The Big Papi Show: Inside David Ortiz's Transition from Red Sox Hero to World Series Analyst

David Ortiz dropped the most beloved public F-bomb of all time, so he is clearly a gifted orator. Still, the king of the postseason walk-off found himself feeling something he wasn’t accustomed to after Fox Sports hired him to sit in the center chair behind its pre- and post-game desk for this year’s baseball playoffs: nerves. Galvanizing his traumatized home town was one thing. “This is our f------ city!” he told Fenway Park on April 20, 2013, five days after the Boston Marathon bombings, drawing praise from even the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission. Formulating coherent and analytical—and, ideally, non-profane—soundbites in front of 19 million viewers, in his second language, was an entirely new challenge.

His broadcasting career got off to an inauspicious start. “I’m lost, man! I’m lost!” he shouted on his first day of work as he wandered near the loading docks of Fox’s expansive studios in Los Angeles, until Bardia Shah-Rais, Fox Sports’s coordinating producer, found him. Things quickly improved. “We told him, ‘Be yourself,’” says Shah-Rais. “’Don’t be a broadcaster. Don’t look into the camera and try to make a fifteen second point.’ I think people like his delivery because it’s real. He’s not trying to be Anderson Cooper or Brian Williams or Lester Holt.”

“I don’t try to be Mr. Perfect,” Ortiz says. “I just try to talk about what I know in the way I know how.”

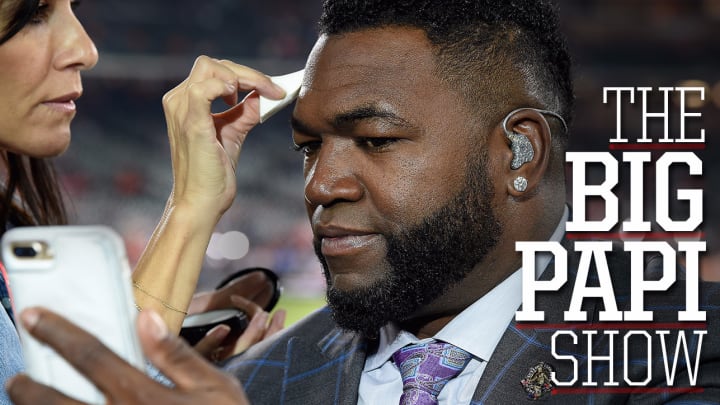

It’s led to a range of memorable moments, such as his insightful dissection during the ALCS of CC Sabathia’s pitching repertoire (he explained, bat in hand and from experience, why Sabathia’s alternating between a backdoor slider and a cutter flummoxes hitters) and a portrait he drew in honor of one of Justin Verlander’s playoff outings that included a performance-summarizing inscription on which, the producers and many viewers initially thought, the FCC might not look as kindly. “What are you doing?” Shah-Rais shouted to Ortiz through his in-ear IFBs – which were not yet the diamond encrusted pair, inspired by the singer Romeo Santos, that he would break out for the World Series. “What’s the matter with you? You can’t write ‘S---’ on the card!”

The Astros and Dodgers Have Forever Changed Baseball With an Unforgettable World Series

“What, are you an idiot?” Ortiz responded. “It says 5 HIT!”

By then Ortiz—known to everyone at Fox, as everywhere else, as Big Papi—had become as settled in on the desk as he once was in the batter’s box. He credits the show’s host, Kevin Burkhardt, and his fellow panelists Keith Hernandez and Frank Thomas with making him comfortable. His greatest tutor, though, has been the person even he might have expected to be the least likely candidate.

****

“What’s up, ladies! It’s gonna be a great day, great day, great day!” Alex Rodriguez calls out to the hair, makeup and wardrobe department as he sweeps into Fox’s production trailer, parked just beyond Dodger Stadium’s centerfield fence, five hours before Game 2 of the World Series on Oct. 25. The collar of his ironed golf shirt is popped, his hair is gelled and his teeth are very white. Fox researcher Anthony Masterson passes Rodriguez a thick packet of notes and stats as he walks by—a practiced handoff, by now.

Rodriguez had a head start on Ortiz in the TV world. Improbably, it turns out that his polished and studied manner, which often played terribly in clubhouses—particularly opposing ones—has made him a star in the medium, with an approval rating he never approached on the diamond. Though he took his last major league at-bat only 14 months ago, in addition to his Fox gig he is already, among other things, a guest judge on Shark Tank—he and Mark Cuban recently invested in the Ice Shaker, a product from Rob Gronkowski and his many hard-partying brothers—and even a contributor to ABC News.

Fox executives, though, had some concerns when batting around the idea of bringing in Ortiz to replace Pete Rose, who had formed a compulsively watchable odd couple with Rodriguez last fall but was fired in August amid allegations that he had once had a sexual relationship with a minor. The central issue was the presence of Rodriguez, his longtime antagonist from their days with the Yankees (in Rodriguez’s case) and Red Sox (in Ortiz’s). Fox felt that their mutual antipathy might not have stayed between the lines. “The one rub is, how do these two get along?” Shah-Rais wondered.

But Rodriguez was unequivocal. “You bring him in here,” he said. “and I got him.”

In Rodriguez’s telling, he and Ortiz have been pals for two decades. “An unbelievable relationship, for a really, really long time,” as he puts it. The origin story Rodriguez unspools begins in 1996, when both were 20 years old and members of the Mariners’ organization—Ortiz in Single-A, Rodriguez with the big club. It includes a rained-out exhibition game between Rodriguez’s Mariners and Ortiz’s Wisconsin Timber Rattlers, which turned into an impromptu home run derby, which Ortiz won. “He took out Jay Buhner, Edgar Martinez, Ken Griffey Jr. and myself,” says Rodriguez. “Really, that was the first birth of Big Papi,” even though Ortiz was still seven years and two organizations from becoming a household name.

Ranking the Craziest World Series Games Ever After Dodgers-Astros Game 5

Rodriguez mostly elides over what happened next, when they found themselves on opposite sides of baseball’s most heated, and often most genuinely nasty, rivalry. “When you’re trying to play for the pennant, emotions are high,” says Rodriguez. “If you talk about any dislike, and I don’t think that’s the word, it was less than one percent of a twenty year relationship.”

Ortiz fills in the gap. “Sometimes one of the things that people hate is you being the best at something,” he says. “On top of it, people believed that the way A-Rod handled himself wasn’t the right way, I can tell you that. Players always expect you to be humble, to be agreeable. Yes, I know A-Rod from way back there. At some point, things got kinda weird.”

“Sometimes we need to crash into something, so we learn something,” Ortiz continues, of the years in which Rodriguez, once a golden boy, emerged as the league’s preeminent heel. “I’m not saying that Alex was a bad person or anything. Sometimes momentum forces you to carry yourself differently, without even knowing what you’re doing. I don’t know if that’s his case or not. But the A-Rod I see now is a more approachable guy.

"I really like the A-Rod that I’ve been dealing with these past three weeks. You know what? I even make the comment to him at some point: Did J. Lo have something to do with this?” Rodriguez has been dating the actress and singer Jennifer Lopez for at least six months.

For his part, Rodriguez says he’s always admired Ortiz’s charisma and magnetism—not without envy. “I’ve called him the Magic Johnson of our game for over a decade,” he says. “He’s the one guy that crosses over. He’s the one guy that everyone loves. He appeals to the masses. It was fascinating. He broke our hearts so many damn times. But even Yankee fans like Big Papi. I’m like, how the f--- is that possible?”

Now it is Ortiz who marvels at Rodriguez, for his quick post-baseball transition to budding mogul. His broadcasting is only one of his many ventures, and Ortiz wants to follow Rodriguez’s lead. Ortiz’s longtime manager, Alex Radetsky, lists his client’s activities during the past year: “Endorsement deals. Production days. Appearances. One-off events. Business initiatives. Production companies. Wine line.”

“I love the way that A-Rod does things,” Ortiz says. “He’s a guy that works extremely hard at what he does. I have learned so much from him. To me, that’s my goal, to be able to get to his level. He’s been doing this for a while, and he’s extremely smart. The way he’s handling himself? I would call it perfect.”

On air, Rodriguez has subjected Ortiz to only good-natured hazing. In fact, he spends much of his time putting him in position to succeed – teeing up a point for him, then allowing him to connect with it.

“Papi,” he might say. “Why is Verlander so hard to hit? Tell me about it.”

“I’m the rookie in there,” Ortiz says. “That makes my job easier. He’s always touching the toughest bases about the subject, and he’s passing it to me already constructed.”

It’s not only for the cameras, either. During commercial breaks, Shah-Rais will often hear a conversation conducted in Spanish over his headset. The first time it happened, he thought his feed had become scrambled – until he realized that it was Rodriguez, coaching his new partner. “What you said in the meeting was interesting,” Rodriguez will tell Ortiz. “Why don’t you do that here?”

“Remember,” Rodriguez will say. “Just be yourself.”

****

For Ortiz, the secret to the universal popularity that evaded Rodriguez for so long is simple: he is always who he is, no matter what.

“I think it’s not easy to connect with people,” he says. “Since I’m very sincere, and I speak from the heart every time I say something, I guess people connect with that. My dad always says I got that from my mom. Me being always up, being able to give interviews in front of the camera, on the big stage, stuff like that. Not everyone can be like that.” Ortiz’s mother, Angela Rosa Arias, died in a car crash in their native Dominican Republic in January of 2002. Each time he pointed both index fingers to the sky after a home run, he was pointing to her.

In a sense, Ortiz’s openness made him an ideal replacement for Rose, who also came across as real, although in a different, more rumpled way. Ortiz is an equally good counterpoint to Rodriguez, who even in his post-career renaissance still never quite seems to be entirely genuine, although it is certainly possible that Alex Rodriguez has been playing the role of Alex Rodriguez for so long that it has become indistinguishable from his true identity.

Rodriguez really is a baseball nerd and likes to show it, often drawing upon the finely sliced stats that Masterson has given him as well as his own deep knowledge of the game’s history. Ortiz tends to speak from his own experience. “One of my friends called me and told me that he had watched the show with his son,” Ortiz says. “His son, who’s sixteen, said, ‘Daddy, I like how David talks about the player from this era, the players I know. I don’t know those players that A-Rod mentions sometimes. Like, Lou Brock?’

“I would say you need to find a way to talk to these millennials,” Ortiz says. Even Big Papi is not above occasional marketing speak.

****

For a long SUV ride through LA traffic from his luxury hotel in Beverly Hills to Dodger Stadium before Game 2, Ortiz is dressed in a black t-shirt embroidered with a massive bejeweled skull that covers his considerable torso, complemented by a much tinier skull that is affixed to the bridge of his sunglasses. Someone in the SUV asserts that some people are always their true selves, and it turns out that others still don’t like them—at least, not nearly as much as they like Ortiz. That concept doesn’t seem to compute for him. Authenticity, for Ortiz, is all there is.

That was why he still doesn’t understand why nobody believed that he was actually going to retire from the Red Sox last year, as he always maintained, and—with a $17.2 million option for 2017 waiting for him—that he wouldn’t return.

Ortiz, though, had been honest about the pain that he experienced toward the conclusion of his career, which ended last October, when he was 40. He says that he played through a partially torn Achilles tendon for his final five years. Eventually his other tendon became partially torn, too. He needed four hours of treatment before games and one hour after them just to be able to play designated hitter. Playing first base became out of the question.

“My last year, I was here at Dodger Stadium,” he says. “In the fifth inning I told the manager, Hey, get me out of the game. I chased a ball playing defense, and my Achilles tightened up on me real bad. It was time to go, man. My body was just like, I’m done with this.”

Historic World Series Home Run Rate may be Result of Slicker Baseballs

Even so, he says, “To be honest with you, I don’t miss playing baseball. I’m the kind of person who accepts things easier than I would say some other people do, you know what I’m saying? Most of us, we get out of the game because it’s somebody else’s decision. Whenever you get out of the game because it’s somebody else’s decision, in your mind you feel like you could still play. I could have played another year if I wanted to. I was just in too much pain.”

Now his tendons feel better, and he stays in shape with SoulCycle. He moved his family to Miami this year, though he retains his house outside Boston, where the oldest of his four children—a daughter—attends college. Florida, though, offers year-round baseball, attractive to his soon-to-be 14-year-old son. “He’s developing really good, so I want to be around the next couple of years to see how much I can help him,” Ortiz says.

There’s another reason he moved. It’s hard being a city’s hero, especially one who rarely says no to anybody. “In Boston, man, I have no private life over there. I don’t blame people, but you know what I’m saying? Miami is a little slower.”

The 43-year-old Burkhardt—whose persona also seems identical off-screen and on, that of your best buddy from back home in Jersey, except with monogrammed dress shirts and great hair—has spent just three weeks with Ortiz, but he can already see what the Red Sox are missing. “They had plenty of talent, but when you’re around him—the stuff he does, how he acts—it’s like, Oh my god, I’d love to play with this,” Burkhardt says. “He takes every bit of pressure off. He’s motivating. He gets on a point, he drives it home, he’s passionate, he laughs.”

Many of the laughs the cast has shared this month, on screen and off, have stemmed from the rivalry between the Yankees and the Red Sox—and most of them have been initiated by Rodriguez. While the Yankees were still alive, and particularly after the Red Sox had been eliminated by the Astros in the ALDS, Rodriguez loved to brandish his World Series ring in the direction of Ortiz, even though Ortiz owns three times as many. In a backstage prank that became a viral video, Rodriguez attempted to drape a Yankees jacket around the shoulders of his unsuspecting panel mate, who reacted appropriately.

“That was real,” Ortiz says. “I was talking on the phone to my dad about some subject. I thought someone was putting a blanket on me or something—it’s cold in the studio. Until I saw the NY on my shoulder. I was like, ‘Oh s---! Hell no, I ain’t wearing that jacket.’ A-Rod, he used to be the straight-faced kind of a guy. Now he’s having fun.”

Of course, there seems to be something calculated about Rodriguez’s extremely public assertion of his allegiance to his old club. His 12-year tenure with the team was never nearly as warm as Ortiz’s with the Red Sox, and was often outright fraught. In 2013, Yankees G.M. Brian Cashman publicly commanded him to “shut the f--- up” after Rodriguez, already embroiled in a performance enhancing drugs controversy, announced on Twitter that he’d been medically cleared to return from a torn labrum in his hip—and this was before the league officially suspended him for the entire 2014 season. In August 2016, the club essentially forcibly retired him. Still, Rodriguez has made it clear that wants to be known as a Yankee forever.

“I love it,” says Cashman. “There was that temporary horrible time that we were all dealing with. But for the most part the relationship was really good. He performed at a high level. He was impactful in our clubhouse. He’s an exceptional baseball mind. Great personality that you see playing out now on TV. Even when he walked through that fire that we all had to walk through, when the dust settled he swung back around and made amends. There’s forgiveness and acceptance, for the most part, for most parties.”

Ortiz’s view, naturally, is less equivocal. “Things didn’t end up the way things should be,” he says of Rodriguez’s departure from the Yankees. “To be honest with you, there’s a problem between that organization and its players, I believe. I don’t even think Jeter is happy with them, you know what I’m saying? Now you would be like, hold on, Derek Jeter is not happy with the Yankees? What’s going on. Somebody needs to figure out what’s going on. I’ve been thinking: Wait a minute, how come the legends are not happy once they get out of town? I don’t know. But I’m happy with the Red Sox. I’ll tell you that.”

His other opinions are less potentially controversial, such as his approval of the choice of Astros bench coach Alex Cora to replace John Farrell as the Red Sox manager. “That’s my boy,” he says. “We played together in 2007, when we won the World Series, and we always stay in touch. He’s a baseball guy. Very smart, man. He’s going to be successful there.”

He gushes even more about one of his new favorite players, Aaron Judge, even though Judge is a Yankee. “He’s like this huge teddy bear, and he’s just trying to get better at things,” Ortiz says of the rookie behemoth. “I love that type of human being. This planet, this world, needs more people with a good heart. Right now, you see a lot of people walking around angry. There’s a lot of athletes out there making a s---load of money, you look at them and they’re straight up a------- . What is the reason for that? You live through the fans. Your family, yourself, your wife, kids, you guys are who you guys are because the fans pay for it. If the fan don’t give a s--- about what we do, you don’t have a career, period. Why you gotta be an a------? I hate when we see athletes handling themselves that way. Like their s--- don’t stink. I don’t like that. So, Aaron Judge is one of those guys who is doing everything the right way. And I love that.”

It’s pointed out that Ortiz hasn’t really addressed Judge’s baseball talent. He is more concise on that topic: “Power? Aw, s---. Don’t get me wrong, I got pop when I played. But this guy’s power is just not human, to be honest with you.”

In Ortiz’s world, talent is talent, but it’s heart that matters.

****

It is around 100 degrees in Los Angeles, and as the Fox crew’s faux wood-paneled trailer fills with people for its daily pre-show meeting, the air conditioning unit can’t keep up. It’s set to 70, but reads 76 and keeps rising.

Keith Hernandez—also new to the show this year, but a seasoned broadcaster—sits on a sofa, his reading glasses perched on the end of his nose. The 64-year-old Mets great is wearing a yellow tie, knotted all the way up, but he has removed both his shoes and his socks. On the other end of the sofa, Frank Thomas, for now the only Hall of Famer in the room, has his capacious white dress shirt unbuttoned to his sternum.

Then Ortiz enters the trailer, which occasions elaborate, full body handshakes with several members of the crew. “Bardia, I gotta tell you something,” he says, after hip checking the showrunner nearly across the room.

“What is it?”

“I was sweating my balls off out there yesterday.”

“Good news!”

“What’s that?”

“It’s just as hot today!”

It’s all very jovial until the baseball talk begins, and the panelists start formulating points they will want to make on the show. “Last night was great, but I don’t think we’ll be going into the TV Museum quite yet,” says Shah-Rais. Ortiz dips out, and returns with a heaping plate of chicken and salad.

After a Game 5 for the History Books, the Astros and Dodgers Wonder About Those Slick Baseballs

“Papi, my god,” says Shah-Rais. “You going to the electric chair today?”

The topic turns to the Astros’ lineup, which during the playoffs has been less productive than the league’s top-scoring offense ought to be, particularly at its top. Since the first game of the ALCS, leadoff man George Springer has batted .088 (3-for-34) with no home runs and four walks against 11 strikeouts.

“I’d call him into the office and say, I want you to do one thing for me: drive the ball to right-center,” says Rodriguez evenly, assuming the role of Astros manager A.J. Hinch. “If you strike out, it doesn’t matter. To have to ignite the offense in front of Jose Altuve and Carlos Correa, it’s a lot of responsibility.”

Hernandez politely rejects the idea of moving Springer down the lineup. “What got you to the dance, stay with it,” he says. “But the leadoff hitter has got to set the tone.”

Ortiz has had enough. He slowly rises to his feet and walks to the center of the room. “Guys, every man in baseball is replaceable,” he says. “You try to win the f----- World Series. You do whatever you need to win the World Series. A-Rod, I remember what Joe Torre once did to Roger Clemens in the second or third inning of the ALCS. He took him out. Springer is struggling badly. He’s not even hitting his pitch. That is baseball. You gotta keep the line moving. It happened to you, it happened to everyone in baseball. Why not to him? Move him. Somewhere else. He’s not helping me as a leadoff man.”

Sweat starts to bead on his temples, and he’s nearly shouting now. “He’s trying to hit the ball out of the stadium with every swing. All right, let me hit the ball out of the stadium. Meanwhile, I need someone on base!”

All two dozen people in the room are silent. You can hear the air conditioner struggling. Everyone is thinking the same thing, which is that this must be exactly the type of speech Ortiz delivered hundreds of times, before big games, at the center of the home clubhouse in Fenway Park. It is undeniably rousing.

It is also wrong. Springer started producing that night—from the leadoff spot, where Hinch kept him—and he didn’t stop. Over the next four games, three of them Houston wins, more than half of his plate appearances would wind up with him reaching base, on four walks and seven hits, three of which were homers.

More accurate analysis will come. Ortiz is still new to this. What counted was that he said what he believed, and that he really meant it.