Nine Innings: Appreciating Jose Ramírez's Remarkable Season and Cole Hamels's Turnaround

SHINING A LIGHT ON JOSE RAMíREZ'S TERRIFIC SEASON

By Tom Verducci

Before the engraving starts on the American League MVP plaque for Mookie Betts, take a minute to appreciate the astonishing season of Cleveland third baseman Jose Ramírez. This is the same guy who hit eight home runs through his first 180 big league games, who was so lightly regarded that just two years ago the Indians signed a washed-up, 36-year-old Juan Uribe on the eve of spring training camp to play third base rather than Ramírez (truth is, Giovanni Urshela was ahead of Ramírez on the depth chart), and who is built like Uribe, his mentor, who had such a bad body he was known as “El Pavo”—The Turkey.

This season Ramírez has hit 37 home runs. With three more stolen bases, he will join Joe Carter (1987) and Grady Sizemore (2008) as the only Cleveland players with 30 homers and 30 steals in the same season. Bigger still, because of the freakish strength of his hands, Ramírez is tracking to become only the fifth 30-30 player ever with an OPS greater than 1.000 while striking out fewer than 80 times.

This kind of skill set—power, speed and contact at those elite levels—has been seen only in seasons from Vladimir Guerrero (2002), Barry Bonds (1992, 1996), Willie Mays (1957) and Ken Williams (1922).

Still think Betts has the MVP locked up?

Betts (27 homers, 26 steals, 1.049 OPS and on pace for 88 strikeouts) will be close to that group. Against Ramírez he wins most every head-to-head competition on rate stats. But Ramírez, 25, has the distinct edge on volume over Betts, who missed 15 games in May and June. Ramírez has more home runs, RBI, walks, total bases, stolen bases, extra base hits and times on base.

“What he does in the batter’s box is the closest thing I’ve seen to David Ortiz,” said Victor Rodriguez, assistant hitting coach for the Indians, who formerly worked for the Red Sox. “I mean, he studies pitchers like nobody else. He has a sense not just of what pitchers will try to do, but what they will try to do with him. It’s like a gift. He seems to know what’s coming, and when he gets it he does not miss.”

“His hands,” Cleveland manager Terry Francona said, “are incredibly strong. By now around here we know that when he comes back to the dugout after he hits a home run [and celebrates], you better be careful and at least brace yourself, because you could get hurt by those hands.”

Ramírez's career arc is astonishing. He never made a Top 100 prospect list. In 2014 Baseball America ranked him ninth in its organizational top 10, behind guys like Tyler Naquin, Cody Anderson, Dorssys Paulino, Ronny Rodriguez and C.C. Lee. He hit just seven homers in 1,067 plate appearances in the minors before being called up to the big leagues in September of 2013, just prior to his 21st birthday. He looked like a nice enough super-utility player.

While Uribe fizzled in 2016, Ramírez broke out (.312/.363/.462), which prompted Cleveland to smartly sign him to what now is a crazy cheap extension: seven years of control (if two team options are exercised) at $52 million max.

What is the X-Factor for Every Playoff Contender?

Since then Ramírez just keeps getting better. His rise in slugging percentage since 2015 is a player development department’s dream: .340, .462, .583, .606. Here are his yearly home run totals in the pros: 1, 3, 3, 7, 7, 11, 29, 37. He’s added about 30 pounds to what was a 165-pound body. You probably have to go back to Howard Johnson (1987) and Sammy Sosa (1993) to find 30-30 players who climbed to such heights so unexpectedly.

What makes Ramírez such a punishing hitter is what he does with fastballs. A stunning majority of his value as a hitter is wrapped in his uncanny knack to hunt fastballs and just hammer them. These numbers (entering this weekend) are testament to the strength and speed of his hands:

• Ramírez is hitting.326 and slugging .738 off fastballs, but only .209 and .372, respectively, off breaking balls.

So why throw the man any fastballs? Truth is, pitchers try to be judicious with their fastballs against him. Matt Carpenter, for instance, has seen 133 more fastballs than Ramírez, and only Bryce Harper and Giancarlo Stanton see a fewer percentage of fastballs in the zone. It’s just that Ramírez pounces on the few hittable ones he sees.

• Ramírez has hit 31 home runs off fastballs, the most in the majors. (Khris Davis is next with 27.) Of those 31 homers off heaters, Ramírez has smashed 27 of them to the pull field.

“He stands right on the plate because he knows pitchers can’t beat him in,” Rodriguez said. “So that makes the outside [fastball] down the middle to him. And when he knows what to look for, and because his hands are so strong, he’s going to pull that pitch even if it’s away.”

• Ramírez has swung and missed at only 15 fastballs all year—out of 388 swings.

• Ramírez has struck out swinging only four times all year on fastballs in the strike zone. (The pitchers: Fernando Rodney, Nick Blackburn, Michael Fulmer and Kyle Gibson.)

Anthony Bosch Reveals Why Ryan Braun Got Caught for Using PEDs

• Ramírez is on pace for a bWAR of 9.9, which threatens the 10.1 of Al Rosen (1953) as the best ever for a third baseman.

• He would be the fourth 30-30 third baseman in history (Tommy Harper, Johnson twice and David Wright), but he would own the highest OPS and the fewest strikeouts among them.

The Indians have had a laughably easy road to the postseason. They are 56-32 against losing teams and 18-24 against winning teams. They have won nine games all year against winning teams on the road. They will be first team since the 2010 Reds to win a division with a losing record and fewer than 25 wins against winning teams.

In short, they haven’t been challenged, which means there have been few big moments for Ramírez to showcase his MVP value. Big hits in September will not exist.

But we should begin to measure Ramírez against not just Betts but also the greatest power-speed-contact seasons in history. He is on track to hit more than 40 homers and steal more than 30 bases without striking out 80 times. Only one player in history ever had a season like that: Barry Bonds of the 1996 Giants. San Francisco finished last in the NL West that year, and Bonds finished fifth in MVP voting.

HOW HAS COLE HAMELS TURNED AROUND HIS SEASON WITH THE CUBS?

By Jon Tayler

Among the rush of trades that went down in July, the one that sent Cole Hamels from the Rangers to the Cubs was easily overlooked. That made sense: The 34-year-old lefty looked close to finished with Texas, posting a 4.72 ERA and allowing 23 homers in 114 1/3 innings. Chicago gave up next to nothing for him and his addition seemed more designed to plug a rotation hole than an attempt to acquire the front-line pitcher he no longer resembled.

Fast forward a month, though, and Hamels has been arguably the most meaningful player moved at the deadline. In five starts for the Cubs, he’s allowed just four runs—three earned—in 34 innings for a sparkling 0.79 ERA. That includes not a single homer given up. On Thursday against the Reds, he even went the distance, giving up only a run in nine innings for his first complete game since Aug. 5, 2017. Most importantly, he’s taken the ace mantle for a Cubs rotation that’s been awful since the All-Star break. But how has the former All-Star turned it around on the North Side?

It starts, perhaps fittingly, with the fastball. Hamels’ four-seamer has never been a heater, never averaging more than 93 mph in his 12-year career. Consequently, he’s been a diverse pitcher, working in cutters, sinkers, changeups and curveballs to complement the fastball. But this season, his four-seamer fell apart: Despite throwing it just 40% of the time—a career low—it was tagged for a .378 batting average and .805 slugging percentage before his trade.

Things have changed dramatically with the Cubs, though. Despite that pitch’s ineffectiveness, Chicago has Hamels throwing it more often—up to 52.6% of the time. But the results aren’t what you’d expect: a .286 batting average and slugging percentage, as well as dips in average exit velocity (by nearly 10 mph) and launch angle (by four or five degrees). Hitters are no longer barreling Hamels’ fastball, which in turn has led to a spike in ground-ball rate, a drop in homers, and more effectiveness on his breaking and offspeed pitches, as both his changeup and slider have seen big jumps in swing-and-miss rate in the month of August.

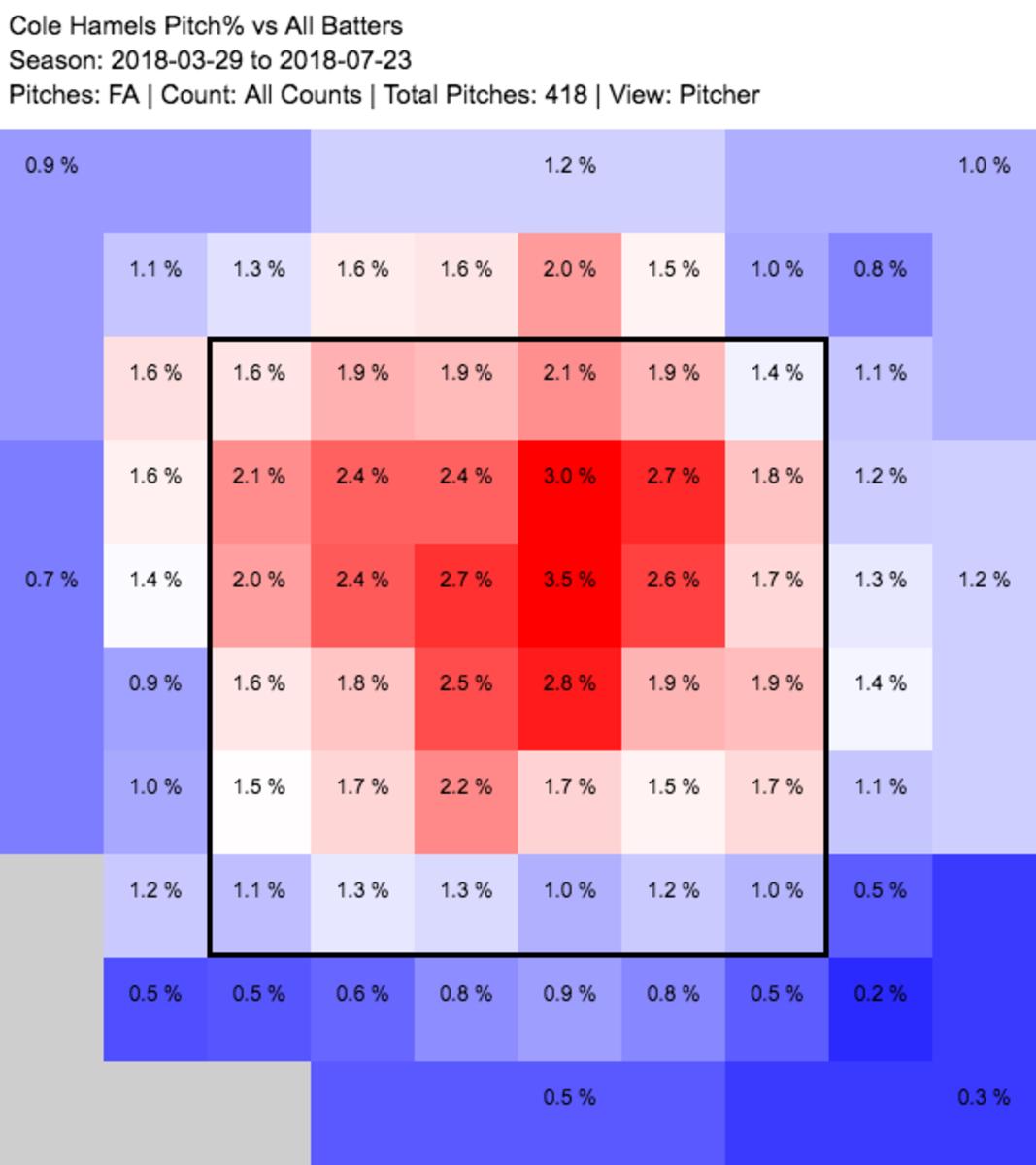

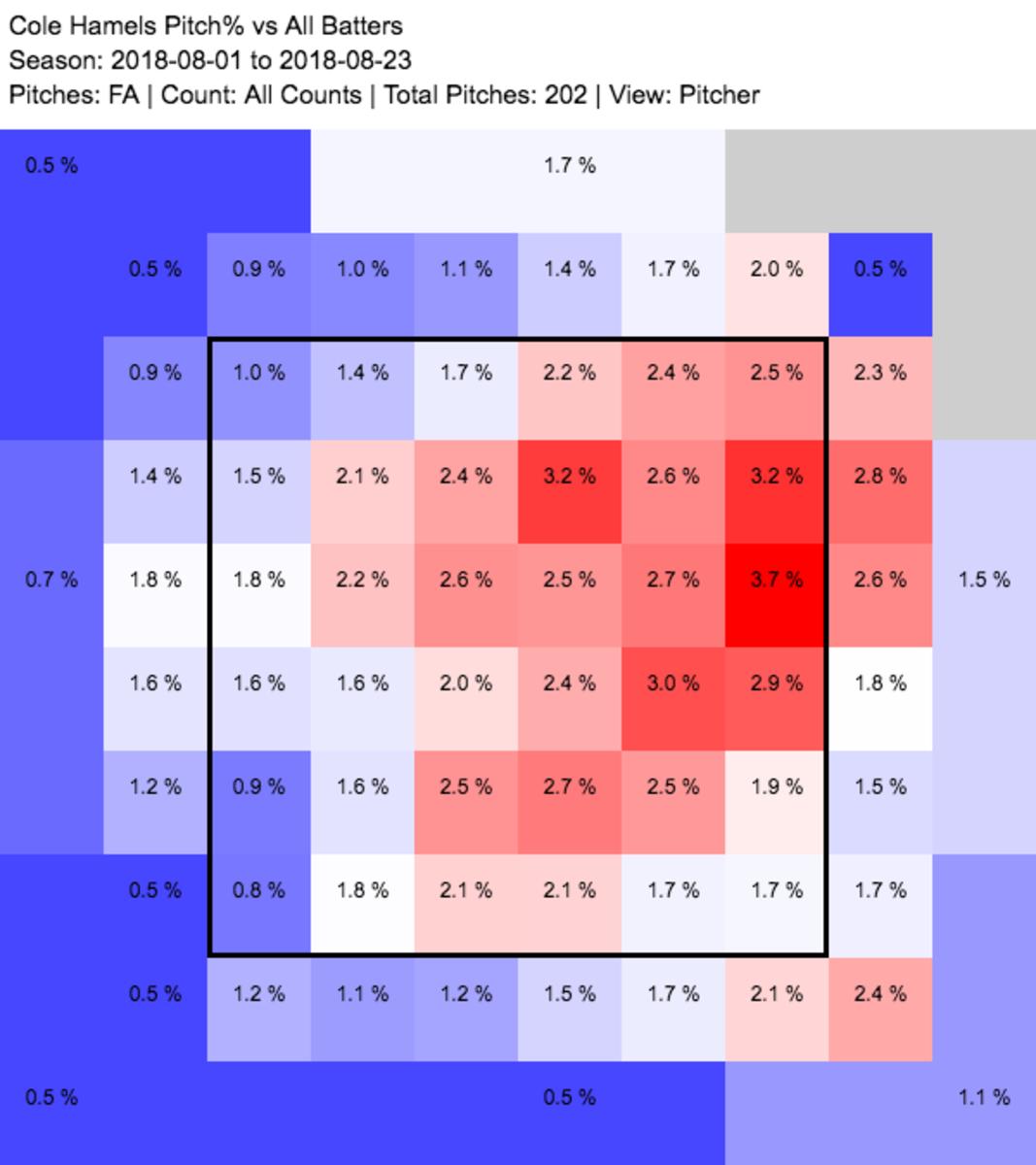

The key is likely location. Check out these heat maps of Hamels’ four-seam fastball usage; the first is with Texas, the second with Chicago.

Notice that, with the Rangers, Hamels was more or less putting his fastball right down the heart of the plate—a gamble for anyone, and downright foolish for someone who can barely crack 93. With the Cubs, though, he’s started burying the fastball in on righthanders and keeping it away from lefties.

There are other factors at play, too. Always a groundball-heavy pitcher, Hamels is probably benefiting from an upgrade in defense: The Cubs have the fifth-highest defensive efficiency in baseball (.703), while the Rangers rank 24th (.681). He’s also working more in the strike zone, helping to cut down on his walk rate.

What’s unclear is how long Hamels can keep this up. A home-run rate of, uh, zero is patently unsustainable, and teams will adjust to his newly fastball-heavy approach. But if nothing else, Hamels has at least kept the Cubs afloat at a time when they badly need it, with Jon Lester struggling, Jose Quintana and Kyle Hendricks uneven, and the back of the rotation a constant mess. Up four games on the red-hot Cardinals in the NL Central, Chicago is in good position to claim a third straight division crown. For that, the team can thank a trade that looked minor at the time but has proven to be anything but.

EXAMINING JACOB DEGROM'S SEASON IN AN ALTERNATE UNIVERSE (WHERE THE METS ARE AVERAGE)

By Michael Beller

You already know plenty about the season Jacob deGrom is having. He leads the majors with a 1.71 ERA. His WHIP is below 1.00. He has 214 strikeouts in 174 innings. He may win his first career Cy Young. If he does it, he will have earned it pitching for a terrible team that may keep him from having a win-loss record better than .500, which would be a first in MLB history.

Forget about the season deGrom is having with the Mets. Let’s think about the year he could be having with a different team. Specifically, if deGrom were on a team perfectly average in every respect—getting the average run support for a team that scores an average number of runs per game and has an average bullpen—what would his record be?

First, let’s nail down deGrom’s average start. Keeping things as simple as possible by simply dividing innings pitched and runs by starts, deGrom goes seven innings and allowed 1.27 runs in an average outing. The league-wide average for runs per game is 4.45, which is 0.36 more runs per game than the Mets score. They score about half a run less for deGrom than their average, though. His support of 3.65 runs per game ranks 113th out of 126 qualified pitchers. Among those 126 pitchers, the average support per game is 4.48 runs. DeGrom, meanwhile, has received five or more runs in nine starts, and three or fewer in 17.

Giants' Buster Posey to Undergo Season Ending Hip Surgery

The Mets’ bullpen ERA of 4.62 ranks 25th in the majors. Their relievers are slightly better than league average in save percentage, but have given away four games in which deGrom left with the lead. The bullpen hasn’t been quite as big a problem as the offense, but it hasn’t been spot-free, either.

OK, let’s assume deGrom’s perfectly average team was perfectly average every time he pitched. The first thing we can do is automatically give him a loss every time he allowed more than four runs this season. That has happened in…zero of his outings. In fact, deGrom has allowed more than three runs once all season, and has surrendered more than two five times, two of which were in April. He has pitched at least six innings in 23 of 26 starts, and in every one since the middle of May.

According to Team Rankings, the average team scores 3.02 runs per game in the first six innings. The Mets, however, rank 25th with 2.63 runs per game. If the Mets gave him that perfect average, he would have left the game with the lead in 18 of his starts this season. If we’re assuming he gets the average run support of 4.48 runs per game, then he would have left a few more with the lead, or the Mets would have tacked on a run or two after he departed. Teams surrender an average of 0.84 runs per game in the last two innings, and 0.35 runs per game in the ninth. With the averages we figured for deGrom earlier, we can assume that, on an average team, opponents would score 2.1 runs against his team in a typical start.

Add it all up, and you get a gaudy record. It’s safe to say that deGrom would have at least 15 wins, and possibly 17 or 18, if he were on an average team. Alas, he’s on the Mets, which makes him 8-8. If nothing else, the Mets might help deGrom make history this season.

ROUNDTABLE: WHAT'S ONE NUMBER THIS SEASON THAT BOGGLES YOUR MIND?

Emma Baccellieri: 8.23: There are only eight players in baseball history who’ve walked more than eight batters-per-nine in 100 innings pitched, and Tyler Chatwood is now one of them with an 8.23 BB/9. (Right now, he ranks fifth.) It’s unclear how much more he’ll get to pitch this year, given his recent hip injury, but he’s currently on a rehab assignment and with another start or two, he has a chance of going for perfection here: 9 BB/9, or at least a number that will round up to it. There’s only one pitcher in baseball history who’s achieved that terrible ratio, but that example might actually provide some hope for Chatwood. At 1951, 31-year-old Tommy Byrne completely lost his command, walking more than one-fifth of the batters he faced. A few years later, though, everything snapped back into place for him. In 1955, he even received some shine in end-of-season award voting, with a 3.15 ERA and 16-5 record. Chatwood’s walk rate is a historically ridiculous number as is, but even if it somehow gets worse, he can take solace in the idea that a rebound is possible.

Gabriel Baumgaertner: 7: I’ll go with a very recent and very basic number. Kendrys Morales set the Blue Jays record by homering in seven consecutive games (and counting). He became the first player since Kevin Mench in 2006 to do so and is one game shy of tying the MLB record. It’s the purity of the accomplishment that astonishes me. Hitting a home run on at the Major League level has been a dream of countless boys, teenagers and men for generations. For Morales, a Cuban defector, it was the dream of so many of his countrymen never able to make it over to the states.

Sometimes, it’s fun to embrace the cosmic forces and whims of the baseball gods. Morales’s streak is one of those moments.

Michael Beller: .268: Do you realize how crazy it is for Jose Ramírez to have the epic season he's having while posting a .268 batting average on the balls he puts in play? Matt Carpenter, Alex Bregman and Francisco Lindor are the only other players in the top 20 in wOBA with BABIPs south of .300, but they’re all at .286 or better while sitting at least 33 points behind Ramirez on the wOBA leaderboard. It’s entirely possible that a guy hitting .290/.403/.606 with 37 homers and 32 doubles could be getting a little unlucky on balls in play, and that’s not something you see every season.

Connor Grossman: Three: I have an inexplicable fixation on instant replay, and per the stat keepers at MLBReplayStats.com, the Brewers have had three challenged calls overturned all year. Three. That's incredibly putrid. They've challenged 25 calls as of this writing, producing a .120 "winning percentage" (or "challenge effectiveness," as the site calls it) on replay challenges. According to archived replay stats, no team has ever had fewer than 11 overturned calls in a season. Additionally, no team has posted a worse challenge effectiveness than .250 (last year's Blue Jays). The Brewers' replay operation is an anomaly. Maybe they don't have MLB.tv.

Jon Tayler: 100-plus: As of Sunday’s results, three teams—the Orioles, Royals and Padres—are on pace to lose 100 or more games this year. That would make 2018 the first season since 2002 to have three or more teams reach the century mark in losses; that year, the Tigers, Royals, Brewers and Rays all got there, with all but Kansas City losing 106. The Royals and Orioles would be thrilled, though, to have their car-crash seasons end with 106 defeats—Baltimore in particular. With just 37 wins, a .282 winning percentage on the season and an ongoing eight-game losing skid, the O’s are staring down a possible 46–116 record and threatening to break into the all-time top five for most losses in a single season. Which brings us to perhaps this year’s most absurd number: 52 1/2, or how many games Baltimore trails Boston by in the AL East. This year is going to be a record-breaking one for futility.

Tom Verducci: One: We know Chris Davis of the Orioles is having a very rough year. We know the shift has hurt slow, pull hitters like Davis. But this is ridiculous. On Friday, when Davis singled off CC Sabathia, it was his first groundball hit to the pull side all year. Davis had been 0-for-58 on pulled groundballs.

BEST THING I SAW THIS WEEK: HARRISON BADER'S MAD DASH HOME

By Gabriel Baumgaertner

Maybe the unlikeliest trade of this year’s non-waiver trading deadline was when the Cardinals shipped Tommy Pham—who hit .306 with 23 homers in 2017—to Tampa Bay for a couple of minor leaguers not expected to help the team’s playoff push in 2018. Pham’s departure opened up a spot for Harrison Bader, the speedy outfielder who logged a .265/.338/.400 slash line with six homers, nine stolen bases and—more importantly—excellent defense after making the opening day roster.

The major reason that the Cardinals jettisoned Pham for Bader is because of the 24-year-old’s superb defense, great speed and on-base abilities. If you want an example of why they wanted Bader in the lineup, look no further than his first-inning dash home from second base … on an infield single.

Yes, these are the plays that make “the best fans in baseball” crow about “The Cardinal Way” and “playing the game the right way.” Even though second baseman D.J. LeMahieu never even makes a throw to first base, Bader somehow bolts home two give pitcher Austin Gomber a two-RBI single on a high chopper that barely reached the infield dirt.

The way he did it? Pause the film as soon as the camera tracks the ball off of Gomber’s bat. Before the ball is even close to landing in LeMahieu’s glove, Bader is rounding third base. When a youth coach instructs you to “go on contact” with two outs, this is a perfect example. Head down, arms up and maximum sprint. It’s a perfect bit of baseball.

FOR SOME REASON, THE INDIANS ARE STICKING WITH JASON KIPNIS

By Emma Baccellieri

On Sunday, Cleveland Indians manager Terry Francona announced that he doesn’t anticipate making any changes to his infield configuration for the rest of the season. Jason Kipnis will stay at second, and José Ramírez will stay at third. There’s some fair reasoning behind that decision: Ramírez has been one of the best players in the American League, if not the best player (as Tom Verducci detailed above), so why risk changing anything for him? Despite his demonstrated ability to move around the diamond—with time at second, short and left field in the past three seasons—Ramírez has developed into a player simply too good to uproot. The key question here, though, lies in the opposite of that. Has Kipnis become so bad that he needs to be uprooted?

Kipnis’s entire career has been something of an up-and-down ride, jerked around by injuries. He was an All-Star and down-ballot MVP candidate in 2013, his second full year in the big leagues. But he struggled in 2014, with an oblique problem that nagged all season and a finger injury that required surgery in the winter. He bounced right back, though, and Kipnis was once again an All-Star who recorded MVP votes in 2015. Since then, his performance arc has looked less like a roller-coaster and more like one slow downward slide. After a solid 2016, he was sidelined for much of 2017—first with a shoulder problem that caused him to miss most of spring training and had him floundering at the plate for most of the early season, and then with a hamstring injury. When he finally returned to the roster for the team’s playoff run, he was pushed off second base for the first time in his major-league career and moved to center field.

MLB Players Weekend: Check Out All the Best Cleats

Kipnis has, for the most part, been healthy in 2018. He’s also had the worst season of his career. His .650 OPS makes him the eighth-worst everyday hitter in baseball, and his second-half performance (.585 OPS) has been even worse than his already rough first-half work. So what’s gone wrong? He isn’t striking out significantly more, or walking less. He isn’t chasing more pitches out of the zone, or making contact any less. He’s seeing the shift more often, but he isn’t seeing it quite often enough to explain the drop-off here. And he isn’t grounding out more—in fact, he’s getting the ball off the ground more than he ever has. While the fly-ball revolution might have been an inspiration here, it certainly hasn’t been a solution. In his All-Star 2015, Kipnis hit fly balls for 28% of his contact. That number has risen to 44% in 2017 and 2018, while his success at the plate has dried up. Perhaps the most telling numbers about his decline lie in his handedness splits. Kipnis, a lefty, has actually done better against lefthanded pitching this year. But he’s seemingly completely lost his ability to hit righties, to such an extent that his best performance at the plate is coming against same-handed pitching for the first time in his career. (“Best” being a relative term; he’s still .704 OPS against lefties.)

Cleveland wouldn’t necessarily have to move Ramírez if they wanted to kick Kipnis out of the lineup. They could install utilityman Erik Gonzalez at second, but that would leave Kipnis as the de facto utility guy in his place, and his defense wouldn’t make him a realistic option at short. Or they could try to put Yandy Diaz at the keystone, rather than placing him at third after moving Ramírez to cover second. But he doesn’t have much experience at the position, and it seems clear that the team would rather not do that. Instead, they seem set on leaving the veteran in place—perhaps hoping that he’ll find a way to rebound and make this stretch not a death sentence, but rather just another “down” in an up-and-down career. Cleveland might have a breaking point here, but a .650 OPS apparently isn’t it.

WHAT'S ON TAP: WE CAN'T KEEP OUR ATTENTION AWAY FROM THE A'S ... AND ASTROS

By Michael Beller

Hitter to Watch: Paul Goldschmidt, Diamondbacks

Goldschmidt has been one of the hottest hitters in baseball over the last two weeks, going 21-for-48 with six homers and 15 RBIs. He’s up to .294/.396/.550 with 30 homers and 77 RBI, making this his third 30-homer season in the least four years. That’s all the more remarkable considering that he was hitting .209/.326/.393 at the end of May. Since June 1, he has hit a blistering .351/.444/.656 in 340 plate appearances.

Pitcher to Watch: Aaron Nola, Phillies

In a season that could end with a Cy Young Award, Nola may have just had his best start. He shut down the Nationals last week, tossing eight shutout innings while allowing five hits and striking out nine. Nola is down to a 2.13 ERA and 0.97 WHIP with 169 strikeouts in the same number of innings this year. Some of the shine has come off of pitcher win-loss record, and justifiably so, but Nola still deserves plenty of credit for his 15-3 record this season. The breakout star of the Phillies rotation will take the ball once this week, facing the same Nationals team, and opposing fellow Cy Young contender Max Scherzer, on Tuesday.

Series to Watch: A’s at Astros, Monday through Wednesday

Yeah, we’re going back to this well again. The top of the AL West has produced some of the league’s most dramatic baseball recently, and this series likely won’t be any different. The Astros start this week with a 1 1/2-game lead over the A’s in the division. There are still five weeks left in the season, but this is the final series between these two teams, making it critical to the A’s hopes of getting atop the division. They have put some distance between themselves and the Mariners, though, holding a five-game lead for the AL’s second wild card. The A’s will send Brett Anderson, Edwin Jackson and Trevor Cahill to the mound, while the Astros counter with Gerrit Cole, Charlie Morton and Dallas Keuchel.

TWEETS OF THE WEEK

This might be the winner... pic.twitter.com/1SbJ9SuNXW

— Jon Sciambi (@GoGala__Games) August 26, 2018

Barry Bonds takes BP at a still under construction Pac Bell (now AT&T) Park, Jan., 2000 (pic B. Mangin) #SFGiants pic.twitter.com/Md6xctvtkK

— MLB Cathedrals (@MLBcathedrals) August 23, 2018

How many times each final score has happened in MLB history...

— Jeremy Frank (@MLBRandomStats) August 21, 2018

The 49-33 game happened on June 28, 1871. pic.twitter.com/H0CoITe83b

Rare Color/Pure Beauty-The Splendid Splinter (from the Flagstaff Films baseball home movie archive) "You get your power not so much from the wrists or the arms and shoulders, but from the rotation of the hips into the ball." Ted Williams, from The Science of Hitting. pic.twitter.com/OxsSzWWe40

— Flagstaff Films (@flagstafffilms) August 25, 2018

Zack Greinke, 69mph Curveball. pic.twitter.com/4viTwce5yy

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) August 26, 2018

FROM THE VAULT: CELEBRATING A CENTURY OF THE KID

By Connor Grossman

The late, great Ted Williams was born 100 years ago this Thursday. The Kid passed away in June 2002 and will always be remembered as one of the best to ever play the game. Perhaps the crown jewel of his unparalleled baseball résumé, Williams was the last player to hit .400 in a season. No one has cleared the barrier since he batted .406 in 1941. Today's focus on maximizing launch angle (increasing both home runs and strikeout totals) doesn't inspire confidence that the mark will apparoached anytime soon. He had one of the sweetest swings you'll ever see.

You know about Teddy Ballgame's sweet swing, but how about his skill with a hook and bait? SI went fishing with Williams in 1967 and produced this memorable piece by John Underwood.

Enjoy the excerpt below and find the full piece here.

***

The Kid drives much the way he used to get ready to hit a baseball. When he was waiting in the on-deck circle or standing at the plate, he could not be still. He moved his arms and jerked his shoulders, pumped his bat, squeezing the handle as if to wring out the reluctant base hits. When he drives a car he is no less convulsive. He is a highly animated conversationalist and sometimes finds it necessary to take both hands off the wheel to make a point. He drives with his knees. He does not drive slowly.

To fish with Williams and emerge with your sensitivities intact is to undertake the voyage between Scylla and Charybdis. It is delicate work, but it can be done, and it can be enjoyable. It most certainly will be educational. An open boat with The Kid just does not happen to be the place for one with the heart of a fawn or the ear of a rabbit. There are four things to remember: 1) he is a perfectionist; 2) he is better at it than you are; 3) he is a consummate needler; and 4) he is in charge. He brings to fishing the same hard-eyed intensity, the same unbounded capacity for scientific inquiry he brought to hitting a baseball.