Trevor Bauer Is More Concerned With Being Right Than Being Liked

This story appears in the Feb. 25, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

Trevor Bauer sits on a folding chair in a drafty warehouse, sipping applesauce from a plastic cup and electrocuting his brain. Well, electrifying his brain, actually. Bauer, who values precision, points out that there’s an important difference. To electrocute something means to injure or kill it. But he will spend 20 minutes with one milliamp coursing, not unpleasantly, between the electrodes affixed near his temples in an effort to improve the organ that was already most responsible for his near Cy Young season with the Indians last year—which, he will tell you, should have been a Cy Young season for real.

The technique is called Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation, or tDCS. Studies have suggested that it can temporarily increase synaptic plasticity, thereby helping subjects acquire skills faster. The U.S. military has used tDCS to expand the capabilities of its target analysts, but Bauer’s mission today is to revamp his changeup. “Anything to expedite the learning curve,” he says.

The warehouse is one of three in an industrial park outside Seattle that houses Driveline Baseball, the think tank-slash-laboratory-slash-training center where Bauer, now 28, has spent most of every offseason since 2013. He is designing this pitch—which will become the final weapon, possibly, in a six-piece arsenal—with the help of machines manufactured by Trackman and Rapsodo (which reveal not only each pitch’s speed but also its movement, spin rate and axis) and a high-speed camera made by Edgertronic, which captures, at 2,000 frames per second, the behavior of each of his fingers as the ball leaves them.

The applesauce is a snack.

While the tDCS device—basically a nine-volt battery with wires attached to it—is new, last winter Bauer deployed the other technologies to develop a slider. The slider worked, and he finally performed as he always told everyone, through six average seasons, that he would. His ERA dropped nearly two full runs, from 4.19 in 2017 to 2.21, the third best in the majors. The point of the slider was to keep hitters from focusing on his curveball, which has always been excellent. The changeup, ideally, will keep hitters from looking for his slider.

Driveline is a testosterone-soaked place—if a woman walked through any of its doors during the two days in January that I spent there, I didn’t see her—and Bauer loves to perpetuate the puerile jokes that clank around like foul balls. He likes to begin his pitch design sessions at 4:20 p.m. He throws three sets of 23 pitches; add them up. He wears T-shirts that read bofa, which ostensibly stands for Bauer Outage For America but is really a reference to male body parts that, unlike the brain, come in sets of two.

Every action undertaken in the warehouses is categorized as either High-T, meaning high testosterone and therefore aggressive and competitive, or Low-T, meaning not. Everyone at Driveline constantly tells Bauer that he falls into the latter category, which seems like trash talk until he reveals that he has asked them to call him that because he is Low-T, physiologically. The normal level of testosterone in the bloodstream for males runs from 250 to 1,100 nanograms per deciliter. Over the past six months, Bauer’s has ranged between 180 and 400, which means, he says, that despite a formidable training regimen and strict diet, he finds it nearly impossible to cut his body fat. To his frustration, the latter increased this winter by 1%, to an unimpressive 22%.

In fact, if you were to line up all of the 50 or so players who were training at Driveline on the days I visited and draft them based on body type alone, Bauer would go nowhere near the top. He is 6' 1", about 200 pounds, and is notably unsinewy.

Still, Bauer was by far the most accomplished baseball player at Driveline, and its alpha dog. He had focused on pitching since watching Tom Glavine, Greg Maddux and John Smoltz star for the Atlanta Braves on TBS as a boy and deciding he wanted to be like them. Back then his father, Warren, didn’t know much about baseball, but he did know about processes—how one thing becomes another. He had been trained as a chemical engineer and worked in the oil fields of California, figuring out how to pull the heavy oil, difficult and expensive to extract, from wells after all the light stuff had been tapped. For Trevor, baseball success would be heavy oil, obtainable only by a process no one had tried yet.

Now, says Bauer’s former Indians teammate Andrew Miller, “he’s shockingly one of the best pitchers in the game, and it’s not because he’s built like Aroldis Chapman or Nolan Ryan. He’s not Nolan Ryan—and yet he throws like him.” Exactly like him in form, if slightly slower in result; Bauer painstakingly modeled his mechanics after the all-time strikeout king’s, and last year his fastball averaged 95 miles per hour and topped out a shade beneath 100.

Bauer’s journey ought to inspire, says Kyle Boddy, the founder of Driveline. “What people should learn about him—what kids should learn about him—is that, f---, it really is possible to pitch in the big leagues, even if you’re just an average, nerdy kid. It requires otherworldly effort, but it can be done.”

For 20 years Bauer has engineered himself for one task only: to throw a baseball. Despite the time of day at which he likes to begin his pitching sessions, he doesn’t smoke anything; he’s never been drunk; his haircut is a number 3, all the way around; he can’t throw a football 10 yards.

Last year, he was running sprints in the outfield when his longtime Cleveland teammate Michael Brantley looked at him with a cocked eyebrow.

“Dude, you are so slow,” Brantley said. “Why are you running sprints? You’re not fooling anyone.”

“Brant, I never claimed to be fast,” Bauer said. “I’m good at two things in this world: throwing baseballs, and pissing people off.”

Bauer is known to Sonya May, her husband, and their four children as Just Trevor. The May family got to know Just Trevor when he was 17 and assigned to stay with them at their home in Cary, N.C., for a week during tryouts for USA Baseball. Sonya could immediately tell he wasn’t like the other teenage prodigies; he was the only one who spent his downtime reading Physics Today and doing card tricks for her kids.

“He reminds me of Sheldon Cooper on The Big Bang Theory,” May says. “He’s the most honest person, and he’s not going to sugarcoat anything. People aren’t used to that.” The Mays were used to it—they are a family of avionics engineers—and a decade later Bauer considers Sonya a second mother and one of his closest friends, a group that isn’t large in part because of his allergy to all things saccharine.

Sheldon Cooper is perhaps the most beloved character on TV, but baseball’s Sheldon is widely seen as a villain, or at least a pest. In conversation Bauer’s effect is unremarkable. He relaxes; he smiles. It’s the content of what he says that is different.

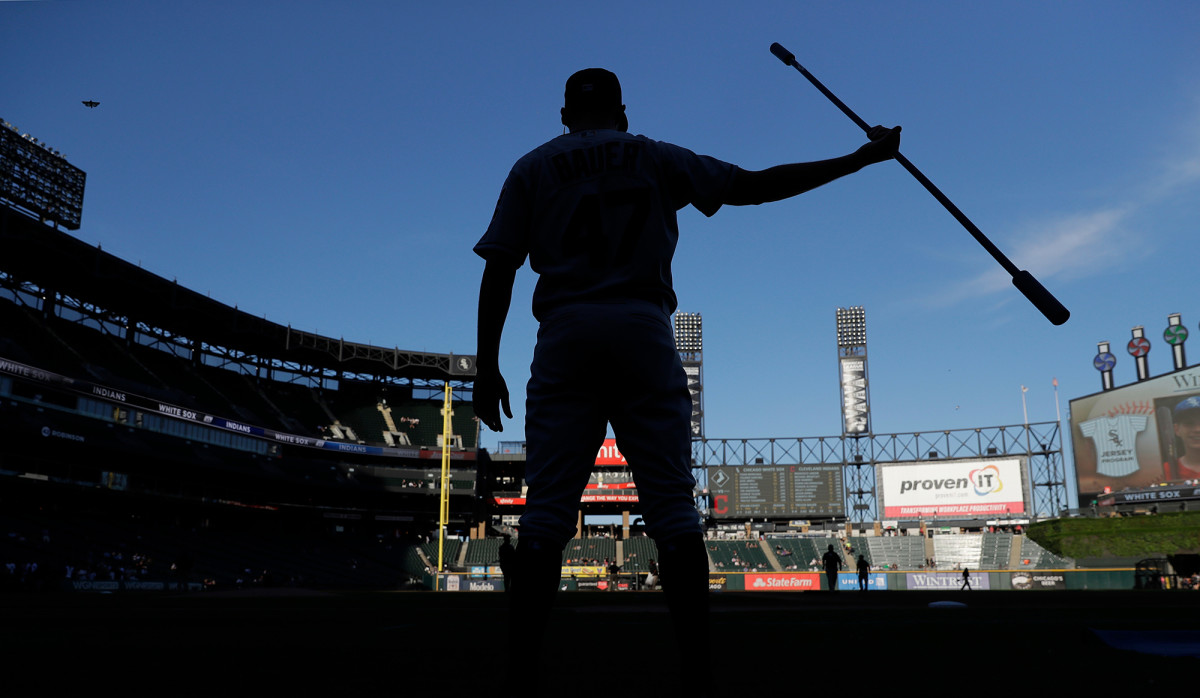

For instance: Bauer says he was certain he was going to win last year’s AL Cy Young until Aug. 11, when a line drive off the bat of the White Sox’ José Abreu fractured his right leg. Even though he trailed the other front-runner, Chris Sale of the Red Sox, by a slim margin in ERA, 2.04 to 2.22, “Sale was going to fade,” Bauer says, “like he always does, and I would have run away with it.” Sale wound up getting hurt, and the Rays’ Blake Snell won the award, but Bauer thinks that if the writers were going to give it to a pitcher with only 1802⁄3 innings—and not Houston workhorse Justin Verlander—then the winner should have been Bauer himself, who threw 1751⁄3. He tied for sixth. Of his own teammate Corey Kluber, who came in third, Bauer tweeted in November: “Plot twist, I was better than Kluber this year.”

“I try to make the things that I say be based in reality, based in facts, and truthful,” Bauer says. “And if that’s the case, and you want to be upset at me for stating the truth, that’s your choice. I don’t know if I’m not afraid of sticking middle fingers in people’s faces, or if I enjoy it. But I end up doing that a lot.”

He’s always been this uncompromising. As a kid in California, all he wanted to do was strike batters out, and those results were the ones he reported to Jim Wagner, his first private pitching coach.

“How’d your weekend go?” Wagner would ask.

“I threw four innings, struck out 11.”

“How many did you walk?”

“It doesn’t matter, Jim. I struck out 11.”

On his recruiting trip to UCLA, he wore a hat bearing the logo of his favorite college basketball team: Duke. The Bruins’ hoops coach, Ben Howland, met the baseball recruits and shook their hands, but pulled his hand away when he saw Bauer. “You’re going to have to take off that hat,” Howland said.

Did he? “No, of course not.”

A current outrage for Bauer is what he is certain is the widespread use among major league pitchers of foreign -substances—particularly a pine tar–rosin blend called Pelican Grip Dip—to make their fastballs spin more and consequently get hit less. Such substances, smuggled to the mound by belt buckle or glove or hair, are banned, but umpires check for them only at a manager’s request. Bauer believes skippers don’t because their own hurlers are sticky-fingered too.

He says, “If I used that s---, I’d be the best pitcher in the big leagues. I’d be unhittable. But I have morals.” He reveals now that he did use Pelican for one inning last year, the first of his April 30 outing against the Rangers, as some statheads had sussed out. He threw nine four-seam fastballs, and they averaged 2,600 revolutions per minute, about 300 RPM higher than normal. Then he stopped, and his spin rate dropped to its standard 2,300 RPM for the remainder of the game. He felt as if he had proved his point.

Bauer has a reputation as a troublesome teammate. Some members of his organization have griped that the clubhouse consists of “24 plus Trevor,” and, says one player, “I think Trevor cares about Trevor a lot.” Of course he does, Bauer says. “In what world is me being a Cy Young winner bad for the team?” he asks. “The better I am, the better the team is, so you should want me to be selfish about how good I am.”

He will drop everything to help out a teammate who asks, he says, but most don’t. “I could’ve fixed Cody Allen’s curveball in two days last year, but I couldn’t tell him anything because he’s a veteran and he doesn’t want to listen,” Bauer says. Allen, the Indians’ former closer, saw his ERA rise from 2.90 to 4.70, and his free agency value plummet.

But less established teammates, like Shane Bieber and Nick Goody and Neil Ramirez and especially Mike Clevinger, are turning to him increasingly often. “He has a rep of having bad character, for some reason—for almost being too honest,” says Clevinger, who, like Bauer, is 28, but unlike Bauer, has shoulder-length hair and gives off a surfer vibe. “It’s not like he’s saying a bunch of lies. The truth hurts, sometimes. His attitude is, if you don’t like me, there’s 7.5 billion people on this planet, so I’m pretty sure there’s others that will, so you can go kick rocks. That bonds us.”

In starts early last season Clevinger’s arm would begin to bother him after a few innings, and his velocity and performance would tumble from there. Frustrated, he asked Bauer what he was doing wrong. “TB sat there and in two seconds said, you’re drifting down the mound, you’re not using your backside properly,” Clevinger said. Thereafter, Bauer would hole up in the Indians’ video room during Clevinger’s starts and call him in, even between innings, to diagnose his mechanical inefficiencies, a practice that Clevinger says upset the Indians’ coaching staff. Clevinger’s breakthrough came in an outing against the White Sox on June 19; he struck out 10, allowed one run, and his fastball averaged 95 miles per hour, two miles faster than his season’s standard. Afterward, Indians manager Terry Francona publicly theorized that the radar gun at Guaranteed Rate Field might have been inaccurate.

“We still die laughing about that, because it was so much work and so much time on Trevor’s behalf and my part,” says Clevinger. “Then Tito’s like, ‘Ah, the gun was hot.’ ”

Bauer considers himself relatively fortunate to be a member of the Indians, which he ranks as one of the more enlightened clubs in the game. Even so, he says, “There is just a massive f---ing gap between No. 1 and the rest.” No. 1, he says, is the Astros, who have heavily invested in Rapsodo and Trackman machines and Edgertronic cameras, and have armed their AL-best staff with data-driven approaches to training and pitch selection—as well as, Bauer contends, with Pelican Grip Dip. Houston also held Bauer’s Indians to just six runs in a three-game ALDS sweep, after which it was not the guru but the pupil who voiced his displeasure to the media. “Kind of had our backs against the wall before this started when it came to the analytical side,” Clevinger said.

Bauer’s impudence and heterodoxy are not confined to baseball, which has led him to enrage a great many people, usually on Twitter. Among other things, he has loudly debated politics and complained about media bias; Bauer ended up not voting in 2016 but identifies as a socially liberal free-market capitalist and thought Donald Trump would shake up the system. He also appeared to question the science of climate change, tweeting, “the climate changed before humans and will change after. For us to think we can control it is extremely ego centric.” He now suggests that he never asserted that humans can’t influence the climate, which was probably too fine a point for 280 characters. The Indians have occasionally suggested to him that he stop using Twitter, and periodically, he has.

Perhaps the team has dwelled more on Bauer’s online activities than he expected it to. After arriving at spring training, he accused MLB’s labor relations department of attempting a “character assassination” against him during his offseason arbitration hearing. He said the opposing lawyers spent 10 minutes of his hearing criticizing his social media activity, particularly the “69 Days of Giving” campaign he conducted last year in which he donated to charities in increments of $420.69 every day for 68 days, followed by a gift of $69,420.69 on the 69th. But their argument didn’t move the arbitrator, who wound up siding with Bauer, awarding him a 2019 salary of $13 million.

The award may have vindicated some of Bauer’s digital irreverence, but other online activities of his haven’t been so charitable. In January he became embroiled in a Twitter battle with Nikki Giles, a Texas State student. It began when Giles jumped into the middle of a light trash-talking session with Astros’ third baseman Alex Bregman to deem Bauer “My new least favorite person in all sports,” and ended dozens of tweets—mostly Bauer’s—later after Bauer had, among other things, scoured Giles’s social media history to find that she had consumed alcohol shortly before she turned 21. Deadspin memorialized the exchange under the headline, TREVOR BAUER HAS BEEN HARASSING A WOMAN FOR MORE THAN A DAY NOW.

At first, Bauer dismisses the exchange as competitive trolling. “It’s a mental chess match, to me,” he says. Eventually, he admits that it runs deeper. “I ignore the vast majority of things people say to me online. Sometimes, I respond. But all you see is the response. You don’t see people wishing that I have my throat sliced open and bleed to death in front of millions of fans on TV, or saying not to come to Detroit because they’re going to kill me and my family for hitting a couple Detroit batters.”

Giles, though, didn’t say anything nearly so nasty. Besides, shouldn’t Bauer, a wealthy celebrity, be above trolling?

“People pull the role model card,” he says. “The way I see it, I am a role model because I show people it’s O.K. to stand up for yourself. That you can stand up to a bully. And I get that a lot of people won’t see it that way. But that’s what it is. When someone goes out of their way to tweet me that I’m a piece of s--- or whatever, that’s a bully.”

Is that really what a bully looks like—an anonymous college student who told USA Today that she spent the next three days crying as Bauer and his followers hounded her?

“It probably isn’t smart,” he finally says. “It probably isn’t ideal. I don’t go out of my way to harass anybody. But, I mean, if you’re going to come at me, that’s just what I do.”

“Most people just hate Trevor,” Boddy says with admiration. “Which he deserves, in many respects.” It seems hard for the ever-logical Bauer to explain behavior that many observers consider irrational. That might be because it’s not entirely rooted in reason to begin with.

On most afternoons, when he was a boy in Santa Clarita, Calif., Bauer would hang a bucket of 48 baseballs from each of the handlebars of his bike and pedal to a local park. His father spent most of the week in New Mexico, running the custom door and furniture company he had opened after he quit working in oil. Warren and Kathy Bauer told their son that they would stretch to pay for his pitching lessons with Wagner and, later, the long-toss guru Alan Jaeger, only if he practiced. So he did, throwing ball after ball against the fence of a tennis court and making sure to eventually return home with each of the 96 balls he had brought with him. He practiced alone; he didn’t have any friends. Bauer recalls kids jeering at him—you’re such a nerd—as he rode by with his buckets.

“Trevor’s an expert in being bullied,” says Warren. “His whole childhood is littered with instances of it, and a lot of his professional career has been punctuated by the same type of impediment.”

There is little that is more difficult than being different in environments, like school and baseball, that are governed by strict norms. Bauer has always been different. He would wear baseball pants to elementary school because he loved the game so much; his classmates would shove him down during recess soccer. His parents told him, “If you want to keep wearing them, that’s going to be the outcome, but it’s your choice.” He kept wearing them.

The training techniques that he developed with his dad and his private coaches—the ones intended to help an average kid become a star—only made him more of an outcast. He used weighted balls and long toss, and threw as often as he could (even in the bullpen during his own starts) against youth baseball’s prevailing wisdom. He began carrying around a six-foot-long, semiflexible, javelin-like tube wherever he went, which he would wiggle over his head and at his side to strengthen his shoulder. His teammates hid the tube in trees. His JV coach told him that he relied on it to compensate for a small penis.

On Friday nights, the students at Hart High would sit together in the student section at football games and then descend upon In-N-Out Burger before going to parties. Bauer was never invited. He sat with his dad, ate with him at Brother’s Burgers, and then went home with him to watch Friday Night Fights.

“For the longest time, I just couldn’t figure out why everyone hated me,” he says. “I used to feel really bad for myself. Like, Why don’t I have any friends? Why don’t girls like me? Why does everyone s--- talk me? Am I really that bad of a person?”

One morning, during his junior year at Hart, Bauer returned home from an early pool workout, took a shower and looked at himself in the mirror, feeling sorry for himself as usual. Then something flipped. “I don’t see anything that I dislike,” he told himself. “I’m going to go off to college and play baseball. I’m successful. I’m smart. I like myself.” From that day forward, he says, “I just stopped giving a f--- what people thought of me. And now I just don’t care.”

He graduated high school half a year early, because he despised it, and enrolled at UCLA as a mechanical engineering major before the 2009 season. The team’s coach, John Savage, had told him he could continue to handle his own development and training as long as it kept working. Another top pitching recruit, a strapping Orange County kid named Gerrit Cole, wasn’t on board. A few weeks into school, as Bauer tells it, Cole reamed him out in front of the whole team in the weight room for not following the same program as everybody else; while they lifted heavy weights, he did his own mobility exercises and wiggled his shoulder tube. “He told me in front of everybody that I had no future in baseball, that I didn’t work hard, and that I’m a p----,” Bauer says. “I was like, ‘F--- you, Gerrit.’ ”

The two essentially didn’t talk for their remaining three years in Westwood—even when they were juniors, when Bauer had a 1.25 ERA and won the Golden Spikes award as the country’s best amateur. They didn’t talk even after Cole was drafted No. 1 overall by the Pirates in 2011 and Bauer went No. 3 to the Diamondbacks. They didn’t talk, in fact, until last year’s UCLA alumni game, when they chatted for 20 minutes about arbitration and Cole’s new team, the Astros. It was, Bauer reports, cordial. Cole said through a rep, “I have a role as a leader on any team I play for, and that is something I take great pride in. There is also a confidentiality with being a great teammate, which I will always uphold. It makes me happy to see fellow Bruins finding success, and they will forever be my teammates.”

Bauer had made clear to any pro team considering selecting him that it would have to let him do things his way—the long toss, the tube—and Jerry Dipoto, the Diamondbacks’ assistant general manager, agreed. But then the Angels hired Dipoto to be their GM four months after the draft and, Bauer says, “My main supporter in the organization was gone. People would s--- on me nonstop.”

He clashed with everyone: the front office, his managers, and the veteran catcher whom he kept shaking off during his first big league starts, Miguel Montero. A year and a half after he’d been drafted and with just four major league outings on his résumé, Bauer had already been shipped off to Cleveland.

The Indians tried to change him too, if more modestly. A few years ago, Bauer says, Mickey Callaway—then the Tribe’s pitching coach, now the Mets’ manager—berated him during batting practice for nearly an hour for refusing to throw more fastballs. Callaway had a point: Bauer’s career ERA was around 4.50. Bauer had a point too. “My process has been the same the entire time,” he says. “I’m going to try to find every single way to do better, and I’ve probably researched it more than you have. Don’t tell me what I do and don’t know without some good f---ing data behind it.”

Chris Antonetti, Cleveland’s team president, says, “He’s helped us advance our thinking on pitching development, and hopefully we’ve had some influence on him as well.”

When Bauer meets a potential romantic partner, he outlines for her the parameters of any possible relationship on their very first date. “I have three rules,” he says. “One: no feelings. As soon as I sense you’re developing feelings, I’m going to cut it off, because I’m not interested in a relationship and I’m emotionally unavailable. Two: no social media posts about me while we’re together, because private life stays private. Three: I sleep with other people. I’m going to continue to sleep with other people. If you’re not O.K. with that, we won’t sleep together, and that’s perfectly fine. We can just be perfectly polite platonic friends.”

It’s his way of being considerate. “I imagine if I was married at this point, I would be a very bad husband,” he says. He does want a family in the future, when he can be as all in on it as he currently is on his career, maybe in a decade or so.

He has a lot to do first. Even though he won’t reach free agency until after the 2020 season, he says, “I won’t be with the Indians next year,” meaning after 2019. He is certain that the cash-strapped franchise will trade him for prospects by next winter. He’s fine with it. It’s logical.

When he does reach free agency, he vows that he will never sign a contract longer than one year. (He has a bet with a friend that will allow the friend to shoot him in the BOFAs with a paintball gun if he does.) He figures he’ll earn a lot more overall—that commitment-shy teams will be happy to give him a series of one-year, $35 million deals—and that he’ll get to play for a contender every year. He figures they’ll want him even more because he’ll start every fourth day. (Only three of Bauer’s 150 career regular-season starts have come on short rest.) And, he says, because of his lifelong training programs and perfect mechanics, he won’t get hurt.

“If that’s what he wants to do, that’s his prerogative, and I’ll do my best to get it done for him,” says his agent, Joel Wolfe. “Just like with so many other things, maybe he knows something that we don’t.”

“My new five-year goal is to be the most internationally recognizable baseball brand,” Bauer says. That is one reason why he continues to engage on social media, despite its pitfalls, and why he gets into so many online tiffs and references the numbers 69 and 420 so much, because his research has suggested that’s what audiences like. While he currently has about 180,000 followers on Twitter and Instagram, he plans for that figure to rise to 10 million in three to five years. He will then leverage that following to expand his fledgling media company—it’s called Momentum; it currently produces short videos of Bauer interviewing friends like Clevinger, Leonys Martin and José Berríos—into a full-service marketing and management conglomerate that, he says, will help solve baseball’s image problem with young people and popularize his antidogmatic approach to pitching. Perhaps it will be improbably lucrative, too.

“I want to be a billionaire,” he says. “Not for any other reason than just to say I did it.”

He’ll have more time to devote to that pursuit because, as a ballplayer, he is nearly a finished product. Just ask him. “There’s optimization to be done, but I’m going to have one of the top 10 changeups in baseball, a top 10 slider in baseball, a top 10 curveball in baseball. I’m going to throw above league average velocity. I’m going to post a mid-two ERA. I’m going to win the Cy Young in 2019. What else do I have to work on?”

Of course, things can go awry. Like a José Abreu liner. Or like the drone blade that famously sliced his pitching hand’s pinkie to the bone on the eve of the ALCS in 2016, splattering his hotel room’s walls with his blood late at night after it unexpectedly began whirring. His stitches opened up just two outs into Game 3 against the Blue Jays, and he didn’t reach the fifth inning in either of his World Series starts against the Cubs, two of the Indians’ four losses.

“Everyone is like, ‘Oh, you’re so stupid for playing with some stupid toy before the biggest game of your life,’ ” he says. “The whole f---ing reason I got into drones was to be better at baseball, because I spent all my time thinking about baseball and I needed something I could do to take my mind off of that. And so, this effort to get better at baseball by developing a new hobby, something that was safe—I’m not drinking, I’m not skiing, or whatever—is what ended up getting me hurt because of a faulty $40 flight board.”

Still, he remains confident in his future plans. He will retire around 2036, after which he will take a year off to travel around the United States by recreational vehicle. Unless, he says, the U.S. is beneath the Pacific Ocean by then, or has been struck by an asteroid, or has otherwise ceased to exist. In which case, he won’t.

Back at Driveline Baseball, among his friends, Bauer has sufficiently charged his brain and his changeup design session has begun. It is unpleasant to watch, but not nearly as unpleasant as it appears to be to perform. “F---,” he grunts, after nearly every substandard offering. “Motherf-----,” he says, sometimes. “Oh, Jesus, what are we doing?” he wails, after one pitch bounces a good five feet in front of the plate. Part of the reason for his troubles is that he insists on randomly mixing in baseballs of different sizes and weights, the theory being that if he can learn to throw his change with them, it’ll speed his mastery of it with just a standard ball.

After one of his 69 deliveries, though, he doesn’t curse but merely nods and continues to do so after he glances at a tablet that displays the Trackman and Rapsodo information about the pitch. When the session ends, he pulls up the high-speed video the Edgertronic camera had captured of his release of that pitch, side-by-side with video of one of his substandard throws, to explain why.

During his non-f--- pitch, he had pulled his middle finger off the ball four frames, or two thousandths of a second, earlier than on the bad one. That reduced the spin rate enough so that it behaved exactly as he hoped it might—like the mirror image of the slider he’d worked so hard last winter to develop. “This is the best changeup in baseball,” he says.

The effectiveness of his slider was further proof, to him, that he had always been on the right path. “These tiny little margins were worth two full runs on my ERA, and however many millions of dollars in surplus value,” he says. “I always believed in my methods wholeheartedly, and that I would have success. Didn’t have any doubt at all. It’s mostly just a nice feeling, like: I did it my way—and f--- you.”

Baseball’s latter-day Sinatra uploads every byte of data he collects from his sessions—all the Rapsodo and Trackman readings, all the Edgertronic video—to Google Drive, where his dad, Warren, reviews it and offers suggestions. Warren considers himself retired, but for the past five years he’s been working from Monday through Thursday as a pitching tutor at ThrowZone Academy, Jim Wagner’s 2,400-square-foot training facility in Santa Clarita.

“We see about 100 players per week, on average,” says Wagner. “Everybody wants to be the next Trevor Bauer.”