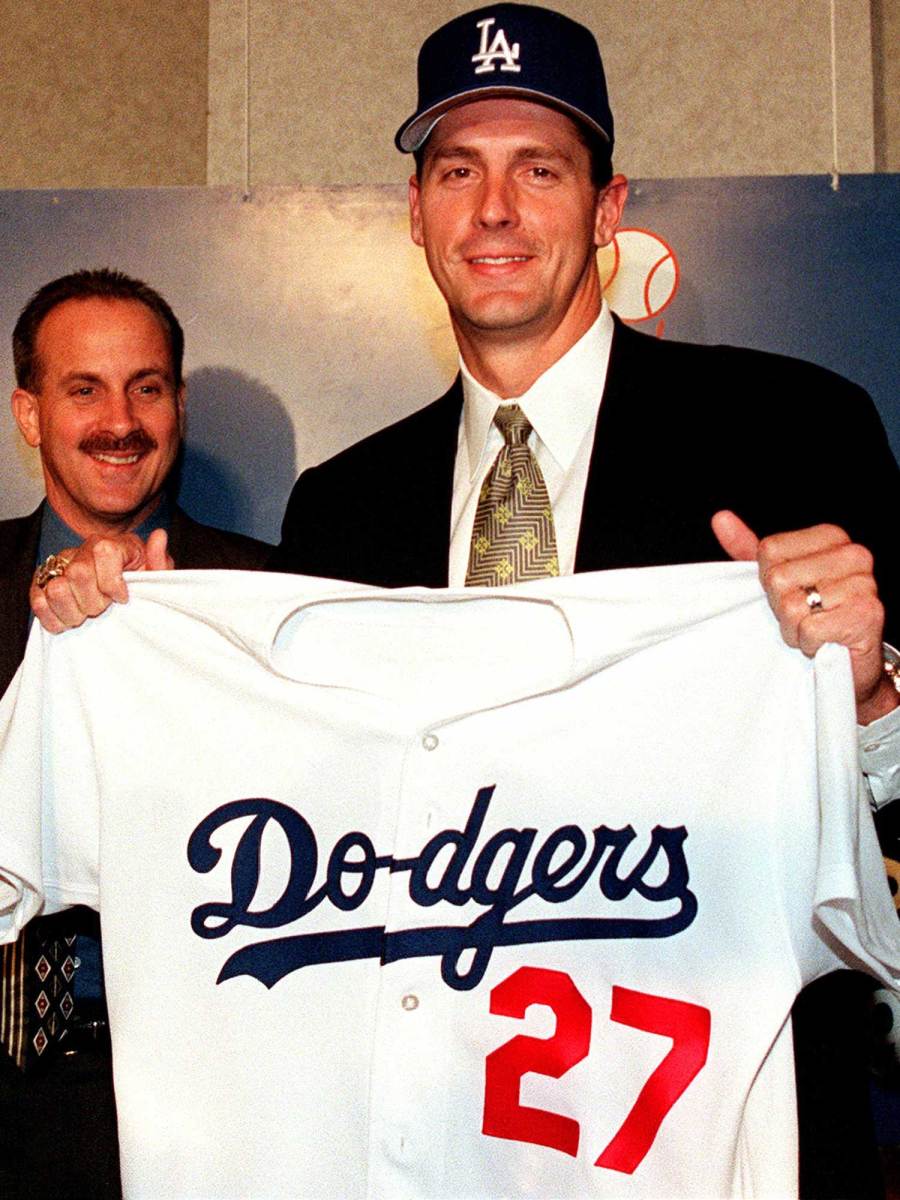

How Kevin Brown Became Baseball's First $100 Million Man

Editor's note: SI is running a series of Bryce Harper stories as he prepares to sign one of the richest contracts in baseball history. Click here to catch up on all of our Bryce Harper Week content.

Twenty years after he declared himself “the new sheriff in town,” ex-Dodgers general manager Kevin Malone wants to emphasize one fact about the contract that permanently changed Major League Baseball: the charter plane trips for Kevin Brown’s family were not his idea.

“Everybody criticized us for granting a charter plane to fly Kevin’s family from Georgia for his starts,” Malone, the first general manager to sign a free agent to a nine-figure contract, states. “The Rockies offered the same thing.”

Whether Colorado offered Brown the luxurious accomodations or super-agent extraordinaire Scott Boras tricked Malone in order to extract more amenties for his client, the Dodgers signed Brown, a 34-year-old starting pitcher, to a seven-year, $105 million contract in December 1998. The deal included 12 roundtrip charter flights from Georgia to Los Angeles so Brown’s family and his young children could watch him pitch, a plush bonus during a chilly era between front offices and free agents.

“Do you think anybody else offered that?” ex-Red Sox and Orioles GM Dan Duquette, Malone's former boss in Montreal turned contemporary in Boston, asks with a laugh.

It was the first contract to break the $100 million ceiling, one that enraged fellow general managers and the commissioner’s office and reminded the public that salaries would only rise as the game grew. As Bryce Harper likely prepares to sign the richest contract in baseball history, the Brown deal recalls a time when front offices bristled at the growth in player salaries, the public sided with teams before players, and tanking wasn’t a strategy that small-market teams employed.

“Nobody was within $20 million of that price tag for Kevin Brown,” says former Reds GM Jim Bowden, now an analyst for The Athletic.

A workhorse righthander who led two pennant-winning pitching staffs (Florida and San Diego) in 1997 and 1998, Brown was revered as one of baseball’s most tenacious and dependable starting pitchers despite his surly exterior. After becoming a full-time starter in 1989 with the Rangers, Brown made at least 25 starts in every season before signing with the Dodgers in 1999 after stops with the Rangers, Orioles, Marlins and Padres. Relying on the power sinker that “you could hear once it left his hand” according to current Yankees pitching coach Larry Rothschild, Brown signed in Los Angeles after the best three-year stretch of his career: two top-five Cy Young finishes, a World Series title and a combined ERA of 2.32 over 727 ⅓ innings pitched. Coupled with incurable competitiveness and ferocious disposition, Brown was considered an occasional pain to play with, but hell to face from 60 feet, six inches.

In his first year as Dodgers GM, Malone had no spending limitations under new owners at FOX. He arrived from Montreal as the young, aggressive executive handpicked by ownership. He was told that his job was to win.

“Mike Piazza had just signed for $91 million in New York and Mo Vaughn signed for $80 million in Anaheim,” Malone says. “I didn’t think it was a stretch to break through this arbitrary $100 million glass ceiling. We wanted his production, his intensity and his ability to make pitchers around him better. We pushed it to the limit because we felt it was worth it.”

Malone’s cocksure demeanor and cutting (and hilarious) press conferences rankled plenty outside of the Dodger organization (and later in his tenure, within it); the Brown contract was the ideal moment for his opponents to pounce. Former A’s and Mets general manager Sandy Alderson, who was working for commissioner Bud Selig’s office at the time, said Malone’s claims that the Dodgers cared about fiscal responsibility and payroll disparity were “an affront and an insult to the commissioner of baseball.” Selig refused to comment on the contract when asked by reporters. Bowden argued that it was dangerous for the competitive balance of baseball.

Malone scoffed at all of it. He still does.

“Sandy Alderson and Jim Bowden didn’t care about competitive balance. They cared about themselves,” Malone says. “I thought they were a bunch of whiners.

“I came from Montreal where we had no money. I worked with a small budget and built the best team in baseball before the strike in 1994 because I knew how to manage a team through scouting and player development. … I didn’t complain when other teams had the best players.”

Brown’s contract was a crescendo for expensive player contracts that emboldened Boras, who secured his reputation as the top superstar agent, while re-adjusting the bullish market for big cities seeking star players. Piazza was the player the Mets used to counteract a dynasty in the Bronx; Vaughn was the Angels’ primary attraction before injuries hindered his tenure with the team; Pedro Martinez became the focal point of the Boston Red Sox after signing a six-year, $75 million contract after he was acquired from the Expos in 1997. Star players headed to major markets while the smaller markets feared they’d be relegated to irrelevance. Malone's strategy was clear: Big shots belong in big markets.

That’s what pushed him to sign Brown. His opponents decried a league-wide wealth gap compounded by American professional sports’ strongest players’ union and the big contract wizardry of Boras.

“I was a GM of a small-market team, so when we saw the Dodgers paid $105 million over a seven-year deal, it was a devastating contract for a market like ours,” Bowden says. “That equaled about four years of our entire payroll at the time.”

TAYLER: A Case for Every Team to Sign Bryce Harper

Was it the number? Was it the fact that that nine-figure seal broke? Was it Kevin Brown?

“I didn’t care about the number,” Bowden says. “I cared that the Dodgers paid over $100 million to a 34-year-old pitcher.”

When you hear Bowden describe the current state of affairs, he celebrates how smart everybody is. While the common fan likes to decry the rise of “analytics,” Bowden enjoys the influx of Ivy Leaguers, Stanford business and Berkeley economics because of how accurately the current generation can assess value. With Harper and Manny Machado entering free agency this year, the public and baseball executives understand that the highest bidders will likely win the services of each player. It’s unlikely that any team or executive will complain about the size of the contract. The 2018 market that allows Harper a contract as high as $350 or $400 million is not the one that paid Brown.

“Today, every team is making money and so player salaries are rising,” Bowden says. “Back then, some teams were losing money and contracts like Brown’s kept us out of negotiations with many free agents.”

Under the most recent collective bargaining agreement, teams have financial windfalls through television deals and a revenue sharing system designed to allow small-market teams to compete for titles. In January 1997, Piazza’s pursuit of arbitration with the Dodgers for an annual salary of $8 million was viewed as greedy by fans even though he was one of the game’s best players. In November 2018, a free agent like Dodgers catcher Yasmani Grandal—nowhere near a player of Piazza’s caliber—can reject a qualifying offer of a $17.9 million annual salary and maintain the trust of the fans; they understand that a desirable salary likely awaits on the open market.

“I view these things much differently now than I did back then,” Bowden says. “The revenue is there. The fans pay for baseball and so the salaries should go up for the best players: they’re the product.”

Commissioner Rob Manfred would cite the Royals’ World Series win and the Astros full rebuild as examples of the current structure’s success. The contrarian would point to the number of tanking teams as evidence that the small-market teams who cried poverty in the prior era are merely hoarding the money granted to them under the new salary structure. When asked if the Yankees would be players for Harper or Machado, Yankees general manager Brian Cashman claimed that he didn’t want to “line the pockets of opponents” by exceeding the league’s luxury tax.

VERDUCCI:Setting the Stage for Bryce Harper's Historic Free Agency

Malone cited Colorado and Baltimore as his two primary competitors during the Brown negotiations. Neither of those franchises considered any top-flight free agents last year, nor will they recruit Harper or Machado to play for them this year. Players are making more than ever, but they are returning to the biggest markets. You won’t find Machado or Harper in Oakland, Tampa or Minnesota. Instead, you’ll see them in pinstripes, in Philadelphia or Los Angeles. The distribution may be different, but the results are increasingly the same.

Malone, long out of baseball and now heading a firm designed to combat child sex trafficking in the United States, chuckles about the deal that angered so many in his industry. “I have a reputation for telling it like it is, I guess,” he says. “I guess this might start some controversy.” His affable tone and sincerity describing his current mission sound like a man humored by the old days of spending and gunslinging, curious about how his decisions affected the way baseball exists in its current form.

“I feel like I was ahead of the curve,” Malone says. “I knew what it took to take care of my team and all I regret is that we didn’t win a championship.”

Brown would pitch two successful seasons in Los Angeles before fatigue started to trouble him. The Dodgers traded him to the Yankees in the 2003 offseason, where he notoriously broke his hand after punching a clubhouse wall. But the question still stands: was anybody else offering those plane rides?

"Scott Boras is as good as they are when it comes to bluffing," Bowden says. "There was never a single team in the $100 million ballpark except the Dodgers."

Nearly two decades removed from baseball, Malone defends his decision.

"If other teams had the resources, they’d have made the deal I made," Malone says. "A bunch of people came up to me after the deal and said 'I would have done the same thing.'"