Exploring Baseball's Cultural Heritage in 100 Photos

The following is excerpted from THE STORY OF BASEBALL IN 100 PHOTOGRAPHS, edited by Kostya Kennedy, written by Bill Syken. Copyright © 2018 Time Inc. Books, a division of Meredith Corporation. Published by Liberty Street, an imprint of Time Inc. Books.

The first celebrated photographs taken in the United States—among them portraits of former President John Quincy Adams and President James Polk—were shot in the 1840s, which was right about the time that the first organized baseball games, staged in front of audiences and guided by essentially the same rules that guide the game today, were being played. In the years and decades that followed, both photography and baseball blossomed in popularity. Sports Illustrated’s The Story of Baseball in 100 Photographs explores baseball’s cultural heritage and its path to becoming the country’s national pastime through evocative, extraordinary photos, from the days of Babe Ruth to the thrilling championships of today.

Beginning of the world

Huntington Avenue Grounds, Boston, October 1, 1903

The first world series was more a peace offering than a battle for supremacy. In 1901 and ’02 the National League and the American League had been locked in pitched battle. The NL, formed in 1876, was baseball’s top circuit, but in 1901 the American League declared major league ambitions, placing franchises in NL cities and engaging in bidding wars for top players. In ’03 the leagues reached a truce and commemorated it with the creation of the World Series. Postseason play between leagues was not unprecedented. There had been such games in the 1880s, and in 1902, the NL champ Pittsburgh Pirates played an exhibition series against an AL All-Star team. This first World Series was a best-of-nine affair, in which the Boston Americans (renamed the Red Sox in ’08) beat the Pirates five games to three. Boston’s Cy Young threw the first pitch in the inaugural World Series before a crowd of more than 16,000, about three times the average of what Boston drew at home. Young lost that game but won two others while Pittsburgh’s Honus Wagner became the first star to lay a postseason egg, batting .222 after leading both leagues with a .355 average. In ’04 there was no World Series at all—New York Giants manager John McGraw said his NL champs didn’t need to prove themselves against the upstart league—but it resumed in ’05, a tectonic step in the development of major league baseball.

The Babe

Sportsman’s Park, St. Louis, October 6, 1926

Babe Ruth didn’t break a mold so much as create one. He began his career at the end of a Dead Ball era, when managers emphasized baserunning and defense, and the sacrifice bunt was a significant offensive weapon. But rules changes—including the banning of the spitball in 1920 and enforcement of regulations against other doctored pitches—set the stage for a new kind of offensive star, and Ruth showed baseball the power of swinging for the fences.

He began his career in 1914 as a mighty lefthanded pitcher with the Red Sox, going 67–34 with a 2.07 ERA over his first four seasons. But Ruth soon saw that he would be better off concentrating his energies at the plate. In ’19 he hit 29 home runs, then a single-season record. That offseason Boston sold his contract to the Yankees for $100,000. In the first year in his new home Ruth hit an astonishing 54 home runs, more than the totals of every other team in the league but one. The original “Ruthian” blasts elevated this former Baltimore street urchin with the moon-shaped face into the biggest star sports had ever known—given to feats such as hitting three home runs in a single World Series game, which he is in the process of doing in the photo at right. Ruth was a hot-dog eating, whiskey-drinking, showgirl-dating, orphan-aiding, shot-calling, management-sassing, big-money-earning Sultan of Swat. And in the years following the 1919 Black Sox scandal, when many baseball fans were disillusioned or disenchanted, Ruth was a player to enchant and to believe in. He set home run records for a single season (60 in ’27) and a career (714) that stood for decades, and to this day he holds the career mark in slugging percentage and OPS. Ruth was the best.

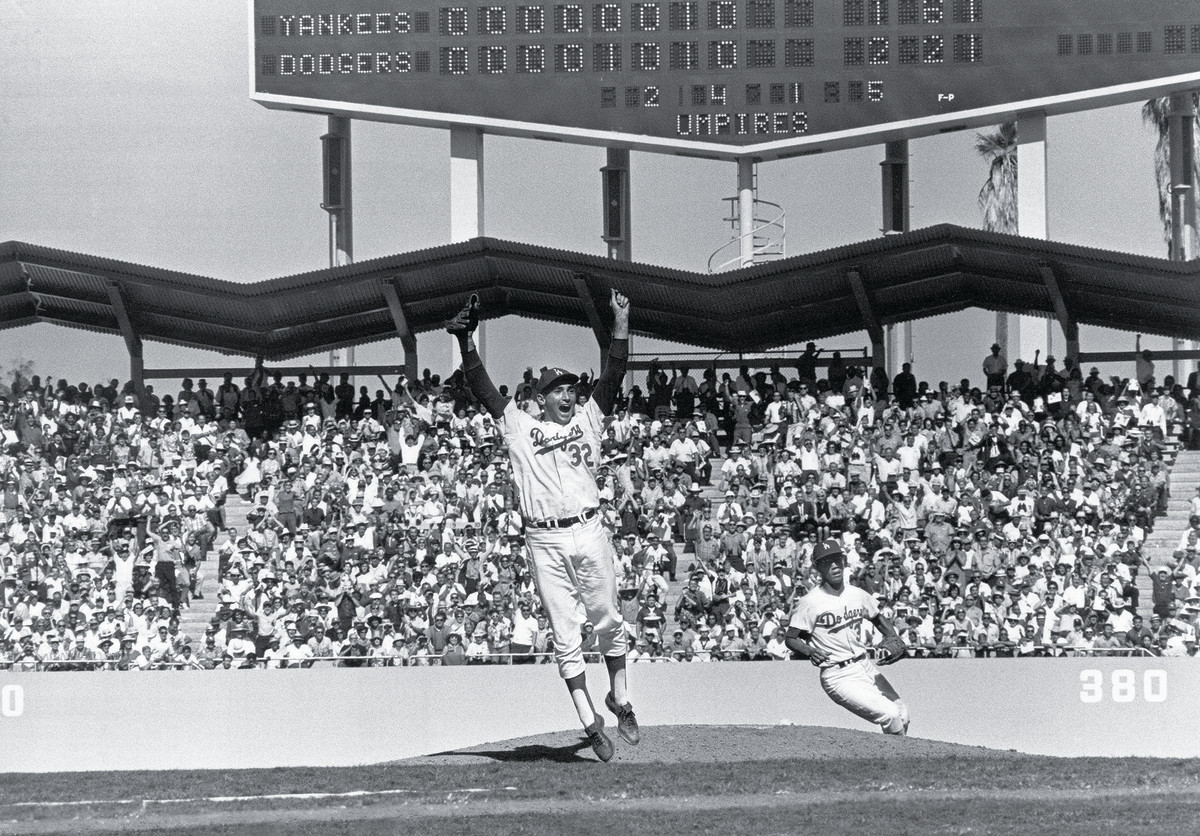

Pure Greatness

Dodger Stadium, Los Angeles, October 6, 1963

Sandy Koufax had been merely good through the first seven seasons of his career, but beginning in 1962 he went on one of the greatest runs any pitcher has known. Suddenly, having tweaked the delivery on his fastball, the Dodgers lefty was all but unhittable. From ’62 to ’66 he won three Cy Young awards and led the league in ERA each year. He went 111–34 in that time, pitching four no-hitters (one a perfect game) before retiring at age 30 because of arthritis in his pitching elbow. In the ’63 World Series against the Yankees, Koufax’s mastery was on full display. He won two starts against Whitey Ford, including a 2–1 win in Game 4 that completed the Series sweep (right). In the ’65 Series Koufax again won two games (both shutouts) and took a loss in Game 2, when he allowed a single run. But his most remembered World Series performance may be the game in the ’65 Series that he didn’t pitch. Koufax informed the Dodgers that he would not be available for Game 1 because it fell on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, which is marked by fasting, atonement and rest. At the time little fuss was made over Koufax’s choice. He had missed regular-season games for religious reasons before and the Dodgers had Don Drysdale, a nine-time All-Star, to start Game 1. (Drysdale was shelled, after which he reportedly joked to manager Walter Alston, “I bet you wish I were Jewish too.”) But Koufax’s stand became a celebrated moment. He showed that you could be a ballplayer and an American and a Jew, and do it all the right way.

Move Over, Babe

Atlanta Stadium, Atlanta, April 8, 1974

As a teenager in Alabama in 1948, Hank Aaron skipped school to hear his hero Jackie Robinson speak at a drugstore and came away inspired. Aaron began his pro career with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro leagues, before coming to the Braves as a minor leaguer in ’52. What he did after reaching the majors two years later was establish himself as the most consistently great slugger in baseball history. Hammerin’ Hank never hit more than 47 home runs in a season, but he hit 38 or more 11 times and he climbed the all-time list; at the end of ’73, his total of 713 was one behind Babe Ruth’s career mark. Some fans wrote racist hate mail to Aaron who saved the letters as a reminder of what he faced, even as he kept on hammerin’. Ruth’s record had loomed for nearly 40 years, and in the first series of ’74, at Cincinnati, Aaron tied it. Then when the Braves came home to play the Dodgers, Aaron swung at an Al Downing fastball and sent it over the fence in left center. He circled the bases, maintaining his cool as two fans came onto field and ran a few steps alongside him between second and third—and when he reached home, he was met by ecstatic teammates and his parents.

“What a marvelous moment for the country and the world,” said Vin Scully, the Dodgers’ great announcer. “A black man is getting a standing ovation in the deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.” Aaron hugged his mother and shook his father’s hand. And when he came to the microphone on the field to address the fans, his first words were about how happy he was that the chase was over.

Slow Ride

Shea Stadium, Queens, N.Y., August 26, 1983

It is often the nature of technology that first we find out if we are capable of creating something, and then we wonder whether we need it. It was like that with the baseball cart. The early adopters, if you will, were the Indians in 1950 and the White Sox in ’51. These versions were just cars—though the comedy potential was tapped early when Chicago provided the visiting team with a hearse to transport its relievers. The Milwaukee Braves tried a chauffered Harley-Davidson scooter with the pitcher riding on a sidecar. The first golf cart appeared in ’63, with the L.A. Angels. But like so much new technology, it didn’t really go viral until the design was perfected, and that happened in ’67, when the Mets introduced their take on the cart. That look—a baseball body topped by a team cap—became the standard. By the ’70s, just about every team had one, and they became as much a visual signature of that decade as wide collars and disco balls. Maybe the Mariners took it too far. Seattle intended to haul its relievers out to the mound riding a miniature fire boat (it looked like a tugboat). Reliever Jesse Orosco (at right) would wind up coming in from the bullpen more than any pitcher ever, and, pitching from 1979 to 2003, he bridged a cultural divide. What was cool became uncool: Pitchers started running in from the bullpen under their own power. Maybe a pro athlete being dropped off at the mound like a kindergartner being taken to school wasn’t the greatest look after all. The carts disappeared—when the Diamondbacks brought one back in ’18, few pitchers used it—but the charms of the object remain. In ’15 the original Mets cart came up for auction at Sotheby’s, and while the estimate was that it might fetch $20,000, it sold for $112,500. Beauty is never obsolete.

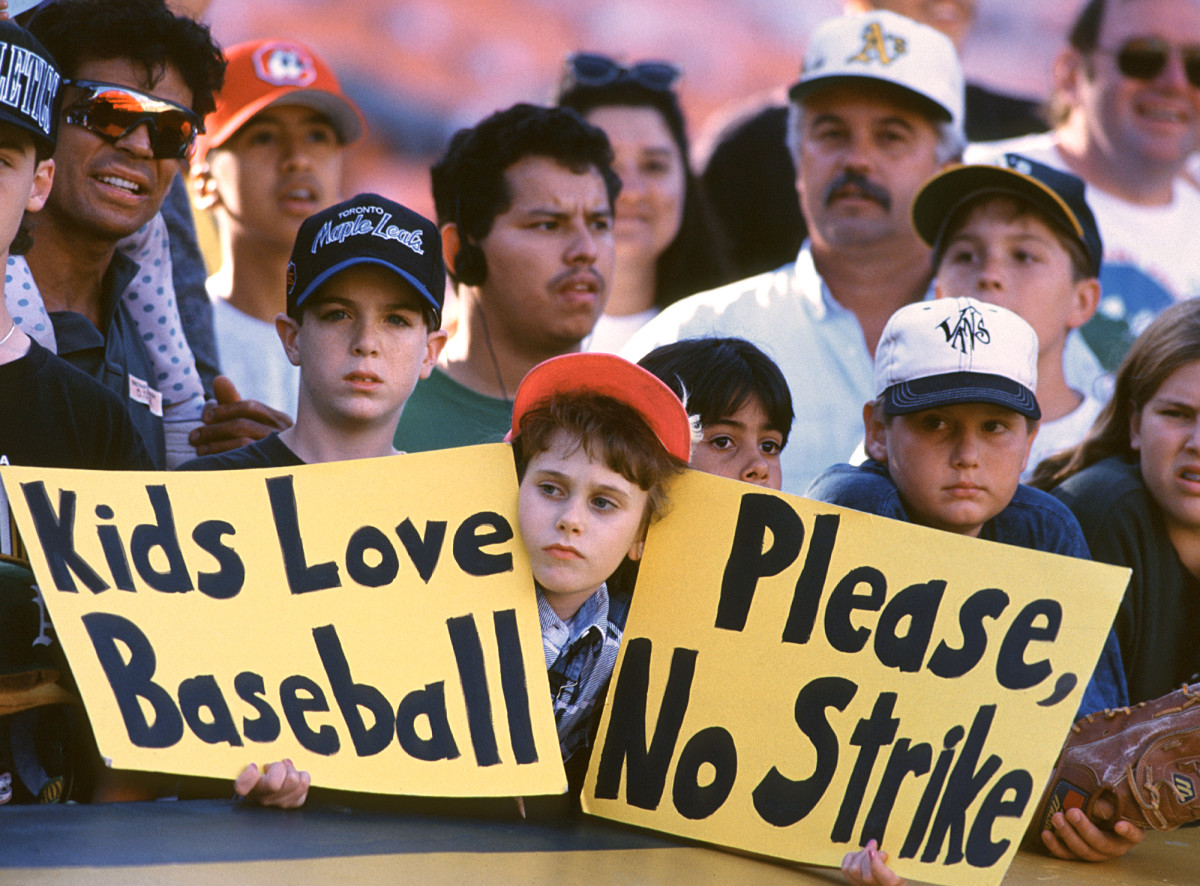

Foresaking the Faithful

Oakland Coliseum, Oakland, August 11, 1994

The promise of every sports season is that it will end in the crowning of a champion. That promise was broken, for the first time in any sport, with the baseball strike of 1994. Baseball had seen seven previous work stoppages, including a nasty one in ’81 that cut out the middle of the season and resulted in the oddity of sending first-half and second-half champs to the playoffs (while the Cincinnati Reds, owner of the best overall record in the National League, stayed home because they hadn’t won their division in either half). But the ’94 strike was worse. The owners wanted to impose a salary cap, and the union, led by Donald Fehr, wouldn’t go for it. So the games stopped on Aug. 12—the day after these fans pleaded for mercy at a Mariners-A’s game—and didn’t resume. No playoffs, no World Series. Lost in the work stoppage were dramas such as Tony Gwynn’s run at .400 (he was at .394 when the players struck) and Matt Williams’s chance to surpass Roger Maris’s single-season home run mark. (Williams had 43 before the strike wiped out his Giants’ final 47 games.) The ’94 strike may have been most painful to fans in Montreal. The Expos had baseball’s best record at 74–40 when the curtain went down. Imagine the frustration of rooting for a team that had never won a postseason series, and the year they’re really good, baseball cancels its playoffs. Fans around the league were so disgusted that in 1995 (a strike-shortened, 144-game schedule began on April 25) average attendance was down 20%. The one positive of the strike was that it was such a disaster both sides may have learned something: Baseball hasn’t had a work stoppage since.

Phans Delight

Veterans Stadium, Philadelphia, July 2, 1995

The resemblance between the Phillie Phanatic and a Muppet is not a coincidence: The mascot was created in Jim Henson’s puppet factory. And like Kermit the Frog and Fozzie Bear, the Phanatic, even in his mascot’s silence, has been entertaining families for generations. Costumed mascots have enlivened baseball since Mr. Met arrived in 1964, and he helped amuse fans through long and losing seasons. By now all but three big league teams have a mascot, and Mr. Met has a wife (above, the couple is hosting friends at the 2013 All-Star Game). The Phanatic, introduced in ’78, is one of the most popular in the game, and the extent to which he took off in Philadelphia was unexpected. At the time of his creation the Phillies were offered the copyright to the character for an extra $1,300 and turned it down. A few years later the Phanatic was a bona fide star and the team bought the copyright—for $250,000. For 16 seasons the Phanatic was played by Dave Raymond, who was tapped for the job while a student intern and who possessed a gift for nonverbal communication he attributed to being raised by a deaf mother. The Phanatic became the best kind of stadium hero—one who never gets injured, goes into a slump or leaves in free agency.

The Phanatic does his best work in dugout dances, hexing visiting pitchers and generally taunting members of the opposing team, such as the fallen Atlanta Brave at left. His craziest day occurred during the summer of 1988 when he was clowning with a blow-up doll dressed in a Tommy Lasorda jersey (with overstuffed belly). The Dodgers manager came out of the dugout and, with no humor and little restraint, hit the Phanatic with the doll, nearly knocking off the mascot’s head. Mascots, now ubiquitous across sports, were at the forefront of changing times at the ballpark—as game action became augmented with kiss cams, theme nights and T-shirt cannons. The players are the stars of the Show, but mascots are the ringleaders of the circus.

Tainted Time

Capitol Hill, Washington, D.C., March 17, 2005

In 1998 Sports Illustrated named Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa its Sportsmen of the Year, and a headline above the story declared “Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa treated the nation to a home run race that was as refreshing as a day at the beach.” Soon after, though, fans were feeling burned. In ’98 McGwire and Sosa not only chased Roger Maris’s single-season home run mark but caught it and beat it into submission with their massive biceps. In real time the chase played as baseball’s most entertaining show in ages. But the memory has been robbed of its joy. It now calls to mind a time when accusations against baseball’s heroes came in waves and turned the sports pages into a police blotter. McGwire was implicated in the use of performance enhancing drugs by ex-teammate Jose Canseco, himself an admitted user. In 2005 Canseco (far left), Sosa (center) and McGwire (second from near left) were called before a congressional committee to testify about steroid use. To McGwire’s left was Rafael Palmeiro, who hit 569 career home runs and angrily declared to the committee, “I have never used steroids, period!” before being suspended later that season after testing positive for stanozolol. Sosa, reported to have tested positive for PEDs in ’03, has steadily denied such charges. McGwire issued many denials before finally admitting, in ’10, to steroid use. At the ’05 congressional hearings, wanting to avoid perjury charges, McGwire only said, “I’m not here to talk about the past.” For many from that era, the past remains an awkward subject.

The Song Before the Game

Camden Yards, Baltimore, April 4, 2005

Baseball is an American game—as American as apple pie and Chevrolet, according to the calculus of a 1970s car advertisement. The game is also where “The Star-Spangled Banner” and sports first became intertwined. During the Cubs–Red Sox World Series of 1918, as the United States was in its second year of fighting in World War I, a live military band performed the song during the seventh-inning stretch at Chicago’s Comiskey Park (which the Cubs had rented to accommodate the larger crowd), and the audience began to sing the words. More and more voices joined in and the final words “the home of the brave” were followed by thunderous applause. A New York Times report called the performance “the high point of the day’s enthusiasm” and the music continued when the Series moved to Boston. From then on live bands regularly performed the anthem at World Series games and on special occasions. The anthem graduated to an every-day, pregame event during World War II, by which time public address systems had been improved to the point that a recording could be broadcast throughout the stadium. The ballplayers removed their caps, and the fans put their hands on their hearts. The patriotic displays escalated after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, when Major League Baseball required that teams also play “God Bless America” during the seventh-inning stretch for the rest of the year. Now teams tend to reserve “God Bless America” for Sundays and holidays. But for every game, such as this Orioles Opening Day, “The Star-Spangled Banner” tradition, and our flag, is still there.

The Weight is Lifted

Progressive Field, Cleveland, November 2, 2016

After winning back-to-back World Series in 1907 and ’08, the Cubs lost in the Series in ’10 but surely figured, How far off could the next title be? The Cubs did reach the World Series again—six times, up through 1945—but they never won one and the wait, after a certain point, became the stuff of gallows humor, a catalog of cursed moments and some near misses, a reason to shrug in the City with Broad Shoulders. The Red Sox had ended their own 86-year drought in 2004. When would Chicago’s turn come?

In Game 7 of the ’16 World Series against Cleveland, the Cubs held a three-run lead with two outs in the eighth inning when the Indians rallied to tie. But this time, when it all seemed to be going wrong, Chicago benefited from divine intervention in the form of a 17-minute rain delay that gave the reeling Cubs an opportunity to regroup. They did, scoring two runs in the 10th, going ahead on Ben Zobrist’s RBI double. In the bottom of the inning, third baseman Kris Bryant fielded a two-out ground ball and threw to Anthony Rizzo at first, and Chicago’s 108-year wait, the longest interim between titles known to man, was over. “Right now,” Dave Martinez, a Cubs bench coach and former player, told SI then, “I think about the parents and the grandparents—all the people who waited for this day and the many of them who never lived to see it.” The victory parade was attended by five million people (nearly twice the ’16 population of Chicago), according to city estimates. That number, if accurate, would make it not only the biggest sports celebration ever, but also one of history’s biggest gatherings of humanity. Cubs fans had to be there. Who knew when such a moment might come again?