Meet Your New Favorite Player: Twins Utilityman Willians 'El Tortuga' Astudillo

A favorite player is meant to be specially individual—the most personal decision that a fan can make, if not the most sacred—but the methodology behind selecting him is the same for almost everyone. Oh, sure, the specifics differ, but there’s a clear through-line here; the core nearly always holds constant. A favorite player must be different. The easiest way for him to be different is to be very good. Maybe he’s very good in one particular area, or maybe he stands out the most among the “very good” on a favorite team, or maybe he’s just very good, period. Maybe he’s Mike Trout. This is the most obvious way to determine that a player is different enough to be deemed a favorite, and this is why there are thousands of kids wearing jerseys with Mookie Betts’ name on the back rather than Blake Swihart’s.

But there are other ways to be different. Maybe it’s his batting stance. Maybe it’s the way that he can occasionally be seen talking to himself alone in the outfield. Maybe it’s his haircut, or his high socks. There are infinite ways to be different. But there’s one player that’s more different than any other right now, and possibly more different than any in quite a long time: Minnesota Twins rookie Willians Astudillo, the weirdest player in baseball and the perfect favorite player.

You do not have to look far to see Astudillo’s most obvious difference, because all you have to do is look at him. His build can generously be described as “sturdy” and less generously described as “stubby,” all squat and densely packed. Astudillo is 5’ 9” and 225 pounds—or, at least, he’s listed as such—which means that he doesn’t look too much like a baseball player, let alone a professional one. Of the thousands and thousands of players with height and weight data listed on Baseball-Reference, there is just one other who ever came in at 5’ 9” and 225 pounds. (Alberto Callaspo.) By virtue of his body alone, then, Astudillo is noteworthy. When he runs the bases, he becomes a meme. “I just wanted to show that chubby people also run,” he says after the game. He’s a baseball player, performing an unremarkable baseball activity. And yet, because it’s him, in a body that would be utterly ordinary in any other setting—exactly what makes it so unordinary, here—it does feel like something remarkable. He’s different.

Size doesn’t measure speed. pic.twitter.com/r13jphlD9j

— MLB (@MLB) September 13, 2018

Astudillo may not look much like your average baseball player, but to the extent that he does, he looks like a catcher (which he is—most of the time, but barely). A quick glance at his game log may leave you thinking that he’s a prototypical utility player, with all the flexibility and sprightliness that usually entails. In 20 major league games, Astudillo has been behind the plate scarcely half the time. Otherwise? He’s filled in at second base, third base, left field, and he’s even done a brief stint in center. And, oh, yes, he made a pitching appearance, too. (Though being a position player on the mound didn’t leave him looking quite as out of place as did being a 5’ 9”, 225-lb. guy in centerfield.)

The Twins are not being cute here, messing around in the desperate moments of a losing season. They’re just using him as he’s always been used. Astudillo played five different positions this year at Triple-A, just as he played five different positions in his first year in organized ball in 2009. Over nine seasons at various levels, he has played every single position on the diamond. That doesn’t mean that he’s played all of these positions exceptionally well, but the power of that fact does not depend on the quality of his defense. It depends on Willians Astudillo, who does not resemble any type of baseball player, earning the right to be trusted as every type of baseball player. He’s different.

So—he’s a chubby rookie with some surprising defensive versatility. A solid start for any round of build-a-favorite-player! But Astudillo has far more to offer. Start by looking at his statistics from the minor leagues. The first thing to notice about this record is that it is not the record of a prized prospect, or of any prospect. There’s a jumble of clubs here—Phillies, Braves, Diamondbacks, Twins—passing him around as he slowly made his way from rookie ball on up. He took nine seasons to play his first game in the big leagues; Astudillo, 26, is nearly two years older than the average player who debuted this season. There is nothing remarkable about this path, trodden by countless young men who get stamped with the label of anonymous organizational filler. But there’s something quite remarkable about what he’s done on this path. Astudillo, at every single level, has maintained a weirdly intense approach to plate discipline. He does not walk, and he does not strike out. He has never wavered in that austerity. As baseball becomes increasingly centered on the three true outcomes, Astudillo seeks his truth elsewhere.

Over 220 plate appearances in his first year of organized ball, Astudillo walked eight times and struck out ten, with just one home run. Those figures were markedly low (3.8% walk percentage, 4.8% strikeout percentage) but it was rookie ball, and he was just a teenager. A weird profile might be nothing more than weird, a blip that could be smoothed out with coaching and experience in a season or two. But Astudillo’s weird profile was not a blip—indeed, it was the opposite. He offered only a very slight variation on that performance for the next year, and the year after, and the year after. In his nine minor-league seasons, he never posted a walk or strikeout percentage above 6.8%. From 2,155 total plate appearances entering this year: 75 walks, 67 strikeouts, and 17 home runs. Those three outcomes are baseball’s enlarging heart, at every level. In 92.6% of his plate appearances, Astudillo did something else.

Those numbers made him something of a cult darling among the corner of the baseball world that is inclined to notice the minor league plate discipline of a non-prospect. But that’s just the minors, you might say; the show is something different. Sure! It is. Astudillo has gotten more extreme in his brief big-league exposure. In 61 plate appearances, he has walked once and struck out twice. That’s it: 1.6% walk percentage and 3.3% strikeout percentage.

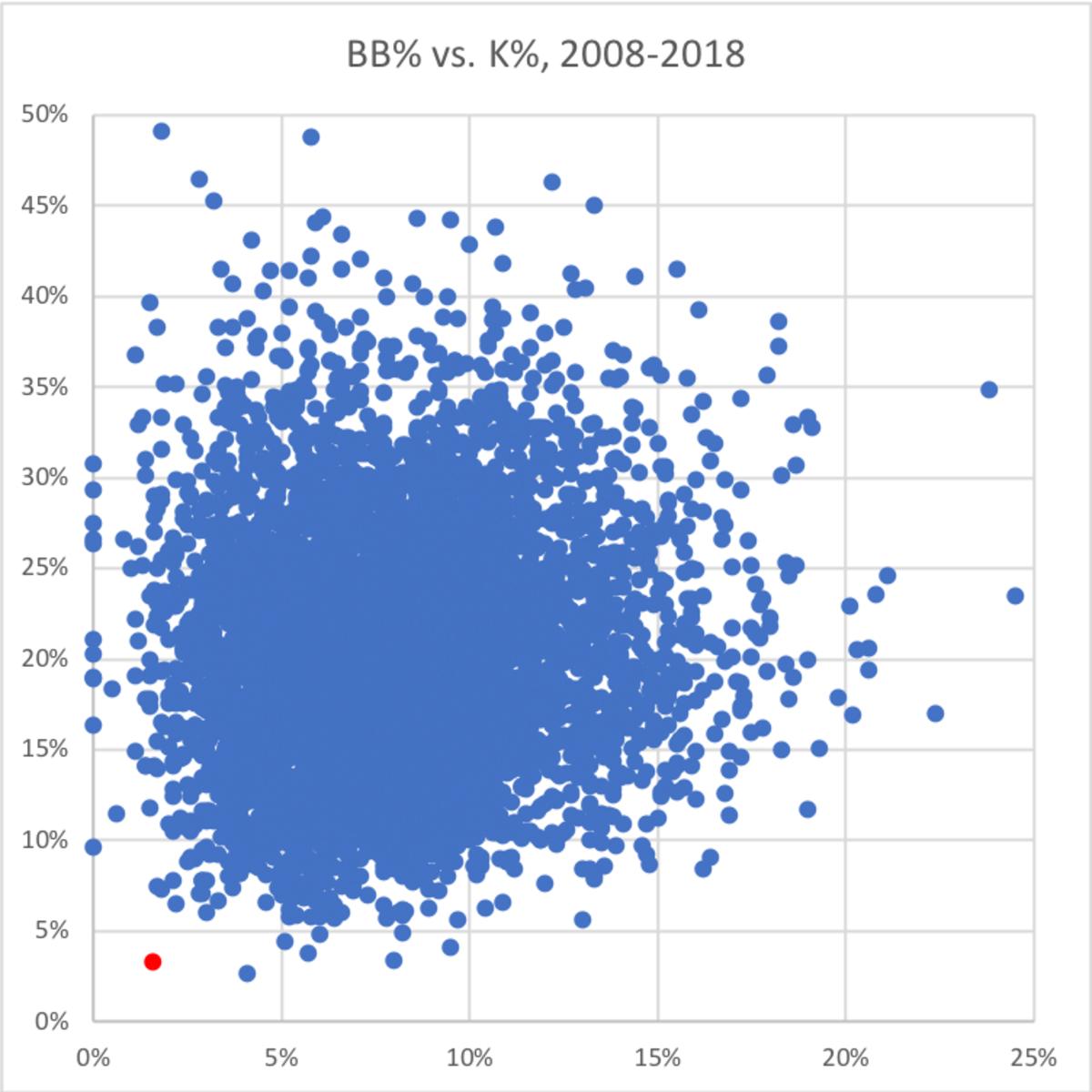

Just how much does he stand out? Here’s every batter’s season from the last decade:

Astudillo’s highlighted in red here, but he was obvious, anyway. With 5,572 batter’s seasons, thousands of them clustered in the same dense center, Astudillo’s 2018 is an outlier unlike anything that baseball has seen in recent years.

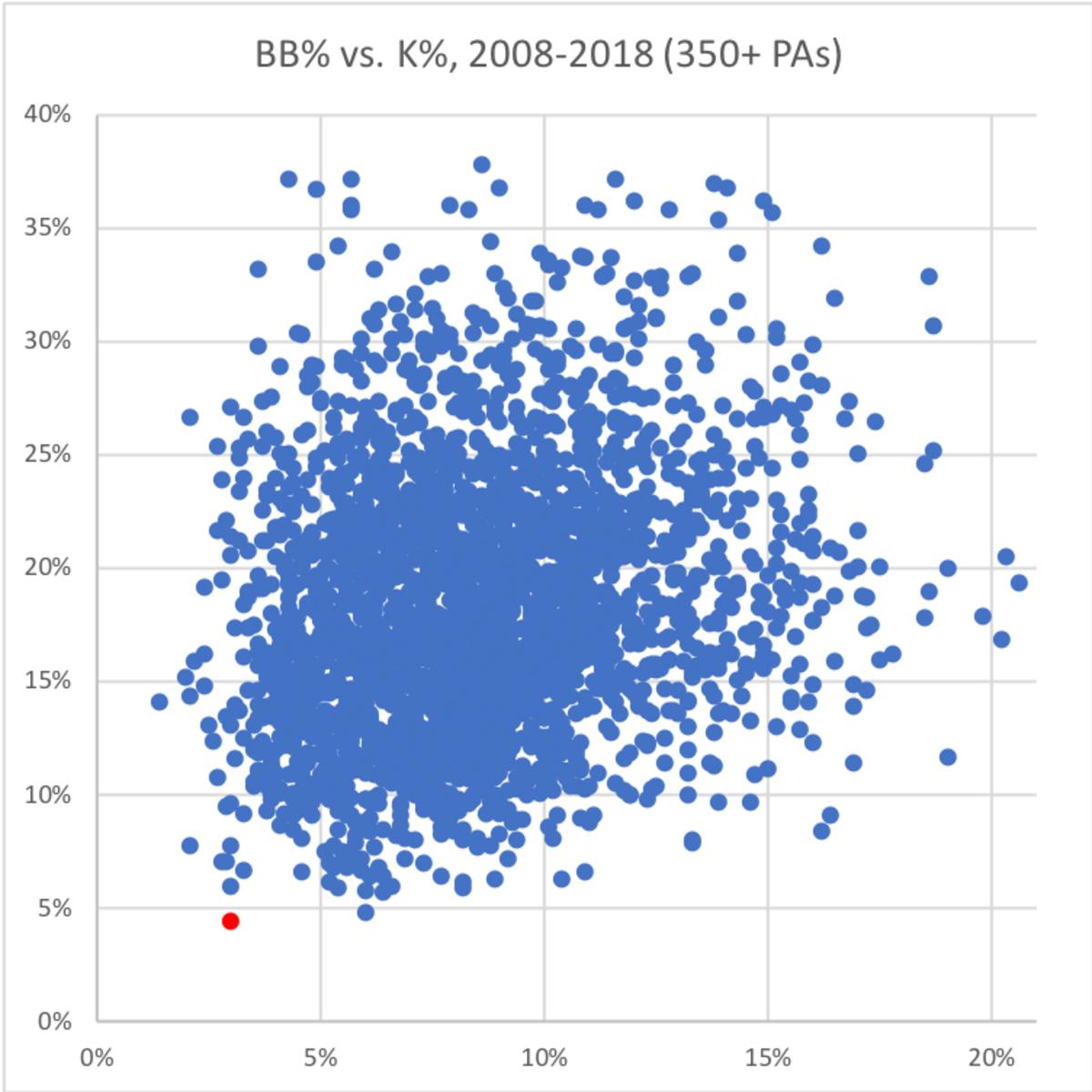

The minimum number of plate appearances for the seasons in the plot above is fifty. That’s a low cutoff, just a fraction of what’s necessary to qualify for the batting title and nowhere near what’s necessary for these statistics to stabilize. But Astudillo’s time in the major leagues thus far has been so brief that it only makes sense to include other partial seasons in a comparison. If you wanted to throw those out, though—if you wanted to get rid of the small sample noise, and look at the context for a potential full season of Astudillo? It’s not a perfect solution, but let’s combine Astudillo’s 2018 Triple-A and major-league numbers. That’s not exactly rigorous, but tis profile has only shown slight changes from one level to the next, and so it works well enough for getting a rough sketch of how the landscape might look here. Here’s what that looks like, stacked against every major league batter’s season from the past decade with at least 350 plate appearances:

Over the last ten years, no hitter has posted a strikeout and walk percentage below 5%. But Astudillo did that in seven of his nine minor league seasons, and he’s doing it in his first major league one. He’s different—radically, weirdly, delightfully different.

Astudillo’s game has shown one key development this season. While his walks and strikeouts are as rare as ever, he’s invested a bit more in the third true outcome—the home run. In Triple-A, he hit 12. (His previous high? 4.) In his brief big league stint so far, he’s already hit three, which is, yes, as many walks and strikeouts as he’s had combined. And beyond the long ball, he’s been thriving in the majors. His .820 OPS is a head above where it was in Triple-A, lately making him one of the most productive members of Minnesota’s offense. He is, obviously, a free swinger—going on more than half of the pitches that he sees—but he connects on almost all of them. His 91.9% contact rate is one of the highest in baseball. Astudillo’s approach, odd as it is, has always worked for him; now, he’s proving that it can work in the majors, too.

He hasn’t yet been in the major leagues long enough to make any definitive judgments on his talent here, and it’s still unclear if there will be a space for him on the roster next year. But Astudillo is a marvel—right now, on his own merits, in this small sample size—whatever the future may hold. Beyond all this, his file holds plenty more favorite-player-fodder. There’s his no-look pickoff move from this spring, and his hidden-ball trick from this summer. There’s the fact that his brother, Wilfred, and cousin, Wilfran, are in organized ball, too. There are all the tiny habits and routines and details that make up a player’s game. But, mostly, there is the fact that he’s different—that he looks like, literally, no one else in baseball.