Six Years Ago, the Bankrupt Los Angeles Dodgers Were in a Very Different Place

The following is adapted from THE BIG CHAIR: The Smooth Hops and Bad Bounces from the Inside World of the Acclaimed Los Angeles Dodgers General Manager by Ned Colletti with Joseph A. Reaves, published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2017 by Painting the Korners, LLC.

Harvard Business School should teach a course on the business acumen of Frank H. McCourt Jr.

It seemed that not many Dodgers fans liked the man. The commissioner of baseball seemed like he despised him. But there is no denying Frank’s staggering business skills.

Frank came from a very successful family. His great-grandfather, an Irish immigrant, founded the John McCourt Company, which quickly became one of Boston’s most respected road-building companies. His grandfather once owned a piece of the Boston Braves while expanding the family business into one of the top highway construction companies in New England, at a time when Americans were becoming increasingly dependent on the automobile.

The Big Chair

by Ned Colletti

An unprecedented, behind-the-scenes look at the career of famed former Los Angeles Dodgers General Manager, whose tenure spanned nine of the most exciting and turbulent years in the franchise’s history.

Frank’s father served with the Fourteenth Armored Division in Europe during World War II and returned to shepherd the McCourt Company’s transition from road builders to general contractors, overseeing more sophisticated infrastructure projects, including the expansion of Boston’s Logan International Airport.

After graduating from Georgetown University, Frank McCourt Jr. established his own company and quickly made his mark, acquiring twenty-four acres of waterfront property in South Boston from the bankrupt Penn Central Railroad in the early 1980s and turning the land into lucrative parking lots while he waited for even more lucrative development opportunities.

In 2001, at age forty-seven, McCourt made a bid to buy the Boston Red Sox, offering ten acres of his waterfront property for use in building a new ballpark to replace historic Fenway Park, which, at the time, was deteriorating badly.

“Clearly the land is much more valuable for full-time commercial and residential development,” McCourt told The Boston Globe in August 2001. “So the only rationale that would motivate us to take on a less-valuable ballpark project would be if it was fused with a controlling interest in the team.”

That proposal quickly fell flat, but two years later, Frank made another bid to buy the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim, losing out to Arte Moreno, who became the first Mexican American to be the primary owner of a Major League Baseball team.

On January 21, 2003, News Corporation put the Dodgers up for sale. Allen & Company, a New York–based company that specializes as an investment banking and advisory firm, helped broker the sale.

For six months, News Corporation courted Malcolm Glazer, the billionaire owner of the National Football League’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers and the Premier League’s Manchester United, who died in 2014. Both sides tried hard to reach a deal, but the NFL’s crossownership rules made it impossible. (The NFL allows its owners to purchase sports franchises outside the United States, but banned cross-ownership of teams within the country.)

The prolonged negotiations only made News Corporation all the more impatient to sell the Dodgers and played right into Frank McCourt’s hands. On October 10, 2003, Rupert Murdoch’s Fox media conglomerate agreed in principle to sell the Los Angeles Dodgers to McCourt for approximately $431 million. The deal, which was approved by Major League Baseball on January 29, 2004, was highly leveraged—so leveraged that longtime local radio talk show host Joe McDonnell of KSPN stopped using McCourt’s name and started calling him “McBankrupt.” That was just days after the sale and a full seven and a half years before Frank actually filed for bankruptcy. It was a sign that from the very beginning the media were bent on giving the McCourts a tough ride.

There was a curiosity about how leveraged the deal was and few really knew until Frank and Jamie’s divorce trial, when Frank’s attorney, Steve Susman, acknowledged publicly that “not a penny” of the McCourts’ own money went into the deal.

Not a penny of his own money?

And eight years later, he sold the team for $2.15 billion. Billion! That’s a pretty good return on investment. I’d call it McBrilliant. Worthy of a course at Harvard Business School.

Frank and Jamie took over the club in February 2004. Within two months, they bought a home in the Holmby Hills portion of Brentwood, near the University of California, Los Angeles campus in Westwood, and a few hundred yards from the main gate to Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Mansion. They paid $21.25 million for the five-bedroom, six-bathroom, 11,637-square-foot mansion, then spent another $14 million on renovations that included an Olympic-sized indoor swimming pool—Jamie was an avid swimmer—and transporting the entire kitchen from their Massachusetts home. For good measure, a few months later the McCourts bought a neighboring house for $6.5 million with the intent of using it as a guesthouse. Media, citing divorce documents, reported the McCourts spent an additional $4.8 million in basic improvements and architectural fees to that property.

The first year they owned the Dodgers, the team made the postseason for the first time since 1996. Then things went south. After losing three of four to the St. Louis Cardinals in the 2004 National League Division Series, the 2005 team started 12-2, only to stumble to a 71-91 record—the second-worst record by any Dodger team since World War II. General Manager DePodesta and Manager Jim Tracy weren’t seeing eye to eye. Outfielder Milton Bradley had a series of high-profile run-ins with his teammates and fans. The franchise was in dire straits.

As the 2005 season was winding down—unbeknownst to either one of us, it would be Paul’s last with the Dodgers and my last with San Francisco—the Giants were playing the Dodgers in Los Angeles the first few days of September 2005. My son, Lou, and I decided to drive over from Phoenix, where the Giants had just finished a series against the Diamondbacks and Lou had wrapped up a season coaching at the rookie level. On our way to Dodger Stadium, Lou and I stopped for lunch. We sat down and heard a commotion coming from a raised row of tables nearly adjacent to us in the restaurant. It didn’t take long for me to recognize the voices. DePodesta and Tracy were having a respectful yet emotional exchange that would have best been kept private, not carried out in a popular Pasadena restaurant.

Little more than a month later, Tracy and the Dodgers parted ways and Paul was let go with three years remaining on his contract. I had replaced Jim with Grady Little. We turned the 71-91 debacle into a team that won 88 games and went to the postseason. Frank and Jamie were ecstatic. Two of their first three teams had made the playoffs. Attendance was healthy. So were sponsorships. Healthy enough for the McCourts to go shopping again.

In 2007, the McCourts added a $27.3 million beachfront home previously owned by Courteney Cox and David Arquette at Carbon Beach in Malibu. The home had eighty feet of private beach. Frank and Jamie bought the neighboring house in 2008 for $19 million.

According to media reports from divorce documents, the L.A. homes were added to a portfolio of properties in Vail, Colorado ($6 million), Cabo San Lucas, Mexico ($4.6 million), the Yellowstone Club in Montana ($7.7 million), and a one-hundred-acre Cape Cod estate that at one point was on the market for $50 million.

Life was good for Frank and Jamie, as the public divorce reports displayed. Late evening dinners in Brentwood, Bel-Air, and Beverly Hills. Personal drivers, private jets, expensive daily hairstylists, florists, a “healer” in Massachusetts, and a staff of assistants at their home and at Dodger Stadium.

In 2008, the Dodgers advanced to the National League Championship Series, against the Philadelphia Phillies. We lost in five games but the following year played the Phillies again in the NLCS. In the moments immediately before the opening of the 2008 NLCS, I ran into my first baseball boss—Dallas Green, at that point a special assistant in the Phillies front office.

We saw each other in a hallway. He came toward me with outstretched arms and we hugged.

“I am so very proud of you, Colletti,” Dallas said. “You’ve done very well here.”

I thanked him. His words meant a lot to me since he provided me with my first baseball opportunity.

“But make no mistake, we are here to kick the Dodgers’ ass.” Ah, yes. The same man I knew twenty-six years earlier.

Then, on the eve of the 2009 NLCS, the marital cracks began to reach the public. Media speculation had been rampant that the McCourts were having issues. They were seldom seen together. I had been trying to block it all out, but the night before Clayton Kershaw would match up against Cole Hamels in Game 1 at Dodger Stadium, I was with a friend, Bill Connor, who had worked for decades on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson and Jay Leno. We were dining at Morton’s near the NBC lot in Burbank and I’d just sat down when Frank called.

He told me they were separating and he wanted me to know ahead of the news reports.

I thanked Frank for the heads-up and within days the firestorms erupted. The fire would burn for nearly three years.

On October 16, the day after we lost the series opener 8–6, Frank and Jamie each publicly declared ownership of the team— Frank claimed 100 percent ownership. Jamie said she was entitled to 50 percent under California community property law.

Six days later, the day after the Phillies eliminated us and moved on to the World Series, Frank fired Jamie as CEO of the Dodgers, telling her to clean out her office and report to Human Resources. I don’t remember ever hearing of a husband firing his wife. Publicly, no less.

On October 27, Jamie formally filed for divorce and demanded her job back as Dodgers CEO.

All those chaotic and headline-grabbing events were playing out as I was coming up to the fifth-year option I had negotiated when I originally signed. The deadline was October 31. We’d been negotiating a possible extension during the NLCS and amid all the ugly legal maneuvering. Without the fifth-year mutual option, the Dodgers would have had all the leverage. Frank could have taken the club option for the fifth year and left me in a weak negotiating position. But since I had an option, too, and other clubs were beginning to send out feelers, I had a touch of leverage. The Dodgers had gone to the postseason three of my first four years and were coming off back-to-back NLCS appearances for the first time since 1977–78. People had taken notice.

A position with another team was there for the taking if I wanted to leave, but there was something about the challenges of leadership and the competition in L.A. that fueled me. Although a different organization might have had less drama, and perhaps even as good a chance to be successful—if not better—I decided that if Frank would negotiate with me fairly, I would stay. Like a free agent deal for a player, I had done my research and felt I was prepared. I knew where my break point would be in deciding to stay or leave. The next move would be up to Frank and I was at peace with whatever his decision would be. He was still the best negotiator I had ever been up against, but I felt confident that between the respect we shared and the research I had done and explained to him, he would be fair and realistic. If not, there were options.

It was also important to me to be able to keep the staff together. They had earned the opportunity to stay and prosper. If I left, they would fall into the purgatory that comes with a new leader in the GM chair. I felt I owed them stability as well.

Besides taking the 71-91 team from 2005 and turning it into three postseason clubs, the organization had been very successful at the gate and we were making deadline deals without paying the salaries of players we were acquiring.

In the end, we settled on a three-year extension with a pair of one-year options—both club options. We signed the deal in the lobby of the Philadelphia Ritz-Carlton, which is a block from City Hall and about a mile or so west of where the Declaration of Independence was signed.

The day of the signing was an off day between Games 4 and 5 of the NLCS. I went to the meeting alone. Frank was there with Dennis Mannion, the club president; Sam Fernandez, the Dodgers’ legal counsel; Peter Wilhelm, CFO; and Jeff Ingram, a longtime aide to Frank in real estate and Dodgers ventures. The dynamics of that day are still very interesting to me. I was running a team trying to get to the World Series and managing 180 or so people in the front office while dealing with all the outside noise and uncertainty of the McCourts’ marriage and my own future. We were sitting at a table in the lobby with five men on one side of the table and me on the other side. Then, one night later, the Phillies beat us. The 2009 season was over and Frank’s fight to keep the team took center stage, and I had the additional task of walking a fine line of support to the people who hired me and maintaining credibility in the public eye.

A prominent sports columnist once told me point-blank that as long as I continued to support McCourt, he would do everything he could to make me look bad and damage my credibility and career. And he did at least try.

All you can do in a situation like that is live with it. In a job like the one I had, you live with a lot of things. You try to take the high road and be as classy as possible. Don Mattingly and I talked about that all the time after he became manager of the Dodgers. Focus on what you can control in a positive way.

Former Navy SEAL Mark Owen laid it out clearly when he said that the best focus on what they can control and stay within their three-foot world.

You keep those things riveted in your sight line—on your goal path. If we had gotten distracted by everything we dealt with during the McCourt era, we wouldn’t have had time to do anything but feel sorry for ourselves and bitch and moan.

Frank had his faults. We all do. But I truly relished my time with him, particularly our conversations. Frank is a sharp man—very, very intelligent. He would challenge my thought process constantly and relentlessly. In the beginning, he was more than a little intimidating. But I came to realize he was doing it for the good of the organization, and for my own personal growth. I would have an idea and tell his assistant, Hannah Shearer, I needed fifteen minutes. By the time Frank stopped grilling me, we’d be in there for an hour and a half or two hours. In the end, he nearly always agreed with me, and I remember asking him once, “What did I say to give you the confidence to agree with me?”

“I agreed with you before you walked in the door,” he said. “I just wanted to make sure you had thought it through and let you see how you had done it.”

That was an amazing ability. I miss those sessions.

In my opinion, the next two and a half years were the most tumultuous the Dodgers or, for that matter, any American major market sports franchise, ever endured. Frank and Jamie’s divorce trial led to a seemingly endless marathon of demoralizing news reports about their lifestyle, which the media used to question whether the team had the best chance to succeed. But those reports were only part of the landscape. Commissioner Selig went to war against Frank— MLB claimed publicly that $189 million had been “looted” from the franchise. It got mean and personal. MLB tried to take over the team and vetoed a television deal with Fox that Frank hoped would put the team on very solid financial footing.

As with any business leader, Frank wanted to make money, but he also wanted to be seen and respected as a “success.” He had a genuine passion for baseball and understood how privileged he was to own the Dodgers. Frank wanted to be seen as a good steward of the franchise. But each passing news report undermined any hope the fans and media would see him that way. All along the way, Frank fought every assertion.

On June 26, 2011, McCourt struck back. He had threatened to drag the commissioner and Major League Baseball into court, but held off. Then, over dinner with a trusted associate, he struck business genius. He decided to file for bankruptcy, a strategy that changed the course of events dramatically. The decision did not come easily. But it was his only choice.

“He fought the idea,” a longtime business associate offered. “It wasn’t something he had ever wanted to consider, but after having that dinner, there were a couple of discussions and then it was full on. In less than two weeks he had filed. It easily turned out to be the best choice.”

Frank hired the international law firm Dewey & LeBoeuf to lead the charge—an ironic move considering Dewey & LeBoeuf filed for bankruptcy itself and went out of business just two years after McCourt sold the team.

The bankruptcy move, which took less than a week to put into action once it began, gave Frank leverage and took potential control of the franchise out of the hands of Major League Baseball. No one I knew used leverage better than Frank McCourt. The United States Bankruptcy Court was now in control of the Dodgers, and, as is the case with most bankruptcies, the court has two primary goals: try to get creditors as close to one hundred cents on the dollar owed, and settle the case. Frank could argue strongly that the scuttled Fox deal offered creditors the best possible remedy.

The Dodgers missed the playoffs in 2010 and 2011, which is hardly surprising considering what we were dealing with off the field and how we were hampered financially. Our payroll dropped. We had signed players to deals based on one payroll, only to see it slashed by $20–30 million. Now we were forced to fill out the rest of the club with low-salaried players. That helped balance the budget sheet while leaving an unbalanced roster—in the second-largest market in the country, no less.

The members of the organization kept the ship afloat and moving forward while a hurricane of distractions swirled around us. We were 162-161 those two seasons—not what we wanted. We had a better record combined in those two seasons than any team in our division except the San Francisco Giants—and a record better than nine of the sixteen teams in the National League at the time. And no other organization was going through what we were going through with ownership.

Cost-efficient, homegrown talent dwindled at a time when the franchise lacked the financial resources to fill holes from the outside. We had basically abandoned international scouting and signing players in Latin America for financial reasons and it was taking its toll.

With ownership set to change on May 1, 2012, the team began that season with a payroll of approximately $90 million. By comparison, between 2013 and 2017, the Dodgers total payroll exceeded more than $1.3 billion during those five seasons. The organization also paid more than $113 million in CBA-required competitive balance tax, in addition to the payroll costs. (Clubs that exceed a predetermined payroll threshold are subject to a Competitive Balance Tax, which is commonly referred to as a “luxury tax.” Those who carry payrolls above that threshold are taxed on each dollar above the threshold, with the tax rate increasing based on the number of consecutive years a club has exceeded the threshold.)

Each day brought more bad news, courtesy of the press, which had a field day with all low-hanging fruit. We just needed to hang on and do whatever we could to have a positive effect on the few things we could control. That was the greatest lesson learned in those days—spend your energy on what you could affect in a positive manner; tune out the noise, and ignore what you had no chance to change.

As emotionally draining as those two and a half years were for all of us, no one survived them better than Frank. Sure, he was a villain to the fans and Selig. But in the end, he came out the financial winner. He paid Jamie off with a $131 million tax-free divorce settlement plus property. Then he won an important, unprecedented, and staggering concession from the commissioner. For whatever powerful reasons, Selig agreed to let Frank hold an auction among MLB-approved bidders and sell the team to the group of his choosing. He broke the oligarchy that is Major League Baseball.

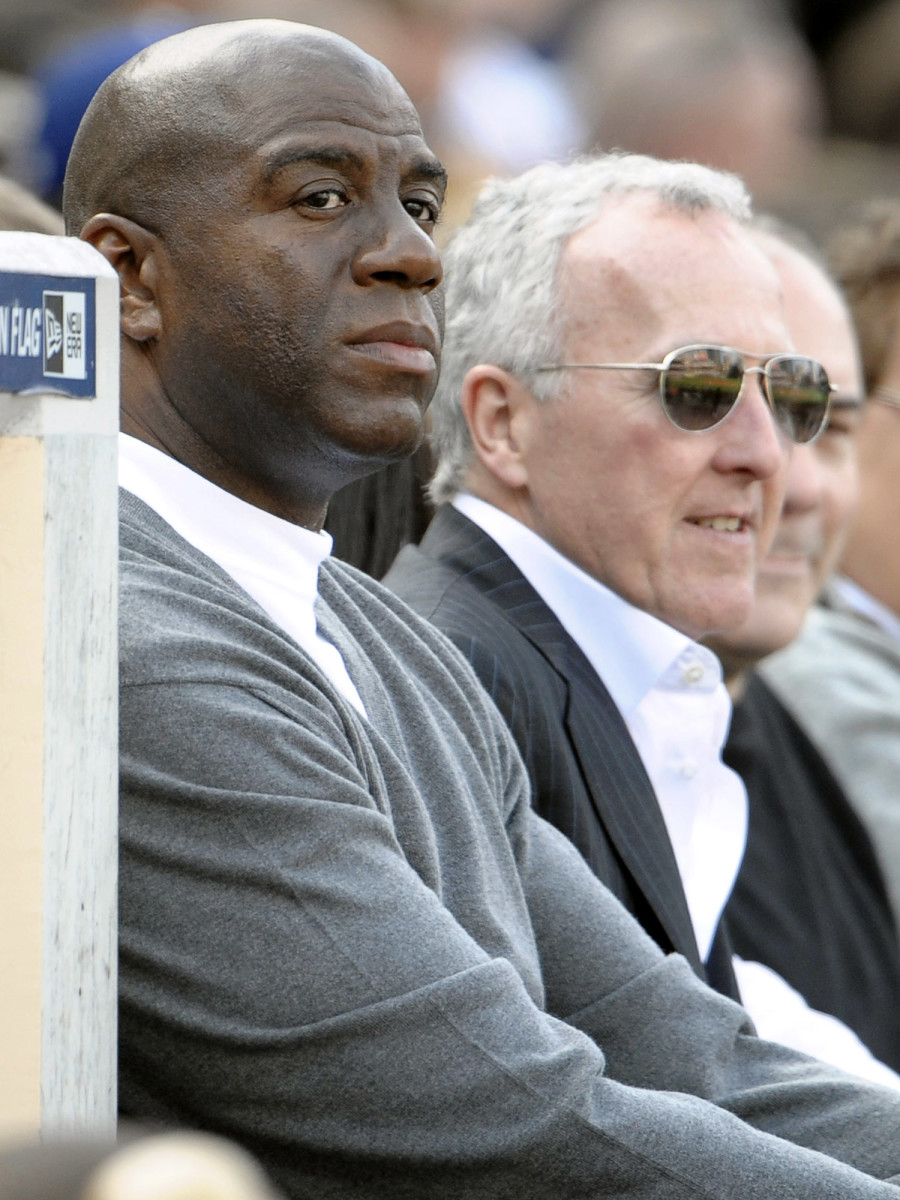

The group Frank eventually chose was headed by Mark Walter, with Los Angeles basketball legend Earvin “Magic” Johnson and four others—investors Todd Boehly and Bobby Patton, Hollywood executive Peter Guber, and longtime sports executive Stan Kasten. Doing business as Guggenheim Baseball Management, the new owners paid $2.15 billion for the franchise, parking, and real estate around Dodger Stadium. The sale price was a record for a U.S. sports franchise, far surpassing the previous high of $1.1 billion, which New York real estate mogul Stephen Ross had paid for the Miami Dolphins in 2009.

Pundits had predicted that the most Frank could get for the franchise was $1.5 billion. And few thought he would come close to that. Not only did Frank blow the doors off those numbers, but, according to media reports, he also got Guggenheim to agree to let him keep 130 acres around Dodger Stadium and to invest $400 million with McCourt Partners—a joint-venture real estate development corporation he formed with his sons and Guggenheim. For good measure, Guggenheim paid him $5.5 million the first year to manage the joint venture.

Think about that. And then remember, his attorney said the team was purchased with “not a penny” of the McCourts’ own money. Love him or leave him, the bottom-line results were staggeringly impressive.

McVillain? McBankrupt? McBrilliant.