Explaining MLB's Monumental Jump in Strikeouts This Year

MLB did something in 2008 that looked fairly unremarkable. The league set a new record for strikeout rate, bumping just a hair above the record of 17.3% after having spent the last decade bouncing back and forth within the boundaries of a single percentage point.

The 17.5% K-rate was not dramatically higher than the previous record from 2001. But it was the start of something big. Baseball broke this record again in 2009—and 2010, and 2011, and every year since, with no signs of stopping. It’s looked like an unrelenting march across the Land of Balls in Play to the Sea of Three True Outcomes.

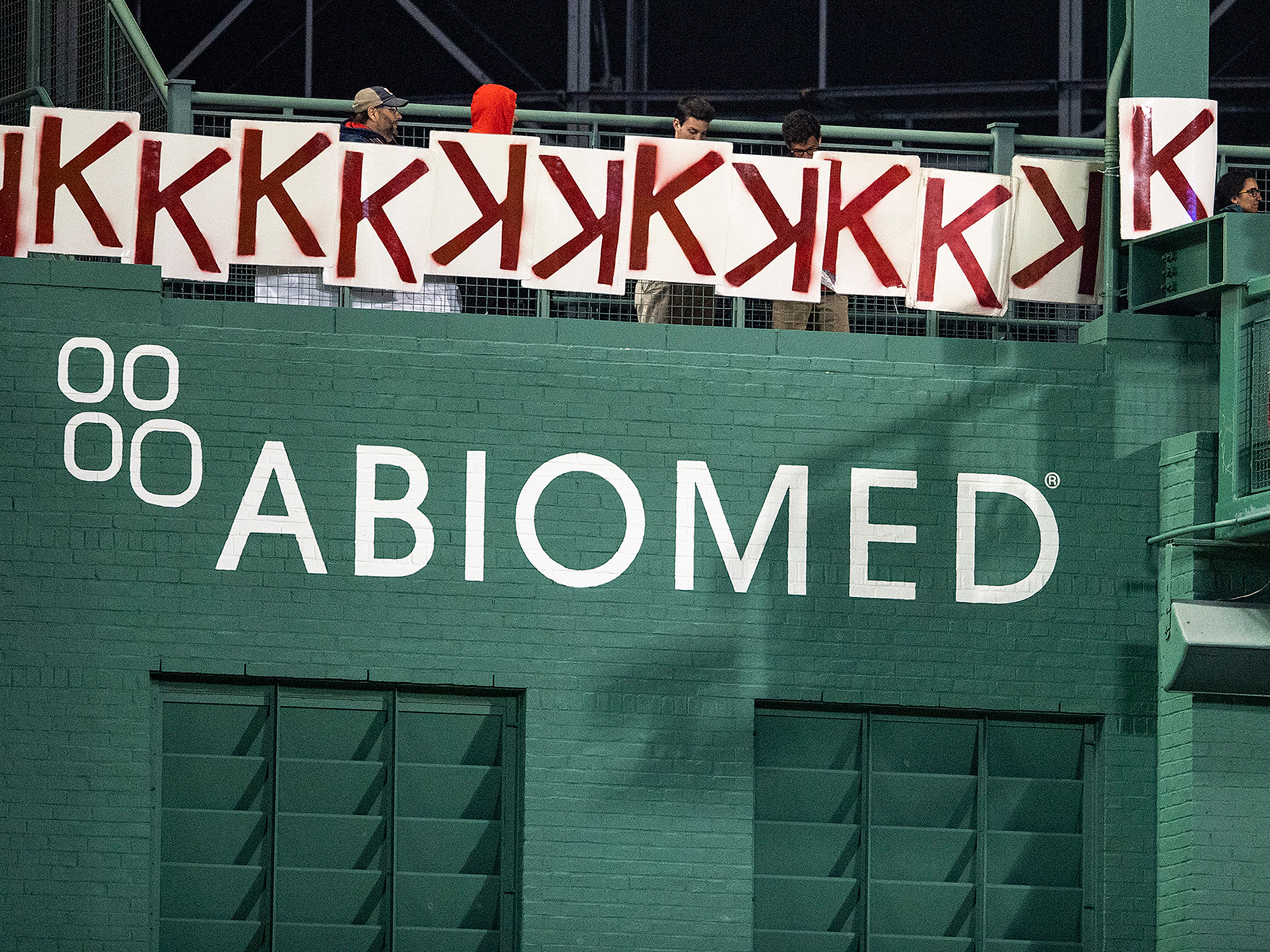

The 2019 season has only offered more of the same. In fact, it’s offered dramatically more of the same. It’s not just that the game’s strikeout rate is on track to set a record for the 11th straight year; at this point, the simple existence of a new record hardly feels worth remarking on. No, it’s that the strikeout rate is on track to set a record by a margin that is nearly a record in its own right. Entering Wednesday, 23.2% of plate appearances have resulted in a K—0.9 percentage points above last season’s rate, which might not sound like very much, but on this scale, a tiny fraction can equal hundreds and hundreds of strikeouts. It’s tied for baseball’s eighth-highest increase, year over year, ever, and it’s the second highest in the last quarter-century. So… what does it mean? What does it look like? And where is it going?

What’s 0.9 Percentage Points, Anyway?

Hey, I get it! An 0.9 percentage point increase sounds tiny—meaningless, even. Is 23.2%so different from 22.3%?

Over the course of a year, it’s a difference of roughly 1,700 strikeouts. It’s less than one for every game. But it’s more than one for every two games. When that’s happening on top of a number that was already a record high, it’s a shift big enough to feel. It’s enough to bring the seasonal total up to nearly 43,000, or roughly one per team per inning. And if it keeps going for another two seasons, it’ll be just about enough for one in every four plate appearances to end in a strikeout.

Of course, it’s not yet there, and it might never get there. Right now, though, it’s a place that baseball has never been before—0.9 percentage points above where it was last year. Sure, it’s a tiny fraction. It’s just one that happens to represent 1,700 K’s.

What’s Behind It?

First, an important caveat: It’s impossible to isolate any single factor here, and even if you could, an increase like this one almost certainly isn’t due to any single factor. It’s likely due to several, working together. We can’t separate variables in a lab to figure out exactly what’s going on here. But we can run down a couple of theories, checking out what the numbers say about the game right now compared to where it was last year:

Pitchers are throwing harder. Nope! This season has actually seen a tiny dip in average velocity. Which makes perfect sense, when you consider the next point…

Pitchers are moving away from the fastball and throwing different stuff. Yep. According to Baseball Savant, fastballs have made up just 58% of pitches this season. (That’s all fastballs: fourseamers, cutters, and sinkers.) This number is down from 60% last year and 62% in 2015. What’s made up the difference? There’ve been a few more curveballs and many more sliders. And those sliders have been harder to hit than ever before. Hitters have a .208 batting average on the pitch in 2019. This isn’t the answer, in and of itself, but it’s probably a small part of it.

There are more pitchers, period. Well, there are definitely more pitchers. There are tons of pitchers. Entering Tuesday—2019’s quarter-way mark—565 pitchers had appeared in a game.Rewind two decades-ish, to 1998, the first season with 30 clubs. There were 557 pitchers who appeared in a game over the course of that entire year. The 2018 season only just set the record here (799 pitchers) and it would not be remotely surprising for 2019 to break 800. So… yes, there are more pitchers. Are those pitchers better, though? That’s a different question.

As you’d expect, these additional pitchers are primarily reliever, as starters’ workloads shrink and teams rely on their bullpens more than ever. As Rob Mains recently illustrated at Baseball Prospectus, however, the growth of and increased dependence on relief corps has coincided with these pitchers performing worse. In other words, there isn’t too much of a statistical gap anymore between the rotation and the ‘pen. It’s harder than ever to draw a line between the two groups. So this point might be a wash: There are more pitchers, which means more pitchers that hitters don’t recognize, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that the net performance level here is higher.

Hitters are swinging more. Not so! In fact, they’re swinging a little bit less (46.1% of pitches, compared to last year’s 46.6%.)

Okay, hitters are chasingmore. This one isn’t true, either. The decrease in total swings has included a dip in swings outside the zone: 30.2%, versus last year’s 30.9%.

So what’s the verdict? Probably a little of everything! There are more pitchers using more varied arsenals, with more hard-to-hit secondary stuff, and who knows what else. There’s a lot going on here. But it’s not simply “hitters worse, pitchers better.”

Has This Happened Before?

Kind of! From 1955 to 1967, the strikeout rate increased enough each season to set a new record for every year. Of course, the scale was different: The 1955 record was 11.4%, less than half of the current rate. (1967 finished at 15.9%.) That’s a big difference, but it wasn’t born of dramatic spikes; in that stretch, there was just one year-over-year increase as high as the one that baseball has seen this season, and in all, the difference between 1955’s and 1967’s K% is not as big as the difference between 2008’s and 2019’s.

Chris Sale's 17Ks tonight...in under 37 seconds. 😳 pic.twitter.com/2F8NvChI2e

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) May 15, 2019

Still, it was a lot. It happened relatively quickly, and it was just one change among a whole set that caused the game to feel the ground shifting beneath its feet. After 1968, baseball lowered the mound and shrunk the strike zone. Pitching became less dominant. Strikeouts went back down.

But this increase in strikeouts isn’t that increase in strikeouts. Really, that increase in strikeouts hardly registered on its own; it was simply a piece of something much larger. MLB’s lowered mound and shrunken zone weren’t a response to the change in the rate of strikeouts. They were a response to an average ERA that had dropped from 4.00 to 2.98. During this increase in strikeouts? The average ERA in 2008 was 4.32. In 2019, it is 4.31.

In other words, this increase in strikeouts is not a sign of a growing fundamental imbalance, a game clearly tilted toward pitching and away from hitting. (After all, it’s been accompanied by similar increases in walks and home runs.) Instead, it’s closer to a sign of aesthetic imbalance. This is much harder to judge, let alone legislate, but it’s clear: Baseball looks different. It just has to decide if it’s comfortable with that.