The Hall of Fame Is Incomplete Without Marvin Miller

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the 2018 Modern Baseball Era Committee Hall of Fame ballot, which will be voted upon by a 16-member committee of writers, executives and Hall of Fame players at the Winter Meetings in Orlando, Fla,, with the results to be announced on Dec. 10 at 6 p.m. ET. For a detailed introduction to the Modern Baseball ballot, please see here.

In the wake of the controversial 2001 election of Bill Mazeroski, the Hall of Fame began what has become a seemingly endless cycle of revamping the process by which executives, managers, umpires and long-retired players were considered for election, largely because candidates from that last category have gone missing. Setting aside the 2006 Special Committee on the Negro Leagues, just 18 men have been elected by the expanded-and-then-contracted Veterans Committee and its successors, the Era Committees. While that wasn't an unwelcome reduction from the 35 men elected by the VC from 1985 to 2001, just three of the 18 were honored for their careers as major league players, all posthumously. Even as the elections have tilted heavily towards non-players—primarily because they’re not leftovers from BBWAA elections—the candidate with the strongest case of any individual outside Cooperstown (perhaps the strongest case of any non-player in the game's history) remained on the outside looking in.

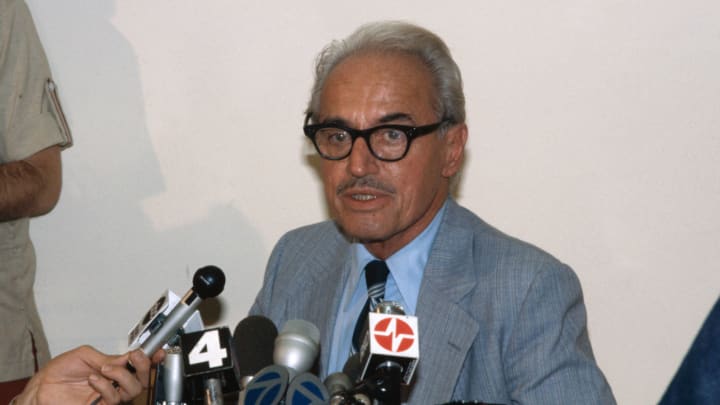

As the executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association from 1966–82, Marvin Miller oversaw the game's biggest change since integration by dismantling the reserve clause, thus shifting the century-old balance of power from the owners to the players. Miller helped the union secure a whole host of other important rights as well, from collective bargaining to salary arbitration to the use of agents in negotiations. During his tenure, the average salary of a major league player rose from $19,000 to over $240,000, and the MLBPA became the strongest labor union in the country. In 1992, former Dodgers broadcaster Red Barber called Miller one of the three most important figures in baseball history, along with Babe Ruth and Jackie Robinson.

Even so, petty politics have prevented Miller from receiving proper recognition via enshrinement in the Hall of Fame, both during his lifetime and since his death at the age of 95 in November 2012. From his retirement to the 2001 expansion of the VC, he didn't appear on a single ballot. Influential players from the pre-union days resented the high salaries and freedom of movement that modern players enjoyed, and even the most historically minded writers on the committee disagreed on his eligibility. Once Miller finally made the ballot in 2003, many of the players whose careers he helped most, such as Reggie Jackson, wouldn't return the favor. Though he eventually gained momentum in that format, when the process reverted to a small-committee one in 2008, Miller suffered the indignity of receiving just three out of 12 votes on a particularly tilted panel that elected his longtime adversary, commissioner Bowie Kuhn.

Revisiting Jack Morris's Controversial, Never-Ending Hall of Fame Debate

Understandably, Miller had had enough, and asked the Hall of Fame not to include him on another ballot via a letter sent to the BBWAA. Despite his wishes, he was considered again on the 2010 VC ballot and then the ’11 and '14 Expansion Era ballots, the latter posthumously. Prior to that vote, Miller's son Peter reiterated the family's plan to boycott the Hall of Fame induction ceremonies even if he were elected.

Now Miller is the lone non-player candidate on the 10-man Modern Baseball ballot. Does he have a chance? Unlike his last ballot appearance or even last year's Today's Game ballot (from which former commissioner Bud Selig and executive John Schuerholz were elected), there are no slam-dunk candidates from among these 10. In my analysis, both catcher Ted Simmons and shortstop Alan Trammell are worthy of election, but the panel is more likely to turn to Jack Morris based on his level of prior BBWAA support and his old-school appeal. Thus it would appear there's at least an opening for Miller's long-overdue election. Until the actual panel of voters is announced, it’s difficult to gauge his chances; past panels have been stacked with executives with long anti-union histories.

Bronx-born and Brooklyn-raised (as a Dodgers fan), Miller first walked picket lines with his parents; his father Alexander was a clothing salesman, active in the International Garment Workers Union, while his mother, Gertrude, was a member of the New York City teachers union. He graduated New York University with a degree in economics, resolved labor-management disputes for the National Labor Board during World War II, and worked for the International Association of Machinists and the United Auto Workers before joining the staff of the United Steelworkers Union in 1950. He became the steelworkers' chief economist and negotiator.

Before Miller got involved with baseball, the players were barely organized. While attempts to unionize in opposition to a salary cap and the restrictions of the reserve clause, which bound players to teams indefinitely, dated as far back as 1885, early efforts came and went. The players established an informal union in 1954, but it had no full-time employees, did not engage in collective bargaining and had just $5,400 in the bank as of 1966. At the time, the minimum major league salary was just $6,000, only $1,000 more than it had been in 1947.

In 1947, the owners had established a pension plan for players, one whose scheduled expiration in 1967 set the wheels in motion for Miller’s hiring. Anticipating a rise in television revenue, and concerned about getting their fair share, the players sought an increase in pension benefits. A committee led by future Hall of Fame pitcher Robin Roberts went looking for a professional negotiator to bargain with the all-powerful owners, who were both united and well-organized.

Miller was recommended to the panel, which had its reservations about union leaders given the stereotypes of the day. The rank and file players, relatively uneducated and even less experienced with unions, had reservations as well. They were easily cowed by the owners, who told them they should be grateful to be playing a boys' game for money.

In the spring of 1966, Miller toured training camps in California, Arizona and Florida, speaking with players before they voted on whether to hire him as the executive director. With owners and their representatives speaking out against him, and managers able to further intimidate the players by conducting the votes, Miller lost up-or-down votes in front of the first four teams, but with Roberts, Jim Bunning and the team player representatives pushing the other 16 clubs harder, he won over the remaining camps. As Jim Bouton—who would later benefit from Miller's defense when Kuhn called upon the pitcher to recant the more shocking details of his 1970 book Ball Four—recalled in John Helyar's book, Lords of the Realm, "We were all expecting to see someone with a cigar out of the corner of his mouth, a real knuckle-dragging ‘deze and doze’ guy.” Miller, a "quiet, mild, exceedingly understated man," impressed the players, gained their confidence and was ratified as the executive director.

Miller educated the players about their rights and the importance of solidarity, and gradually began chalking up substantial victories. He implemented a dues structure and further beefed up the union's finances by securing licensing deals with Coca-Cola (1966) and Topps (1968). Players were able to flex their collective muscles by refusing to sign renewal deals or pose for new photographs until they received higher fees and royalties. In the spring of 1967, he conducted an anonymous salary survey so as to arm players with that information (at the time, the average was $22,000, the median was $17,000, and 6% made the minimum $7,000). In 1968, Miller and the union negotiated the first collective bargaining agreement in all of sports, securing a raise in the minimum salary to $10,000, standardized contracts, increased meal money, a formalized structure for grievances, and new scheduling rules. In the 1970 CBA, the players gained the right to have grievances heard by an independent, impartial arbitrator, which paved the way for the landmark Messersmith-McNally decision that created free agency in 1975.

In the spring of 1972 with the CBA expiring, Miller led the game's first work stoppage, a 14-day strike that centered around the owners' increase in pension contributions. The owners didn't believe the players would stay united, but they did until the owners finally acquiesced; 86 games were cancelled. Later that year, the US Supreme Court ruled against Curt Flood in his suit against Kuhn and the owners, a challenge to the reserve clause stemming from the outfielder’s 1969 refusal to accept a trade from the Cardinals to the Phillies. Flood argued that the reserve clause, which appeared to give teams the right to unilaterally renew player contracts on an annual basis, constituted indentured servitude, violating both the 13th Amendment and antitrust laws. In the next CBA, which went into effect in 1973, the players gained a limited right to salary arbitration, and "10-and-5" rights allowing them to veto trades if they had at least 10 years in the majors and five with their current club, and a reduction in the amount of service time necessary to reject an assignment to the minors from eight years to five.

In the wake of the Flood decision, Miller engineered another challenge to the reserve clause when Dodgers pitcher Andy Messersmith and Expos pitcher Dave McNally played the entire 1975 season without signing contracts (several players, including Simmons, had gone deep into seasons before signing). After the season, they filed grievances, claiming the right to free agency, because there was no contract for the team to renew. In December, arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled for the players, and once the owners' appeals to overturn the ruling—not to mention their attempt to lock players out of spring training—finally ran out, Miller and the union negotiated a new CBA creating a framework for free agency once players reached six years of service time. In the winter of 1976–77, the first wave of free agents began striking it rich, with Jackson becoming the game's highest-paid player via a five-year, $3 million deal with the Yankees. In November 1979, Nolan Ryan became the game's first player with an average salary above $1 million. From 1976 to 1980, the average salary nearly tripled, from $51,501 to $143,756.

After averting a strike in the spring of 1980—centered around teams wanting compensation for having lost players to free agency—Miller led a seven-week strike in 1981, resulting in the cancellation of 713 games (38% of the schedule) and the creation of a split-season format with first- and second-half division leaders meeting in an extra tier of playoffs. The resulting agreement created a tiered free agent system whereby teams losing premium free agents would receive compensation.

It's Time to (Finally) Elect Alan Trammell Into the Hall of Fame

The 65-year-old Miller retired as the executive director at the end of 1982, but remained active as a consultant, member of the union's negotiating team By the time of his retirement, the minimum salary was $33,500 and the average was $241,497. Miller returned briefly as interim director when his initial successor, Ken Moffett, was forced out due to the belief among players that he was too conciliatory towards the owners.

While there's room for debate as to whether the opening of the Pandora's Box of player rights was uniformly a good thing—nobody likes a work stoppage or seeing star players leave via free agency—Miller spent his career in baseball firmly establishing that the talents of major league players did not exempt them from basic workplace protections. He ensured that they get their fair compensation as attendance and revenues ballooned, far outpacing the growth of the rest of the economy.

Despite—or because of—of his revolutionary work, Miller was shamefully bypassed even from consideration by the Veterans Committee until 2003, by which point the vote had been extended to every living Hall of Famer as well as the surviving Ford C. Frick Award and J.G Taylor Spink Award winners (the broadcasters and writers). Once he finally got a spot on a composite ballot alongside other executives, umpires and managers, he received just 44% of the vote (35 out of 79).

Jackson, whom Miller's work turned into a millionaire several times over, embarrassed himself by striking out in spectacular fashion, sending in a blank ballot while telling reporters, "I looked at those ballots, and there was no one to put in." Mike Schmidt, who became the game's highest-paid player in the mid-1980s thanks to the leverage of free agency, similarly voted for nobody. Jackson eventually realized the error of his ways, and his comments stirred awareness among the electorate. Miller rose to 63% (51 out of 84 votes) on the VC’s 2007 composite ballot.

By that point, Miller was already braced for disappointment, saying, "When you’re my age, 89 going on 90, questions of mortality have a greater priority than a promised immortality.” Later that year, Bouton succinctly summarized Miller's chances on the 2008 ballot, by which point the process had reverted to a 12-member panel: "Marvin Miller kicked their butts and took power away from the baseball establishment—do you really think those people are going to vote him in? It's a joke."

Indeed, Miller received just three votes on a panel that elected Kuhn (who had received just 17.3% from the larger group the year before). It was a sick and twisted joke given that the labor leader beat the commissioner like a rented mule at every turn. But one look at the composition of the panel explained the result. Beyond the three writers on the committee, none of the three ex-players—Monte Irvin, Bobby Brown and Harmon Killebrew—played a single major league game in the post-reserve clause era.

Irvin spent 17 years working for the commissioner's office under Kuhn, Brown was an executive with the Rangers and then AL president after Kuhn stepped down, and of the six other owners and executives on the committee—John Harrington (Red Sox), Jerry Bell (Twins), Bill DeWitt Jr., (Cardinals), Bill Giles (Phillies), David Glass (Royals), and Andy MacPhail (Orioles)—DeWitt, Giles and MacPhail were legacies whose fathers (and the latter's grandfather) were on the management side during the Reserve Clause era. Giles, Harrington and MacPhail were part of management during baseball's late-1980s collusion scandal, the trial of which featured Miller as the lead witness. Glass was among the anti-union hardliners who caused the 1994 strike.

So frustrated was the 91-year-old Miller that six months later, with his candidacy not set to be reviewed for another 18 months, he took the unprecedented step of asking the Hall not to include him on another ballot, saying in a letter to the BBWAA (which only had partial input on the process):

"Paradoxically, I'm writing to thank you and your associates for your part in nominating me for Hall of Fame consideration, and, at the same time, to ask that you not do this again. The anti-union bias of the powers who control the Hall has consistently prevented recognition of the historic significance of the changes to baseball brought about by collective bargaining.

As former executive director of the players' union that negotiated these changes, I find myself unwilling to contemplate one more rigged Veterans Committee whose members are handpicked to reach a particular outcome while offering a pretense of a democratic vote. It is an insult to baseball fans, historians, sports writers and especially to those baseball players who sacrificed and brought the game into the 21st century. At the age of 91 I can do without a farce."

Like any great labor leader, Miller knew how to count votes before an election was held, and he knew when he didn't have them. When I interviewed Miller—still sharp in his old age—for Baseball Prospectus shortly after that release, he reiterated his stance, vowing not to show up for induction if the Hall went against his wishes and the VC elected him, referencing both Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman (who refused to run for president: "If elected I will not serve…") and comedian Groucho Marx (“I don’t care to belong to any club that will have me as a member.”)

Against his wishes, Miller was included again on the 2010 VC ballot (58%) and the ’11 Expansion Era ballot. While he received 11 out of 16 votes in the latter, one short of election, the presence of MacPhail, Giles, Glass and White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf, a collusion kingpin and strike hardliner, meant that Miller had to run the table among the other 12 voters to gain entry. That he came so close no doubt owed to the fact that of the six Hall of Fame players on the panel, five—Rod Carew, Andre Dawson, Carlton Fisk, Paul Molitor and Phil Niekro—had benefited from free agency.

Analyzing the Hall of Fame Cases for Don Mattingly, Steve Garvey and more

Before Miller passed away in 2012, his son Peter ruled out the family's participation in any posthumous honor by the Hall, writing: “No one in our family will attend or speak at any Hall of Fame ceremony regardless of the outcome of the Hall of Fame vote. It’s important for union members and the media to understand why, so that the story does not get misrepresented as ’sour grapes,’ personal pique, or anything of the sort."

When Miller was included on the 2014 Expansion Era ballot, his children repeated their stance, with daughter Susan calling the committee "cowards [for] doing it after he died." In the ensuing vote, managers Bobby Cox, Tony La Russa and Joe Torre were elected unanimously, while Miler and the other eight candidates were consigned to "six votes or fewer" territory.

Now that he's up for election again, voters—and Miller's supporters—face a paradox: is it more important to honor the man's wishes or to right a wrong by recognizing his place in baseball history, even in belated fashion? While I don't begrudge the family a permanent boycott of the Hall, I come down on the side of preferring that he's elected. One can't credibly tell the story of Major League Baseball without Marvin Miller, who revolutionized the game and its business practices. When he's honored, both his accomplishments and the stain of the institution's failure to honor him during his lifetime will be part of that story. The induction speech he never got to give would have been epic, but even without it, his legacy will long outlive those of the small-minded men who stood in his way.

With that, I've completed my review of the 10 candidates on the Modern Baseball ballot, having come down firmly in favor of votes for Miller, Simmons and Trammell. Voters have four slots to work with, but this is the rare instance that I don't think it's necessary to go full tilt, because none of the seven other candidates measure up. I suspect the voting results will differ from my ballot preference, but we'll find out on December 10.

Jay Jaffe is a contributing baseball writer for SI.com and the author of the upcoming book The Cooperstown Casebook on the Baseball Hall of Fame.