Bob Gibson's Actions Spoke Louder Than Words in 1967 World Series

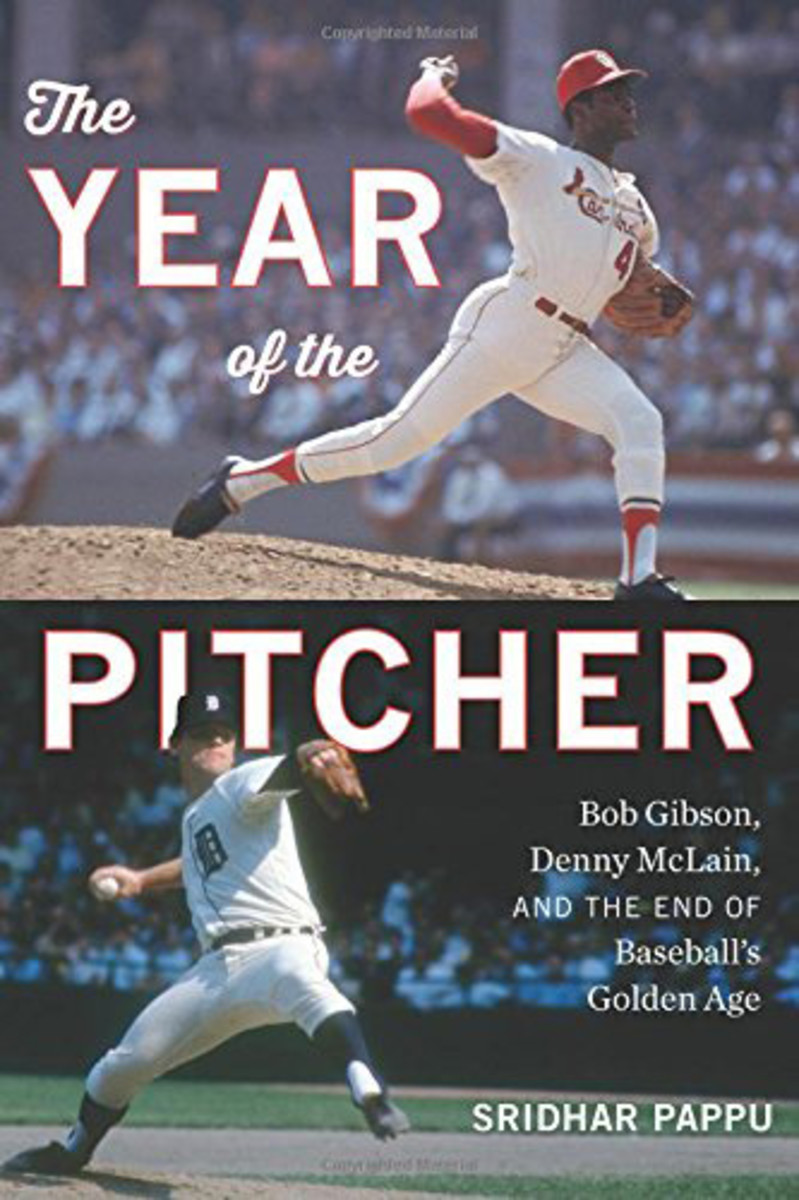

The following is excerpted from The Year of the Pitcher by Sridhar Pappu. Copyright © 2017 by Sridhar Pappu. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing. All rights reserved.

In late September, Jackie Robinson returned to Buffalo to address a meeting of the city’s chamber of commerce. This audience—consisting of well-heeled businessmen—was arguably more on his wavelength than the angry young crowd he’d met with at the YMCA that summer.

But whatever they’d asked him to speak about that day—urban renewal, unemployment among the city’s black youth—invariably fell away as discussion turned to the game he’d left behind more than a decade earlier. He was still a baseball icon, after all, and the audience wanted to hear from that man, not the public servant. The last truly great pennant race was in its final stretch, and of course someone asked him for his thoughts.

Who won was of no concern to him, Robinson said, but he hoped the Red Sox would fall short. The team’s owner, Tom Yawkey, Robinson said, “is one of the most bigoted guys in organized baseball.”

Word got out. Upon hearing about Robinson’s comments, an outraged Massachusetts-based Rockefeller supporter called on Alton Marshall, a member of the governor’s inner circle, to lean on Robinson to retract his words. But not only did Robinson refuse to take back what he said, but he promised to repeat it all over again if asked.

“I am sorry but in my opinion Yawkey is one of the worst bigots in Baseball,” Robinson wrote. “I do not go around saying things for the sake of saying them . . . I once tried out for the Red Sox and was rejected. I was informed that Yawkey would not hire Negroes regardless. His record indeed proves what I said to be true.”

Even in 1967, more than two decades after that “tryout,” the humiliation of his experience with the Red Sox still gnawed at Robinson. He’d been sent to Boston to try out at Fenway Park with the grumbling Red Sox, who had consented to hold a tryout for black players only after being repeatedly pestered by sportswriters like Wendell Smith of the African American Pittsburgh-Courier and the Boston Record’s Dave Egan. Adding his voice to the chorus was the Jewish Boston politician Isadore “Izzy” Muchnick, who believed that the bold move of desegregating the game “should begin in Boston, where abolition was born.”

The Year of the Pitcher

by Sridhar Pappu

The story of the remarkable 1968 baseball season, which culminated in one of the greatest World Series contests ever, with the Detroit Tigers coming back from a 3–1 deficit to beat the Cardinals in Game Seven of the World Series.

It was Muchnick who put pressure on Eddie Collins, the Hall of Fame second baseman who had become the team’s vice president and general manager, until he finally gave in. But when Robinson and two other black players arrived at Fenway Park to take part in something that had all the looks of a real tryout, it was anything but. The three hit against minor league pitchers and showed what they needed to in the field. Someone took notes on index cards. Collins promised that he’d be in touch. But it was clear to Robinson from the outset that it was all a charade. The Boston Braves had opened up their ranks to black players in 1950, but the Red Sox, given the chance to sign not only Robinson but later Willie Mays, would inexplicably wait.

Writing in his column in the New York Post with William Branch in May 1959, Robinson took aim at Yawkey and the Red Sox. At that moment, the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination was looking to take action against the last team in the National and American Leagues to field a black player. Addressing the charge that the Red Sox were guilty of racial discrimination, Robinson wrote: “Truth speaks for itself, and there has never been any question in my mind that the Red Sox management is prejudiced. I can’t in the least tell you why, since the Red Sox themselves are the ones hurt most by limiting their choice of players on the basis of skin coloring rather than ball-playing.”

By 1967, of course, black players had been signed by the Red Sox organization. But Yawkey was still in charge, and there remained an indelible whiteness to the Red Sox and the city they played for. Perhaps no one felt this more keenly than the Boston Celtics, who, from the arrival of Red Auerbach in 1950, showcased black players like no other team in the NBA. Bill Russell was a player-coach for the Celtics at the time, but like his teammates, he felt estranged from his city even as Boston fans pulled for the first team in the history of the NBA to start five black players.

To even these championship players, the city remained closed off and racist in its dealings. Sam Jones, who enjoyed a Hall of Fame career with the Celtics from 1957 to 1969, might be welcomed to Boston nightclubs if Sammy Davis Jr. or Johnny Mathis was playing. But Jones liked Sinatra, and to see the Chairman live he had to face unwelcoming stares, if not intimidation.

Moreover, the Celtics were taken for granted. The city had grown used to their championship banners, expecting a new one at the end of each season. Thus, in a city that had gone generations without a baseball pennant—much less a true championship—the Red Sox victory over the Twins at Fenway Park on that last day of the regular season, putting them in a tie for the American League pennant, set up a frenzied scene that very few had seen the likes of. With the final out, thousands of fans descended onto the field, many seeking out pitcher Jim Lonborg. Hoisting him high above their heads, they tore his uniform to shreds before policemen helped him to the safety of the Red Sox clubhouse. Outside, fans continued the mayhem. Signs fell. Firecrackers went off. Grown men climbed the screen behind home plate. Although this was chaos in triumph—unlike what would follow hours later in Detroit—it was chaos all the same.

From their own clubhouse, more than 900 miles way in Atlanta, the Cardinals solemnly watched this spectacle unfold on television, having settled their affairs in Philadelphia long before. Gibson and his teammates had wanted the Twins to prevail. Now they rooted for the Tigers to win that last game, to secure, at the very least, a Detroit-Boston playoff. The reason was quite simple. At a time when players’ World Series checks were calculated based on overall attendance, Fenway’s intimate size meant drastically diminished returns.

Yet, late the next day, there they were—pulling into their lodgings at the Quincy Motor Inn on the outskirts of Boston. Reportedly no hotel in Boston proper would take in the team, citing lack of accommodations for the Cardinals’ “large entourage.” They were met by hundreds of Sox fans chanting, “Welcome No. 2!” Gibson, decked out in a smart suit and thin tie, simply held up one finger on his way to his room—where the temperature was set at a not-very-welcoming 80 degrees.

There, holding court with Boston reporters, he grew increasingly agitated. A reporter handed him a paper showing a headline with Carl Yastrzemski’s prediction that the Red Sox would take the Series in six. At seeing this, Gibson only said, “Huh,” before dropping the paper to the floor.

“What’s the matter?” someone said. “You worried about Yaz?”

“I don’t fear anybody,” Gibson said. After his wife Charlene tried to cool his temper, Gibson went on to tell the assembled press, “I mean it. You guys asked for two minutes. I gotta unpack.”

When the Cardinals went to Boston for the 1967 Series, Gibson was still a man seeking to define his own place in the game. He was not yet seen as the equal of Koufax or even Marichal. He had much to prove in this Series. The cockiness that he perceived in the Red Sox, and especially in Boston fans, only fueled the flames.

Those looking at the front page of the Boston Globe would have seen news capturing the fast-changing future of the Republic. Montana senator Stuart Symington, a onetime hawk, had called for an all-out end to military action in Vietnam. A former Ohio state representative, Carl B. Stokes, had beaten a two-term incumbent mayor of Cleveland in the Democratic primary in his bid to be the first black man to lead a major city. But dominating the front page was Bob Gibson, standing alongside Boston pitcher José Santiago in a posed photograph above the fold. Santiago, for his part, looks nervous—his roundish face peers down at the baseball he’s holding. Gibson, standing next to him with his hands at his hips, wears a wide red collar beneath his buttoned-down jersey and is smiling wryly. The Red Sox had beaten the very best the American League had to offer. Now they’d have to face him.

That afternoon, when Tim McCarver walked out onto the field at Fenway before the start of the game, he shared Gibson’s confidence. Fenway still lacked a darkened batter’s eye, and McCarver believed that the white shirts on fans in the center-field bleachers would give Gibson the advantage. Gibson had proven himself unhittable at times with a black background behind him. How could he fail to make an impact at a venue where the hitters would be half-blind?

Jim Lonborg admitted that the tense last weeks of the Red Sox season had kept the team from spending much time thinking about who they’d play next. They were just hoping to survive the pennant race, which, until that Sunday, had been very much in doubt. What they knew of the Cardinals came from scouting reports, hastily compiled in September.

They knew, of course, about Lou Brock, whose spectacular hitting and tenacious base running had broken the will of so many teams in his own league. In Game 1, he opened with a single in the third inning and would score the first run. In the seventh, with the game tied 1–1, he singled again, stole second, and scored again—helping Gibson seal a 2–1 win.

Lonborg, however, was more worried about Gibson. The Red Sox knew about his reputation as an intimidating, aggressive pitcher. They knew that he’d broken his leg midseason, so they expected that, with the forced respite from the wear of the regular campaign, he’d be coming back “pretty fresh and strong.”

After watching him in the first game, Lonborg believed that he’d seen one of the most terrifying and intimidating pitchers he’d ever seen. Gibson was just that good. Lonborg and his teammates remained confident in themselves and their bats, but they knew that getting to Gibson early remained key. To fall behind was to stay behind.

Still, Carl Yastrzemski, for one, refused to give Gibson his due. Following Game 1, in which he went hitless, Yaz stood on the field taking batting practice.

“I don’t like a couple of days off,” he said. “I don’t feel right at the plate. My six-year-old son could have got me out.

“Gibson threw hard,” he continued, “but we’ve got pitchers in our league who throw hard too . . . The greatest asset Gibson had was his ability to move the ball around. I can’t wait to face him again. I feel great now. I wish we were playing a doubleheader Thursday. But in this game, I had slow hands. I didn’t swing the bat the way I should.”

Following that first effort against the Cardinals, Boston’s survival seemed very much in doubt. The pressure was on Jim Lonborg—who, until that season, had shown only flashes of promise—to keep the Sox in the Series, to be their Bob Gibson.

It was a tall order. Gibson’s ability to manhandle hitters through both technical prowess and intelligent intimidation was unmatched. In fact, the two pitchers couldn’t have been more different in how they handled themselves both on and off the field.

From the time he came to the Sox, Lonborg had earned the nickname “Gentleman Jim.” A tall, dreamy-looking bachelor with an easy temperament and a degree in biology from Stanford, he at one point contemplated walking away from baseball and becoming a doctor. (In later years, he’d become a dentist.) But the Red Sox signing bonus proved too tempting for the earnest and handsome young pitcher. For their part, the team believed that Lonborg could help bring an end to the decades-long misery of being denied a championship.

His photogenic good looks seemed at times to overshadow his pitching. In an era when it was unheard of for athletes to pose in expensive suits in the pages of general interest magazines, Lonborg (who broke his leg in a skiing accident following his Cy Young season) appeared in a 1968 photo spread projecting an image of unflappable cool. One photograph shows him in a blazer and checkered slacks at an Eastern Airlines counter, a stewardess gazing longingly at him. In another, he’s wearing a plaid sport coat and gold pants while chatting with a pretty companion. The photos seem less like staged photographs than scenes plucked from real life. It was certainly easy then to imagine him stepping off the pitching mound and into a scene with Mia Farrow or Ann-Margret, holding his own with the starlets of his day.

Nor did it hurt his stock that even when struggling to find his form early in his major league career, Lonborg always maintained friendly relations with the Boston press. Unlike Gibson, who sidestepped reporters, Lonborg was always amiable. Sportswriters had their jobs, and he had his. He understood how they needed each other. Moreover, he liked them.

Yet it wasn’t until Lonborg understood what it meant to be mean, at least on the mound, that he made the transition from pressman’s favorite to an ace. Many, including manager Dick Williams, attributed this change to an early season loss to the Angels in Anaheim. Holding a 1–0 lead into the bottom of the ninth, Lonborg gave up two singles and let California tie the game. Looking around, he saw two men on, with two outs. He’d let the hitters dive over the plate, taking ownership of the space that was rightfully his. When he threw a wild pitch to score the winning run, he left the field wondering what might have happened had he not let the hitters position themselves as they did. He decided from that point forward never “to give a batter a break.”

Williams believed that Lonborg had turned the corner with that game, that he’d needed a “jolt” to understand that baseball had a toughness to it, however genteel a sport it might appear to be. A pitcher had to develop meanness to win, whether it expressed his true nature or not.

Over the course of the next nine games, under the tutelage of Sal Maglie, he would throw at and hit six different batters. By 1967, Maglie, who helped Gibson and Don Drysdale as a teammate, had become a pitching coach, and throughout that summer he taught Lonborg what those two already knew: that success depended on establishing himself on the outside part of the plate. To achieve this, he’d have to keep hitters on the inside part, always aware that should they lean in or lunge at pitches on the outside, the consequences would be painful.

However, it was Sandy Koufax, now in the early stages of a short-lived and ill-advised television career, who approached Lonborg near the batting cage before Game 2 with words that would change his life. The reserved left-hander asked Lonborg how he prepared for a game in the bullpen, what he did to warm up. Lonborg told him that he just threw fastballs and curveballs until he felt ready to come in. Koufax said he needed to do more.

“Have you ever thought about putting their lineup as imaginary hitters at the plate when you are warming up?” Koufax asked. “So that, when you come out on the field and actually play the game, you psychologically have visualized getting all of these hitters out?”

This advice stayed with Lonborg for the rest of his playing career. And while one could argue about its immediate impact on Lonborg’s pitching, the fact was that his performance that day was Gibson-like. Lonborg stuck to what Maglie had taught him, never giving Brock or any other Cardinal hitters the opportunity to extend their arms. During his 5–0 shutout in Game 2, he retired the first 19 consecutive batters before giving up a walk in the seventh and allowing just one hit—a double in the eighth. Nelson Briles, however, won Game 3 for the Cardinals, 5–2, and Gibson won Game 4 to put St. Louis within one game of winning the Series at home. But Lonborg matched him the following day, allowing just three hits and one run, in the bottom of the ninth, to bring the Red Sox a 3–1 victory in Game 5.

While the Red Sox focused on Brock, Lonborg believed he had an advantage against the right-handed-heavy Cardinals lineup. They were high-ball hitters whom Lonborg knew he could challenge if he kept command of his pitches in the lower part of the strike zone. In his first two Series starts, he had not only that control but an awareness of what he was trying to do. He would later call those games the kind of “perfect moments” that seldom come.

Through six games, he and Gibson circled each other like prizefighters. Having staved off elimination once again in Game 6 behind right-hander John Wyatt, the Red Sox would have a chance to win their title at Fenway Park. In Game 7, Gibson would pitch for the third time in the Series, on three days’ rest. Williams would call upon Lonborg once more, after just two days.

Gibson had “honestly” felt that the Cardinals would do him a favor and win the Series before he had to pitch again. Instead, he would be facing his second Game 7, and his sixth World Series start. Of course he could have used more rest. But he’d been here before. There was something about these games that gave him a “little extra.”

“What do you want me to do? Be excited?” he said. “I’m not. I’m not trying to prove anything. I just want to win it.”

That same evening, when Boston Globe writer Will McDonough visited Lonborg at his apartment, he found that the Red Sox pitcher didn’t share Gibson’s outlook. Lonborg was staring at a large photo of the moon that he’d hung in his living room. He admitted that, after winning the American League pennant, he didn’t think he’d ever experience anything as thrilling again.

“But I was wrong,” he said. “Pitching the seventh game of the World Series will be greater.”

The apartment’s hallway was crowded with paper bags filled with letters and postcards, notes from well-wishers thanking him for what he had accomplished. Anything seemed possible now. The once-unfathomable championship was suddenly within reach.

“I’m not going to kid myself about it,” Lonborg said. “I’m not going to be as strong as I’d like to. But I’m just going to give it everything I have. Why save it? There’s nothing after tomorrow.”

At the park the following day, Lonborg sensed early on that he wouldn’t be the same pitcher he’d been in the first two starts of the Series. Still, he hoped that he’d be able to locate the ball with greater precision, to force the Cardinals hitters to swing at pitches they’d normally lay off of. And he desperately wished that his teammates could accomplish what they hadn’t been able to in Games 1 and 4—score early, forcing the Cardinals ace from the game.

Lonborg had hoped for two things: that his teammates could get to Gibson early and that, working on two days’ rest, he’d have a cushion to work from. Neither happened. In fact, things quickly got out of hand when Dal Maxvill—the wiry shortstop with little power—hit a triple in the third inning, staking the Cardinals to a 2–0 lead. When Gibson came up to bat in the fifth, he blasted a home run that hit the ledge of the left-center-field wall. None of what Lonborg had banked on—an early lead, undisciplined hitting from the Cardinals—came to pass. The Cardinals won the game going away, 7–2. Boston’s “Impossible Dream” was over.

Gibson would later admit that he too had worried about how much he’d have in reserve after only three days’ rest. He could pitch six innings, he was sure of that. As the game progressed, his body and his arm grew more tired with each pitch. But unlike Lonborg, he had the early runs to work with. After the eighth, with a large lead and his stuff diminishing, he didn’t think he could finish. But he managed to cobble together whatever was left to complete his third complete-game win of the Series.

It had been a storied day that began less than auspiciously. That morning Gibson and his wife joined the McCarvers and the Maxvills for breakfast in Quincy. While everyone else was served, Gibson’s breakfast of scrambled eggs and toast, for whatever reason, never arrived. The story would go through several iterations, but the bottom line was that Gibson boarded the Cardinals’ bus to Fenway with an empty stomach and a toothache to boot. It was Post-Dispatch columnist Bob Broeg who would jump off the Cardinals’ bus to hunt down a couple of egg sandwiches for Gibson.

Born and bred in St. Louis, Broeg had followed the Cardinals since birth. He was every bit the company man, cultivating close relationships with Musial and Schoendienst. But like Gibson, he was hot-tempered and quick to throw whatever was at hand whenever the University of Missouri Tigers or any of the other teams he followed fell behind.

To future Post-Dispatch columnist Rick Hummel, this shared temperament made them ideal for one another. Broeg, Hummel felt, was never afraid to challenge Gibson when he grew sullen. He fought back. Hummel surmised that each appreciated the tenacity in the other; perhaps that was what endeared them to each other well beyond Gibson’s playing days.

Boston writers couldn’t say the same. Perhaps they mistook Gibson’s confidence for indifference, his aloofness for anger. Bob Sales of the Boston Globe wrote that Gibson was “blasé about his job. He does not show the enthusiasm for his work that some of his cohorts do. It is in his makeup.”

Of course, nothing could rattle Bob Gibson. One comment, though, in particular worked on him: the words in a Boston paper announcing Dick Williams’s plans for the seventh game—“Lonborg and Champagne.” Watching Gibson studying those words, his teammate Joe Hoerner knew how much they would fortify Gibson’s resolve. It wasn’t that he needed any extra motivation to win his fifth consecutive World Series game, but that smug headline, combined with the perceived slight at breakfast, would bolster Gibson’s belief that he needed to prove to the world that he was capable of anything.

In Game 7, Gibson allowed only two runs with three hits, striking out 10 and winning the World Series MVP once again. As Williams walked to the visitors’ clubhouse to offer his congratulations, he could hear his own words being mocked—“Lonborg and Champagne! Hey!” Then Williams saw what millions at home were seeing on television—Cardinal players chanting in unison, stomping their feet, spraying each other with champagne.

Gibson sat off to the side—drinking, not spilling, champagne. The night before, he’d gone to hear Les McCann play jazz piano. Now McCann entered the locker room, his fist raised, yelling, “Black Power!” Gibson had little use for such sentiments—his power was his, and his alone—but he’d showed them what Jackie Robinson and Willie Mays and scores of Negro players could have accomplished had they teamed up with Johnny Pesky and Ted Williams. Gibson may have been reticent about speaking out on social issues, but his actions spoke louder than his silence—a black man could win in Boston.