Tamed Fury: How Kirk Gibson Learned to Quell His Volcanic Ferocity After Years of Rage

This story appears in the July 16, 2018, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

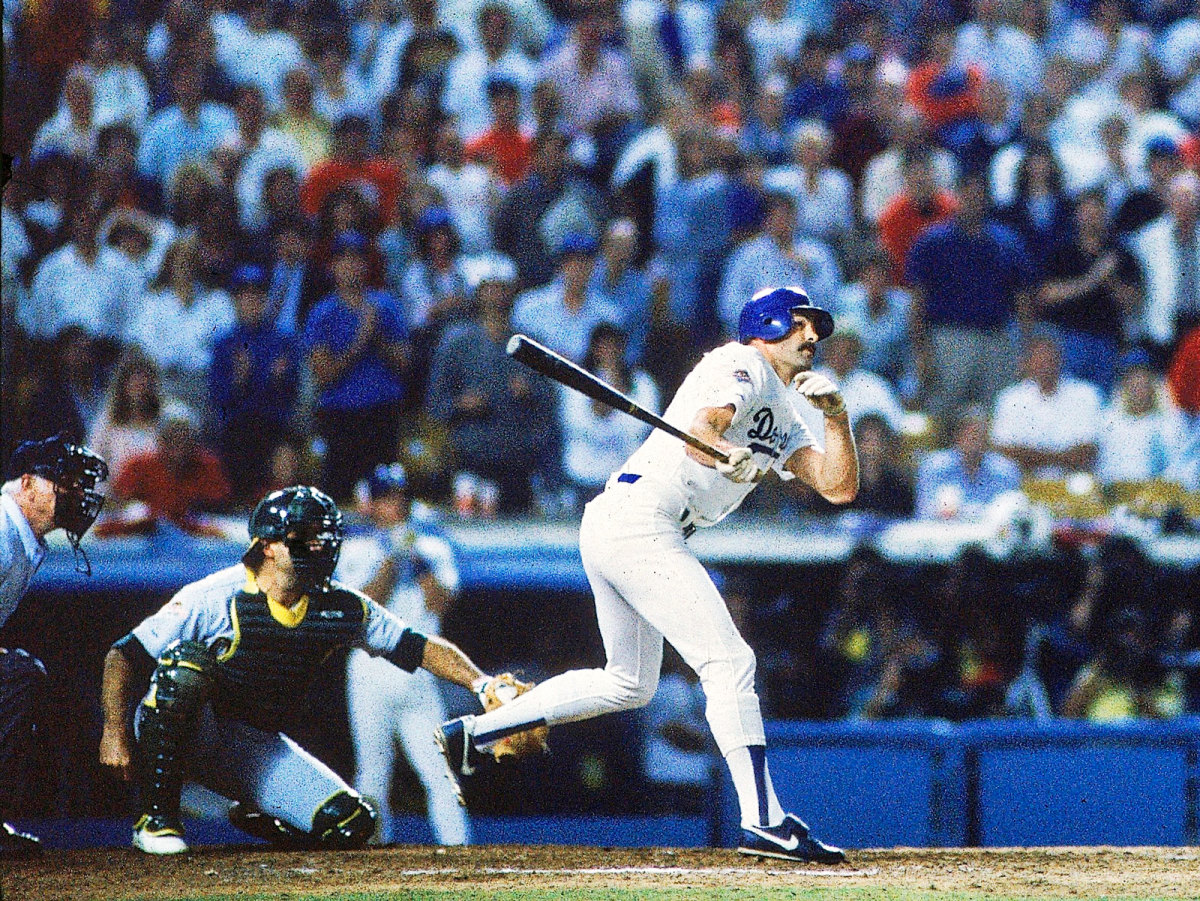

The first time I saw Kirk Gibson in the flesh, he was rampaging toward me, near-naked and jeering; the second time, he limped to the plate and hit one of the most dramatic home runs in history. One moment was heinous, the other heroic. In each he seemed unbound by humanity’s usual norms and limits, bigger than life, incomprehensible. Both events occurred three decades ago. Now it was a late-March morning in 2018, and as I approached a dugout, I recognized the broad back of Gibson, sitting alone.

This was at a practice field in the Detroit Tigers’ spring training complex in Lakeland, Fla. A coach throwing batting practice grunted, an equipment cart clattered: Gibson waited for his youngest son to take his cuts. A passing staffer, startled by the famous face staring out at the field, stopped long enough to venture a polite, “How you doin’?”

“Oh,” Gibson said warmly, arms opening wide, “just listening to the sounds of baseball.”

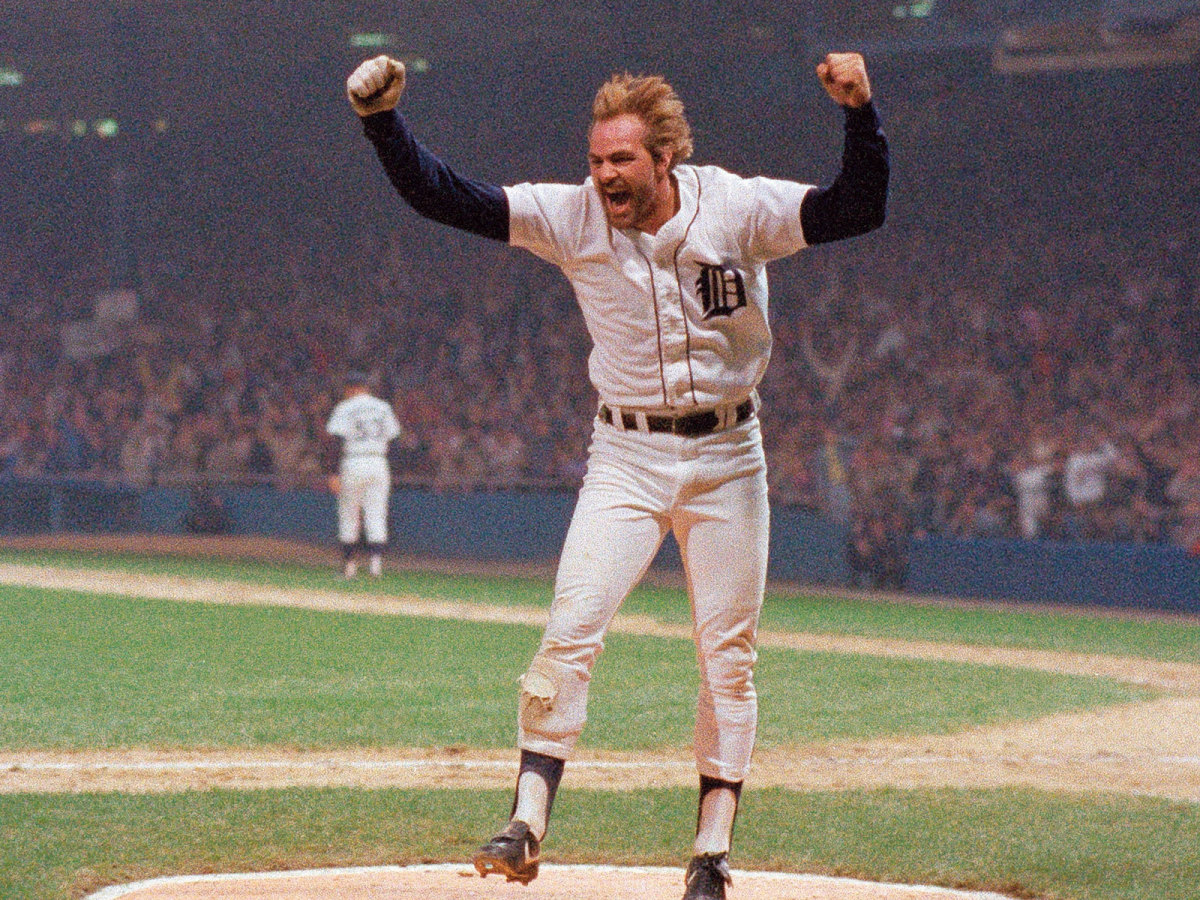

That was my first direct proof that, maybe, the man’s jagged edges had worn smooth. The sounds of baseball? In his prime with the Tigers and the Dodgers, in the 1980s, Gibson was hardly your Let’s play two! romantic; his vibe was about as pastoral as a punch in the face. He smashed titanic home runs. He ran the bases like a mustang. Shrewd, profane, honest and cruel, he leveled any opponent, umpire, teammate or, yes, manager fool enough to get in his way. -Tigers catcher Lance Parrish once described Gibson in the clubhouse as “a caged animal.” Detroit owner Tom Monaghan, miffed by Gibson’s unkempt Viking look, bid his one-time ALCS MVP good riddance in ’88 by declaring him “a disgrace to the Tiger uniform.”

In other words, you couldn’t take your eyes off Kirk Gibson. In other words, they increasingly miss his like in Motown and in L.A.—where, snarling at the steepest of odds, he delivered the signature blow in each city’s last triumphant World Series run. Yes, three decades have passed; nothing remains the same. Why should he? I had heard about Gibson’s calmer demeanor first as a coach with the Diamondbacks and then as their manager, about his 2015 diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease and the endearing way he calls his new opponent Parky. I’d read sympathetic takes on his ongoing—though reduced—performance as a color analyst on TV, seen the startlingly sweet graduation speech he gave at Michigan State in May 2017, weeks before turning 60.

“Remain humble, and always treat others with kindness and respect,” a berobed Gibson advised the crowd at his alma mater. “A harsh comment can hurt another person, but a kind word can produce amazing things.”

Amazing, all right. To hear Mr. Rogers pieties trip from the mouth that once dumped f-bomb abuse on reporters and autograph seekers won’t ever lose its novelty, but the world has taken note of Gibson’s olive branch and returned it in kind. He got an honorary doctorate and cheers on that East Lansing stage and, after a 39-year wait, was inducted last December into the College Football Hall of Fame. If not the metamorphosis of his fellow 1980s celebs—Trump? Schwarzenegger?—it’s a second act unmatched by the rest of that era’s baseball churls.

Part of this recalibration, of course, stems from the $13.5 million that Gibson has raised for Michigan State and the more than $2 million for Parkinson’s research. Part arises from the sympathy sparked anytime someone struggles publicly with a disease. But part also lies in what the disease has done to him -specifically: Parky, an incurable, progressive brain disorder that attacks motor function, has made Kirk Gibson smaller.

I noticed this instantly in Tigertown. Left arm wedged close to his side, head slightly ducked, Gibson now takes up less space than a 6' 3", 220-pound alpha male ever should. I saw it more clearly a few weeks later, when he appeared at Dodger Stadium on Opening Day for a 30th-anniversary- celebration of his epic World Series home run. The waiting media didn’t know what to expect; one radio hand recounted being scorched by a Gibson tirade in 1989. “If you had a microphone,” Gibson’s onetime fellow Dodgers employee said, “you were a jerk, and out to get him.”

Then Gibson walked in, slowly, and sat. He wore a comfy gray cardigan and took all questions, face displaying a Parkinson’s-induced blankness, voice higher and flattened, also related to Parkinson’s. He joked, detailed yet again the torn left hamstring and sprained right knee of 1988 and the events leading to A’s closer Dennis Eckersley’s infamous backdoor slider, praised teammates, appreciated fans. After 15 minutes came a pause for water, the room silent as Gibson brought the bottle to his mouth, shaking.

Later, before 53,595 fans, Gibson dutifully reenacted his ’88 triumph—the halting walk to the bat rack, the practice swings—but this time there was no Eckersley and it wasn’t nighttime; he looked pale in the afternoon sun. The crowd stood as one, saluting him with the same double fist pump that Gibson had unleashed rounding second to end Game One. After lofting a ceremonial first pitch, he answered with two last labored pumps, relieved that it was done.

The next day Gibson went back to Chavez Ravine, -warier but still game; the weekend figured to raise $200,000 for Parkinson’s. (The Kirk Gibson Foundation is dedicated to fighting the disease.) So he held court in a luxury box and told the stories, weathered the smiling faces and found himself reduced further. That night, the first 40,000 fans received a 30th-anniversary- Gibson bobblehead, seven inches tall with fist held high—the most tangible signifier yet of his new, softer image. You might even call it cute.

The winning home run? All that lovepouring from the stands? That’s the kid’s dream of sports. No one envisions the drudgery—17 years of games, 10,000 dirty hours of practice, the aching legs, long bus rides and late flights—that go into forging a revered place in baseball history. Or that all the hard work would lead, on a dull March Saturday, to a half-empty mall in California’s San Gabriel Valley.

But here is Gibson now, on glory’s flip side. No grass, no scoreboard: just the windowless confines of what was once a Kay Jewelers, and a charge to sign all manner of baseball paraphernalia until his hand gives out. He sits at a table with his 31-year-old son, Kirk Robert, hovering, surrounded by reminders of his younger self: armies of Kirk Gibson bobbleheads (standard and special edition gold), piles of pictures and cards and gloves and batting helmets and jerseys, stacks of programs and balls and bats. Even some bottles of Cabernet.

Earlier, a crowd of 450 had surged into a nearby storefront to pay for a glimpse, a handshake, a signature. Former Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda and ace Orel Hershiser were also there, but, says memorabilia dealer Jim Honabach, Gibson was the main draw. “The home run,” he says. “Biggest sports moment in L.A. history.” And in such brevity lies the key to Gibson’s unique place in the baseball firmament. He never once finished a full season above .300, never mind with 30 home runs or 100 RBIs or 40 stolen bases; the lone time he won a league MVP award, in ’88, he batted .290 with 25 homers.

No, Gibson’s appeal always centered on clutch at bats, fearsome competitiveness, maximum testosterone. In 1983, the same day he hit a ball 540 feet out of Tiger Stadium and into a lumberyard, Gibson lashed a drive to deep centerfield, all but caught teammate Lou Whitaker racing home and then sent Whitaker, the catcher, the umpire and the five spare baseballs in the ump’s pocket sprawling. Whitaker was tagged out, Gibson scored. In ’85 he took a fastball to the jaw that would require a hospital run and 17 stitches; Gibson angrily, bloodily, waved off the trainer and took first base, demanded to play the next day and clubbed a homer in his first at bat.

“A man’s man,” says former Tigers teammate Alan Trammell. “I’ve never met anybody like him.”

Indeed, Gibson’s fierceness created its own category—“That’s just Gibby”—with leeway and expectations unfamiliar to most. Maybe other pro athletes have flown themselves to home games, but who else has been excused from spring training to break (at 25,200 feet) a Cessna altitude record? Who else but Gibson—then 55—would turn a late-night trade talk at the 2012 winter meetings into a WWE tussle by head-butting and pinning Rangers general manager Jon Daniels to the ground? Who but Gibby—just to show Parky that he won’t go gently—would grind himself to exhaustion on a five-day, 800-mile snowmobiling trek in January across northern Michigan?

“I was lying on the floor bawling, and just kept repeating, ‘He’s always been Superman,’ ” says Tigers minor leaguer leftfielder Cameron Gibson, 24, Kirk’s youngest son, of the day he learned of his father’s illness. “He’s not supposed to be hurt. It’s impossible.”

Putting a price on such mystique isn’t easy; that doesn’t mean you can’t try. This morning’s base rate was $99 per signed item, $49 more for personalization. After scratching away for hours, Gibson suddenly raises his head and calls out, “Look.” I walk over. “This is one of my favorite photos,” he says. “From your magazine.”

The shot is from the July 17, 1995, issue, during his last season: A 38-year-old Gibson, back with the Tigers, in a collision at home plate, bulldozing Royals catcher Pat Borders. Two days before, Borders had not blocked the plate on a similar play and, Gibson says, before his next at bat admitted to Gibson that he’d lost sleep over it. “Because,” Kirk Robert chimes in, “he had wimped out.”

Reliving all this, his dad’s eyes gleam with that old mean delight. You can feel it as Gibson describes the next time he charged home: how both men knew what was coming, how Borders planted and Gibson unleashed his favorite football trick, learned at MSU, the Flipper, driving his right forearm into the catcher’s neck. Borders crumpled. (Borders, now managing at Class A Williamsport, didn’t respond to requests for comment.) “How’re you going to hold on to the ball when a truck runs over you?” Gibson crows. He points to the photo’s key reveal—the clinical way he’s going for Borders’s throat.

“Eyes on the target,” Gibson says.

Just as Dad taught him. Kirk grew up the son of public school teachers, Bob and Barb, in Waterford, an hour northwest of Detroit, with two protective older sisters. It’s puzzling, at first, when an athlete from bland circumstance competes as if sprung from hell; his parents saw Kirk’s restless intensity early and thought it innate. Still, tinder needs a spark. And before the teaching career and an earlier stint auditing taxes for the state, before serving on the USS Missouri in World War II, Bob was strong, fast, poor—and sure that the Depression had stolen his chance to play organized sports. He channeled his remaining ambition into his only son.

“He was real hard on me, very structured,” Kirk says. “Lunchtime in elementary school he made me run home, maybe a mile, had lunch ready, and we’d eat fast so we could practice before I ran back. If it was football, we’d be out in the backyard and he’d teach me how to carry it. Catch the ball! Catch it with your fingertips! Basketball, I’d be out shoveling the snow so we could go out and shoot.”

“He used to hate that, because Kirk wanted to play,” Barb says. “But, no, it was, ‘You get out there, and do that.’ ”

Kirk’s lone rebellion was the stray fastball he’d fire at his dad’s shins in junior high, but Bob liked that. Raw aggression and speed would carry his son until his athletic skills jelled as a Waterford Kettering High senior, enough to earn a football scholarship from the only big school that came calling. And Kirk hit the ground sprinting at Michigan State in 1975, alienating seniors by turning practice jogs into races of humiliation, shuddering the Spartans’ toughest defender with a crackback block, earning the starting flanker spot as a freshman.

Fourth game that year, the Spartans went to South Bend and beat Notre Dame 10–3; Gibson contributed only a message. Lined up opposite All-America cornerback Luther Bradley, he broke and never stopped. “Bradley starts backing up,” says teammate Mark Tapling. “Gibby speeds up and Bradley’s still backing up, and it was like, ‘Holy smokes, he’s not stopping!’ Ran right over the top of him, making his point: Here’s how it’s going to be today.”

Even then it was clear: He reveled in his mastery, especially one-on-one. That’s why football was Gibson’s true calling; unlike most people—and certainly most baseball players—he took elemental pleasure in physical menace, in breaking a man’s will by making him hurt. The fact that such ferocity came in an imposing package with soft hands and—as clocked by the Patriots in his senior year—4.2 speed made Gibson an outlier. “So big and strong, so fast, and his strides were so long that he tore up the ground: CARRRGGGH! CARRRGGGH!,” says Trammell, hands clawing air. “Literally, you could hear him running.”

“Gibby would sweep into a room, O.K.?” Tapling says. “He was big, had a big stride, long and purposeful. He never sauntered. And that creates a force field.”

His aura grew during junior year, when Gibson took up baseball for the first time since high school. The initial plan was to skip spring football and maybe gain leverage in negotiations with NFL teams. Then he batted .390 with 16 homers and 21 stolen bases. The Tigers drafted him with the 12th pick of the 1978 June draft (the NFL Cardinals drafted him in the seventh round a year later), and he spent that summer with Class A Lakeland, keelhauled daily by manager Jim Leyland. “I don’t give a f--- if you’re an All-American football player!” Leyland boomed in the car from the airport. “You want to drink all night and chase women? Go ahead. But you’ll be on that field with me every day at 8:30 a.m. until I send you to the big leagues. Understand?”

Gibson’s response? “I said, ‘Bring it on, bitch,’ ” he recalls. “My mentality was really crazy at that time.”

Crazy had its upside. Leyland tutored him mercilessly for six hours every day—outfield, baserunning and throwing drills, cuts in the batting cage—and then, at 2:30 p.m., began the team’s prep for that night’s game. Gibson only thrived. During one steamy BP in their second summer, Leyland finally barked, “That’s enough,” but Gibson shook him off. “I had this big incinerator full of baseballs and fed him every one,” Leyland says. “He’s the only guy that could hit the whole incinerator—and still take more.”

The downside? Gibson got kicked out of his last college football game for fighting the entire Iowa Hawkeyes bench in East Lansing, and he had no clue how to reset his motor for baseball’s daily grind. Three days after he was called up to Detroit in the fall of 1979, Gibson demanded to pinch-hit against Yankees flamethrower Goose Gossage (“I want him!”) and struck out flailing on three pitches. When pitcher Jack Billingham began hazing him the next spring, Gibson sent him flying through the training room doors, leaped on his chest and vowed to kill him. “Go ahead!” Gibson screamed. “Say one more word!”

Manager Sparky Anderson didn’t help matters by dubbing Gibson the next Mickey Mantle; for every booming homer and stolen base, there was a weak throw from rightfield, a fly ball bouncing off his head or some new injury. At best a Gibson at bat resembled a man hacking through a jungle: He hit under .200 in May, July and August in 1983, looked lost on the field and off, batted .227 for the season and was booed regularly. He boasted of slapping an abusive fan in a Detroit bar. Anderson busted Gibson down to part-time, skittering just out of reach when Gibson lunged at him. But Sparky couldn’t run forever.

One afternoon in Seattle, with Gibson sprinting in the outfield, the 49-year-old Anderson lined up like a cornerback and challenged him to run a route. The manager apparently hadn’t seen what happened to Luther Bradley. “Ran his ass over,” Trammell says.

“It hurt him: He was an old man,” Gibson says. “He got up and had tears in his eyes, hat was off, hair was all f----- up. He’s like, ‘You sonuvabitch! You’re crazy!’ I said, ‘Get your f------ ass out of here because I’ll do it again.’ I just couldn’t contain it.”

Gibson isn’t speaking only about competition. He approached too many interactions—especially once the failures began to mount—with a nasty edge. His parents’ breakup in the early 1980s couldn’t have helped matters, but Gibson remained close to both; he’s certain that his problem rose from within. “I enjoyed dominating people,” he says. “When I played football? You dominated, you hurt people and you didn’t care. I couldn’t separate that off the field.”

By 1984, Gibson had begun trying to do just that—but the process would take years. I knew nothing about it then. All I could see from afar, with SportsCenter in its infancy and the Internet a dream, was that the Tigers had catapulted to one of the greatest starts ever and that Gibson, en route to 91 RBIs, 27 homers and 29 stolen bases, was realizing his promise. Me, too: I began the season waiting tables—fresh out of college, baseball besotted—and it seemed wondrous when, come summer, I landed a newspaper gig covering weekend games in the Bay Area. Getting to glimpse the first-place Tigers in early September felt like a gift.

It was a Sunday, late afternoon. Detroit had won 6–3, and after interviewing the A’s, I wanted a close-up look at everybody’s pick to win the Series. I pushed open the door to the visitors’ clubhouse. A young woman, interning with TheDetroit News and soon to return to college, hurtled by, in tears. I looked up, and here came Gibson on the chase: bare-chested with a hand on his crotch, gleefully shouting the woman’s name and the words, “You want to f--- me.”

In the years since, covering athletes at all levels, I’ve never seen an act more vile.

What happened next? A more obviousquestion today. If what Kirk Gibson did that Sunday in Oakland happened in this age of cellphone cameras, social media and #MeToo, his season—if not career—would be over by the time the team landed the next day in Detroit.

But then? Nothing happened next. Like every other reporter present, I wrote nothing about it. The young woman herself never reported it, and she has turned down every request to discuss it publicly (and requested that SI not use her name now). I heard that she received private apologies from a couple of players, the private support of scribes near and far. The incident became a staple of Detroit media lore, and her own paper reported it—with one witness describing it as “the most vulgar personal attack imaginable”—but only six years later, and buried deep in a piece on the increasingly volatile relations between the press and pro athletes.

Not that Gibson’s bullying wasn’t considered, at the time, odious. It just seemed typical then, especially in baseball. Yes, some courteous players occupied every clubhouse. But I didn’t even cover the beat full-time, and within three years of witnessing Gibson’s abusive behavior, Reds pitcher John Denny went after my best friend, the Cincinnati Post’s Bruce Schoenfeld (Denny was assigned to six months in a rehab program, and charges were erased); A’s slugger Dave Kingman sent my Sacramento Bee colleague, Susan Fornoff, a live rat in the Oakland press box; and Jim Rice of the Red Sox tore up the shirt of another close friend of mine, Steve Fainaru of TheBoston Globe, in a clubhouse scuffle.

Some of this was due to personal grudge or the impulse to protect imagined turf. Some was by design. “We’d lose six or eight in a row, and Sparky would say to me, ‘The boys are a little tight, why don’t you take a little pressure off ’em? Pick out a media member,’ ” Gibson says today. “[Detroit beat writer] Brian Bragg came in one day between games of a doubleheader, and he’d written something about Lance Parrish—and it wasn’t bad. But I made the biggest scene: ‘Don’t you come by my f------ locker!’ I was way out of line. You know what, though? The team started winning ball games.”

One reason the intern didn’t report her clash with Gibson is because, she told TheDetroit News in 1990, the abuse heaped on women reporters seemed no worse—just different—than what her male colleagues endured. Perhaps. But in the ’80s women in clubhouses were grossly outnumbered and subjected to sexually tinged verbiage. Jockstraps were tossed. Players thrust their hips back and forth. Any chance to embarrass female journalists was seized upon.

“Every time I went into a clubhouse, my stomach was in knots because I didn’t know what I would face,” says Lisa Nehus Saxon, who covered the Angels and the Dodgers from 1979 to 2000 for various papers and now teaches media at Santa Monica College.

But one team was particularly brutal. “The Detroit Tigers, without a doubt,” pioneering Toronto scribe Alison Gordon told a Michigan newspaper, in 1982, when asked to name baseball’s worst clubhouse. “They’re babies ... the last time I went into their locker room for a post-game interview, one of the players shouted out, ‘Look out! Here comes the old whore!’ ”

Indeed, even with stand-up presences like Trammell, Parrish, Dan Petry and hitting coach Gates Brown, the Tigers seemed particularly vexed by the incursion of women reporters into the clubhouse. The staff ace, Jack Morris, later gained infamy for telling the Detroit Free Press’s Jennifer Frey, “I don’t talk to people, especially women, unless they’re on top of me or I’m on top of them.”

And the front office didn’t seem to care. General manager Bill Lajoie, who died in 2010, was given to playing down Gibson’s off-field behavior so long as the outfielder remained a galvanizing force. Three weeks after the display in Oakland, Gibson mooned one woman during a pennant-clinching celebration in the clubhouse and, as Free Press columnist Mike Downey wrote then, joined pitcher Dave Rozema, Gibson’s future brother-in-law, “to make a sandwich out of another one.”

“Rude, crude and misogynistic,” Downey says of Gibson in those days. “He would say and do things, particularly about and toward women, that were unimaginably awful. One time [first baseman] Darrell Evans turned to me—quietly, because he didn’t want to cause trouble—and said, ‘Class act, Kirk.’ Several teammates found his behavior appalling but didn’t want to disrupt team harmony by calling him out. Because that was a magical season in Detroit.”

It was, but I had lost interest.Which is to say, I was young and brimming with self-righteousness, figured Gibson a cancer and baseball an accelerant, and found myself backing away from the sport just as his apotheosis arrived. After batting .417 against the Royals in the 1984 AL Championship Series, he single-handedly dismantled the Padres in Game 5 of the World Series: crunching a first-inning homer into the upper deck of Tiger Stadium; impulsively tagging up on an infield pop-up to score in the fifth; exacting storybook revenge upon his first and best tormentor, Goose Gossage.

That came in the eighth inning, Tigers leading by one. With first base open, Gossage refused the intentional walk; in his career he had faced Gibson 11 times and fanned him in seven of them. Standing at the plate, Gibson turned and bet Anderson $10 that his time had come. The three-run homer he lashed was framed nationwide as pure baseball payback; few were aware that it was also the most dramatic reinforcement of a new mindset.

Ten months earlier, embarrassed by his anemic performance in 1983 and poised to quit, disgusted by his negativity and scared by deteriorating relations with family, team and the public, Gibson phoned his agent, Doug Baldwin. “I can’t handle this any more,” he recalled in his autobiography, Bottom of the Ninth. “I’ve got to get some help.” Baldwin recommended Seattle’s Pacific Institute, a self-styled high-performance clinic for strivers in politics, business and sports. Gibson flew there and over four days worked on adjusting his attitude through “a common-sense approach to becoming a better human being,” says Frank Bartenetti, the staffer who took Gibson in hand. How? “Let me see if I can say this right: I’m a genius.”

In their talks, Bartenetti urged Gibson to wield his mind as a tool, envisioning success, drawing on previous victories to bolster confidence. Gibson spent the entire 1984 season layering all that onto his game and took his spectacular turnaround as the clearest result. He returned to the institute that -offseason—this time with his mother—and checked in often with Bartenetti by phone. Soon, subjects were expanding beyond the field.

For example, at 27, Gibson had to re-learn how to be nice. It was a homework assignment. Next time you’re in a grocery store, Bartenetti told him, ask the cashier how she is; tell her to have a great day today and an even better tomorrow. Gibson’s first attempt was nerve-racking.

“I’m standing there in the line, my grumpy-ass self, and thinking, God-dang, I got to do it,” he says. “It was that hard for me.”

But Gibson survived, and Bartenetti’s wider lessons began to take. “Things don’t just blow by me; I always analyze them,” Gibson says. “I started to appreciate. At some point you realize that it gets lonely. You’re going to be lonely if you keep going on that way, if you keep dominating people away.”

Gibson became a family man in 1985, marrying longtime girlfriend JoAnn Sklarski and helping raise her eight-year-old daughter, Colleen; the next year Kirk Robert was born. Former drinking buddies speak in awe, still, about Gibson’s transformation to devoted husband and dad, but the public heard something even more stunning. Alone among his contemporaries, unlike, say, Kingman and Denny and Rice, Gibson began dissecting his flaws. Always capable of being insightful and self-aware—with those willing to navigate his moods—Gibson repeatedly termed his younger self “a self-centered, egotistical jerk.” Over the ensuing years he conceded “personality defects” (or, as he says now, “a social disorder”), and when it came to Monaghan’s comment, he said, “Let’s be honest: I was a jerk. He was half right. I wasn’t a disgrace to the uniform, but I was crazy.”

His progress had limits. Even Bartenetti, who loves Gibson like a son, calls him a “bad listener”; he never fully shed his prickliness, and those who irked Gibson during his first stint as a Tigers TV analyst, from 1998 to 2002, may still be shellshocked by his thunderingly profane responses. “Gibby’s complicated, but I’m definitely in that camp defending him to the hilt,” says Mets play-by-play man Josh Lewin, who paired with Gibson in the booth. “He’s not the best. He’s not perfect. He’s a very kindhearted guy who’s tortured in ways that we’ll never understand. I don’t know what makes this guy tick. No one seems to know. But he’s fiercely loyal to the people he decides to give a s--- about.”

And many reporters of that era say that when Gibson arrived in L.A. in 1988, his harassment of women journalists had all but ceased. “He never said anything crude to me that he wouldn’t have said to a man,” says Nehus Saxon. “By the time he got out here, he was much tamer.”

“He clearly began to mellow,” says Downey, who joined the Los Angeles Times in 1985. “He wasn’t pulling that stuff anymore, as far as I know. He was cocky and couldn’t quite get rid of that, but his teammates loved his competitiveness. I believe he had definitely matured.”

As far as I knew, Gibson never spoke publicly about lewdly running that Detroit News writer out of the clubhouse; he never addressed the matter with her. But when I mentioned, in Lakeland, that I had seen him at his worst, in Oakland in 1984, he cut in: “Chick was there? A chick?” Then Gibson instantly recalled the intern’s name, called her “a great person.” Neither she nor he would say what led to the harassment, but Gibson said, “It was a weird time in the locker room, would you agree with that? We’re so far down the line from that. She probably doesn’t like me. I feel bad about that. Being reflective, it was wrong. That was wrong. I could’ve handled it better.”

He went on to say that having been raised by a loving mom and two strong sisters, he is “very respectful of women.” He calls himself a strong proponent of Title IX and points to his 22-year history of raising funds for Michigan State that benefit women’s sports. “I try to undo things,” Gibson says. “I’m certainly not a guy who says, ‘I’m never going to apologize.’ ” Some believe that his Parkinson’s has fostered, as Tapling says, “a kinder, gentler Gibby.” Gibson doesn’t think it’s that simple.

“I hope so, but when I was a jerk, I did a lot of good things, too,” he says. “I don’t care what anybody says: In my heart there’s always been a good person, but just as I did some good things in baseball, I did some bad things, too. As a person, I try to get better every day.

“Does it still happen? I try not to engage in a negative way, but it does. You’ve had negative engagements in the last week; you might be in your car, and one day feel like flipping a guy off and the next you might say, ‘Hey, man, sorry.’ It’s not just me. All the s--- we’ve been talking about? I’m just like everybody else. I’m not a freak, O.K.? To be fair, you can examine me all you want about my negative traits. We’ve all got that to deal with. I want to be the best person I can be. I hope that I can help people.”

Revisiting old public figures is ajournalism chestnut. SI has its Where Are They Now? issue, of course, and I’m one of countless writers who have caught up with some actor, politician or athlete from the past. The obvious theme is change—the fade from the spotlight, the loss of physical or mental skills, the move to a new career—and how the star is navigating it. But in truth we’re also taking stock of the personality we remember, seeing how it copes with the real world, all the while wondering (sometimes in hope, sometimes in fear) if anyone truly changes at all.

That question feels even more pointed in the case of Kirk Gibson. With athletic gifts and a headlong style geared for football, his baseball career became marked less by conventional achievement than by a series of private wars—Gibby vs. his body, Gibby vs. fame, Gibby vs. himself—and the victories won by his untamable will.

He’s the first to admit: The same impulsivity that led a gimpy Gibson to growl, “My ass!” after hearing Vin Scully announce that he wouldn’t be able to pinch-hit during Game 1 of the ’88 World Series also led him to assail an intern. No, as a player and a man, Gibson wasn’t like you or me. He didn’t plan; he was too much id, a puzzle even to himself, and if part of us insists on seeing that repaired—or, as Gibson puts it, “channeled in the proper fashion”—another hopes that the most winning part, at least, survives.

For now, anyway, that seems likely. I first allowed that Gibson might well have evolved after the four hours I spent with him in Florida; after interviewing former teammates, his mother, wife and sons, some 30 people who have loved, respected or loathed him over the years; after hearing how he had ratcheted back his presence, becoming a voice of positivity and reason, for 11 years as a coach in Detroit and Arizona; after seeing how he, in 2011, his first full-time season in charge, won the NL West title and Manager of the Year with the Diamondbacks.

Gibson’s intensity rekindled during his first years at the helm in Arizona, but it was measured; staff and media in Arizona reported no sign of bad Gibby. Yes, he ordered a pair of old-school, retaliatory beanings during a June 2013 game at Dodger Stadium, touching off two bench-clearing brawls that resulted in suspensions and fines on both sides. But it’s notable that during the on-field chaos—with usually placid Dodgers manager Don Mattingly hurling the usually placid Trammell to the ground, and usually placid Dodgers coach Mark McGwire shoving and grabbing a fistful of Gibson’s shirt—it was Gibson, of all people, who seemed the most composed.

By then, he was also the most fragile man on the field. Surgeries on his neck and left shoulder had left him stiff, sapped his energy and masked symptoms that turned out to be Parkinson’s. In 2014 the bottom fell out. The D-Backs’ roster, built in his hard-nosed image, mirrored Gibson’s physical decline and went 63–96; Tony La Russa was hired to clean house, and fired general manager Kevin Towers and also Gibson with three games to play. Current team president Derrick Hall says the club retains “enormously positive feelings” for Gibson, not least because he demanded that his team engage daily with fans.

“Some players said, ‘Gibby, you never would’ve,'” says Hall. “He said, ‘You’re exactly right—and I wish I had. The things I missed out on because I was so selfish and angry and upset, you need to do.’ And he practiced what he preached—did anything we asked, always signing autographs, taking fan pictures: tremendous. He’s one of my favorite guys of all time, and one of my favorite managers I’ve ever worked with.”

I softened a bit more on him in Los Angeles last March, during Gibson’s press conference to start the 30th-anniversary tribute. Up popped a softball question about his emotions during that limp around the bases, a chance to brag about his grit. Instead Gibson spoke again of how he had long been “a jerk headed in the wrong direction” and how, just before famously pumping his fist, he said, “I immediately thought about my parents because [my behavior] had hurt them.”

Bob, who died in 1999, and Barb, 88, who still lives in Waterford, were there that night, behind home plate.

“I had hurt them,” Gibson went on. “And I had told them, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll get it straight, we’ll have our day.’ So my first thought when I put my arm out, obviously was ‘We won the game,’ and secondly my parents. I was just past first base. There’s a saying: It all evens out—which, we know, it doesn’t. But you know what? For a second, I believed that again.”

Then, his third day in L.A. for the anniversary, something else happened. It was near the end of the autograph signing at the mall in the San Gabriel Valley. Earlier, when some ailing faces had come through the line, Gibson told one woman in a wheelchair, “You can’t give up, you know!” and I dismissed it as little more than a nicety. But I was chatting with Kirk Robert when a man in his late 40s approached and said, “I’m sorry: You’re Kirk’s son?”

And he began talking about his mother’s dozen years with Parkinson’s—the first ones manageable, the last few brutal—and I recalled Gibson’s telling me that his symptoms had been misdiagnosed for years, that he had slurred and limped so often during his last years in Arizona, as far back as 2012, that a friend worried that he was having mini-strokes. I recalled Gibson saying how Parkinson’s robbed his sleep, made it tough to defecate or punch in a phone number; how he’d been out on Figueroa Street the night before and had to fight to stay balanced while walking on a curb.

And now the man, Art Yoon, was saying that Gibson, earlier, had wanted him to wait so that he could try again to call Yoon’s mom, Choon, but fans were still surging in and now Yoon had to leave for work. “Tell him thanks,” Yoon said, and he walked away. Two minutes later, I chased him down outside, and told him I was a reporter.

Choon, 77, had also been at Dodger Stadium, with her husband, three decades before, when Gibson homered off Eckersley. She had planned to come today, on a mother-son outing to meet her hero at last, but her Parkinson’s flared and she could barely stand. When Gibson heard that, he said, “Let’s get her on the phone now,” and pulled Art into a back room to try. The call kicked to voice mail.

Art began edging away then, but Gibson urged him to “hang tight.” A bit later, while sitting and signing, Gibson searched the room for Art, caught his eye, and pantomimed tapping out a phone number. Art nodded and tried again: voice mail. He shrugged; Gibson nodded. And at a point in their brief exchange Art welled up, nearly lost it entirely from a combination of frustration, sadness, the lost chance to give his mom a surprise lift—and something that took months for him to put into words.

The moment passed. When I caught up with Art again in June, he said that he’d left his mom’s number with Kirk Robert, but can’t say if Gibson ever got through. Choon can barely cross the room now; there are days when her English is unintelligible; she doesn’t know how to retrieve voice mails. But in Gibson’s small efforts—the kind of dismissable niceness that once seemed beyond him—her son witnessed an act as indelible for him as some 34-year-old ugliness remains for me.

“He’s a legend here in Los Angeles,” Art says. “He probably can’t walk 10 feet without someone wanting to buy him a drink. Despite that? He heard my mom’s story and tried— twice—to talk to a woman who is seriously deteriorated. Though that was a very meaningful moment for her in 1988, I don’t know if she’d even know who he is right now, and he took the time anyway. That level of humanity is uncommon, and Kirk isn’t the only Dodger, the only celebrity, I’ve met. That is rare.”

Later that evening, Art made it to Choon’s house in Irvine for dinner. As they were setting the table, he told her the whole story, beginning with a coy, “Hey, you get a call from Kirk Gibson today?”

“The baseball player?” she asked.

A bit more than that, it seems. After all.