How Mississippi State Baseball Turned a Season That Began in Humiliation Into a Trip to Omaha

STARKVILLE, Miss. — The nameplate is gone.

Someone stripped it off the door months ago, torn from the smooth wood, execution style, in a dismantling of the final reminder of a most humiliating moment in the illustrious history of Mississippi State’s baseball program.

Remnants of its existence, like the man himself, remain: a rectangular-shaped white discoloration centered on the door of the head coach’s office, splotches of dried adhesive and, to those attentive enough, shadows of letters now lost: ANDY CANNIZARO.

No one, not even interim head coach Gary Henderson, has moved into that office. Staff members only enter the room to adjust the building’s thermostat, housed on the office’s interior wall.

“Bad juju,” says one member of the team, “in there.”

The improbable start to Mississippi State’s 2018 baseball season—the forced resignation of its second-year head coach following the opening weekend—is only outdone by its remarkable end: a trip to the College World Series.

This is no small feat. In fact, the NCAA says it has no record of a team with an interim coach advancing to the CWS. Just half of the NCAA tournament’s top eight seeds made it to the pinnacle of the sport in Omaha, Neb. Teams seeded second, fourth, seventh and eighth are no longer playing.

The Bulldogs, interim coach and all, are. How? They swept top-ranked Florida in the final regular season series to leap off the NCAA tournament bubble, they got two postseason, walk-off home runs from junior right fielder Elijah MacNamee and they out-lasted host Vanderbilt in an 11-inning, winner-take-all super regional game.

“It’s unbelievable,” Henderson says.

College World Series Preview: Power Ranking the National Title Contenders

On a sun-splashed Tuesday, team members are packing equipment and luggage onto a bus, bound for college baseball’s holy land. They only achieved such triumph after their young, bubbly and extroverted head coach was pushed out 479 days after his hire.

The reasons behind Andy Cannizaro’s bizarre end go well beyond the one publicized at the time of his ouster: an extramarital affair with a Mississippi State employee.

Those close to the program describe a 39-year-old man, overwhelmed with the job, who developed an obsession: his phone. They point to his stream of boastful posts on Twitter: a muscle-bound Cannizaro lifting in the school’s weight room.

Can a man’s fall from grace really center around him texting and tweeting? Those here say it was a significant part of a disconnect that grew between he and everyone else within the program. Some describe it as a phobia that resulted in disorganization, a sloppy team whose players admit that they were neither ready nor prepared for the season.

The case against Cannizaro mounted, and rumblings from those on and around the team trickled to athletic director and former baseball coach John Cohen. Things came to fruition after that first weekend—an 0–3 outing in a three-game series at Southern Miss—when disturbing details from the dugout emerged: a head coach buried in his phone while his squad played a game 15 feet away.

A person close to Cannizaro defended the coach on the accusations: “There are two sides to every story,” the person said. Cannizaro, a burly former eight-year professional player, politely declined comment in a text message. He hasn’t necessarily gone into hiding. He remains in Starkville. In fact, residents spot him around the town often—at the gym, a restaurant, a stop sign.

In a telling truth, staff members and players say no one has spoken to Cannizaro since his departure. The same goes for Cohen, the man who, after being elevated to athletic director, hired Cannizaro to replace him in November 2016.

“It was a very unfortunate situation that happened,” Cohen says. “The more I learned the more I felt it was more and more unfortunate.”

Mississippi State administrators, players and coaches declined comment on details of Cannizaro’s time here—still a touchy subject.

Cannizaro’s departure brought what assistant Jake Gautreau called a “new season.” Players were “all in immediately,” he says from within his office, two doors down from where Cannizaro once worked.

“You think you might lose the club or get some resentment or kick back. Not at all. They were excited,” says Gautreau, a one-time close friend to Cannizaro who played college ball with him at Tulane.

Jake Mangum, the team’s go-to leader and ultra-competitive centerfielder, describes the team’s reaction to the Cannizaro news in another telling bit: “We heard all the rumors for a while. We’d known for a while. Then it went public. When it happened, we were like, ‘Let’s go!’”

“You could see it,” assistant Mike Brown says. “You could see he was going through some issues. He got trapped in something we on staff couldn’t really relate to. There was a disconnection.”

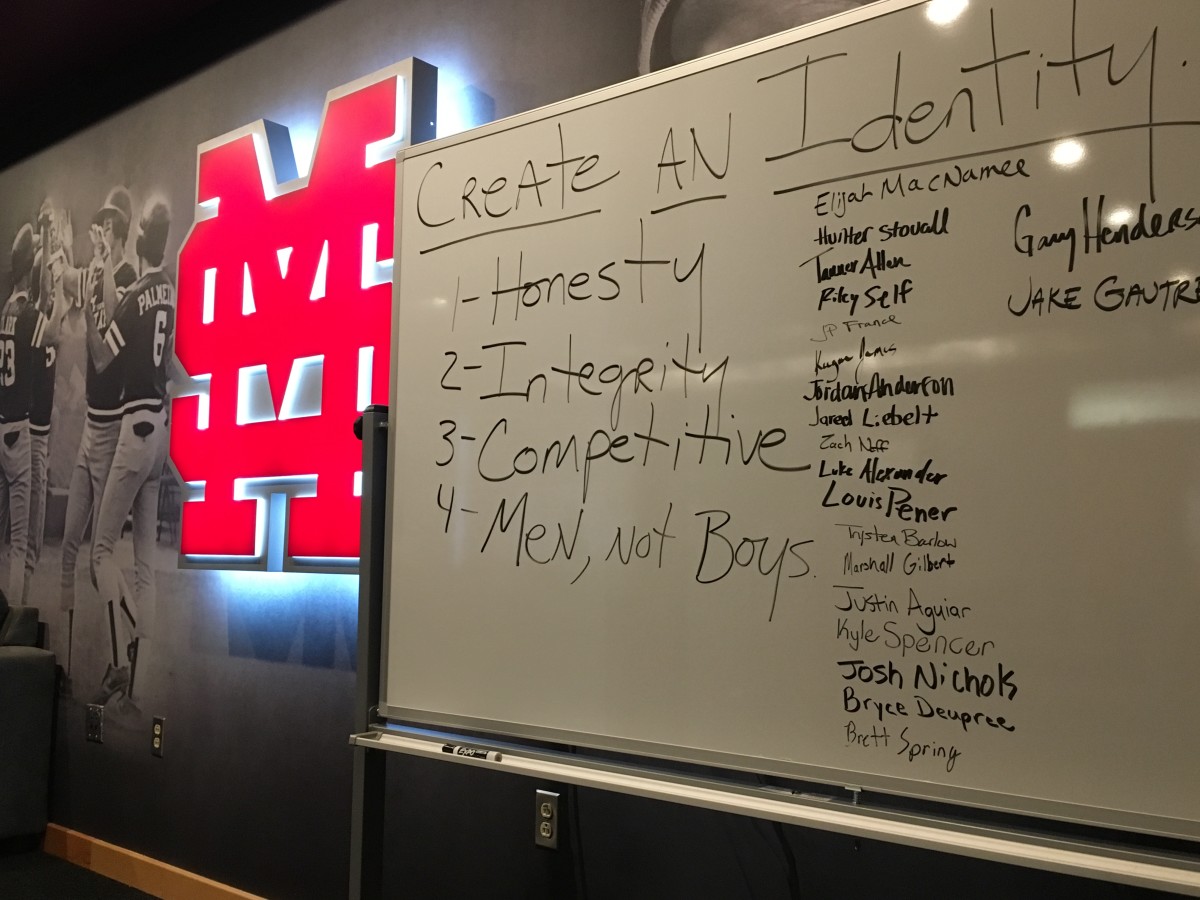

In Mississippi State’s Hall of Fame room, evidence of the first step in the Bulldogs’ new season still exists.

The words on the white dry-erase board are four months old, scribbled in black marker the day after Cannizaro lost his job. “Create An Identity,” it reads, before four bullet points: 1) Honesty, 2) Integrity, 3) Competitive, 4) Men, not boys.

Each player and staff member signed their name to the board, every signature still there some 100 days later. Henderson met with his new team before the start of his impromptu head coaching stint began with a 12-day, eight-game road trip.

“That morning we met and I knew it was going to be the most important 20 minutes of the season,” Henderson says. “We had to move past the humiliation.”

Explaining how this team—one that started the year 14–15 and 2–7 in the league—is in Omaha readying to play Washington in the primetime slot Saturday night at the College World Series is not easy. But it starts with a staff of coaches who have not only grown accustomed to change but have thrived in it: Henderson, Gautreau and Brown.

In two years in Starkville, Brown and Henderson are working for their third boss. Cohen hired Brown as a volunteer coach and Henderson as pitching coach about four months before he moved to athletic director.

“It’s been a time of a lot of change,” Henderson says.

You don’t have to remind the players.

“Three years. Three head coaches. Three Super Regionals,” Mangum says. “We finally won one.”

The path to that Super Regional victory was laid weeks prior. Some say the turning point for this squad was a series win over then-No. 3-ranked Ole Miss in early April. Others claim it’s that 12-day road trip in late February.

Brown points to the coaching change.

“Once the decision from the top came down, I think that was the difference,” said Brown, a California native who worked for Henderson at Kentucky. “We were freed up, able to teach, able to motivate and implement strategies.”

Gautreau and Brown took over the offensive duties, previously handled by Cannizaro. How’d the offensive approach change?

“We didn’t have an approach before,” Mangum says flatly.

This is not necessarily a rags-to-riches tale—more of a down-but-not-out story.

Mississippi State has talent. Mangum, for instance, was the Southeastern Conference’s Freshman of the Year in 2016 and hit .324 with a broken hand last season. The team’s lefty starting pitcher, Konnor Pilkington, was selected 81st in last week's MLB draft, one of seven Bulldogs taken. Also, State began this season ranked 12th nationally by D1baseball.com.

The program has history. It has advanced to Omaha more times than all but 14 other programs, and the school’s Major League alums are a who's who: Rafael Palmiero, Jeff Brantley, Will Clark, Kendall Graveman and Jonathan Papelbon.

The school annually out-draws in attendance all but a handful of others, and MSU is currently on Year 2 of a two-year, $55 million renovation to its ballpark, Dudy Noble Field. It will seat about 13,000 people, or slightly half of the population of the north Mississippi town in which it resides.

Starkville is without a mall, but that’s not the biggest gripe from new residents to this place. There is, gasp, no Target.

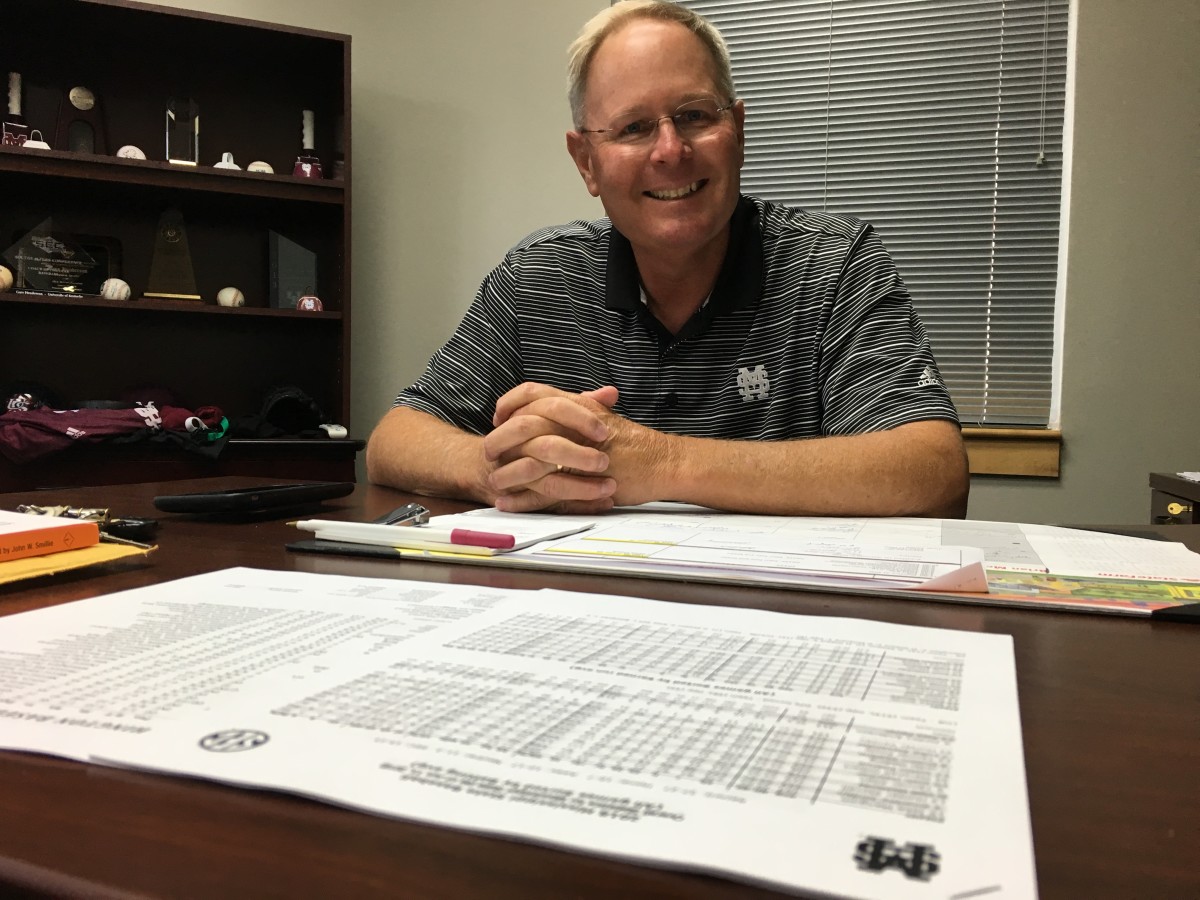

Henderson seems not to care about such things. He’s in no rush to leave. He wants the full-time coaching job.

“We love this place and we want to stay,” he says with authority, “and I want my staff to stay.”

Henderson is referred to in the building as “Coach Hendoo.” He’s a 55-year-old pitching guru with a dry sense of humor, filled with witty wise cracks that sometimes have reporters chuckling. He made his mark as an assistant at Florida and then Oregon State before Cohen hired him to tutor his pitchers at Kentucky. He replaced Cohen as head man at UK in 2008. Eight years and 258 wins later, Henderson resigned after missing the NCAA tournament for a third time in four seasons.

In nearly a decade in Lexington, he won four NCAA tournament games. This year, he’s won six, all on the road, and two of them in a single day on the way to downing national seed Florida State on its own field during regional play.

His Bulldogs are 5–0 in NCAA elimination games.

“I have let Gary run the baseball program,” Cohen says. “I knew putting ‘interim’ in front of ‘coach,’ … it’s really hard. I knew he could handle that. I believe in him as much as I did 10 years ago at Kentucky.”

The next head baseball coach at Mississippi State is not decided, Cohen says. He has trimmed a list of 20-plus candidates to about a half-dozen. He continues to interview coaches, and he won’t make a decision until after Mississippi State’s season is complete.

Henderson and Cohen met about two weeks ago to discuss the job. Cohen declines to reveal details of their conversation. Says Henderson, “it went great.”

It’s a weird time for everyone.

“We’re in a situation that neither one of us created,” Cohen says.

The coaches and their families head to Omaha in a peculiar position for College World Series participants: potentially out of a job when they return. Brown has two children, age 4 and 10 months. Henderson, on the last year of his contract, has a son two years away from graduating high school. Gautreau’s two sons are under age 5.

“My wife wanted to know the end result for us on Monday night (Feb. 19),” Gautreau says, referring to the Cannizaro change. “I told her I didn’t know. And I still don’t know.”

The coaching change was just one obstacle this year. State routinely starts four to five freshmen in its lineup, and it played the least amount of home games this season (23) than it has in a half a century. Because of the stadium overhaul, its first 11 games were on the road and it did not practice outdoors in the fall.

“We had to wear hard hats on the walk to our own dugout in preseason,” Mangum says.

Construction continues. Reaching the stadium from the baseball offices is a circuitous route that takes you in one door and then out of another in State’s indoor football facility, down a steep, unleveled sidewalk and through a dusty, graveled-covered work site.

On the route, Henderson skirts bulldozers and other bulky construction vehicles. A man hangs out of the cockpit of one, extending his fist to meet Henderson’s balled hand.

“Go State!” the man yells.

“They tell me there’s 24 engineers working the site and 23 of them graduated from Mississippi State,” Henderson chuckles.

Under Henderson, State is 37–24, has 20 come-from-behind victories and three series wins over top-five teams. How? Love, he says.

“There were so many avenues for them to get distracted. You got to be consistent with the message,” Henderson says. “It’s absolutely important to get players to love each other. Two days don’t go by that they don’t hear from me, ‘You’ve got to be a great teammate.’”

There’s a little luck, too, and a silly superstition.

For this team, that’s a banana, something that began in the NCAA regional final against Oklahoma. Freshman infielder Jordan Westburg grew hungry in the second inning, pulled a banana out of his bag and, for whatever reason, placed it atop his head. The Bulldogs scored eight runs the next inning and, wouldn’t you know it, Starkville has now gone bananas.

Giant, yellow inflatable bananas hang in one bar near campus, and one downtown Starkville watering hole threw a banana split party last week. In the dugout, bananas are as prevalent as bats.

“The banana is a telephone, a radar gun, in their belts like a pistol,” Gautreau laughs.

The fruit aptly sums up this season—it’s bananas, from Cannizaro to the College World Series.

Mississippi State is making its 10th appearance in Omaha. It has never won it all. In fact, none of the school’s 14 NCAA-sanctioned team sports can claim a national championship. The Bulldogs have been close.

In 2013, a Cohen-led State team lost to UCLA in the CWS championship series. Less than three months ago, coach Vic Schaefer and the women’s basketball team lost on a buzzer beater in the national championship game—a second consecutive national runner-up finish.

“Starkville deserves a national championship,” Mangum says.

It would be such a celebratory final chapter of a story that opened with a flop.

Those in the college baseball world—a niche community—praised Cohen for his hiring of Cannizaro some 18 months ago. Sure, he took a risk. A New York Yankees scout after his retirement, Cannizaro had been a college coach for just two years, LSU coach Paul Mainieri having hired him in 2014 to be his hitting coach and recruiting coordinator.

A vivacious, energetic man, Cannizaro took the Mississippi State baseball world by storm, winning over a rabid fan base with his outgoing ways and social media prowess. Anchored by big slugger and first-round pick Brent Rooker, Cannizaro’s first team surprisingly advanced to the super regional round and won 40 games.

They loved him until the very end. A headline from a story posted on SBNation’s fan-led Mississippi State website, For Whom the Cowbell Tolls, is proof.

“I Would Fight And Die In The Trenches With Andy Cannizaro,” the headline read. “Despite being swept this past weekend, Andy Cannizaro is the right man for the job.”

A day later, he was no longer the coach.

Asked if he regretted the hire, Cohen says, “I’m somebody who second guesses myself to death in everything I do. I try to dissect everything. I feel like it was a good process. I feel like the hiring of Andy Cannizaro was the right thing to do at that time.”

Cohen called the split “incredibly difficult.”

“There’s definitely an initial shock,” says Gautreau, a sports agent for the last few years before Cannizaro hired him last June. “You look at it as we had a coach with everything in front of him, best college baseball program in the nation. You were proud of him and proud of the opportunity. Looking back, how could you not take advantage of this opportunity and be here as long as you can?”

Henderson is hoping to be here for good. There is one last goal for him to accomplish, though, before Cohen makes his decision: winning it all.

Can this team really do it?

Henderson smiles before telling a story. The coach appeared for an interview Tuesday morning on a television show. In the background, the 2015 college football game between Michigan and Michigan State played. Henderson listened intently as broadcasters called the wild few seconds. Michigan led 23–21 with 10 seconds left before the Spartans blocked a punt and returned it for the game-winning score as time expired in what many call the wildest ending to a college football game.

“All they had to do was punt,” Henderson says. “One more reminder: Anything can happen.”