Nine Innings: The Fear-Inducing Yankees, Examining MLB's Troubling Trends and Banning the Shift

HOW THE YANKEES ARE SCARING PITCHERS OUT OF THE STRIKE ZONE

By Tom Verducci

Not only are the Yankees the highest scoring team in baseball, they are also the scariest. The Red Sox proved that last week at Yankee Stadium by refusing to attack the strike zone against them. New York’s lineup is so deep, and the triumvirate of Aaron Judge, Giancarlo Stanton and Gary Sanchez so imposing, it is scaring pitchers out of the strike zone.

Boston typically throws 64% strikes. But in three games in New York its pitchers threw just 56% strikes.

This is what reliever Matt Barnes did when asked to protect an eighth inning lead: fell behind Neil Walker 2-and-0 with two curveballs, fell behind Miguel Andújar 2-and-0, and fell behind Gleyber Torres 3-and-0. And those are the bottom three hitters in the Yankees’ lineup.

Barnes then threw Torres a 3-and-0 curveball, a pitch so absurd even Torres had to grin. It was one of only six curveballs thrown in the majors this season on 2,176 pitches thrown at 3-and-0. Barnes did throw it for a strike, but missed with his next curveball, putting what turned out to be the winning run on base. Craig Kimbrel came in and fell behind Brett Gardner 3-and-0, and at a full count yielded a game-deciding triple.

It’s not just the Red Sox who are being scared out of the strike zone. The Yankees see the fewest strikes in baseball—60.9%, matching the 2007 and 2009 Yankees as the scariest lineup in baseball since the 2004 Yankees (60.3).

Nothing drives offense more than the count, and the Yankees hit ahead of the count more than any team in baseball except the Dodgers. No wonder they are on pace to score the most runs by any team since the 2007 Yankees.

It was especially fascinating to watch the Red Sox avoid challenging Judge. Last year they held him to a .151 batting average, mostly by pounding fastballs up, many of which Judge would chase. This year? Different story.

Boston has thrown Judge a staggering 60% pitches out of the strike zone. He has chased only 11 of the 64 pitches he has seen outside the zone. Judge is slashing an absurd .524/.630/.857 against them. Overall, Judge has cut his chase rate from 23.1% last year to 18.4% this year.

The Yankees’ offense is as good as advertised. Pitching passively against them only makes them more dangerous.

BEST THING I SAW THIS WEEK: FREDDY PERALTA'S DAZZLING DEBUT ON THE MOUND

By Jack Dickey

The most exceptional things that happened in baseball this week are exceptional more for being bizarre than exemplary. Orioles righty Dylan Bundy made a start on Tuesday in which he surrendered seven runs and four homers without recording an out; he then threw seven scoreless innings on Sunday, allowing six baserunners total. The Reds went 6-1, and their 14th-in-the-NL pitching staff was improved by the arrival of Matt Harvey, who had a 6.77 ERA in his last season-and-change in New York before throwing four scoreless innings on Friday. (And Scooter Gennett homered in four straight games!)

But the week was not without unalloyed successes—and my favorite of them belongs to the Brewers’ Freddy Peralta, who made his big-league debut on Sunday at Coors Field. The 21-year-old Dominican righty, who had been pitching well enough at Triple-A Colorado Springs that he was pressed into duty when the stomach flu pushed Chase Anderson to the disabled list. So how’d he do? He struck out the first batter to face him, DJ LeMahieu, looking. He got the next one, David Dahl, to ground out. Then the next four met LeMahieu’s fate, but swinging: Charlie Blackmon, Nolan Arenado, Carlos Gonzalez, Trevor Story. Peralta struck out eight more guys after that, for 13 total. Oh, right—he also didn’t allow a hit until there was one out in the sixth inning.

#Brewers No. 9 prospect Freddy Peralta became the 1st pitcher in history (dating to 1908) to throw ≥ 5.2 scoreless IP with ≥ 13 K's while allowing ≤ 1 hit in his @MLB debut. More: https://t.co/abIem5n2IV pic.twitter.com/ptNJbmxn6A

— MLB Pipeline (@MLBPipeline) May 14, 2018

It’s a short list of starters who have debuted so dazzlingly, strikeout-wise, in the last 50 years: Only J.R. Richard, in 1971, and Stephen Strasburg, in 2010, whiffed more batters in their first starts, with 15 and 14, respectively. And by game score, only 24 pitchers in the last 50 years had debut starts better than Peralta’s. (Steve Woodard’s eight one-hit, one-walk shutout innings for the ’97 Brewers, good for a game score of 91, are the gold standard here.) Among the more recent outings on the list: Johnny Cueto for the Reds in 2008, Eduardo Rodriguez for Boston in 2015, and Nick Kingham for the Pirates just earlier this year.

Sure, a debut is just a debut, and that list contains plenty of pitchers who went on to fail. (Chris Waters and Scott Lewis made electric debuts in 2008, and neither threw a single pitch after 2009.) And Peralta’s repertoire didn’t look especially evolved. He threw eight curveballs and 90 fastballs, the fastest of which was tracked at 94.8 mph. He’s supposed to have a good changeup but we didn’t see it Sunday. Then again, that made his dominance all the more fun to watch. I have offered more than my fair share of grumbling about the superhuman fireballers who arrive in the bigs immediately capable of blowing all-star hitters away. Peralta wasn’t that: This scrawny neophyte overwhelmed hitters instead with a so-so fastball and lots of guts. And this Mother’s Day was his parents’ first time watching him pitch. So what if his spin rate’s not stellar? Something tells me his family is too proud to care.

EMPTYING THE NOTEBOOK: EXAMINING MLB'S CURRENT TRENDS, BRYCE HARPER'S EYE AND MORE

By Tom Verducci

In 46 seasons since the DH was added, it has never been harder to get a hit in the major leagues than it is today. You know the many reasons why, none bigger than the growth of bullpens. The average reliever today strikes out 9.2 batters per nine innings—which means your average bullpen guy strikes out guys at the same rate Sandy Koufax did.

It’s boom or bust baseball. Fewer balls in play mean fewer rallies, less strategy (while you wait for home runs), fewer bench players (due to stocked bullpens), more non-decisive pitches, and bigger yawning gaps without a ball in play.

Baseball ebbs and flows. We all know that. But this may be a good time to take stock in the extremities of the current trends—and how many trends are at work:

Baseball Per Game Rates in 2018

• Pitches: all-time high

• Pitches per plate appearance: all-time high

• Strikeouts: all-time high

• Balls in play: all-time low

• Sacrifices: all-time low

• Singles: all-time low

• Hit Batters: 118-year high

• Stolen bases: 46-year low

• Hits: 46-year low

• Pinch-hitters: 68-year low

• Pinch-runners: 76-year low

You have to go back to 1972 to find a season when there were so few hits. Otherwise, baseball in 2018 looks nothing like baseball in 1972. It takes almost 40 minutes longer to play a game with about the same number of hits. You have to wait 46% longer to see a ball in play today as you did in 1972.

Here’s a look at how the game has changed since the last time it had so few hits. (Plate appearances without the ball in play reflect strikeouts, walks, home runs and hit batters.)

Average MLB Game

| 1972 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

Plate Appearances | 75.3 | 77.0 |

Hits | 16.4 | 16.8 |

Strikeouts | 11.1 | 17.4 |

Plate Appearances Without Balls in Play | 25.5% | 35.5% |

Time of Game | 2:27 | 3:06 |

Time Between Balls Put in Play (Minutes:Seconds) | 2:37 | 3:45 |

***

The Red Sox and Yankees have played 299 games since 2003, postseason included. The teams have combined to score 3,077 runs in those games. The run differential is almost non-existent. The Yankees are +3 over 299 games.

The Rivalry, 2003-2018

| Red Sox | Yankees |

|---|---|---|

Wins | 146 | 153 |

Runs | 1,537 | 1,540 |

***

Just how good is Bryce Harper and his batting eye? The Nationals rightfielder has come to the plate 180 times this year and struck out lookingonce—and that was on a blown call. Third-year umpire Nic Lentz, 28, is the only umpire to call strike three against Harper this year.

Lentz rang up Harper on a 94 mph 0-and-2 fastball from Arizona lefthander Patrick Corbin on April 28. Harper immediately argued. According to the pitch tracking data from StatCast, Harper was right: the pitch was high and outside.

Nobody in baseball sees fewer strikes than Harper (55.3%).

***

The Dodgers have a host of problems—injuries, less depth after cutting their payroll by $54 million to sneak under the luxury tax threshold, and losing eight of 12 against the Diamondbacks, to name a few. But there’s something else going on that their hitters must know by now: they’re seeing far fewer fastballs.

Los Angeles has gone from the team that saw the most fastballs last year to the team that is seeing the least this year:

Fastballs Thrown vs. Dodgers

Year | Fastball Percentage | MLB Rank |

|---|---|---|

2017 | 57.2% | 1st |

2018 | 49.7% | 30th |

Yasiel Puig, off to a terrible start, is symbolic of an astounding year-to-year change. Puig has seen 140 off-speed pitches this year and still doesn’t have an extra-base hit against one. He is hitting .167 against sliders, curves and changeups.

RICK PORCELLO AMONG PITCHERS DITCHING THE FULL-COUNT FASTBALL

By Tom Verducci

From leading the league in losses last year to leading the league in wins this year, Boston righthander Rick Porcello has made one huge change: confidence in his secondary pitches.

The full count pitch is baseball’s sodium pentothal. It’s the truth serum that reveals a pitcher’s confidence in his repertoire. What do you choose to throw when you must deliver a strike?

For Porcello, almost two out of three times, that used to mean a fastball, either his sinker or a four-seamer. Fastballs get hit.

This year, Porcello has reversed his pitch selection when he gets to a full count. He rarely throws a fastball at 3-and-2, choosing instead to throw sliders or changeups 66% of the time in spots when hitters used to sit on fastballs.

Look at the massive difference it’s made in his results on full counts:

Rick Porcello on Full Counts

| Fastball Percentage | OPS |

|---|---|---|

2017 | 61.5% | 1.012 |

2018 | 33.3% | .580 |

It’s not just Porcello, either. As hitters have adjusted to hit velocity, pitchers on full counts increasingly are sowing doubt in hitter’s minds on what used to be a “fastball count.” From 2015 to 2018 the percentage of fastballs thrown on full counts has dropped from 62.5% to 59.9%—that’s about 900 fewer fastballs on full counts over a season.

“A lot of teams went to that high fastball a lot to combat launch angle,” said one manager. “But hitters have started to adjust to it, especially the more you throw. It used to be ‘breaking ball, breaking ball, show the fastball up.’ But why not continue with the breaking ball? Because sometimes you’re better off just [walking] the hitter and going after the next guy with a fresh count.”

THE TERRIBLE, HORRIBLE, NO GOOD, VERY BAD AL CENTRAL "RACE"

By Jon Tayler

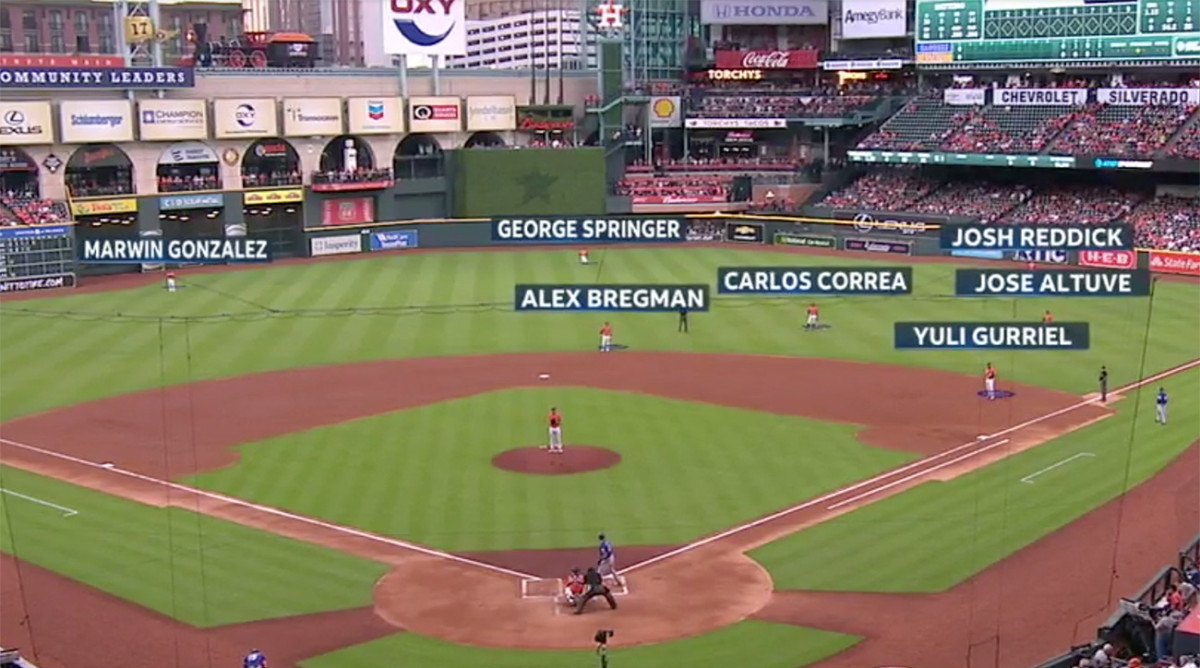

The Tigers aren’t supposed to be here. Having ditched its most valuable players and with no signings of consequence made this winter, Detroit entered this season as a clear rebuilding team. The goal was simply to play out the string and finish with a high draft pick, biding time between yesteryear’s contending Detroit squads and a potential future championship-caliber club with a roster comprised of rookies, past-their-prime veterans, and Quad-A filler. (See this lineup for proof—a one-through-nine that is Triple A in all but name.)

At the close of Sunday’s play, the Tigers’ collection of has-beens and never-weres sat at 17–22 on the season—a 70-win pace that, while perhaps a bit ahead of what was expected, is still decidedly bad. But for all of the Tigers’ machinations, that sub-.500 record has them a mere three games out of first place in the AL Central. By pure accident, they’re in third place and within striking distance of a playoff spot thanks to their residence in what is far and away the worst division in baseball.

Logan Morrison on Shohei Ohtani: 'He's Probably the Best Player in the World'

Here’s how low the AL Central has sunk. The Indians—who’ve won the division two years in a row and were widely favored to do it a third time—are in first place despite a 20–19 record, or an 83-win pace for a full season. The Twins are 1 ½ games back in second but two games under .500 at 17–19. Then come three straight rebuilding teams: the aforementioned Tigers, the Royals (13–27), and, boasting the worst record in baseball, the White Sox (10–27). Everyone but Cleveland has a negative run differential; Kansas City (-69) and Chicago (-67) rank 29th and 28th in that category, respectively. “Putrid” doesn’t begin to describe the state of affairs in the American League’s heartland. As FanGraphs’ Jeff Sullivan noted last week, the division’s collective performance may end up being the worst of any in the last 25 years.

How did things get to this point? Start with the fact that three-fifths of the Central entered this winter with no plans to contend or spend. The Royals, Tigers and White Sox instead shopped in the bargain bin this offseason, saving money for the future while signing cheap veterans like Francisco Liriano, Lucas Duda, and Joakim Soria. Those squads have their eyes trained far into the future, or at least on the minor leagues, waiting for the current crop of prospects to grow into productive major leaguers. Poor results in 2018 are no surprise (though the White Sox’ abysmal start is worrisome for a team that’s already started to graduate its top talent).

What is surprising is how Cleveland and Minnesota have stumbled out of the gate. The Indians, winners of 102 games last year, haven’t been right offensively, with a team OPS+ of just 93. Veterans Edwin Encarnacion (.201/.270/.410) and Jason Kipnis (.173/.256/.253) are showing their age, and new addition Yonder Alonso isn’t making any fans in Ohio forget the departed Carlos Santana with a .292 on-base percentage so far. The bigger issue, though, has been the bullpen: The unit’s 5.26 ERA is second worst in the AL, better only than Kansas City’s no-name collection of arsonists. Some of that can be blamed on fireman Andrew Miller missing two-plus weeks with a strained hamstring, but no one aside from him and closer Cody Allen has been anywhere near effective.

Watch: Francisco Lindor Wears Wrong Helmet At Plate

Minnesota, meanwhile, has a mediocre lineup and patchwork rotation holding it back. Young stars Miguel Sanó and Byron Buxton have been sidelined with injury, and veterans Brian Dozier and Logan Morrison have struggled through early slumps. A hot start for hard-throwing righty Jose Berrios has fizzled out, as he’s given up 18 earned runs in his last four starts over 18 1/3 innings. And offseason acquisition Lance Lynn has been one of baseball’s worst starters so far, with a 7.34 ERA and 59 ERA+ in 34 1/3 frames.

Both the Twins and Indians are more talented than they’ve shown, but the problem for each is that their slow starts have left them lagging outside of the division. With both the Yankees and Red Sox looking like world beaters, one of those two teams is practically assured of a wild-card spot, leaving the loser of the AL Central race to try to fend off the Angels, Mariners, Blue Jays and A’s for the fifth and final playoff spot. And with the division odds still firmly in Cleveland’s favor—the Indians stand a 89.9% chance to finish in first, according to FanGraphs—that’s bad news for the Twins, who have cost themselves dearly with their awful April and mediocre May.

The good news for both is that the rest of the season features plenty of games against the bottom of the division, with chances to fatten up against rebuilding squads—all of whom should get worse as they slough off their veteran talent this summer. Then again, as the Tigers have already shown, even tanking teams still win a few games every now and then, and in the decrepit Central, there are apparently more games up for the taking than we thought.

ROUNDTABLE: SHOULD MLB IMPLEMENT RULES TO BAN OR RESTRICT HOW DEFENSES CAN SHIFT?

Gabriel Baumgaertner: I hate to be the curt one with the terse answer but, in short, no. If they’re shifting you, learn how to hit the ball away from it. Or learn how to bunt. Stifling a strategic innovation because it may be annoying to some managers is probably the worst reason to change the rules in any sport. Outside of the pitcher and catcher, baseball doesn’t have fixed positions in the infield and outfield. In fact, I can’t wait for the day an opponent of the Cubs puts a six-man infield in front of Jason Heyward with a game on the line.

Michael Beller: I’ve typically resisted any idea to limit shifts. I think teams should generally be able to do whatever they want with their fielders, and I’m all for the game getting smarter. Plus, if you’re a hitter who regularly faces an extreme shift, the onus should be on you to force the defense to pay. I understand that these are generally players who get paid to hit homers, but there’s nothing wrong with a single, especially since a lot of these guys hit in the middle of the lineup. The guys coming up behind them are perfectly capable of creating runs, too.

Having said that, it’s safe to say that shifts are a factor in the sharp decline in balls in play. If one of the only ways to beat a shift is to hit a ball over it, and the best way to beat a hitter who’s trying to lift the ball is to throw it past him up in the zone, then shifts are going to lead to more homers and strikeouts. Homers and strikeouts are cool, but I think anyone who loves baseball would like to see more balls in play. If the league can produce data that definitively proves shifts are helping drive the reduction in balls in play, then I could get on board with some sort of limit on them. Short of that, however, I say shift to your heart’s content.

The Best Bets on the Fantasy Baseball Waiver Wire

Jack Dickey: With all due respect to the baseball commentariat, the most elegant opinion on the shift this week came from New York Times op-ed columnist David Brooks. Brooks retweeted a tweet of the extreme shift the Astros put on against the Rangers’ Joey Gallo, the pied piper of launch angle, into which Gallo had grounded out. “Be man enough to bunt,” he said.

Be man enough to bunt. https://t.co/lAjzSkWvhO

— David Brooks (@nytdavidbrooks) May 12, 2018

The fact that defensive shifting works—which is, in the end, why it persists and why we might dislike it—is a symptom of the flaws in the modern game, not the disease itself. Shifting works in large part because so many hitters have transformed their swings into boom-or-bust exercises. Each hitter who incorporates a little bunting and slap-hitting into his arsenal will help to turn the tide against aggressive shifting. The bunt works! But I’m not holding my breath.

Kenny Ducey: I love what is happening with the infield shift these days. Just last Thursday, the Yankees cost themselves three outs in four innings (and probably a run) thanks to their defensive alignment. The league as a whole has actually hit better than .305 against all shifts the past two seasons, according to FanGraphs. Their usage has increased so much year-to-year that teams have now gone completely overboard, which is the only way we will achieve a healthy balance of them. Let teams shift all they want and get burned by push bunts and bloopers. I don’t think it’s a major problem for the game, if anything it’s actually seemed to help offense. I think we’re in the regression stage of shifting, and hope we enter the regression stage of strikeouts soon. Bring on the contact revival, baby.

Connor Grossman: Rob Manfred has shown a clear willingness to explore subtle and dramatic changes to a game that prides itself on staying the same. Tinkering with the shift is chief among those changes. While an outright ban of nuanced defensive positioning would be an extreme measure, it seems worthwhile to consider implementing loose parameters at the lowest levels of professional baseball. It wouldn't be the first time MLB used the minor leagues as a test tube for new rules. So why not see what happens in Low A ball when you must have two infielders to the left and right of second base? That being said, this shouldn't be a high priority for Manfred & Co. As others have mentioned, the sport should focus on generating more action (balls in play) and speeding up pace of play. One day this issue will come to a head if the game doesn't correct itself, which it often finds a way to do.

Back From a Near Career-Derailing Injury, Dustin Fowler Is Savoring Every Moment

Jon Tayler: But beyond that, it feels wrong for the league to ban something simply because it doesn’t like it. This isn’t something like spitballs or steroids. Shifts are neither illegal nor unfair; they’re an organic strategy to get more outs. If hitters don’t like it, there are ways around it, such as putting the ball in play to the other side of the infield, or they can keep on homering, as there’s no shift in existence that’ll solve that. Plus, banning shifts means more offense (in theory), which means more runs and more pitching changes, which means longer games—the bane of Rob Manfred’s existence. Why would MLB, so zealous about pace of play, want to do something that would virtually guarantee more minutes added to the clock?

Let the game rule itself. Like natural selection, the shift will be subject to the forces of evolution; hitters will adapt or die. MLB needs to keep its thumb off the scale and let its own product live.

'14 Back': The Epic 1978 Red Sox-Yankees Rivalry To Be Featured in Upcoming SI TV Documentary

Tom Verducci: Baseball bears the same responsibility to keep the game attractive without solely relying on “the game corrects itself.” But I’m not sold yet that outlawing shifts is needed.

Shifts are a slight net positive when it comes to run prevention. They do open holes, but they mostly take hits away from lefthanded pull hitters, especially those that don’t run well. I’m not sure I want to “reward” one-dimensional hitters.

Besides, batting average on balls in play this year (.295) is higher than what it was every year from 1938 to 1993. It has remained in a rather small range (.295-.303) for the past 25 years. Baseball’s biggest problem is balls not in play. That should be the sport’s focus.

THE METS AREN'T ALONE WHEN IT COMES TO BATTING OUT OF ORDER

By Gabriel Baumgaertner

For Mets fans, that 11–1 start must feel like ages ago. That was confirmed in a most embarrassing fashion this week when the team lost a runner in scoring position after batting out of order in a 2–1 loss to the Reds. The brief comedy of errors unfolded like this: Asdrubal Cabrera doubled in the first inning to send Jay Bruce to the plate with two outs until Reds manager Jim Riggleman approached the umpires with his lineup card in tow.

What's going on here? An interesting start to the game... pic.twitter.com/sWYLrowB9O

— SNY (@SNYtv) May 9, 2018

Somehow, the Mets had submitted a lineup card with Cabrera batting second, but Wilmer Flores hit in the second spot in the first inning. Stranger yet, the Mets publicly released a lineup card with Flores, not Cabrera, batting second. The media thought Flores was batting second, the fans thought Flores was batting second, and so did the Mets … the only ones who had Cabrera in the two slot were the Reds and the umpires. That triggered an even more bizarre set of circumstances: Flores’s at-bat was legal because Riggleman did not alert the umpires after Flores struck out. Since Riggleman raised the question after Cabrera doubled and before Bruce took a pitch, home plate umpire Gabe Morales ruled that Bruce would be ruled out with a putout to the catcher—Rule 9.03(d)—since the Mets had batted out of order in the inning.

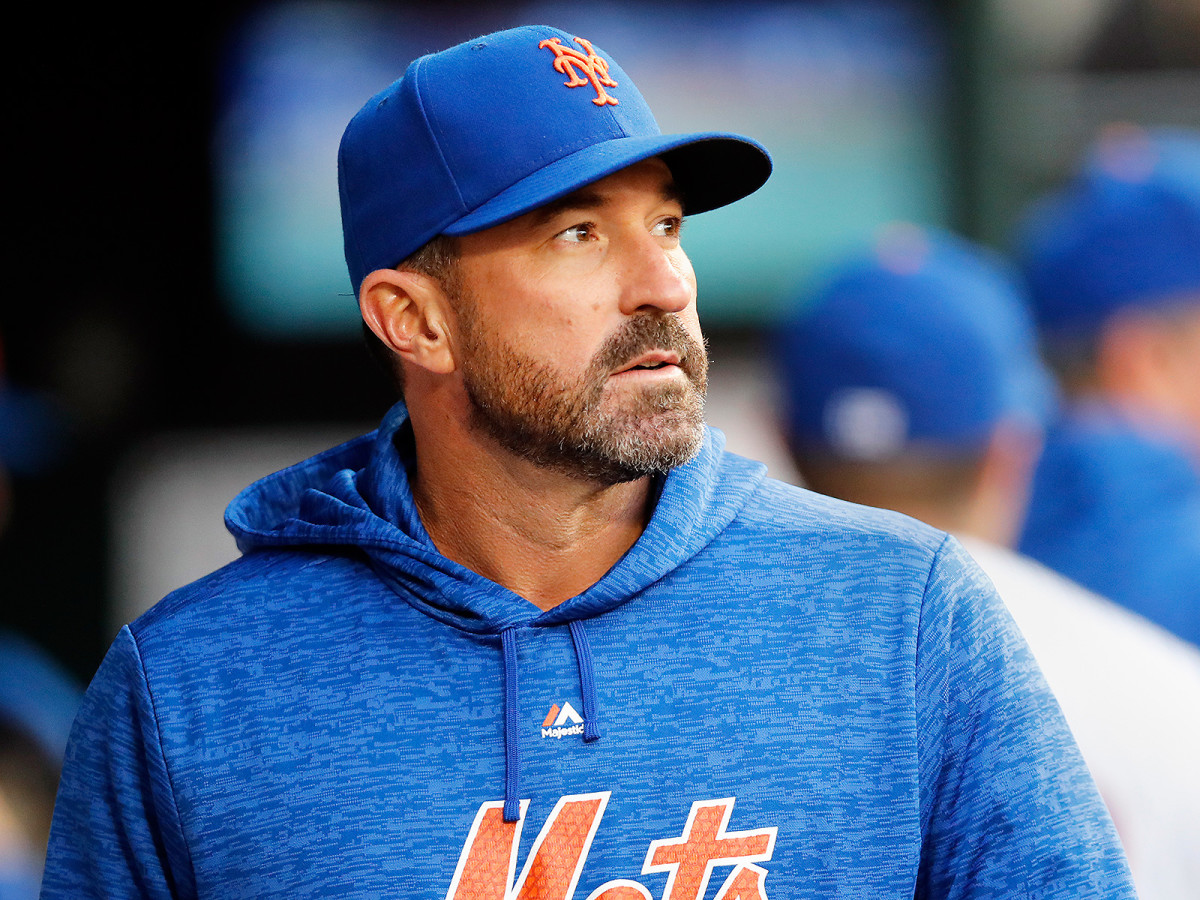

Bench coach Gary DiSarcina is typically responsible for writing the lineup card, and first-base coach Ruben Amaro Jr. delivered it to the umpires before the game. Manager Mickey Callaway excoriated himself after the game for the error, as it cost the Mets a runner in scoring position in a game they’d go onto lose 2–1.

WATCH: Mickey Callaway explains what went wrong today with the lineup card, leading to the Mets hitting out of order in Cincinnati. pic.twitter.com/0URW3nbkub

— SNY (@SNYtv) May 9, 2018

The Mets deservedly became the day’s laughing stock, but it may have been exacerbated by their reputation as Major League Baseball’s longtime laughingstock. Ryan Braun batted out of turn for the Brewers two years ago and was called out. In 2013, Giants manager Bruce Bochy—renowned as one of the game’s most knowledgeable managers and authorities on the rulebook—sent up Buster Posey out of turn, who subsequently had an RBI double wiped out once Dodgers manager Don Mattingly alerted the umpires. In short, it happens—it just made bigger press because it felt like a fitting occurrence for the struggling Mets.

It’s an inexcusable error on Callaway’s behalf, but it’s hard to believe the rookie manager will ever make a similar mistake in his managerial career.

COMEBACK KIDS: THESE YANKEES HAVE THE SAME LOOK AS THE '09 CHAMPS

By Kenny Ducey

In 2009, the Yankees found a little magic. A collection of greying stars came from behind to win 51 of their 103 games, according to the Elias Sports Bureau, including 17 walk-offs. They were impossible to get out late, hitting a league-leading .295 after the seventh inning with a whopping .890 OPS. Somehow, some way, a team which probably should have spent the fall curled up in front of the fireplace found themselves winning the last game of the postseason.

Though the 2009 team's success was a tad unexpected after missing the 2008 postseason, it made a little sense, at least. Their starting lineup included Derek Jeter, Alex Rodriguez, Jorge Posada and Johnny Damon. These were names synonymous with late rallies and postseason triumphs, two proverbial ‘things that don’t show up in the box score’ but each contender wants sprinkle into its clubhouse. Throw Mark Teixeira and CC Sabathia into the mix—added on big free-agent contracts—and you can begin to see the blueprint for a reinvigorated crew with something left to play for.

These current Yankees—who tallied their 11th comeback victory this week, and fourth via walk-off—sure feel a lot like those Yankees. They’ve scored a league-leading 73 runs in the seventh inning or later, coupled with an .822 OPS. Simply put, opposing relievers have struggled shutting the door on this team.

The Yankees and Red Sox Are (Again) the Kings of Baseball in Latest Power Rankings

These baby Bombers don’t have the same resumes. They have one October run, two postseason series victories and one wild-card win. If you ask them, that’s really all they need to feel confident about their chances when they’re down late.

“I think a lot of it goes back to last year in the postseason,” Aaron Judge said. “A lot of these guys got their taste of what a postseason atmosphere is. Now we play in [close games], man, it’s just another day. It’s just, go out there and get the job done.”

It might help explain why Aaron Judge and Didi Gregorius are so calm at the plate in crunch time, but it doesn’t make the late-game heroics of Gleyber Torres and Miguel Andujar any more reasonable. There is something inexplicable about these neophytes’ innate ability to flip should-be losses into victories. Perhaps a little magic is at play, just as it was the last time the Yankees won it all.

WHY WE SHOULD HAVE SEEN MITCH HANIGER'S BREAKOUT COMING

By Michael Beller

Breakouts come in all shapes and sizes, and from all kinds of players. Some are predictable, while others are entirely unexpected. One of the breakout stars this year seems to be in the latter category at first blush, but a deeper look reveals his emergence isn't much of a surprise at all. Mitch Haniger is the breakout we should have seen coming.

To sum up the preface to Haniger’s emergence: He was a first-round pick who hit at every level of the minors, including one huge year at Triple A. He played like an All-Star in his first real chance in the majors, and all of his cosmetic numbers were supported by the nitty-gritty peripherals behind them. Finally, 2018 would be the first season of his career in which he had a guaranteed spot in his team’s regular lineup. That’s the perfect formula for a breakout season.

Evan Longoria on Rays in Tampa Bay: 'Somewhere Else Might Be Better'

All the elements were in place for 2018 to be a career season for Haniger. He had the sort of good-not-great season in 2017, his first extended look in the majors, that typically portends a breakout. Haniger slashed .282/.352/.491 with 16 homers and 25 doubles in 410 plate appearances last year. He didn’t make enough trips to the plate to qualify for the batting title, but if he did his 129 weighted runs created plus would have tied him with Nolan Arenado for 32nd in the majors. He racked up 3.0 bWAR in his 96 games, which puts him on a 162-game pace for 5.1 bWAR. By comparison, George Springer was worth 5.0 bWAR last season. Haniger’s year fell short of great only because of the half-season sample. On a per-game basis, it measured up.

His peripherals in 2017 supported his quality stat line. He had a 22.7% strikeout rate, perfectly reasonable in the modern game. His 7.6% walk rate was only slightly lower than league average. The .338 BABIP was higher than league average, but supported by a 37.3% hard-hit rate, which would’ve ranked 34th in the majors, and 16.9% soft-hit rate, which would’ve been in the top 60. His average exit velocity was 87.4 mph, also better than league average. In other words, Haniger hit the ball hard a lot during his rookie year.

Last year wasn’t Haniger’s first big season as a professional. In 2016, when he was still in Arizona’s organization, he had a monster season at Triple A Reno. He started that year at Double A, but moved up to Reno about halfway through the season. Haniger played 74 games with the Aces, hitting .341/.428/.670 with 20 homers, 20 doubles and 64 RBI. That earned him a cup of coffee with the Diamondbacks, but the team shipped him to Seattle in the offseason for Jean Segura.

There’s still more. Haniger has the pedigree of a first-rounder, going to the Brewers in the sandwich round of the 2012 amateur draft at pick No. 38 overall. It may have taken him longer to get through the minors than the typical first-round pick who eventually becomes a breakout player in the bigs, but he progressed every year. He never forced his way to the majors, but he never stagnated, either.

Haniger didn’t come out of nowhere. He was right in front of our face all along.

EXTRA INNINGS

FROM THE VAULT: CELEBRATING THE LIFE OF ROY HALLADAY

By Connor Grossman

The late, great Roy Halladay would have turned 41 on Monday. The baseball world is still coming to grips with his unexpected passing in a plane crash last November. One of the premier pitchers of his generation, Halladay's time will come to be honored in Cooperstown. It's hard to fathom that he won't be there to take part in the celebration. We can only hope the Blue Jays, Phillies and Major League Baseball continue to honor Halladay, his family and his terrific career.

Tom Verducci wrote a terrific piece in the April 5, 2010 issue of SI that detailed what "makes Roy run." He brilliantly peeled back the curtain on one of baseball's most fascinating, talented figures. Enjoy the excerpt below and find the entire story here.

Halladay is 32 years old, has two sons, has earned $73 million and is due another $75.75 million over the next four seasons. He has won 148 major league games and has a .661 winning percentage—only four pitchers since 1900 have had a better winning percentage with that many wins: Whitey Ford, Pedro Martinez, Lefty Grove and Christy Mathewson. Halladay is widely accepted as the best pitcher in baseball. And this spring he made darn sure he was the first one to arrive for work each morning at the Clearwater spring training complex of his new team, the Phillies.

Halladay reported at 5:30, 90 minutes before sunrise, four hours before the Phillies were required to be in uniform, and 15 minutes earlier than when he first showed up in camp in early February. He moved up his arrival once pitchers Kyle Kendrick and Chad Durbin tried to beat him through the clubhouse door. "We had to give him his own swipe card at Rogers Centre," says Kevin Malloy, the clubhouse manager in Toronto, where Halladay played from 1998 until his trade to Philadelphia in December, "because he would get in before anybody else. If you saw all the work that Roy put in for the four days before every start—all the conditioning, all the video work, all the studying—you would cry if he didn't come out of that game with a win."