Drafting High School Pitchers Is a Major Problem for MLB, Health of Young Prospects

White Sox pitcher Michael Kopech threw 90 mph at age 14, 94 mph at 17, 99 mph at 21 and now not at all at age 22. The rookie right-hander blew out his elbow and will miss virtually all of next year while trying to come back from Tommy John surgery.

If you are even a little bit surprised, you haven’t paid attention to what’s happening with high school pitchers over the past decade. They keep throwing harder and harder—and in more competition. And major league teams keep wasting first round picks on 18-year-old kids who throw harder than major league pitchers, which is kind of like hitching a ride with a kid with a learner’s permit behind the wheel of a Formula One racecar and hoping nothing goes wrong. Their still-developing bodies just aren’t equipped to handle the forces of extreme velocity over and over again.

Kopech is just another reason why it’s been a bad year for the best young pitchers in baseball—but not an anomalous one. Let’s start with what’s happened to MLB.com’s pre-season top 11 pitching prospects this year who were signed as teenagers:

2018 MLB.com Top Pitching Prospects, Signed High School Age

A decade or more ago, you could draft a high school pitcher in the first round and reasonably dream you might pluck an ace who stays off the operating table: Zach Greinke, Clayton Kershaw, Cole Hanels, Madison Bumgarner, Rick Porcello, et al.

Now the numbers are so bad when it comes to drafting high school pitchers that after four to seven years, your fireballing No. 1 pick is almost as likely to be out of affiliated baseball as he is to be in your rotation.

From 2011-14 major league teams took 47 high school pitchers in the first round of the draft. Here are the ugly numbers with how those picks have turned out:

• 51% never reached the big leagues (24).

• 40% had elbow or shoulder surgery (19).

• 17% are pitching in the majors with their original team (8).

• 13% are no longer pitching in affiliated baseball (6).

The 2012 high school class is particularly horrific. Of the 15 high school pitchers taken in the first round six years ago, only one is on the active roster of the team that drafted him (Jose Berrios of the Twins). Seven of them underwent Tommy John or labrum surgery (not including Lance McCullers of Houston, who has been shut down with a forearm strain) and five of them are out of baseball—before age 25.

What’s up? Velocity.

The radar gun drives amateur baseball. Cottage industries devoted to velocity have developed now that we know velocity can be improved with skill-specific training—which is why we have adolescents with their growth plates open copying the training regimen of grown men playing Major League Baseball. Training to throw harder is a bit like throwing a curveball as an adolescent: it’s not inherently dangerous, but doing so the wrong way can be ruinous.

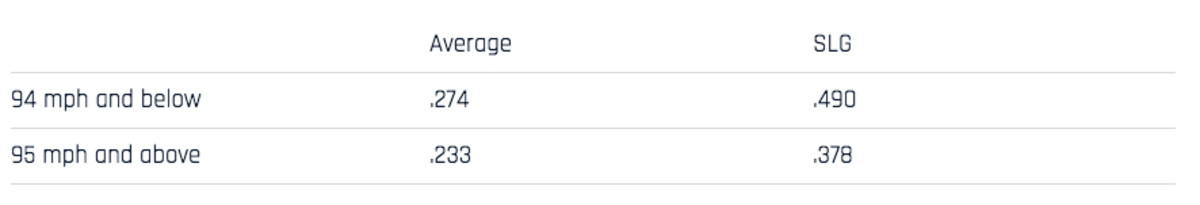

College coaches and major league scouts encourage this emphasis on velocity. It’s what they crave. The emphasis from major league teams has been enhanced by metrics, which have reinforced intuition. Take a look at these numbers and think how you would scout pitchers:

MLB Hitters vs. Four-Seam Fastballs, by Velocity, 2018

The average major league fastball is 93 mph. So when teams scout a high school kid throwing as hard or harder than the average major leaguer, they can’t help themselves when it comes to the draft.

From 2011–18, major league teams took 40 high school pitchers with one of the top 30 picks in the draft. Those 40 pitchers averaged 95.1 mph—38 of the 40 threw 93 and above.

Within the last decade, the effects of Generation Velocity are becoming evident: kids are throwing harder and breaking down more often, but teams keep drafting them early and handing them seven-figure bonuses. Look at the rise in fastball velocity from first-round picks out of high school:

Average Fastball of HS First Round Picks

Of the 78 high school pitchers drafted in the past eight years, 77% of them already were throwing as hard as an average big league pitcher—including 100% in the past two years. Lesson: if you don’t throw 93 mph at 17 or 18, you’re not getting drafted in the first round. So what’s a kid to do? Right: chase velo and max out, health be damned.

The results are predictable. Few aces are coming out of high school in the first round any more. Major league clubs drafted and signed 60 pitchers out of high school from 2008-12. The biggest winner among them is Jake Odorizzi, who has a losing record (47-48) and is on his third team.

What pitchers are dominating this year? Take a look at the leading contenders for the Cy Young Award in each league, and whether they were signed out of high school or college:

NL

Jacob deGrom / College

Max Scherzer / College

Aaron Nola / College

Kyle Freeland / College

Patrick Corbin / College

AL

Blake Snell / High school

Justin Verlander / College

Corey Kluber / College

Chris Sale / College

Gerrit Cole / College

You might point to Blake Snell as a high school success story, and you would be right—as long as you note that when drafted he weighed 185 pounds and threw “only” 90 mph. Now he weighs 200 pounds and is the hardest throwing left-handed starter in baseball—averaging 96 mph and hitting as high as 99 mph. He was allowed to grow into his velocity.

Similarly, only one pitcher from the high school draft class of 2014, which included 10 pitchers, including Kopech, is in the big leagues, healthy, and with the team that drafted him: Jack Flaherty of the Cardinals—who was considered by many scouts to be a top shortstop, not just a pitcher.

As young players become more specialized, a prototype has developed: a pitcher-only high schooler from a warm weather state who throws at least 95 mph. From 2012-14, 78% of first-round high school pitchers were drafted from warm weather states, including 59% from California, Texas and Florida—places where a kid with a great arm can air it out all year round for multiple school and travel teams and showcase events.

MLB Free-Agent Matchmaker: One Player Each AL Team Should Sign

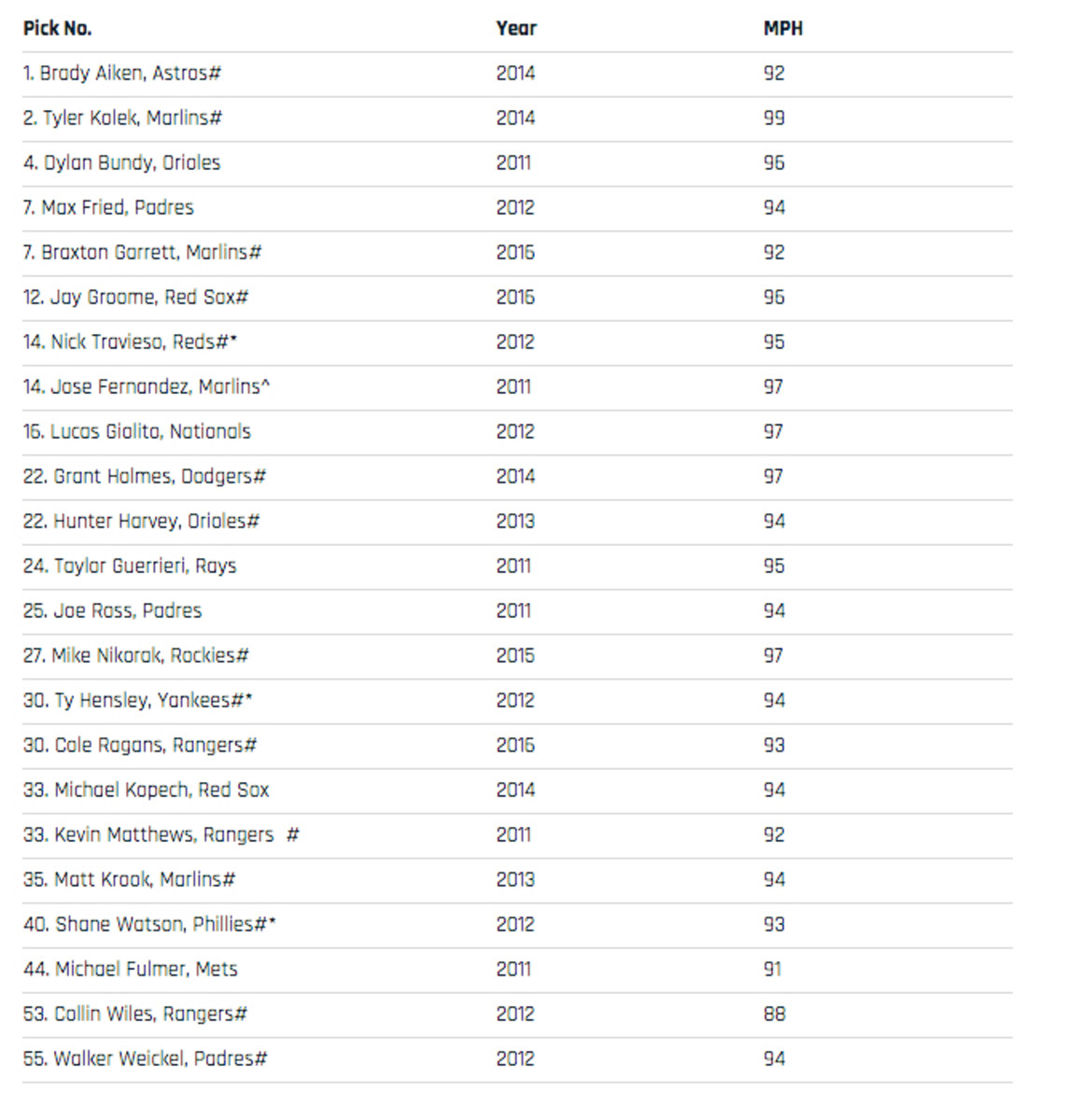

The cost of throwing so hard so often so young is obvious. From 2011–17, 35% of high school first-round pitchers underwent elbow or shoulder surgery (23 of 66). Those pitchers who broke down averaged 94.3 mph in high school. There are only 23 grown men in big league rotations right now who throw that hard.

Here is the casualty list, and how hard they threw in high school (most velocities obtained from Perfect Game showcase events):

Elbow & Shoulder Surgeries, 2011-17 High School First-Round Picks

# Has not reached MLB (15)

* Out of affiliated baseball (3)

^ Deceased (1)

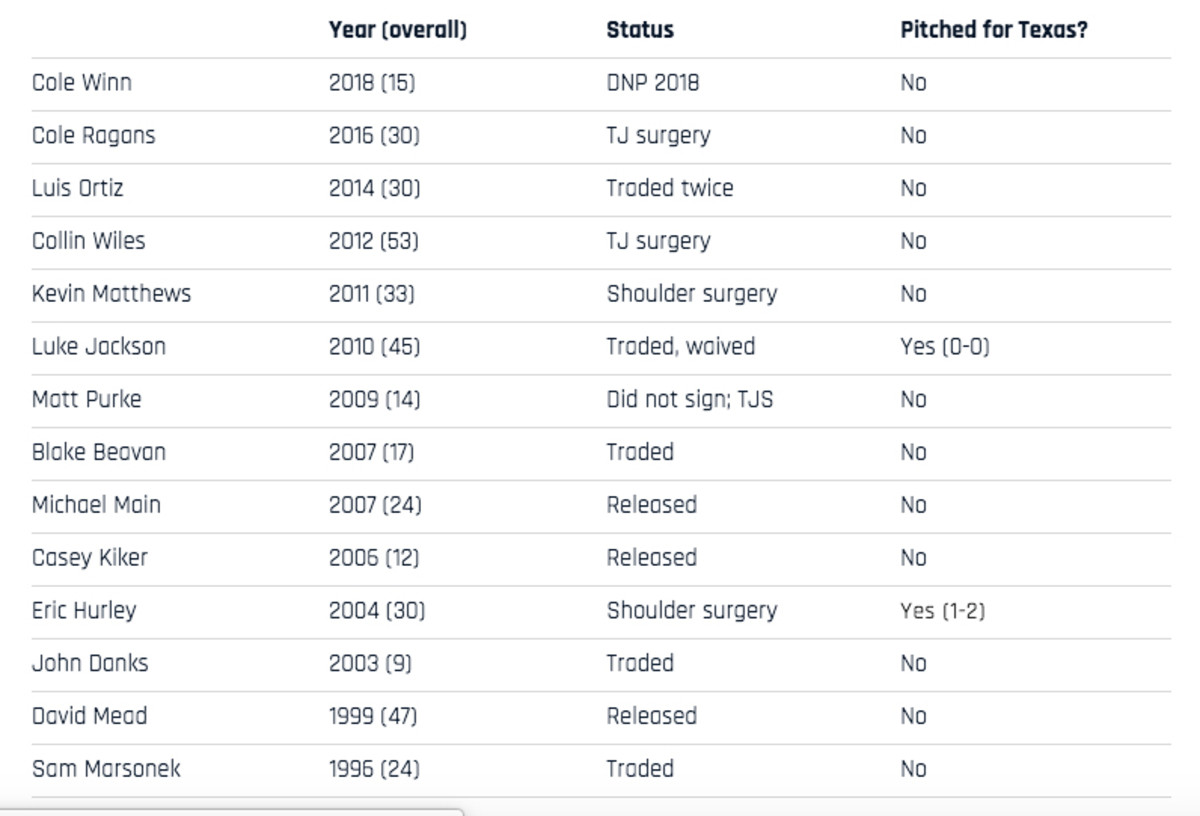

One club that should just stop drafting high school pitchers in the first round is Texas. The Rangers have drafted 14 high school pitchers in the first round in the past 30 years. Those 14 pitchers have won one game combined for the franchise. Not since they took Brian Bohanon in 1987 have the Rangers enjoyed homegrown success from a first-round pitcher out of high school.

Rangers First Round HS Pitchers (1988–2018)

The Rangers are one of three clubs to draft a pitcher with the first overall pick of the draft. None have worked out: David Clyde, Brien Taylor and Brady Aiken.

As young pitchers throw harder and break down more, clubs keep taking them because of the lure of velocity and the misplaced insouciance they bring to Tommy John surgery. Yes, many pitchers can recover in 15 months or so from the surgery. But many do not. And we still don’t know the true fallout from a generation that is getting the surgery at younger ages.

The most ominous story of what can happen when velocity and youthfulness collide is the story of Tyler Kolek. On Aug. 11, 2013, Kolek took the mound in San Diego at the Perfect Game All-American Game. He followed Aiken to the mound. Kolek, out of Shephard, Texas, was 17 years old and 250 pounds. He was clocked at 99 mph, tying Stetson Allie (2009) and Michael Main (2006) for the fastest recorded pitch at a Perfect Game event.

The Marlins loved what they saw—a big kid from Texas throwing 99. They loved Kolek so much they used the second overall pick in the 2014 draft on him. They gave him $6 million.

Kolek reported to rookie ball, where in 22 innings he walked 13 and gave up 17 runs. The next year the Marlins babied him through 25 starts in Class A ball—allowing him just 108 innings. He wasn’t very good there, either (4-10, 4.56).

The next year, 2016, Kolek blew out his elbow in spring training. He underwent Tommy John surgery and missed 15 months. He’s never been right. This year he missed half the season with a bum shoulder, and when he did come back he worked mostly out of the bullpen.

In five seasons since the Marlins burned the No. 2 pick and $6 million on him, Kolek is 5-15 with a 5.34 ERA with nearly as many walks (97) as strikeouts (114). He has never thrown a pitch above A ball.

The three hardest throwers in Perfect Game events have been busts without ever getting to the majors. Allie couldn’t throw strikes and converted to the outfield, but when he couldn’t hit he converted back to pitching. Michael Main, one of the Rangers’ many first-round mistakes on high school pitchers, pitched five seasons—none higher than A ball. The Rangers traded him to the Giants, who released him after one minor league season at age 22.

On that day in August in San Diego in 2013, the major league future must have seemed impossibly bright for not just Kolek, but also the many kids who paraded to the mound at Petco Park throwing as hard as big leaguers. Kolek was one of 11 teenagers that day who threw between 93 and 99 mph. (Only six San Diego Padres have done that at Petco Park this month.) Five of those 11 schoolboy pitchers have undergone shoulder or elbow surgery. The casualties include Keaton McKinney, who underwent two Tommy John surgeries at Arkansas and never played professionally. They also include Michael Kopech.

Alex Cora is easily the best of the rookie managers. He benefited greatly from a year as the bench coach of the Houston Astros. He keeps a terrific balance between challenging his players (he has pushed hard for Xander Bogaerts to raise his game) and winning their confidence. He has been bold enough to admit mistakes (he once admitted he forgot to get J.D. Martinez out of the outfield with a big lead), but has made few of them. Remember, it was Cora who pushed for Boston to dump Hanley Ramirez. Remember him? People were afraid Ramirez would be missed when Boston played the Yankees or would come back to haunt the Red Sox. Cora saw a player whose bat had slowed and had no defensive skills. As in most cases, he’s been proven right.