Prospect and Pariah

The first thing to understand about a baseball game involving Luke Heimlich—the Oregon State pitcher who in 2012 pleaded guilty to one felony charge of molesting, at 15, his six-year-old niece, who nevertheless claims innocence, who this season leads the nation in wins—is just how normal it can feel. Nestled mid-campus in Corvallis, Goss Stadium hews to game-day rituals seen forever in ballparks big or small, coast to coast: No matter the paycheck or persona or police record, each player comes packaged the same old way. It is one of the sport's charms.

So it was late in the afternoon of April 19, when winter broke, the sun baked the ground and archrival Oregon made its first appearance of the year. The sound of batting practice, lovely even when—kank!—metallic, blended with rock standards blaring from stadium speakers. Heimlich, owner of a nation's-best 0.76 ERA in 2017 and once a lock for early-round money, aired out his left arm, long-tossing on the warning track. Two dozen windbreakered scouts, even those told by their teams not to bother, eyed him. One spoke of Heimlich's command of four pitches, his ability to hit spots at will—despite orders not to discuss him at all.

Of course the sound of scouts parsing talent, muttering under their breath with a crowd—3,692 tonight, a regular-season record—filing in, is a ballyard staple. Soon, too, came the P.A. man announcing the starting lineups; a local braving the national anthem; the ceremonial first pitch. As the Oregon players returned to their dugout, a middle-aged man greeted them from the stands with a resounding, "Go, Beavs! Ducks Suck! Hate Ducks! Ducks Suck!"

Yes, minutes later, the willfully thick could watch Heimlich, 22, standing alone atop Oregon State's highest dugout step and deem it almost routine. After all, the Beaver faithful had seen him there, poised to take the mound, so often in the previous three years; his fastball was now touching 96 mph, his ERA had spiked some, but the night's starter didn't seem all that different. If it weren't for the legal glitch that last year unearthed his juvenile record as a sex offender, they could almost convince themselves they were in for a night of baseball as usual.

But who, in the era of Too Much Information, can be that single-minded? College campuses, especially, exist now in a state of hypervigilance on matters involving sexual violence, predation and institutional response, and Oregon State's own history—stained by the 1998 gang-rape involving two Beavers football players and restored by a president who, until the Heimlich affair, was lauded for his sympathy for survivors—has left the school particularly woke. En route to the ballpark, in fact, one could grab the latest issue of the student weekly, The Baro, with a cover headline CONSENT IS MANDATORY and four stories on sexual assault dominating the pages inside.

So it was no shock to hear the Goss Stadium PA announcer warn, beforehand, that "racist or sexist" behavior toward players or coaches or team representatives would not be tolerated. But Heimlich's presence had a way of making the familiar uncanny, of charging even that benign voice, blending as it did with hundreds of others as the evening progressed. Some of them—still shaken by last June's revelation of Heimlich's 2012 guilty plea in Washington state, his overnight switch from major league prospect to national pariah, and OSU's decision to let him return this year—spoke softly.

"It felt like a betrayal," said Madeline Gorchels, 24, who is so devoted to Beavers baseball that she followed the team to Omaha last June for the College World Series and slept in a tent. "Goss Stadium had been a safe place for me, and suddenly it was tainted by the worst associations of my life."

Gorchels was sexually assaulted by a teenage neighbor at five years old, and the Heimlich news left her in a despair so searing that she spent two hours in a closet, trembling. But she felt it important this season to bear a kind of witness, attending three of Heimlich's earlier starts, clapping for every Beaver but him, taking heart from how she managed to stay cool. Tonight's game felt different. "It's harder than usual," Gorchels said from her family's seats along first base, watching Heimlich wind up. "Things are kind of ... um, bubbling up."

Other voices rose from within; in truth, it's impossible to watch Heimlich pitch now without wondering. A glance at the dugout: What do his teammates, especially the ones with sisters, think? A glance at the scouts: Who will dare draft him? And, always, a glance at Heimlich himself: Was he guilty? Is he a pedophile? An innocent? And why wonder about him at all? What about the victim?

Heimlich, a senior majoring in speech communication, knows that the voices are out there—loud, soft or nagging inside people's heads—each time he pitches or goes to a store or meets someone new. Two days before the Oregon game, he tried explaining to SI his strategy for living with society's most despised label. He didn't flinch when it was suggested that some consider him a monster.

"That goes down to what I can and can't control," Heimlich said. "I can worry about the draft, I can worry about what teams think, I can worry about what fans think. Or I can control what I can control. I can compete. I can give it everything I can when I'm on the field, I can prepare as good as I can and not worry about that stuff. Or I can worry about a lot of what-ifs."

Now it was game time, 6:03 p.m. PDT, crowd noise rising. His teammates and Oregon waited. Heimlich heaved a deep breath. Then, for the 11th time since his future cracked, he stepped forward into a game, trailed by questions that will never die.

What about that little girl?

What about her?

And this, coming in from afar, a voice that's less about Heimlich than it is about us:

"What's the kid supposed to do now? Kill himself?" says a Division I head coach who has watched Heimlich closely. "I have a lot of professional baseball friends who swear they're not going to touch him... . I mean, he can't go to Japan. No independent team is going to sign him. No pro team is going to draft him. What's he supposed to do?"

****

Wavering on whether to read further? Understandable. This may be the worst sports story ever told. Yes, there are plenty of vile candidates, and both the pedophilia at Penn State and the spree of sexual abuse by a U.S. Olympic team doctor occupies their own horrifying classes. But once their crimes surfaced, Jerry Sandusky and Larry Nassar never had to be placed in an athletic context again. Trials began, reforms were enacted; each was locked away. The games and meets went on without them.

Luke Heimlich is still here. Last June 15, a week after The Oregonian/OregonLive broke the story of Heimlich's 2012 guilty plea, Heimlich withdrew from the team's College World Series roster and university president Ed Ray released an 11-paragraph letter that unequivocally declared, "the young girl in this matter ... was the victim of wrongdoing," while announcing: "If Luke wishes to do so, I support him continuing his education at Oregon State and rejoining the baseball team next season."

In allowing for that combination, Ray overnight made his school and city a nexus for two of mankind's oldest obsessions: abominable behavior and exceptional talent. Here in one 6' 1", 197-pound package, draped in university orange and black, stood an embodiment of both—in the extreme.

"There's nothing worse than being a sex offender or a child molester," says Elizabeth Letourneau, an expert on juvenile sex offenses at Johns Hopkins. "You could be a murderer and you don't face the same kind of social opprobrium that you do if you're a known sex offender."

"Outstanding," says Yale coach John Stuper of Heimlich, who shut out the Elis in last year's NCAA regional. "Then I'm reading how he'd be a second-round pick and thinking, This must be one of the strongest drafts in history. We've played big-time programs: LSU, South Carolina, Texas A&M. But this kid's ceiling is higher than any college pitcher I've seen in my 26 years here. He'd be my first pick."

So it is that the Oregon State baseball program, a two-time national champ and the school's standard for NCAA excellence during coach Pat Casey's 24-year tenure, assumed the features of some odd new beast. Fans delighted by last year's 56–6 season and hoping for a redemptive run to Omaha this June had no shot at sport's usual win-or-lose clarity. Heimlich's official return in February—probation completed, criminal record erased, publicly denying for the first time his niece's account—ensured a season marred by real-world issues like victims' rights, the power and reliability of child testimony, the merits of rehabilitation, legal tactics, shame, faulty bureaucracies, and, of course, perception and public image.

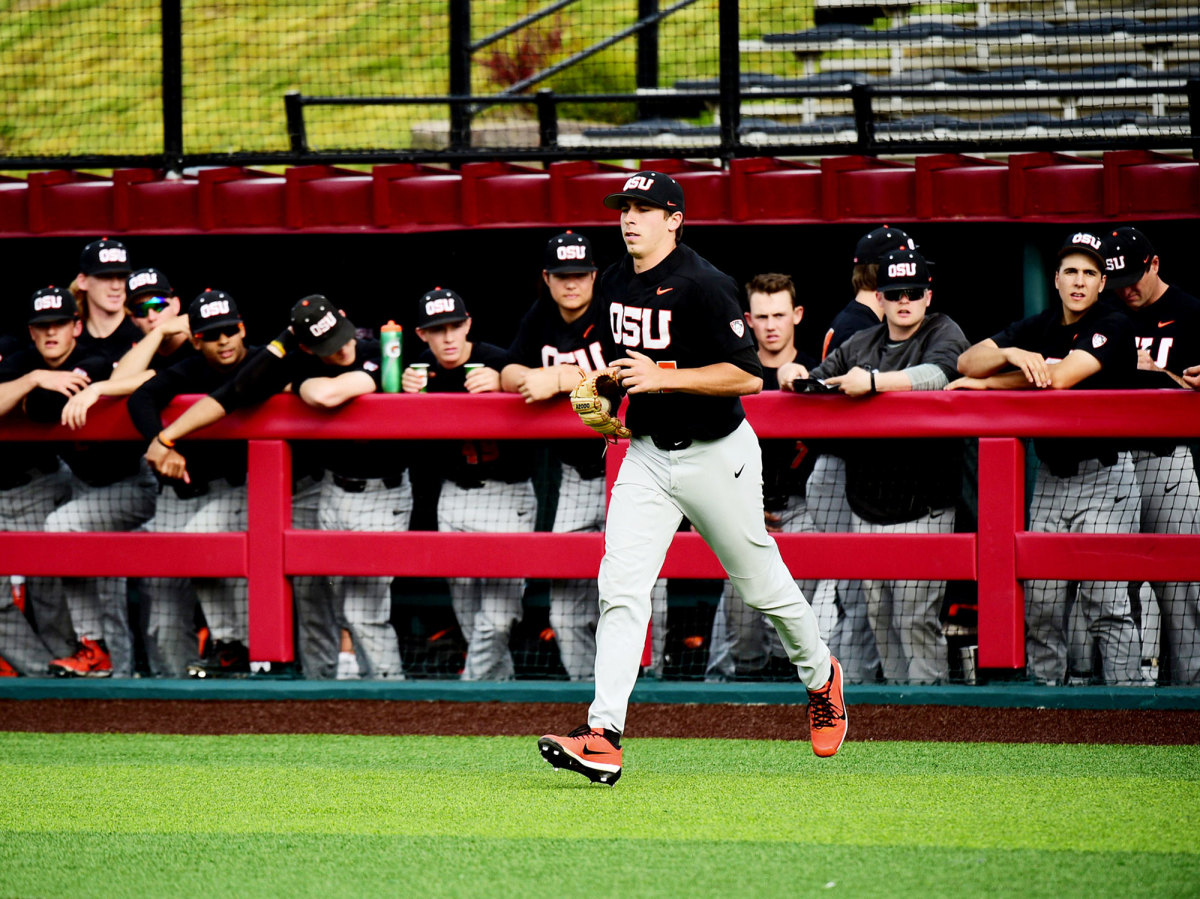

Batter up? Even for those able to tune all that out, there was still the matter of Heimlich himself: dominant yet elusive; again the Beavers' Friday night ace but wiped from team promotions; declining to speak to media but winning, week after week. The occasional columnist weighed in, condemning his scholarship and presence, but college baseball is second-tier most everywhere but Corvallis: There were no protests at road games and little heckling. Through May 13, Heimlich was 12–1, with a 2.94 ERA, 115 strikeouts in 89 innings and three Pac-12 Pitcher of the Week awards. Administrators love to call athletics a school's "front porch." None envision a child molester standing under the light.

Yet by the most measurable metric, at least, that image has barely registered. The OSU Foundation is on track to surpass last year's donation total of $132 million. "Overwhelmingly positive from alumni," says athletic director Scott Barnes of the reaction to Heimlich's return. "We are at a record-high, all-time, historic high in number of season tickets for baseball."

Still, if Travis Terrall, 52, is a measure, such support hasn't come without anguish. A 1989 grad and father of two current students, the lawyer from Tualatin usually revels in Oregon State athletics. "This is the place I love, but my feelings and thinking have evolved," said Terrall midway through the fifth inning, with OSU up 3–1 and Heimlich's slider humming: five innings, 10 strikeouts, one walk. "By now? He's on my team; I'm rooting for him. But initially? You're so disgusted you just want him to go away.

"Then you think, Our system isn't set up that you pay forever for something you did at 15. But it's not like he had a gun and robbed a bank. He violated a little girl. It's so conflicting."

Indeed, Ray's decision to let Heimlich play again has been deemed everything from tin-eared to judicious to appalling to even brave, considering that the easiest p.r. play would have been to send Heimlich packing. "I was very surprised," Gorchels says. "Especially at this cultural moment, coming at it from a very cynical, covering-their-asses perspective: How are they doing this? In this moment of #MeToo, where we're finally listening to women, how can they say, 'We don't do that at Oregon State?'"

Ray, who declined repeated SI requests for an interview, at the time cited Heimlich's academic record (a 3.3 GPA), his "positive" role as a student-athlete and the school's adherence to U.S. educational guidelines regarding openness to those with a criminal record. Brenda Tracy's gut tells her there's another reason: "Because he's a great pitcher, and they're winning."

Tracy isn't being flip. Just thinking that about Ray or Oregon State brings her to tears. When, in 2014, she stepped forward to reveal herself as the victim of the 1998 gang-rape (a case in which, though Tracy never recanted, she eventually did not press charges), Ray's response changed her life. Though it occurred five years before he came on as president, Ray wrote a public letter personally apologizing for the university's chilly handling of her accusation, paving the way for Tracy's hiring as an OSU consultant and leading to her current career speaking to colleges, teams and legislators nationwide on sexual violence.

"Ed Ray set an amazing example," says Tracy, of how a university leader can help change the culture. But meeting with Ray a few weeks after the Heimlich story broke left her baffled. It wasn't just his repeated talk about a "second chance," which conflicted with Tracy's belief that Heimlich's presence in an Oregon State uniform helps normalize child sexual abuse. It was the president's uncharacteristic vagueness. They discussed a change in student disclosure rules, but Ray wouldn't answer when Tracy asked how the university first became aware of Heimlich's sex offender status. Indeed, citing privacy restrictions, OSU officials have yet to confirm what the school knew about Heimlich's crime, and when.

"Part of taking on these issues is being accountable," Tracy says. "We've all been asking: When did you know? How did that process go? Was he in the dorms? Was he doing camps with kids? What if there were camps with kids, and parents didn't want to send their kids? As a public we're supposed to make informed decisions, but we can't if we don't know what's going on.

"I'm confused and hurt. I don't mean to get emotional, but ... I am so grateful for what OSU has done for me and never want to sound like I'm not. But it really did hurt me when this whole thing unfolded. Because I don't understand it."

"What's the kid supposed to do now? Kill himself?"

****

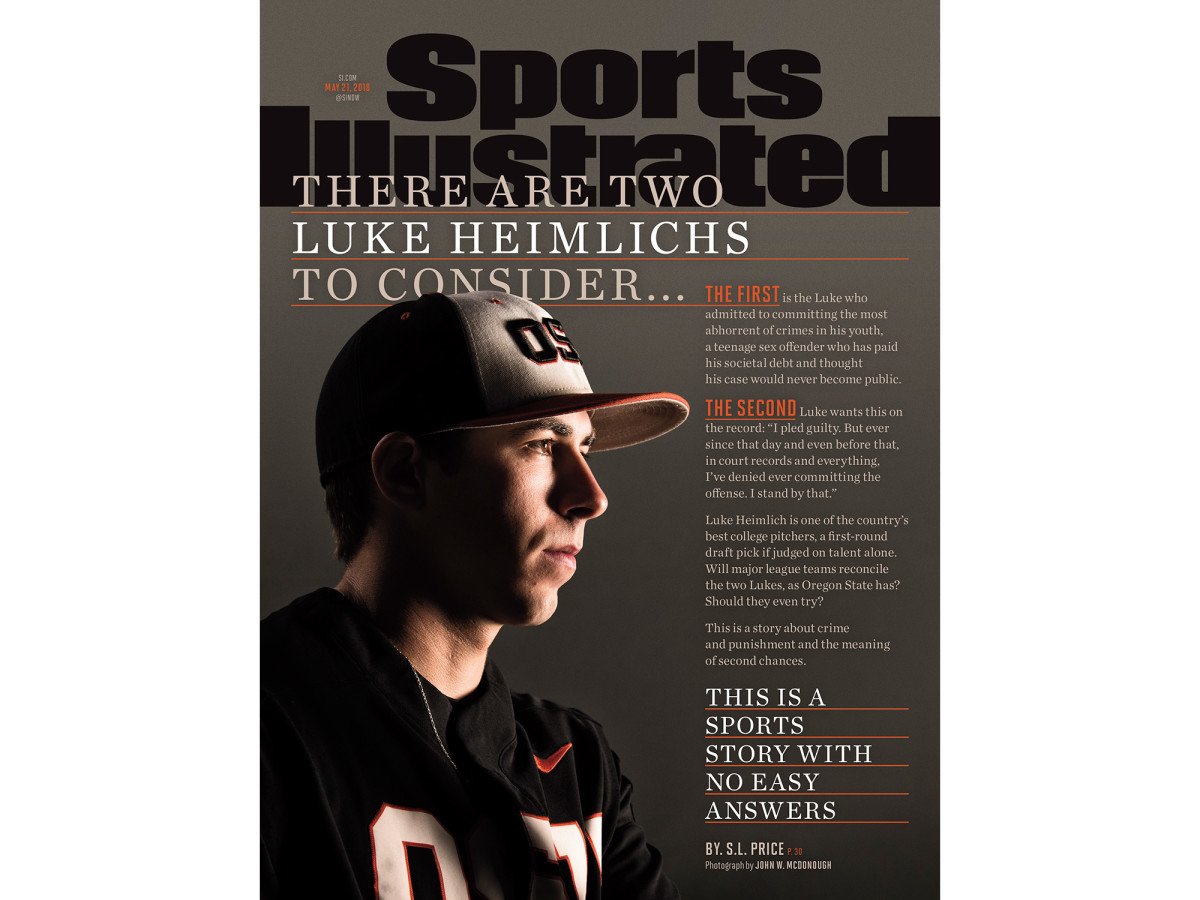

Maybe Tracy should stop trying. Really, the possibility of understanding this story, precisely and whole, may be impossible. Because there are two Luke Heimlichs to consider. The first is the Luke of horrible accusation and subsequent admission, the Luke of prosecutors and legal pleas and carefully parsed statements released by his lawyer. The first is Luke the perpetrator, the confessed child molester who from 2012 to '17 diligently paid his societal debt and by all standards of American jurisprudence—if not society—has reformed, statistically poses little threat and is entitled to get on with his adult life. There's every reason to believe that Luke is real.

"I admit," Heimlich declared in his seven-page "Statement on Plea of Guilty," written in his own hand and then signed on Aug. 27, 2012, in an open Pierce County juvenile courtroom, "that I had sexual contact with my niece."

The second Luke, who first appeared on Feb. 1 in a lengthy story by the twice-weekly Portland Tribune, contradicted the first Luke. Neither second Luke nor his family was quoted in the piece. But their account, confirmed by Heimlich to SI and reportedly bolstered by family released court therapist reports and polygraph test results, described a Luke who consistently denied the accusation to family and counselors, and who accepted a plea deal only to avoid a trial and jail time and to keep his schooling and baseball on track.

There's some reason to believe that Luke, too, is real. To start, the girl's mother, the first person told by her then-four-year-old daughter that her uncle had been touching her inappropriately, agrees that Heimlich always denied—outside the legal system—any wrongdoing. "Even back then, he said he didn't do it," said the girl's mother. "I understand. I get it. But I heard it come out of her mouth. And I know the way she was raised, and what she was allowed to see. There's just no doubt in my mind that he did what she said he did."

The second Luke, the Luke professing innocence, talked to SI on the morning of April 17, in a large suite at Goss Stadium called the Omaha Room. He declined to make available the court documents given the Tribune, or to make available his parents or lawyer for interviews; his most recent lawyer, Stephen Ensor, didn't respond to repeated requests for comment. For more than an hour, though, Heimlich maintained eye contact and answered every question.

"I've had an incredible support system in my family," he said. "I feel confident in who I am. I know the truth of the situation. I can't convince you. I can't convince the readers. But I know the truth and I'm confident in that. And if I'm not focused on what other people say and what other people read, ultimately I'm going to be all right."

The first Luke will make that difficult. The second youngest of eight children, Heimlich grew up in the Tacoma suburb of Puyallup. His father, a construction manager, is an ordained pastor, and his mother is a social worker who home-schooled all the kids in a rambling four-bedroom, 7,000-square-foot house on the outskirts of town. According to the probable cause document, filed in Pierce County Juvenile Court on March 29, 2012, it was there, when Luke's parents were looking after their granddaughter while the girl's parents worked, that the girl was left alone with Luke.

According to the document, which alleged that Heimlich committed two counts of "child molestation in the first degree," the girl told investigators that Heimlich brought her to the floor in the middle of his bedroom, "pulled down her underwear and with his hand he touched her private part... . She said that she told him to stop, but he wouldn't." The girl also said that "Uncle Luke" ... "touched her on both the inside and outside of the spot she uses to go to the bathroom. She said that it hurt her... . She said that the first time the respondent touched her she was four years old and that she was six years old the last time he did this."

Three months after the girl's first mention of illicit contact, in the fall of 2009, her mother and father, one of Luke's brothers, finalized their divorce after seven years of marriage. The mother insists that a custody dispute had no bearing on the accusations, saying that she never raised concerns about Luke and her daughter in custody proceedings. Luke's brother has maintained majority custody ever since. He was the one who, after questioning his daughter in 2011, initiated what would become legal action against Luke by taking her to a Child Advocacy Center, where he shared her accounts and allowed a forensic interview. He and Luke have barely spoken since. Asked if such silence indicates that his brother doesn't believe him, Luke said, "I don't know."

I am so grateful for what OSU has done for me and never want to sound like I'm not. But it really did hurt me when this whole thing unfolded. Because I don't understand it.

"I know—and he has said—that he sides with our daughter," the mother says of her ex-husband. "But it is a tricky situation to be in. He does not really have contact with Luke; they will see each other at big weddings where everyone's invited, but they don't call each other. He doesn't come over when just Luke's going to be there; he won't attend family camping trips if Luke is going to be there. Clearly there is tension. But it's his brother. He loves his brother."

Given the desire to safeguard his daughter and his respect for his parents, who firmly support Luke, it's no wonder that the brother has never commented publicly on the case. Approached by SI outside his home in April, he shook hands, said "I'm good," and politely declined to speak. Then he walked back inside. His daughter, grinning and bubbly and shooting baskets in the driveway, waved at the stranger driving away.

****

Second Luke wants this on the record.

"I pled guilty to it," he said of the child molestation charge. "But ever since that day and even before that, in court records and everything, I've denied ever committing the offense. I stand by that."

Asked, minutes later, if he ever touched his niece inappropriately or sexually, Heimlich said, "No."

Asked, then, if he's asserting that the girl repeatedly told a false story, he said, "Yes."

Asked if he wanted to explain further, Heimlich said, "Ah, no." But in a follow-up phone conversation he said, "I can't speak to the accusation because I would just be guessing and I don't want to do something like that. I don't know why it would've come up."

Yet Heimlich did plead guilty to one felony count of child molestation between February and December 2011, when he was 15 and the girl was six. The alternative? According to Heimlich, his lawyer advised that he faced a wrenching trial on two felony counts, with his niece placed on the witness stand. The lawyer listed on Heimlich's guilty plea, Steven Bobman, did not respond to repeated calls for comment. (The girl's mother says that Heimlich accepted the plea the day before her daughter was set to testify.) And if found guilty, Heimlich could possibly have faced at least 60 weeks in a juvenile rehabilitation institution.

As part of the plea agreement the first count, covering the interval when Luke was 13 and the child four, was dismissed. The court placed Heimlich on two years' probation; ordered that he register as a Level 1 sex offender (those considered the lowest possible risk to reoffend) and that he attend two years of biweekly sex offender counseling; barred him from using alcohol and recreational drugs and from going on the Internet unsupervised; and prohibited contact with his niece or any child born after February 1998. He was also required to write his niece a letter of apology. Do all that, he was advised, and after five years his criminal record would likely be sealed.

Asked last month the core question that any employer, teammate or neighbor going forward will ask—Why plead guilty to so heinous a crime, and write, "I admit that I had sexual contact with my niece," if it were not true?—Heimlich replied, evenly:

"I had several conversations with my mom, with my dad, and ultimately it came down to: We thought that this was going to be the best route for me and my family, knowing that it was basically a he-said/she-said. In the court of law we didn't really think I stood a fair chance; that was the advice we had been given. So we thought that pleading guilty was going to give me the best chance at a normal life, and our family a best chance at reconnecting and being able to just kind of move past this whole event."

The precise moments when he wrote his admission of guilt and signed his name, Heimlich says, were "definitely emotional. It wasn't easy for any of us. I definitely think at the time we didn't understand the magnitude of the situation, either." But he blames no one else for the decision.

"We didn't have all the answers, clearly," Heimlich says. "We didn't know what was going to happen. I would never say I was pushed into pleading guilty by either of my parents, because ultimately I can make decisions for myself—and I was the one that wrote my name down and pled guilty."

Throughout the judicial process, two words stuck in Heimlich's mind: five years. After that, he was sure, "This'll be like it never happened," he says. "It'll all be done... . So for those five years, or mainly the first two or three where I was in Washington and had to do more stuff on probation, it was, I just need to follow every rule to a T, and then when the five years come I'll be fine. I was not doing anything to go out of my way to talk to somebody or confront anybody. It was, just, What do I need to do? Tell me, I'll do it, and we'll be good."

Among experts on juvenile sex offenders, the disconnect between the two Lukes is not surprising. "Either the kid didn't do it or he did it and he's in some form of denial: Neither one is unusual," said Carolyn Frazier, a juvenile defense lawyer and assistant professor at Northwestern's School of Law. "To be innocent and plead guilty to something is not unusual." She then quoted a line from a national columnist's February condemnation of Heimlich and OSU: If you were absolutely innocent—as Heimlich contended—how many of you would plead guilty to felony child molestation simply to avoid trial? Thought so.

Frazier sighed. "That's another instance where, if you're a practitioner in this world, you're ripping your hair out," she said. "I'm, like, Dude, this happens all the time."

What happened next with Heimlich, though, was hardly common. Eight days after his plea he began classes at Puyallup High, transferring from out of district to play for its powerhouse program. Later, Vikings baseball coach Marc Wiese would say that he never knew of Heimlich's conviction or registered sex offender status. Luke assumed the school district and principal had been notified, but he wasn't required to personally disclose his status to teammates, teachers and coaches. So he didn't. The plan was to keep quiet, keep abiding by the agreement and keep counting down the days.

****

Time, now, for a gut check. We've reached the point in the narrative just before Heimlich blossoms into the pitcher coveted by D-I programs, before he became the sports story you don't want to read. He's just an obscure 16-year-old finding his way after 11 years of schooling at the kitchen table, a cipher to most kids brushing past in the halls of Puyallup High.

So, the question is: What is that Luke Heimlich, the mere statistic, just one of some 12,400 juvenile sex offenses in 2012, supposed to do? More to the point, what do you think he—that kid who just pleaded guilty to child molestation—should be allowed to do? Should he be allowed to play varsity sports while on probation, practice infield drills before sex offender counseling? Should all around him know of his crime and punishment? Or should he be prevented from putting on a school uniform, walled off from the skill-set that might prove crucial in reforming him into a responsible adult?

Wrestling with this, inevitably, leads to the concept of juvenile justice itself, which, in its purest form, contrasts starkly with the punitive impulse animating adult law. Practices vary from state to state, but in essence juvenile justice operates under the belief that childhood crime is different, that the still-forming adolescent brain doesn't fully know what it's doing, that shaping the offender's future—and thus society's, in the long run—is more important than exacting redress for the crime. Juvenile justice assumes that intervention and rehabilitation efforts can succeed, especially when the perpetrator is shielded from public—and media—attention that could undermine, forever, any hope for a fresh start.

That need for confidentiality is especially acute in sex offense cases, given the indelible nature of an accusation, let alone a guilty plea. With a headline like the New York Post's THE STAR OF COLLEGE BASEBALL'S BEST TEAM IS A CHILD MOLESTER, lodged forever online, a young man like Heimlich "can expect a lot of shame, a lot of hate and a lot of people who will never, ever, let him move past this," Frazier said.

Whether you're 15, 25 or 35, the case file is horrific.

But juvenile sex offenders present a vexing paradigm. In the popular mind their crime—especially one involving an age gap like Heimlich's—is singularly heinous and powered by an urge that can never be cured. Yet it's precisely in the area of sex offenses in which juvenile justice can seem most effective. A preponderance of studies, including pioneering work by Letourneau and Michael Caldwell, has found that the five-year recidivism rate for an offender like the first Luke—who pleaded guilty—is 2.75%. Research suggesting a low reoffense risk for first-time offenders who consistently deny guilt, the second Luke, is far less definitive. But, Letourneau said, "denial is normative," for juveniles facing sex-offender stigma, "and there's definitely no strong evidence that it influences reoffending rates."

Does this matter? A 97.25% success rate should weigh heavily in Heimlich's favor—though any parent with a kid approaching a former sex offender in an autograph line might find 2.75% a huge figure too. Over the next five years Heimlich would, by all accounts, check every box, attend every session and abide by every stipulation of his probation. He would show no sign of reoffending. The juvenile justice system—as well, perhaps, as a maturing teenage brain—would do its work almost perfectly.

Meanwhile, despite feeling guilt over the fact that his brother would not, and his niece could not, visit his family when he was at home, Heimlich was able to lock in come first pitch. At a moment when many sex offenders succumb to depression, self-loathing and a plummeting self-image, he began to be great.

Some saw it coming. Heimlich had long been athletically precocious: While in middle school he was a varsity pitcher at Rogers High. Though forced by transfer rules to play jayvee when he moved to Puyallup in 10th grade, he treated scrimmages that spring like championships, throwing 85 mph, slicing the strike zone, mowing down older classmates. "All business," says Wiese, the Pullayup coach. "He wanted to—how can I phrase it?—show those guys that he should've been a varsity guy."

Broad shoulders and long arms foretold plenty of upside, "but the big thing was his competitiveness: He felt he was better than anybody," Wiese said. Arizona started tracking Heimlich, invited him for a visit during the following summer; in December of his junior year—before Heimlich threw even one pitch of varsity baseball—Oregon State offered a scholarship. By then, between volunteering at his church and maintaining a 3.75 GPA, he was touching 87 and grooming a curveball.

In the spring of 2014, Heimlich went 11–0 with a 0.66 ERA , leading the 28–0 Vikings to the state title. When Beavers pitching coach Nate Yeskie called, just before the state semifinals, to ask Heimlich to reclassify, forgo his senior year and come to Corvallis, it made sense: Heimlich was 18 and had done all a high school pitcher could. He couldn't have been more ready.

****

Indeed, Heimlich's probation and court-ordered classes ended in June '14, and it didn't hurt that his leaving would clear the way for his brother and niece to visit Luke's parents at will. He still had three years remaining in the order to register as a felony sex offender in Washington—and by Oregon law was required to register there upon arrival—but by then he knew the drill. On Sept. 23, six days before classes began, he reported to the Corvallis Police Department and signed all necessary documents.

Seemingly, Heimlich, who lived off-campus, had fulfilled his duty: At the time Oregon State had no rule requiring enrolling off-campus students—or athletes with or without scholarships—to declare criminal felony convictions or, specifically, sex offenses. The state police maintains Oregon's sex registry. Once notified by local police that a student has registered as a sex offender, it follows a courtesy agreement with OSU to alert its Department of Public Safety. In Heimlich's case such information would filter to select athletic department personnel.

"As far as what I needed to do, I needed to tell Benton County and then they send the information to the university," Heimlich said. "And that's what happened."

Not quite. Because of what state police spokesman Tim Fox calls, "essentially, a clerical error" by both the state police and the Corvallis PD, and a series of unreturned phone calls and mail notifications that were marked undeliverable, 18 months passed before Oregon state police first notified the university of Heimlich's sex offender status. Corvallis PD failed to fingerprint Heimlich when he first appeared, Fox says, and without positive identification Oregon state police could not add him to its sex offender registry.

Fox says the onus for correcting the "error" lay with Oregon state police, not Heimlich: "His requirement is to register, and he had done that."

After two more calls from Oregon state police in the winter of 2015–16, Heimlich had his prints taken on Feb. 11 at the Benton County Sheriff's office in Corvallis. On March 16, 2016—midway through the second semester of his sophomore year—state police emailed Chuck Yutzie in the university's Department of Public Safety to inform him that Heimlich was on the state's sex offender registry. What Yutzie did with the information is unclear; he didn't reply to SI's request for comment. Heimlich believed the university knew his status since his matriculation, but he says he never fully discussed it with Pat Casey until shortly before The Oregonian story broke last June. (The coach deferred questions on the matter to university officials, who declined to answer on the basis of student privacy restrictions.)

When asked, in April, if he felt blindsided by Heimlich's sex offender revelation last June, if only because he had assumed the job just seven months earlier, Oregon State athletic director Scott Barnes said, "In that regard, yes, because we didn't know anything about it. So it was a surprise, for sure." (According to police figures cited by Oregon State spokesman Steve Clark, there are 11 registered sex offenders currently enrolled on campus. On Feb. 15 the university announced a new rule requiring all enrolling students to self-report felony convictions and disclose whether they are registered sex offenders.)

Before that Oregonian story, any ink Heimlich received in 2017 centered on his near monotonous dominance. After two years of shuttling in and out of the rotation, he had spent a summer adding strength and endurance; his curveball had picked up a savage bite, and he mastered a slider. In the '17 opener, he struck out 11 in 5 2⁄3 innings—and then got better; by the time Heimlich carved up Stanford in a four-hit complete game on March 31, his record stood at 5–0 with a 0.52 ERA and a fastball clocked at 94. Every scout in town wanted to chat.

Three days later, at 2:20 p.m. on a Monday, a Benton County sheriff's sergeant issued Heimlich a citation at the OSU baseball office in Gill Coliseum for failure to register as a sex offender. "I was mainly confused," he says. Heimlich had notified authorities each time he had moved: "I thought I did everything right."

After calling his parents and retaining a lawyer, Heimlich learned that he was being charged for failing as an Oregon resident to register within 10 days of his last birthday. Problem was, Heimlich was still a Washington resident, and operating by its requirements. The charge seemed a question of crossed wires, easily disposed of. He struck out eight in his next start, a win over Utah, and even felt the smallest sign of a thaw from his brother, the father of his niece.

On April 13 the Beavers traveled to play Washington in Seattle. The two men still weren't speaking. Luke never picked up his face in the crowd but says he knew, while pitching, that his brother was in the stands. Asked if it made him feel better or worse, Heimlich went quiet for four seconds, the only moment in an 84-minute interview when he lacked a ready answer. "There's thousands of fans at the game, I can't really control what ... ." he said at last, and then stopped and stared.

But this is your brother, Heimlich was reminded, and in the most loaded of circumstances: Did it matter that he was there?

"Yeah," he said, voice gone flat.

Heimlich gave up three runs and struck out seven that night in Seattle, his only loss of the year. On May 17 he appeared in a Benton County courtroom, and the April citation was dismissed because of "insufficient evidence of Defendant's knowledge of Oregon reporting requirements." He felt pretty sure he was going to be all right.

On May 18, 26-year-old Danny Moran, the Oregon State beat writer for The Oregonian, sat in his Portland apartment and typed "Luke Heimlich" into an Oregon public records database. The newsroom has long stressed background checks on feature subjects, and not only because the ice cream vendor in a 1993 puffball piece ended up being a former sex offender. Editors call it the "no surprises" rule. Moran hit enter.

It was supposed to be a standard player profile, a lead-up to Oregon State's postseason via its ace. A page opened. There, in a box on the right side of the screen, four key words popped: failure report sex offender.

"I didn't believe it was him," Moran said. "I thought there had to be another Luke Heimlich."

Moran checked the birthday, the middle name.

It was his second year covering the Beavers, a big step up after 20 months of grinding out high school coverage. Now Moran dialed his editor, gut fluttering, but struck by a very unjournalistic idea: how much easier life would be if he just hadn't found it.

He was still a bit young to know. Sometimes the stories find you.

****

On Thursday, June 1, 2017, with the No. 1 Oregon State Beavers preparing to host a four-team NCAA tournament regional in Corvallis, Heimlich addressed his teammates. Walking into the locker room at Goss Stadium, the Beavers, 49–4, had never been so deep or so strong, not even when seizing national titles in '06 and '07. The previous year's NCAA snub had them angry. A 16-game winning streak had them primed. Now came a crowbar to the knees.

This was just before practice. In describing it, Heimlich didn't say whether he addressed the team as a whole, or individually, or both, but he makes clear that he didn't present himself as the Luke that wrote of "sexual contact." This was the second Luke, innocent Luke, before his toughest audience yet: A roomful of young alpha men who'd been steeping for years in macho jock culture.

The reason: He wanted them to hear it from him, first. The Oregonian story was coming.

Eleven days earlier, after tripping over Heimlich's name online, Moran began making calls. A source at a county DA's office sketched the basics: Heimlich had been 15, the victim aged "12 and younger." A news researcher informed him that Washington state doesn't automatically seal juvenile records for certain crimes. The Pierce County records office agreed to send the Heimlich case file, but only by mail, and after receiving a money order.

The story went on hold. Heimlich, that week, needed only 88 pitches over eight innings to shut out Abilene Christian and raise his record to 10–1; for the season he would surrender just four extra-base hits and no home runs. "He's a rare find, just above and beyond what most college pitchers are," says Abilene Christian coach Britt Bonneau. "He has four pitches? That means he has eight, because he can double those four because of his location.

"I mean, they win the national championship last year if he's still pitching for 'em. No doubt about it."

On May 30 the case file arrived at The Oregonian offices: more than 70 pages, one containing Heimlich's handwritten admission. By noon of June 1, Moran had been on the phone with university officials and sensed that they knew what he had. That day Luke spoke to his teammates of the citation that had sent him into court, his sex offender record, his reasons for pleading guilty, "and I kind of told them the background and I told them that I had denied it," he says.

"They received it well," Heimlich said. "I lived with seven, eight other guys on the team last year in a house, and all of them checked on me, I think, that day at practice when we were out shagging BP, or doing fielding drills. I think almost everybody on the team kind of came up and gave me a hug or said they supported me." Pat Casey's eyes well and his voice grows hoarse in recalling the scene. "I thought that ... " he says, then stops. "I thought that the team, really, you know ... embraced him at that time. And really wanted to help, at that time."

And now? The Beavers' feelings remain nearly unknown; Oregon State turned down repeated SI inquiries to speak to any player on the 2018 roster about Heimlich, and aside from second baseman Nick Madrigal's quote in the Tribune on April 21 ("Everyone has pulled for him through all he has gone through. He's a great teammate. He's an even better person than he is a pitcher"), the team has said nothing about its ace's troubles.

The day after Heimlich's in-house revelation, Oregon State crushed Holy Cross in the regional opener. The next day Heimlich two-hit Yale over seven innings. "When David Price came to the big leagues out of Vanderbilt and was put in the Rays' bullpen? Heimlich could do the same," says Stuper, who won 32 games in the majors, including a complete-game World Series win for the 1982 champion Cardinals. "I'm not a scout, but I pitched. He could get big league hitters out. No question in my mind. Zero."

Five days later The Oregonian story dropped. Critics bashed the timing, the undermining of juvenile justice, the derailing of a kid who had seemingly reformed. Casey declared, "I believe in Luke." Moran received death threats, a series of emails culminating with an OSU professor telling him to "go f--- yourself." Top editor Mark Katches cites competitiveness, public safety and the surfacing of a criminal record of a public figure as factors in his decision to run the piece. "Whether you're 15 or 25 or 55, the case file is horrific," he says. "And that was the ultimate determining factor for us. This was of such gravity that it didn't feel like it was remotely right to think about doing anything else other than publishing the story."

In a statement released through his lawyer, Heimlich announced his immediate withdrawal from the team. It read more like the first Luke, guilty and penitent: "I have taken responsibility for my conduct when I was a teenager. As a 16-year-old I was placed on juvenile court probation and ordered to participate in an individual counseling program. I'm grateful for the counseling I received, and since then, I realized that the only way forward was to work each day on becoming the best person, community member and student I can possibly be. I understand that many people now see me differently, but I hope that I can eventually be judged for the person I am today."

Six days later Heimlich's statement announcing his withdrawal from the College World Series began: "For the past six years, I have done everything in my power to demonstrate that I am someone my family and my community can be proud of, and show the one person who has suffered the most that I am committed to living a life of integrity." He went on to mention "turmoil for my family,"and a fear of directing "even more unwanted attention to an innocent young girl."

Maybe it's worth noting that Heimlich, at that time, was still 10 weeks short of his five years, the August 2017 date when his juvenile record could be sealed and his sex offender status lifted. Maybe innocent Luke had been feigning official guilt for so long that he thought he should finish out the job. But sorting through such dissonance, trying to reconcile the first and second Lukes, seems a task beyond the powers of your average major league team.

Heimlich, a top 50 prospect last season, says he has been interviewed by many scouts in 2018, and is "confident that I'll have the chance at professional baseball after this year." Casey not only thinks he'll be selected in this year's amateur draft, which begins on June 4, but will be also picked "around where his ability lies"—the late first or second round. To do that a team would be taking into account the 50-50 chance that a college pitcher will even make the majors; the uncertain impact that a sex offender could have on clubhouse and fan morale; and the possibly conflicted feelings of not just the club's own front office but also every small-town affiliate that Heimlich might pass through in the minors.

Last year, given only four days to process The Oregonian story, every team passed. He could have signed with an organization last summer as a free agent; no offers came. For at least one major league general manager, who considers Heimlich, "real, high-end talent," nothing has changed. "I don't know anything about him other than the story," he said. "But my scouting director asked me then and he's asked me again this year and I said, 'Don't scout him. Do not waste your time, because we're not going to take a chance on this situation.' Because from a public-relations standpoint, I don't know how to handle it.

"And I did give it some thought, because I do wrestle with, Well, people can make mistakes at a young age ... But how do you somehow decide to put your entire franchise behind this, and think you're going to survive the hurricane of negativity that's going to blow? I feel for the kid because, allegedly whatever occurred, he's gotten in the treatment programs and moved on with his life and gotten to this level. Hey, congrats. But that doesn't mean that we—or any of the 29 other clubs—have to participate in that process and hire him."

****

Yet, even knowing all this, it's hard to take your eye off the ball. The flash of a line drive, the mini-drama of each at bat, the seductive sight of excellence: All of it combines at a baseball game to arrest the mind. Mix in the emotions of a 124-year-old blood feud, and it's easy to see how, if just for a few minutes at a time, fans at Goss Stadium could watch Luke Heimlich take Oregon apart in April, and revel in it.

"Dude, it's the Civil War," alum Travis Terrall said in the bottom of the sixth. "I didn't even know if he was pitching tonight." Terrall stressed that he's "accepted," if not forgiven, Heimlich's presence on the roster, and admitted the rationale involved is disquieting. Because if Luke Heimlich, Sex Offender, were wearing an Oregon uniform, he said, "it'd be so easy to hate him, then."

That such simplification is childish—and central to sports' appeal—is precisely what makes it so dangerous. "Seventy-five percent of all women in drug and alcohol treatment have been sexually abused," says Brenda Tracy. "Seventy-three percent of all people receiving gastric bypass surgery for obesity have been sexually abused. The consequences of sexual abuse are huge—and we're not talking about it.

"Or if we are, it's in the context of a sports story like Luke Heimlich, and we're saying it's a mistake and it's O.K., and we're rationalizing it because we want him to play baseball: To entertain us. Luke is probably a great kid. But right now? As a country we cannot continue to have these people in positions of influence—influencing our children, influencing the dialogue, influencing the narrative that we have around sexual assault and sexual abuse. Because we're minimizing it. And we're not even thinking about the victim."

What about that little girl?

According to her mother, she's doing well these days. She has little memory of what happened when she was four to six years old, and seemingly no lingering effect has surfaced—"she just knows that [Luke] was inappropriate," the mother says. "But those kind of things manifest differently in every single victim. As far as I can tell, no, it hasn't. She's still my superstar girl; she's stronger than most full-grown women. I mean, she's great. But I do worry that in the future that it will."

Gorchels, the OSU season-ticket holder, didn't recall her abuse until a health class in middle school triggered the memory. But even before then, she says, she grew up wary of physical contact, suspicious of anyone bigger. Relationships, her ability to trust potential suitors and mentors, suffered. A bid at intimacy at Wellesley triggered full engagement with what happened when young, and it took years to regain her balance. She has a boyfriend now, and finds it notable that he's short. "I'm 5' 4", same height," Gorchels said. "So I don't feel threatened."

Though Gorchels believes he should not be allowed to pitch, it's not as if she doesn't hear the other side. Her brother and father, who bought her OSU season tickets, wonder aloud about juvenile brains and the value of second chances. "Even my own family has expressed that he should be forgiven and it should be fine," Gorchels said. "It really frustrates me." But her dynamic shows that there doesn't have to be an either/or conclusion.

"People say, 'Well, what about the victim? The victim's feeling terrible,' " Frazier says. "I get it, but we need to stop doing [just] that. Nobody is saying that the victim shouldn't be thought about. Hopefully the court process has taken care of them; hopefully, it's held the young person accountable for what they've done. But it's O.K. for us to ask, 'How do we think about a sexual offender who has been moving on?' It's O.K. to care about that kid too."

According to Fox, Oregon has yet to grant Heimlich relief from registering, and he must still notify authorities whenever he moves. But, in the state of Washington, where his rehabilitation was judged a success and his juvenile record was sealed last Aug. 28, Heimlich can live and work as a normal citizen with no restrictions. He can have contact with children and engage his family, though tensions linger. "Honest, I would advise everyone to keep their little girls away from him," said the niece's mother. "And I would still keep my little girls away from him." Luke still has not spoken with his niece, though they've seen each other a few times at family gatherings. As far as repairing the fraught relations with his niece's father, his brother, "that's still a work in progress," Luke says. "It'll happen. It just takes time."

Clearly, the relationship with Oregon State has progressed a bit further. At 8:37 p.m., with one out in the eighth and OSU leading Oregon 5–2, Heimlich gave up only his fourth hit, and Yeskie strolled out to the mound and took the ball. The crowd, seemingly all of it, gave Heimlich a standing ovation and roared louder at the announcement that with his 12 strikeouts tonight—and 305 total—he had become the school's career strikeout king.

"LUKE!" a voice in the stands cried, as Heimlich walked off, smiling tightly. No one mentioned then, or in the ensuing days, that it never should have come to this; the record was Heimlich's only because no MLB team wanted him last year. "LUUUUUKE!" another voice chimed in, then another. The applause kept rolling. The stadium deejay cranked up, "Welcome to the Jungle."

So maybe all those voices, all the insiders insisting that Heimlich will never be drafted, are wrong. Maybe some major league GM has been watching him mow down hitters in Corvallis this spring and heard that catcalls on the road have been few. Perhaps there's been just enough uncertainty thrown into the air surrounding what happened at that house on the edge of Puyallup, the one with the Oregon State flag flying on the porch.

This is an age of Too Much Information, sure, but that complaint is less about quantity than it is about kind. We absorb the once appalling with an ease once unimaginable; "normal" changes by the day. So here's a good time to mark our capacity. Maybe we should know how much we're ready to take—be it out of compassion or callousness or the urge to be amused. Because if some team drafts Luke Heimlich, you will hear them clear. One voice asking why we shouldn't forgive. And another one asking if we'll forgive most anything.