What If Bucky Dent Didn't Hit that Legendary Homer Over the Green Monster?

The following is excerpted from the book Upon Further Review: The Greatest What-Ifs in Sports History by Mike Pesca. Copyright ©2018 Twelve by Hachette Books. Reprinted with permission of Hachette Book Group, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

Kojak called as soon as the games ended.

He’d already checked the train schedules and everything. We’d meet in front of the high school at 7:30 the next morning—Kojak (got a buzz cut in fourth grade), Fonzie (said “Whoaaaaaa” unironically once in sixth grade), the Cannon (JV soccer coach complimented a penalty kick), and me, Bean Juice (no one knew why, even the kid who stuck me with it in fifth grade). First bell was 8:23, but we’d tell our parents we had a Spanish club meeting or jazz band rehearsal or whatever.

It was a ten-minute walk to the Pelham train station. Half-hour ride on the 8:07 to Stamford. Half-hour wait for Amtrak. Three and a half to Boston. The T to Kenmore. Scalp four tickets and find our seats in the belly of the beast in time for first pitch at 2:30. The Yankees would win the one-game playoff in Fenway—and then a third straight American League title and second straight World Series—and we would book back home, a Murderers’ Row of lies tucked in the pockets of our Levi’s cords. Our parents wouldn’t know a thing.

Order your copy of SI's Red Sox-Yankees commemorative issue now!

And even if they dragged it out of us—if we missed a connection and evening turned to night, or night turned to midnight, and they called each other, or the cops—how could they be mad? They were the enablers. Bought us yearbooks and plastic helmets and pennants that still hung on our bedroom walls. Took us to Bat Day and Cap Day. Dropped us at Dyer Avenue and let us ride the 5 train, covered in graffiti like some Christo installation, to Grand Concourse and switch for the final two stops uptown to the Stadium. Spied us through the kitchen window focused like monks perfecting the stances of our preteen idols: Horace Clarke’s legs spread wide as the Lincoln Tunnel; Roy White’s pigeon-toed precision; Bobby Murcer’s looping, laconic practice swings. Watched us lob Folly Floaters against the garage, which we would then deploy on the stickball court.

But those old Yankees sucked. These new Yankees ruled. Chambliss in ’76, tears of joy, my immigrant father in his La-Z-Boy, smoking his pipe, unaware that my life was, at that precise moment, at its apex. Then ’77, Reggie signing for the unholy sum of $3 million over five, “the straw that stirs the drink,” the tête-à-tête with Billy in the dugout. Son of Sam and the blackout. But also the young Guidry, Mick the Quick, Thurman, Sparky, and Sweet Lou. I was there for Reggie’s three home runs in the sixth and final game of the World Series at the Stadium. That’s a lie—I was there for the first two. The family friend who scored the tickets wanted to beat the traffic, so I heard the roar of number three as we walked to the garage.

I never forgave him, or my oldest brother, who lived in the city and stayed behind and delivered to me a hunk of sod he’d ripped from the trampled field, as if that would fill the bottomless hole in my soul. (I planted it in the backyard. It died.) But we won, the Yankees won, and we’d be champs for a long time. I was sure of it. We were all sure of it. Even during the Bronx Zoo of the following summer, we were sure of it. It was just theater. Reggie, in July, pissed at being asked to bunt with the winning run (Thurman) on first, fouling off the first pitch, blowing off the new sign and bunting foul twice more; Billy losing his mind and demanding that George suspend Reggie for the rest of the season (the rest of the season!); the team falling fourteen games behind the Red Sox at the end of the day; the tabloids maxing out on point sizes. Six days later, Billy said of Reggie and George (respectively): “One’s a born liar and the other’s convicted.” And then resigned in tears.

The thing everyone forgets? Between Reggie bunting and Billy self-destructing, the Yankees won all five games they played. The fourteen-game deficit was down to ten. By September 1 it was six and a half. And on the 10th of September, Year of Our Lord 1978, the Boston Massacre was in the books—the greatest sweep ever: 15–0, 13–2, 7–0, 7–4—and the New York Yankees and the Boston Red Sox were tied for first place in the East Division of the American League of Major League Baseball. We went up three and a half on the 16th and should have locked the damn thing down. I can’t say the Yankees blew it. They won six of their last eight games. Boston won all eight.

On the final day of the regular season, Luis Tiant shut out the lowly, tatterdemalion Blue Jays while Catfish lost to Cleveland.

* * *

We made it without a hitch. Our jowly European history teacher, Mr. Smith—Froggy—wondered what the hell we were doing at school so early, but he didn’t break stride. At the station, Kojak and Fonzie scanned for commuting dads while the Cannon and I bought tickets. We told the conductors we had the day off—teacher meetings, Kojak said. Upon arrival in Boston, I found a pay phone and called my other brother, who was on an eight-year plan at M.I.T. He asked what the hell I was doing here, and then said he was too stoned to join us.

Fenway Park was a dump—even 15-year-old me knew that. But I understood that it was mythic, too, that “lyric little bandbox of a ballpark,” in Updike’s words that I wouldn’t read for another decade. It was impossible to deny the history of Fenway, just as it was impossible to deny the history of the Stadium (the original, not the renovated one). Fisk waving that home run fair in ’75 sure was something—especially because they lost Game 7. And the rivalry had turned feral: Munson and Fisk brawling at home plate in ’73; Chambliss getting hit in the arm by a dart—an actual dart—thrown by a fan in ’74; Piniella and Fisk and then Nettles and Lee brawling in ’76, Lee separating his shoulder. Sprinkle that on your pancakes, Spaceman.

We paid 20 bucks apiece for the seats. Face was $5.75. That was nuts, but we were teenagers in Yankees caps, easy marks. Our cash reserves from a spring and summer of mowing and umpiring were nearly depleted. But we’d bought round-trip tickets, and could survive on hot dogs and adrenaline. And holy hell! third row, right field, smack next to the Pesky Pole. All that green—the seats, the grass, the Monster. It was beautiful, hell and heaven all at once. We were going to see history.

Just not the history we expected.

I’m switching to the present tense here because, forty friggin’ years on, it feels every bit like right this second. Guid—24–3 on the season—is pitching. For Boston, Mike Torrez; after less than a year in pinstripes, he and the World Series ring we gave him defected in free agency. Advantage us. But Yaz homers in the second and they scratch out a run in the sixth. Two-zip Boston; they have as many runs as we do hits.

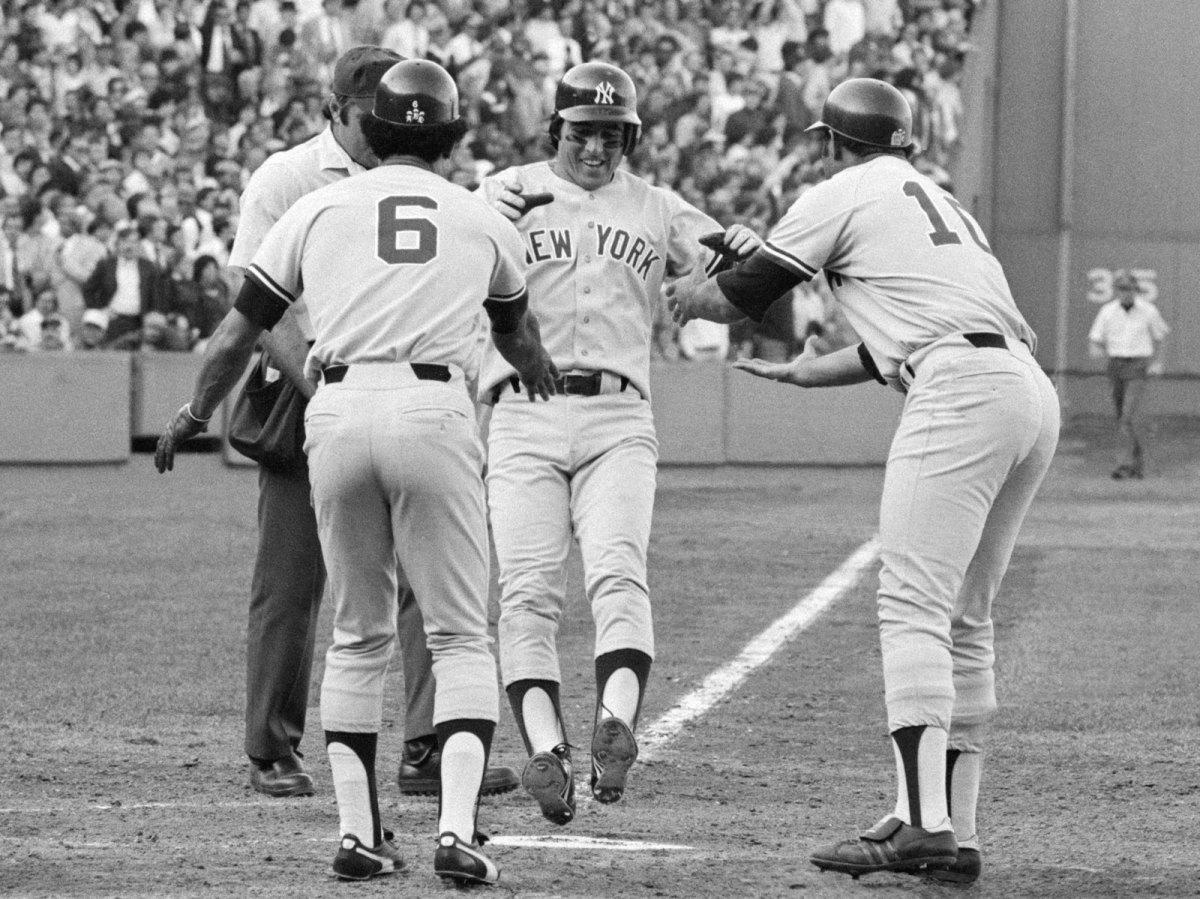

Then the seventh, so full of promise. With one out, Chambliss singles to left and White singles to center. Jim Spencer, batting for Brian Doyle, flies out. Two down. Bucky Dent, choking up like an undersized Little Leaguer (me), takes ball one. Flail and a miss, one-and-one. And then Bucky skies one down the left-field line. Like Fisk three years earlier, Dent tries to will the ball fair. Wave. Wave. Wave. But it doesn’t cooperate. Strike two. And then he takes strike three. Mighty Bucky has struck out.

But Rivers walks to open the eighth and Munson lashes a double off the Monster, scoring Mickey. Then Reggie, not suspended for the rest of the season, hits a mammoth homer to straightaway center off Steamer Stanley. Just like that, we’re winning, 3–2.

Through the first seven innings, the score ensured we could avoid the attentions of our hosts. Munson’s wall ball and Reggie’s blast ended that. We’ve been whooping and bouncing and low-fiving since—and the natives have noticed. Our conspicuous group hug after Reggie’s homer triggered a cascade of peanuts. When Goose K’s Butch Hobson to end a one-two-three eighth, and Kojak screams, “F*** YEAH! LET’S GO BOMBERS!” the locals have had enough. Co-opting our “Boston Sucks” chant—invented in the Stadium bleachers a year earlier—they serenade us with a chorus of “YANG-KEES SUCK!” and identify us with a sea of index fingers. It was, in retrospect, probably a bad idea for me to reply with a different digit.

Dwight Evans flies out to left to start the Red Sox ninth. But then Gossage walks Boston’s Dent-like shortstop, Rick Burleson, bringing to the plate Boston’s Dent-like second baseman, Jerry Remy. Remy is five-nine, one-sixty-five. Even Bucky has more home runs (four) that he does (two).

Occasionally now, in a conjoined display of masochism and nostalgia, I’ll watch the at-bat on YouTube. “There’s the tying run there at first base,” Bill White tells his WPIX viewers. “One out, Jerry Remy’s the batter.”

The lefthanded Remy takes a ball, then fouls the next pitch off of his right instep. The Red Sox trainer sprays it with ethyl chloride to numb the pain. “That’s only temporary relief,” White says. “Sometimes I wonder whether it’s relief at all.”

In right field, our hearts are racing, but we are quiet as parishioners, aware that things might not end well, and that we are outnumbered by a lot.

“The count’s one and one,” White says. “One out and one on, the Yankees lead at 3-2 in the ninth inning here at Fenway. … Deep to right! Piniella … can’t see the ball! He’s back to the wall! It’s … off of Piniella’s glove and … off the Pesky Pole and into the seats! It’s a home run! And the Red Sox win! … The final score, the Red Sox four, the Yankees three, and the Red Sox win the 1978 American League Eastern pennant.”

Oh, look, there I am: the ball deflecting off Piniella, doinking the Pole, bouncing off the head of some Masshole—they didn’t call them Massholes back then—right to me. Easiest catch I ever made. I go fetal, and the pummeling begins. A fist to the kidneys, meaty male hands twisting my wrist and prying my fingers. Kojak and Fonzie pull off Massholes; the Cannon plays human shield. When the Bostosterone abates, I stand up, raise the ball aloft like the severed head of a vanquished soldier, and in the rawest, most impulsive and animalistic moment of my young life, wind up and hurl that piece of garbage whence it came. The ball, signed by AL president Lee MacPhail, cuts a slow, graceful arc through the late-afternoon sun before skittering to a stop near second base. I had an arm.

Kojak, Fonzie, the Cannon, and I roar in celebration of my audacious taunt. I’m Timmy Lupus at the end of The Bad News Bears: Shove it straight up your ass, Boston. And then we spy the gathering army and bolt for the turnstiles. My beloved NY cap is ripped from my beloved NY head. The Cannon swats away double-barrel birds thrust in his face. A full cup of beer showers the Fonz.

We sprint up Landsdowne Street, a menacing chorus of “YANG-KEES SUCK” ringing in our teenage ears.

Hub fans bid kids adieu.

* * *

We made it home, were found out—Kojak’s dad saw me catch the homer; oops—and were grounded for the rest of October, during which, of course, the Sox swept the Royals in the ALCS and the Dodgers in the Series. Covering it for the Baltimore Evening Sun was a 25-year-old son of Groton, Mass., named Dan Shaughnessy. Forget the Globe and the Herald. Shaughnessy’s Game 4 gamer is the one that endures:

BOSTON—Was there ever any doubt?

Sure, there were bumps on Jersey Street, slogs as muddy as the original Fens, ifs piled high as the Green Monster. If Ted had played in ’46, if Lonborg hadn’t faded in ’67, if Spaceman hadn’t blistered in ’75. If, if, if.

You can bury the ifs and the almosts under the Citgo sign. Ask your parish priest to say a prayer for the departed past—and then go buy a round at the Eliot. The Boston Red Sox are champions of the world.

Not that the Fenway Faithful didn’t believe. It’s not as if the Red Sox were cursed. It’s not as if the fate of the franchise fate was sealed a long, long time ago, as the poet said, when Harry Frazee of Boston traded Babe Ruth of Baltimore to the Yankees of New York.

They don’t write books about curses. That’s not how sports work. That’s not how life works. What’s 60 years between titles anyway? Not even a lifetime.

Shaughnessy was hired the next week by the Globe. He broke the news of the trade— bitter Reggie straight up for bitter Jim Rice—and covered the dynastic second, third, and fourth titles in ’79, ’80, and strike-shortened ’81, wooing readers and players alike with his positivity and goodwill. Then, “tired of all the winning,” Shaughnessy announced he was leaving the Globe to write fiction. (His dystopian 1984 novel, The Curse of the Bambino, depicted a world in which the Red Sox never—ever—win the Series. Reviewing the book in the Globe, Boston superfan Stephen King called it “a tale of horror too unspeakable to commit to print—and one too preposterous to credibly imagine.”)

The Miracle of Pesky’s Pole, as it was dubbed, transformed the penurious and racist Red Sox ownership like some baseball Christmas Carol. Boston spent truckloads of money and signed or traded for more black players in the next three years than it had in the previous twenty—Joe Morgan in ’79, Dave Winfield in ’80, and, Reggie, re-signed, in ’81. “Twenty-five guys, one Green Line car,” Jackson proclaimed. The Red Sox healed the wounds of a divided city.

Then, at the peak of their power and leverage, the Yawkeys overreached, as you knew they would. Complaining about undersized, rat-infested Fenway and threatening to move to Hartford, the owners pried from the city that sweetheart deal: the sports megaplex in Southie, one stadium for baseball, one for football’s laughingstock Patriots. The Red Sox played their final game in Fenway on October 6, 1985, and moved into Prudential Stadium on April 14, 1986. Just-retired Jerry Remy threw out the first pitch.

I know, the bastards won it all again that year, thanks to World Series MVP Bill Buckner’s 13-for-32 batting (that’s .406 for the historians out there) and his slick fielding at first base. But Shaughnessy was right—all that winning, and that discordant big hatbox of a stadium, 330 down the lines, 400 to dead center. There was nothing lyric left to love, and, after ’78, ’79, etc., nothing for fans to moan about the way they once did. The Red Sox were a corporation, as dominant and as personable as IBM.

The wrecking ball took its first cut at Fenway on the day after the ’86 Series, stirring the poltergeists below. And in 2016, on the thirtieth anniversary of Boston’s last championship, Shaughnessy emerged from the basement office of his Newton home, reconsidered his ’78 deadline proclamation, and made a triumphant return to nonfiction sportswriting with the bestselling TheCurse of the Green Monster.

And us? Well, with hindsight like Ted Williams (20-10), I maintain that the Yankees’ loss on October 2, 1978, was a blessing. Reggie’s departure let Thurman stir the drink. Munson didn’t win another ring, but those next four All-Star seasons led to that touching Cooperstown ceremony where he sprinkled a vial of Stadium dirt on his rumpled suit. Billy left the torment of the Bronx for good. Managing in Milwaukee, he found a therapist (who would become his third and final wife), stopped drinking, started meditating, and was a beloved mentor to scores of young players: “Uncle Billy,” they called him. When Steinbrenner hired some Whitey Bulger babbo to plant cocaine in Reggie’s Fenway locker in ’84, and Bowie Kuhn, in his final act as commissioner, banned the Boss from baseball for life, the Bronx actually cheered.

Yeah, we have our own curse, the Curse of Pesky’s Pole. It’s been forty years for us, and we’re still waiting. (Those singsong Fenway chants in Boston of “NINE-teen SEVENTY-seven!” do sting.) But there’s honor in futility, joy in the hunt. The Yanks are lovable, sometimes losers, sometimes not, and who could ask for more? No one can take away those ALDS appearances in ’96 and ’97, when that Jeter kid looked like the real deal. (Shame about his knee; he never should have gone skiing with that model.) And the close call in 2009, when “The Captain,” True Yankee David Eckstein, gritted the plucky Bombers all the way to Game 6 of the ALCS. Good times.

Without the Pole, the Yankees wouldn’t be the Yankees. Without the Sisyphean struggle, without the walk in the desert, there’s no Sons of Kevin Maas, the online bar where Kojak, the Cannon, Fonzie, and I relive our youth, politely bemoan the present, and wait ’til next year. There’s no Good Vinnie Hunting, the movie about Yankees fan and Hunts Point Meat Market janitor Vince Hunting (Leonardo DiCaprio), whose math genius is unlocked by a shrink at Columbia (Lorraine Bracco) who missed Game 6 in ’77 because she had to “see about a guy.” And there’s no way a kid from Great Neck who turned nine a week B.R.—Before Remy—experiences enough heartbreak to make New York a journalistic totem of obsession and pathos, and to reinvent sportswriting. If the Yankees somehow manage to win it all again, Will Simons just won’t be Will Simons anymore.

Don’t get me wrong—I’m not happy about ’78, whatever good it spawned. But tragedy is memory, too, and I’m grateful for that moment seared in my consciousness. I can still smell the beer on the Fonz’s windbreaker, and still the “F*** YOU”s echo in my brain. I can feel Jerry Remy’s batted ball carving the Back Bay sky, and taste the sweet exhilaration of my bold rebellion in front of 32,925 people, myself included.

I’m going to switch to the present tense again for this last little pentimento, or whatever it is (to quote Salinger), because, though it happened a couple of years ago, it too feels like today. My son is 15, like me back then. Time for some closure. I take him to a Red Sox-Yankees spring-training game in Fort Myers. (You know where those corporate shills play? JetBlue Park at Fenway South, I kid you not.) We get to the ballpark early, before batting practice even. Remy, who does TV for the team, is on the field chatting with Pedroia, who’s playing catch with Bogaerts. “Jerry!” I shout. “Over here!”

I’ve waited four decades for this moment, and I’m prepared. I tell him the whole story. Skipping school, the train to Boston, the seats in right, catching his homer and heaving it back. He laughs and thanks me for the ball—says he always wondered who threw it, never saw anyone do that before, always assumed it was an act of kindness by a Red Sox fan.

Not so, Boston. It was a primal howl born of crushing disbelief, a delirious response to an unthinkable horror, a spontaneous, cathartic release. From my backpack I pull a print of the black-and-white photo that ran on Page 1 of the Times the next morning—Piniella, the Pole, the ball, me—and extend a Sharpie.

“Jerry F****** Remy,” he writes, and winks at me and walks away.

Stefan Fatsis is the author ofWord Freak, A Few Seconds of Panic, and Wild and Outside, and is a cohost of Slate’s sports podcast, Hang Up and Listen. He listened to the Yankees-Red Sox playoff game on a transistor radio during junior varsity soccer practice in Pelham, N.Y., and sprinted around the field in rapturous glee after Dent’s homer.