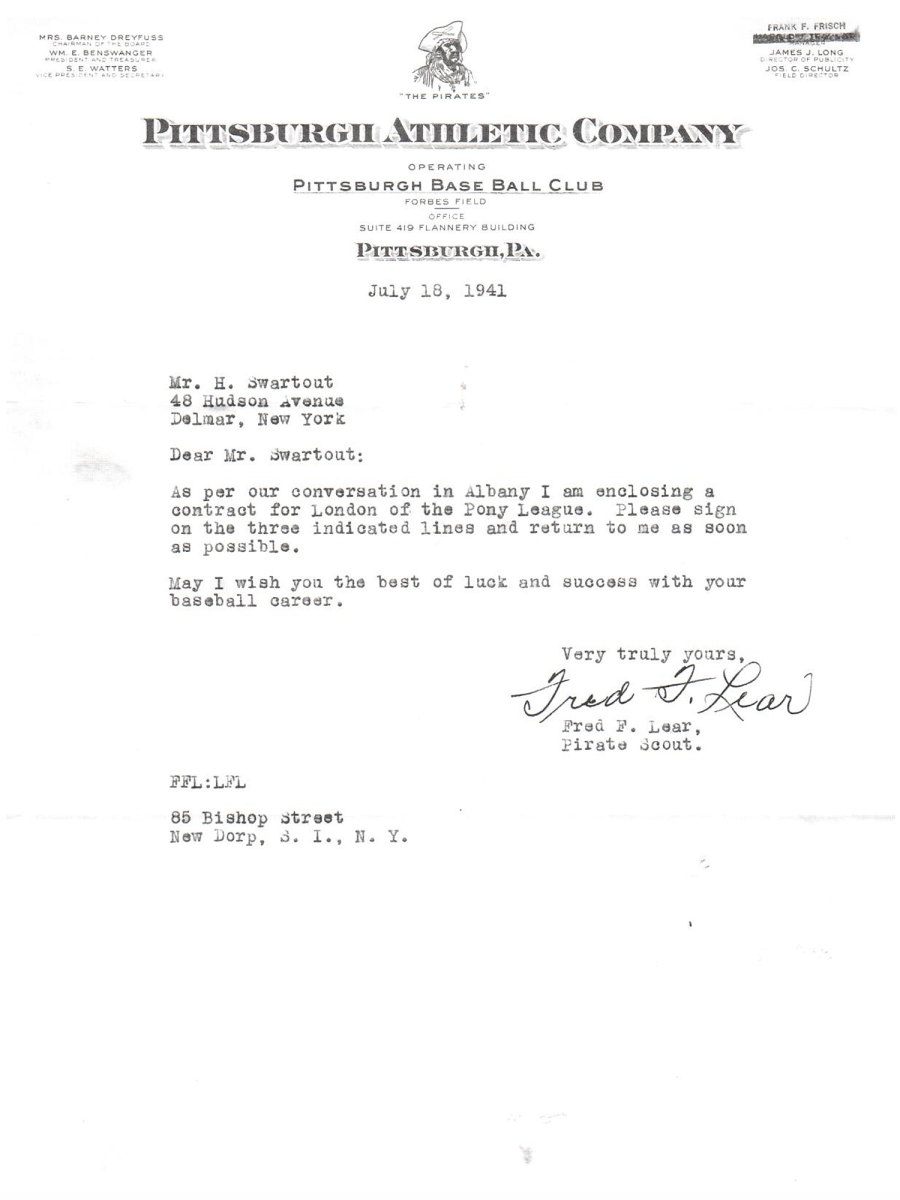

In his junior year of high school, Harry was scouted by Fred Lear of the Pittsburgh Pirates, himself a former MLB player.

He signed with the London Pirates of the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York league (PONY league for short) and played pro baseball while he was still in school. With 43 leagues nationwide and hundreds of teams, this was a common first step in a professional baseball career. Young hopefuls would sign with their local team and try to attract the attention of a scout, but coming out of school directly into the minor leagues during wartime was a bit different.

Many of the minor leagues had shut down after the U.S. entered the war. Those that remained had an ever-fluctuating roster because players were constantly being drafted into the military. It appears that the Pirates stashed Grandpa on the bench (a common practice for the youngest talent while the draft was in effect), so he could play exhibition games and practice with the team while not taking the spot of a valuable veteran who had not heard his name called for the draft. It seemed by 1943 he would be a starter . . . if he had not enlisted in the Marines.

By 1944, Harry Alvin was in the Pacific. He had risen to the rank of Staff Sergeant and had several flying missions. He would frequently draw out maps of the islands he flew over, complete with military positions and pieces.

But his biggest pastime when not in the air was baseball. Harry Alvin joined the headquarters team for the military league that had been started on Okinawa.

All over the Western front, U.S. Army, Navy, Marines and Air Force units set up make-shift diamonds wherever they had space. Venues in the jungles and on beaches were dotted with players in their military uniforms having a catch and playing the national pastime.

Servicemen even kept track of the teams' exploits in the military news bulletins, which published write-ups and stats of the military games alongside the MLB games being played back home.

The MLB stars that went to war even gathered onto military base teams that looked more like All-Star squads than army squadrons. Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Johnny Vander Meer and Hank Greenberg all suited up for base teams and even toured the islands playing games to entertain the G.I.’s. Most big leaguers were kept off the front lines, but minor leaguers ended up wherever they were needed.

In all, 125 minor league baseball players died in service. Countless more were wounded physically and even more came back with psychological trauma. For those that did make it out of the service, they returned to a minor league landscape much different than the one they had left. Leagues swelled with returning men, forcing players at all levels to have to fight for their roster spot. Some found that their skills eroded from neglect during the war. Others couldn’t concentrate on the game. Even more decided to use the GI Bill to get an education instead. This is what Harry Alvin did.

Within a year Harry was married and within two he had a child. He played his last game of semi-pro baseball in 1949, the same year he graduated from Syracuse University, with a local team in nearby Greenbush, N.Y.

After moving into the work force, Harry Alvin kept baseball in his life by watching it and by buying merchandise. He saw where the sports market was going and became the sports buyer for the W.T. Grant Company (a Sears-like department store). He taught his four children how to play the game and had a dream of owning a sporting goods store in Florida when he died in 1966.

Under his life goal in his high school yearbook, Harry Alvin wrote "play professional baseball." He never really got the chance after America asked him and thousands like him in his generation to defer such dreams in order to fight for something bigger: The American Dream.