Nine Innings: Best World Series Sleeper Pick, Ranking Fall Classic Matchups and Startling September Numbers

BREWERS' BULLPEN PAVES THE WAY TO A LONG OCTOBER IN MILWAUKEE

By Tom Verducci

The best sleeper pick to win the World Series began this season as a 55-to-1 shot to do so, has the third longest current championship drought, and ranks 22nd among major league payrolls. And if the Milwaukee Brewers do win it all, it will be the ultimate confirmation that the baseball you grew up with is officially dead.

The Brewers are built for today’s brand of baseball and they are built for October. When pundits bemoaned how Milwaukee did not trade for frontline starting pitching mid-season, it doubled down on positional and bullpen depth.

The Brewers reached this point because manager Craig Counsell is the most aggressive manager in the history of postseason teams. No team ever got this far by going to its bullpen so early and so often. And because general manager David Stearns gave Counsell a loaded chef’s kitchen of bullpen options—specific tools for the exact right tasks—Counsell has done so without wearing out any of his best options.

Oh, and it doesn’t hurt that Christian Yelich is the 1967 version of Carl Yastrzemski and that this team doesn’t sacrifice athleticism for power. It is the only team in the National League with 200 homers and 100 steals and ranks first among all playoff teams in Defensive Runs Saved.

One-run records can be fluky, but this much is certain: the Brewers are comfortable playing them. They are 33-19 (.634) in games decided by one run. Go ahead and make the postseason bullpen games, as they tend to be. The Brewers are 41-21 (.661) in games decided by relievers.

To appreciate the Brewers, the first thing you have to do is put away your vinyl records and forget about what you learned about “winning baseball”–you know, rely on starting pitchers that go deep into games and play small ball to win close games. Because bullpens are so deep with such powerful arms, the gap never has been greater when it comes to the choice of getting length from a starter or going to a fresh bullpen arm. The Brewers and A’s have leveraged this gap better than any team.

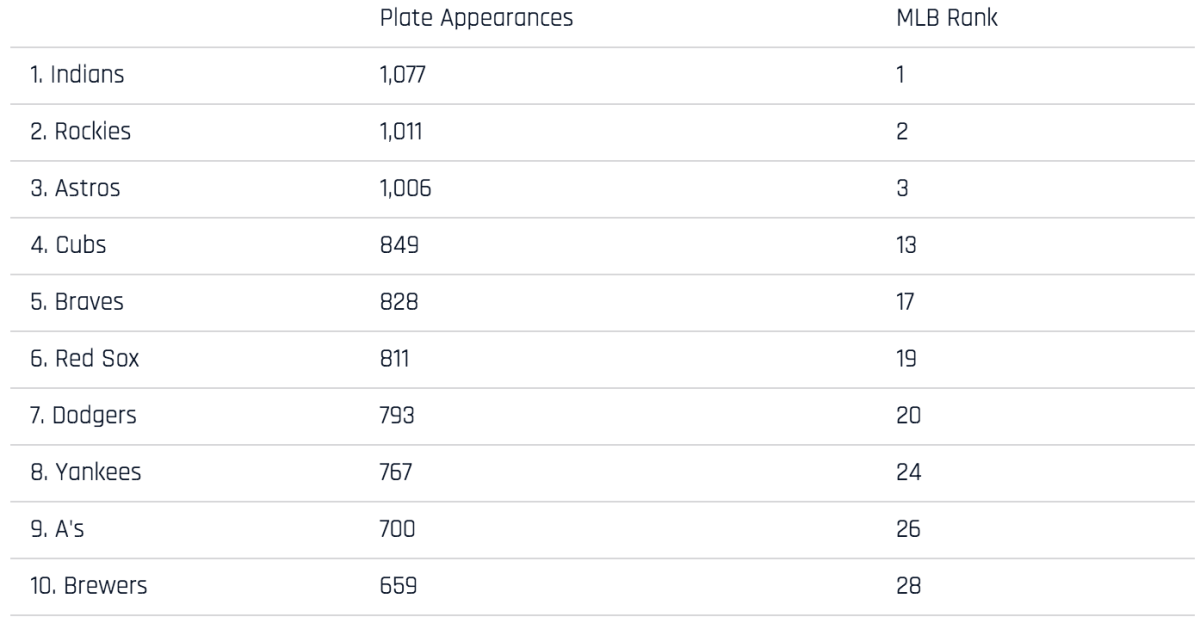

First, take a look at this: the list of playoff teams ranked by how many times their starters faced a batter for a third time (entering Sunday):

Starter Facing Batter Third Time, 2018 Playoff Teams

What is striking is not just that the Brewers are last … Or that their starters have faced a batter for a third time the least in franchise history—including strike-shortened seasons … Or that they faced batters a third time about half as often as their starters did in 1982, the only time the Brewers reached the World Series (1,229).

What’s also evident is that you don’t need length from starters to win. More playoff teams (six) rank in the bottom half of extending starters than in the top half (four).

It’s not that Milwaukee’s starters are terrible; they rank 11th in baseball in ERA (3.96)–just behind Cubs’ starters. It’s just that they are the best at leveraging bullpen this much:

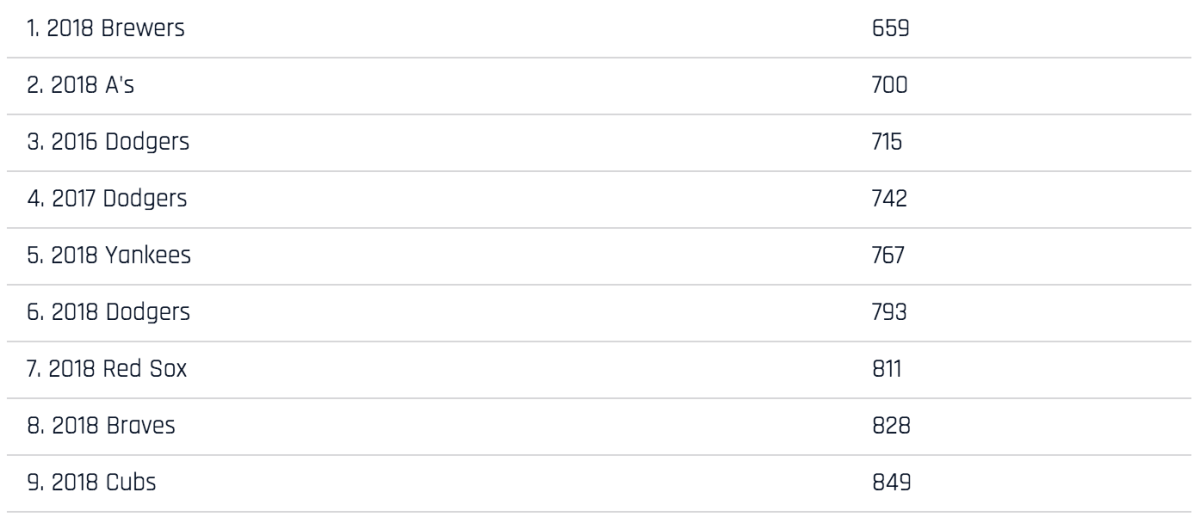

Fewest Batters Faced Third Time Around, Playoff Teams (Full Seasons)

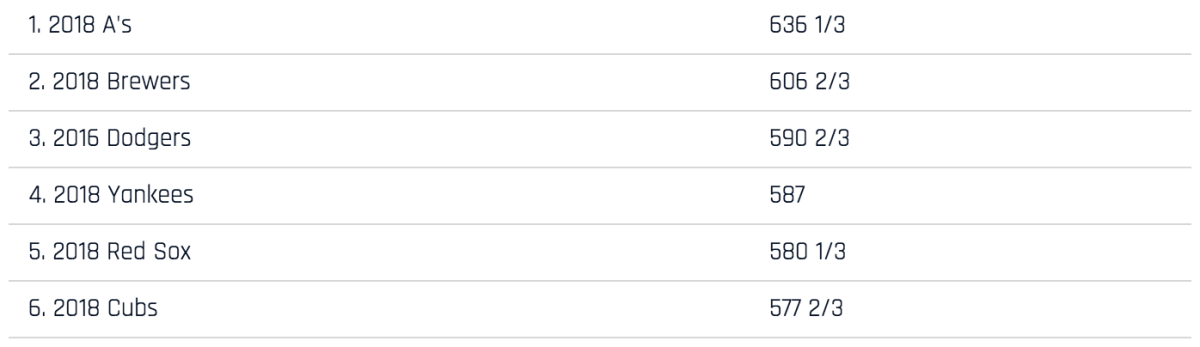

Note that seven of the top nine such seasons occurred this year. If raw innings are your bag, it’s the same story. The A’s and Brewers are the first teams to reach the postseason by asking their relievers to eat up more than 600 innings. Five of the top six all-time bullpen workloads for playoff teams occurred this year:

Most Innings by Bullpen, All Playoff Teams

It’s not just about having many relievers, it’s also about how you use them, and Counsell showed his mastery in the three-game sweep in St. Louis last week. He went in determined not to give the Cardinals’ two best hitters, Matt Carpenter and Marcell Ozuna, comfortable at-bats. He managed to gain the platoon advantage over them in 68% of their plate appearances, including having reliever Dan Jennings start one game to face Carpenter only. It worked. Carpenter and Ozuna went 1-for-13 against like-sided pitchers and the Brewers swept the series.

Every option Counsell has is a good one–as long as he matches up the right pitcher on the right batter. Here are his specialists:

The Secret Weapon: Corbin Burnes

Burnes, a righthander, was developed as starter, so he is a multiple-inning option who pitches out of the windup. Platoon-neutral relievers (they get out lefties and righties) are gold because you don’t have to match up. Burnes is one of them. His fastball/slider combo is actually tougher on lefties (.170).

The Matchup Lefties: Dan Jennings and Xavier Cedeno

It’s important to have two lefty specialists because then you don’t get caught “saving” your guy while letting a game get away. Jennings (.226 vs. lefties) and Cedeno (.193) are two strong options.

The Matchup Righties: Joakim Soria, Taylor Williams and Freddy Peralta

Soria (.195), Williams (.209) and Peralta (.111) all stifle righties, but in different ways. Soria is tough on righties who can’t handle a change of speeds because in addition to his pinpoint fastball he throws slow (changeup at 87), slower (slider at 79) and slowest (curveball at 70). Williams is your prototypical two-pitch power reliever (fastball at 96 and a slider thrown on the same plane). Peralta is converted starter with command issues with fastball/curveball combo that is death to righties. Righthanders hit .111/.209/.396 off Peralta—only A’s closer Blake Treinin was tougher on righties—while managing just 2-for-25 against his 150 curveballs.

The Early Closer: Corey Knebel

The former closer is pitching again like a closer, just not in the ninth inning. When he throws his curve over for a strike, he’s unhittable. Since he came back from a minor league demotion, Knebel has not allowed a run (15 1/3 innings) and struck out 32 of 54 batters faced (59%).

The Strikeout Machine: Josh Hader

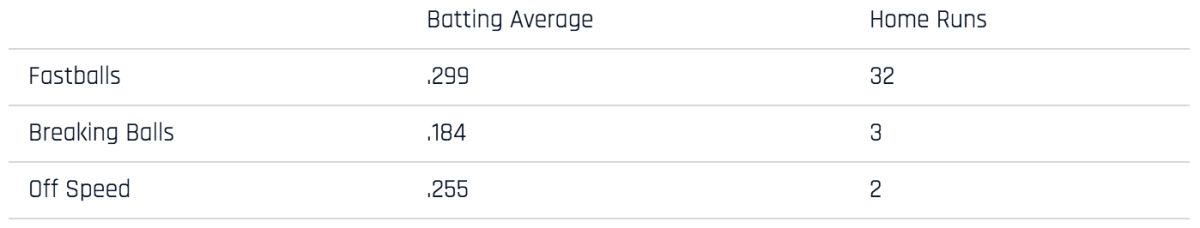

Hader has an electric fastball. Batters hit .133 against it. But when he throws it low in the zone, as has happened lately, he gets hit:

Batters vs. Hader Fastball

The Late Closer: Jeremy Jeffress

He’s a rare three-pitch closer, including the rare endgame split: fastball (96-97), tight curveball (low 80s) and split (91). The split makes him especially tough to hit. Jeffress has thrown 191 of them this year and not allowed an extra-base hit.

Smartly, Stearns has built a bullpen without duplication. There is a mix of left and right and varied arm angles and stuff. Total cost to Milwaukee for those eight relievers: $11.4–or $1.6 million less than what the Yankees are paying David Robertson.

Counsell doesn’t like to identify his relievers as having “roles.” He’s gone all post-modern bullpenning by simply calling them “out-getters.” He goes to certain relievers when score and batter dictate, not inning. Hader, for instance, is not “an eighth-inning guy.” He has pitched in every inning from the fourth through the 10th.

As well as Counsell deployed his bullpen in the regular season, he should be even more advantaged in the playoffs because of so many off days. Last year, for instance, the Astros had 13 off days around 18 postseason games–that’s a half-season’s worth of off days in one month, which allows Counsell to use his relievers even more.

So when you watch the postseason, rest assured that Koufax, Drysdale and Osteen are not pitching. This is the game today: a proliferation of relievers with powerful stuff, and managers armed with specific data on how best to deploy them. Yes, on occasion a manager will get burned because a reliever gives up a lead. No plan is foolproof. But this formula works.

We just finished a season in which it was harder to get a hit than at any time since the DH was added in 1973. When pitching is the hardest to hit in 47 seasons we have all the proof we need that trimming starters’ work and giving it to relievers is a successful strategy, if not exactly a welcome aesthetic one. And this October, nobody can play this game better than Milwaukee.

RANK 'EM: THE WORLD SERIES MATCHUPS WE WANT TO SEE

By Jon Tayler

Ten teams will enter the 2018 postseason, but only two will be left standing for the World Series. But which teams would make for the best pairing in the Fall Classic? Let’s rank all 25 potential matchups, from worst to best, and please feel free to let me know via Twitter or email how bad and stupid my choices are.

25. A’s-Braves

It’s not an old or heated rivalry, and marquee names are lacking on either side. In terms of viewers, this is Rob Manfred’s worst nightmare: Your average NFL preseason game might outdo the TV ratings for this.

24. A’s-Brewers

Two similar teams—tons of power, awesome bullpens, pitching staffs that appear to have been assembled drunkenly—that disappointingly won’t draw a lick of mainstream interest. But just imagine Joe Buck yelling “Wade Miley! Edwin Jackson! It’s Game 1 of the World Series!” on the broadcast and see if you can stifle your giggles.

23. Indians-Braves

It’s the World Series we should’ve gotten in 1997, if it weren’t for those meddling Marlins. (Fun fact: Ronald Acuña was born two months after the end of the ’97 World Series! Every day is one step closer to death.) I want an exhibition game during it between the ’97 Braves and Indians, just to watch 46-year-old Manny Ramirez against 52-year-old Greg Maddux.

T18. Indians-Rockies

T18. A’s-Rockies

T18. Astros-Rockies

T18. Red Sox-Rockies

T18. Yankees-Rockies

I’m grouping these together under the principle that no World Series featuring games in the bouncy house that is Coors Field can be ranked last. A Yankees-Rockies Fall Classic would see Aaron Judge or Giancarlo Stanton hit .745 with 12 homers, and I’m pretty sure the Astros would score 17 runs a game in Colorado. That said: The constant winking marijuana references from the Fox booth during an A’s-Rockies tilt would get tired fast.

T16. Red Sox-Braves

T16. Astros-Braves

Both Boston and Houston have won in recent years, taking some of the charge out of these pairings, and there’s no ancient rivalry here (unless Atlanta wants to dig up some members of the old Boston Braves, though they may have to do that literally; I think all of those players are dead). Still, these teams can hit and are loaded with young stars.

15. Yankees-Braves

Let’s revisit the 1996 World Series! Like Indians-Braves, this one is all about history, though the parade of great young talent—Ronald Acuña, Ozzie Albies, Mike Foltynewicz, Aaron Judge, Gleyber Torres, Miguel Andujar—makes this a great showcase for the future of the game, too.

With David Wright’s Sendoff, Mets Bid Farewell to a Star and an Era

14. A’s-Cubs

Something about this pairing just makes me smile. You’d have lots of homers and offense, for sure, and Oakland’s terrific bullpen could easily steal some games late. Plus, you’d get to watch the sublime defensive stylings of Javy Baez and Matt Chapman.

13. Indians-Cubs

A 2016 rematch that’s fun on paper, though neither team looks as good as it did two years ago. This matchup would suffer from comparison to that classic title bout, but there’s still a lot of starpower on each side, and a chance at sweet, sweet October revenge for Cleveland.

T11. Red Sox-Brewers

T11. Yankees-Brewers

The AL East teams are interchangeable, given that both have awe-inspiring lineups. Boston has the better rotation, New York the better bullpen—and the Brewers can match either offensively. There’d be a lot of runs in these matchups, plus a potential MVP showdown in Mookie Betts versus Christian Yelich.

10. Astros-Dodgers

The 2017 rematch loses points for happening so soon, and for the Dodgers looking like a fuzzy VHS copy of last year’s squad. But the possibility of getting that incredible Game 5 high once again is enough for me root for this matchup.

9. Indians-Brewers

Another series that won’t move the needle ratings-wise, but you have the allure of both franchises competing for a long-elusive World Series. For the Indians, it’s been 70 years since they won a championship. For the Brewers, it’s been their whole existence (though older Milwaukee folks have the Braves’ win in 1957). “Title droughts that span literal generations” makes this one extra compelling.

8. Astros-Cubs

The Process Bowl! Eagerly listen to the broadcast wax rhapsodic about the virtues of intentionally being really bad and losing a lot of games so that, an unspecified number of years later, you can be good again (assuming lots of things go exactly your way). This would be one hell of a clash between the two would-be dynasties of the game, though.

How Many Teams Have Won the World Series After Having the Season's Best Record?

7. Indians-Dodgers

The Runner-Up Bowl! The beauty of this is that two long title droughts enter, but only one will remain by the end. The drama of that alone makes this a winner, as does the presence of Francisco Lindor, Jose Ramirez, Manny Machado, Yasiel Puig—and a potential Corey Kluber-Clayton Kershaw duel. Yes please.

6. Red Sox-Dodgers

History, superstars on super-teams, beatwriters having to pack for both Boston and Los Angeles in the same week in late October—this one has it all. Chris Sale versus Clayton Kershaw would be spectacular. Mookie Betts and Manny Machado in the spotlight would be wonderful. J.D. Martinez and Justin Turner as the Bad Hitters Reborn All-Stars would be fun. This would be a delightful seven-game series.

5. Astros-Brewers

I love this matchup, and not just because both teams rake. Houston and Milwaukee each have terrific bullpens, too, and this never-say-die Brewers squad would be a fitting challenger to the Astros’ throne. This may have the look of a bland small-market combo with no history to speak of, but the product on the field says otherwise.

4. A’s-Dodgers

A 1988 redux, as both teams would try to end three-decade title-less streaks. And the storyline is practically Hollywood: the upstart, underdog A’s on their pipsqueak payroll against the mighty Dodgers, who could buy that entire team with a fraction of their operating budget. It’d be (Khris) David against Goliath.

3. Yankees-Dodgers

The most Dad matchup of all the World Series possibilities, this would be a long, slow settle into a recliner for Story Time about these ancient rivals and their clashes in the 1950s, when the game was perfect and nothing else mattered. Fox would have to broadcast this in black and white for nostalgia purposes. But these teams are excellent in the present, too, so this is more than just “Ken Burns Presents: The World Series.”

T1. Red Sox-Cubs

T1. Yankees-Cubs

When Rob Manfred goes to sleep at night—for exactly two hours and 25 minutes, his ideal length of time for a baseball game—these are the matchups he sees in his dreams in between visions of infields without defensive shifts. These would be ratings and cash bonanzas for the league and Fox, but for the fans, they’d also be stupendous combos of power, youth, history and plain old fun.

JUST ANOTHER MONDAY IN SEPTEMBER

By Tom Verducci

It’s only a snapshot, but I wish I could say it’s an anomaly. Two decades after then Rangers GM Doug Melvin officially pushed to control the issues created by expanded September rosters, Major League Baseball and the Players Association still have done nothing about what is becoming a more inferior product in the final month of the regular season.

The runaway usage of bullpens and the declining amount of balls put in play have exacerbated the problem. There were 12 games played last Monday, Sept. 24. Here is what happened, thanks to managers having use of 40-man rosters:

• Three teams, all of them with winning records, used an “opener” and “bullpenned” the entire game: the Yankees, Rays and Brewers.

• Starting pitchers averaged 4 2/3 innings–less than the minimum to qualify for a win.

• The 12 games featured 125 pitchers, or 10.4 pitchers per game.

• Teams used almost as many pitchers in one night (without a full schedule) as they did to play the entire 1904 season (129), and more than half as many as they used to cover the entire 1960 season (238).

• Thirteen pitchers faced only one batter.

• Batters hit .238, essentially mimicking the worst offensive season in baseball history, 1968 (.237).

• The average four-seam fastball was 93.5 mph.

• There were 564 balls in play, or one every four minutes.

• There were 3,551 pitches, which means managers changed pitchers on average every 28 pitches, and 84% of pitches were not put in play.

• The games averaged 26,834 fans—6.3% below the overall 2018 average, 10.3% below 2017, and 17% below 10 years ago.

• The average time of game was three hours, seven minutes.

ROUNDTABLE: DO YOU ENVISION THE ONE-GAME WILD-CARD FORMAT STAYING PUT? HOW COULD IT BE IMPROVED?

Emma Baccellieri: I think that baseball will have to reckon with this question in the next decade, as the prospect of expansion is repeatedly raised; a different format will almost certainly come along with a hypothetical 32-team MLB. As the league is now, though? I think that the current system works as well as anything. A best-of-three would still keep much of the random feel of a single game, and it would likely mess with scheduling and players’ rest. Backpedaling to just one wild card seems like it would be impossible, after fans have gotten to experience the excitement of two facing off in a must-win contest. The current format isn’t perfect, but at the very least, it keeps things interesting.

Gabriel Baumgaertner: I like the format as it is, but I do think that the two teams with the worst records—division champions be damned—should be the teams playing in the one-game playoff.

Connor Grossman: I'm an advocate for the one-game, do-or-die gauntlet baseball fans are immediately treated to at the start of the postseason. For the sake of ideas, though, here's something to swish around: What about tweaking the wild-card format to a two-game series? The second wild-card team must beat the first wild-card team twice on the road to advance in the postseason. The advantage would sit clearly with the first wild-card team. Maybe this two-game series would only be "activated" if the first wild-card team finished X games (let's say eight) ahead of the second wild card. That way you offer elite teams a bit more protection from the one-game fluke. That being said, the current system is just fine. Keep swishing.

Mike Scioscia Not Returning to Angels After 19 Seasons as Manager

Jon Tayler: Yes, the wild-card format will likely stay, if only because it’s provided a lot of drama each year and because I’m not sure how you would do this any better. Maybe a three-game wild-card series to make it somewhat more fair? I don’t know if that’s a better solution, but it’s the only one I see—and I don’t think I’d want it, anyway. One game is cruel and agonizing, but it’s also high theater.

Tom Verducci: As long as we have 30 teams (rather than two 16-team leagues) the one-game wild card format will stay exactly as is. Baseball and the rest of us want no part of adding to the inventory of non-decisive postseason games, so forget the idea of a best-of-three format. Kicking off the postseason with (at least) two win-or-go-home games is the right way to go, and ratings prove it.

INSIDE THE TWO CRUCIAL MATCHUPS IN ASTROS-INDIANS

By Tom Verducci

Here are the key matchups in the Houston-Cleveland series: Indians second baseman Jose Ramirez, the best slugger against fastballs in baseball, hitting against Astros pitchers Justin Verlander and Gerrit Cole, two of the best four-seam fastball pitchers in baseball.

Ramirez slugs .719 against fastballs, the highest mark in baseball. Why? He has such a quick bat and loves to hit the ball out front, so he does almost all of his damage to the pull field–even on fastballs away.

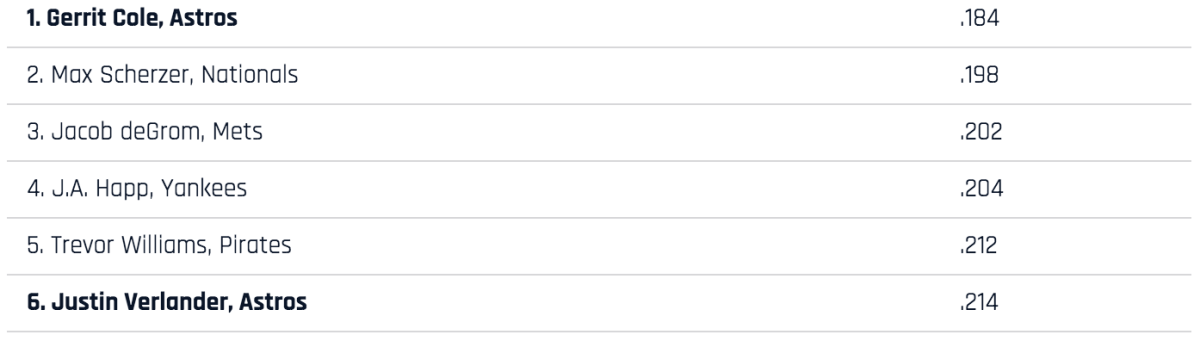

As for Verlander and Cole, check out where their fastballs rank:

Lowest Batting Average vs. Four-Seam Fastballs (Min. 250 results)

So what does history tell us about these power vs. power matchups?

Ramirez vs. Cole: He was 1-for-3 May 27, the only time he faced him. The hit was … you guessed it … a pulled home run on a Cole fastball away. Cole threw 165 four-seamers away this year to lefties, and Ramirez was the only one to pull it for a home run.

Ramirez vs. Verlander: How about this career slash line in 32 plate appearances: .407/.500/.741. Ramirez has the highest OPS (1.241) of any batter who has faced Verlander at least 30 times.

Cole and Verlander will throw Ramirez fastballs because they are fastball pitchers, but they should be very strategic fastballs that set up their secondary stuff. These numbers by Ramirez clearly tell you how to approach him:

Jose Ramirez vs. Pitch Type, 2018

HOW PITCHERS SHOULD ATTACK AARON JUDGE IN OCTOBER

By Tom Verducci

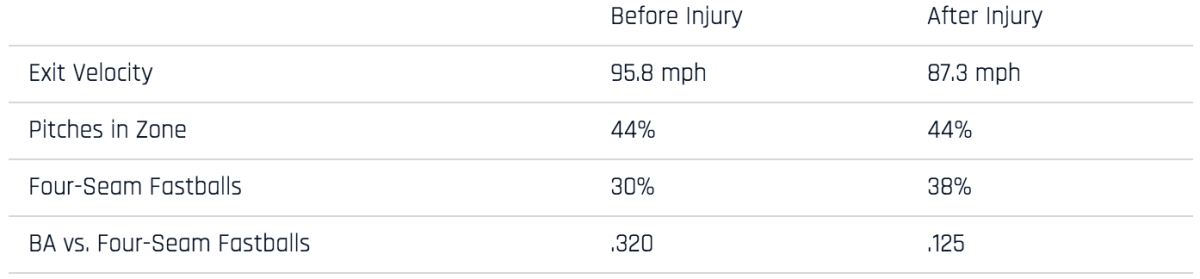

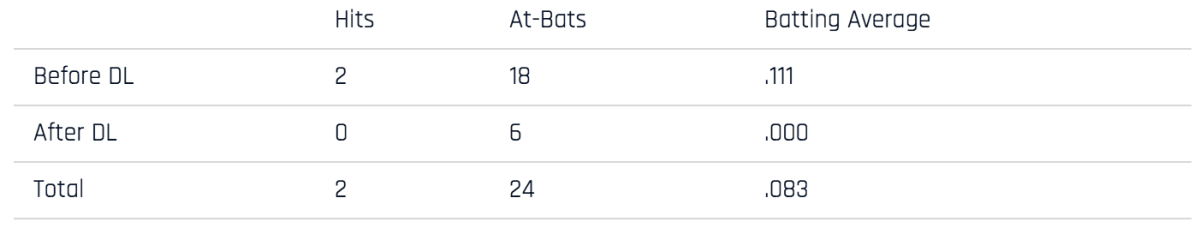

New York Yankees outfielder Aaron Judge isn’t nearly the same hitter he was before his wrist injury, but pitchers still fear him. Though Judge is not hitting the ball as well or as hard, pitchers still throw him few pitches in the zone:

Aaron Judge Before and After DL

Oakland must challenge him with high fastballs:

Judge vs. Elevated 4-Seam Fastballs

LEAVE THE WILD-CARD GAME ALONE

By Emma Baccellieri

Every year now there is some griping about the playoff format. This season, it began early—June, and it continued throughout the summer. Even then, far before the postseason’s picture came into focus, some people found it easy to see something unfair, or close to it. The Yankees could win 100-plus games and still fail to win the AL East, meaning that their season might come down to a one-game playoff against a far weaker team. That didn’t happen; at least, not exactly. The Yankees did win 100 games while failing to win their division, but they’ll be facing a wild-card opponent who’s just about equally qualified, the 97-win Oakland A’s. Still, it seems fitting now to wonder: Is the current one-game wild-card playoff, now in its seventh season, fair?

The 2018 Yankees are not the first team to raise this question of fairness, of course. The 2015 Pirates had the second-highest win total in all of baseball and still were subjected to, and lost, the one-game playoff. That would seem to be more patently unfair than anything that could have happened this year. Is MLB’s goal here to be fair, though? The question might seem obvious to the point of stupidity. But one could argue that an entertaining postseason might be a higher priority than a perfectly fair one, and that those two aren’t necessarily the same thing.

As Adam Wainwright Faces an Uncertain Future, One SI Writer Relishes Chance to See a Final Curveball

The one-game playoff between the two wild-card teams gives a high-stakes jolt to the beginning of the postseason. It’s fun, because it’s unlike just about any other regular feature in baseball. (Professional baseball, at least—college baseball has its own version, which is just as much of a blast.) But much of the excitement comes from the fact that anything can happen here, which is precisely what can be said to make it unfair. The winner of a single game isn’t random, but it might as well be. The specter of injustice follows the winning team into the next round, too, as surviving the wild-card game typically means burning its best starting pitcher and a key reliever or two before the divisional series has even started.

If you believe that a team’s playoff destiny should be directly tied to its regular season record, then it’s all terribly unfair—but if perfect fairness was the goal, there wouldn’t be any postseason, only a champion awarded based on win total. The current system improves on the previous one by opening the door to one more club and adding a burst of intensity right at the start of October. There isn’t much to be gained by making the single game into a best-of-three, as has been suggested, which would only make it slightly more likely that the better team would actually win and make it much more likely that they’d suffer from fatigue and a depleted pitching staff in the next round. And if the idea of the wild card is just that offensive? Well, it provides extra incentive for a team to win its division, which is almost certainly a good thing, encouraging competition throughout the year. In other words, if you don’t like it, just win, baby—and everyone else can sit back and enjoy the show.

SETTING PROP BETS FOR THE 2018 POSTSEASON

By Gabriel Baumgaertner

Will the Dodgers ever field the same lineup twice during their playoff run?

Yes (-110)

No (-110)

Will the wild-card game at Yankee Stadium finish in under four hours?

Yes (-135)

No (+150)

Will Corey Kluber fist-pump or shout if he makes a big play at any point in the playoffs?

Yes (+150)

No (-200)

How many times will you hear that Clayton Kershaw went to high school with Matthew Stafford?

O6 (-115)

U6 (-105)

How many Christian Yelich/Pete Davidson side-by-side graphics will appear?

O5 (-110)

U5 (-110)

David Wright Was Everything the Mets Could Have Hoped for

How often will Javy Baez be referred to as “the best tagging infielder ever”?

O8 (-135)

U8 (+125)

How many times will a color commentator cite the effectiveness 2014 and 2015 Kansas City Royals after a bullpen falters in their game?

O5 (+150)

U5 (-175)

Will Joe Maddon’s eccentric bullpen usage end up costing the Cubs a playoff game?

Yes (-125)

No (+115)

Will Charlie Blackmon’s beard suddenly begin housing eggs and baby chicks?

Yes (-110)

No (-110)

How many playoff home runs will Ronald Acuña have?

O1 (-150)

U1 (+175)

FROM THE VAULT: AN UNBREAKABLE BOND THROUGH BASEBALL

By Connor Grossman

When it comes to classic October moments, you'd be hard pressed to top Bobby Thompson's "Shot Heard 'Round the World" on October 3, 1951. His homer secured the National League pennant for the New York Giants, which is better summed up by Russ Hodges's legendary call: "There's a long drive ... it's gonna be, I believe ... the Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!" Thompson belted a curveball from Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Ralph Branca, and the two have been inextricably tied ever since.

Fourty years after the epic duel, SI's Ron Fimrite explored the lasting relationship between Thompson and Branca. Spoiler: there is no bitter ending to this classic Giants-Dodgers tale. Enjoy the excerpt to Fimrite's story below and find the entire piece here.

Branca had dinner that night at Daube's Steak House in the Bronx with his fiancèe, Ann, and the Rube Walkers. They were met by Ann's cousin Father Frank (Pat) Rowley, a priest at Fordham University. Branca recalls, "I said to Father Rowley, 'Pat, why me? Will you tell me, why me?' And Pat said, 'Ralph, God chose you because He knows your faith is strong enough to bear this cross.' That struck home. It was my salvation. I realized that I had done the best I could. The guy just hit a home run. He was better than I was this day. Life goes on. You don't go through it undefeated.... But I don't care what anybody says, that's the most famous home run of them all."

Thomson had dinner afterward with his family at the Tavern on the Green in Staten Island. He was reveling in his newfound glory when, at about 11 o'clock, it occurred to him that he was forgetting something important. "Hey, everybody," he shouted from atop a chair, "I gotta play the Yankees tomorrow."