Bill Buckner Deserves to Be Remembered for More Than One Play

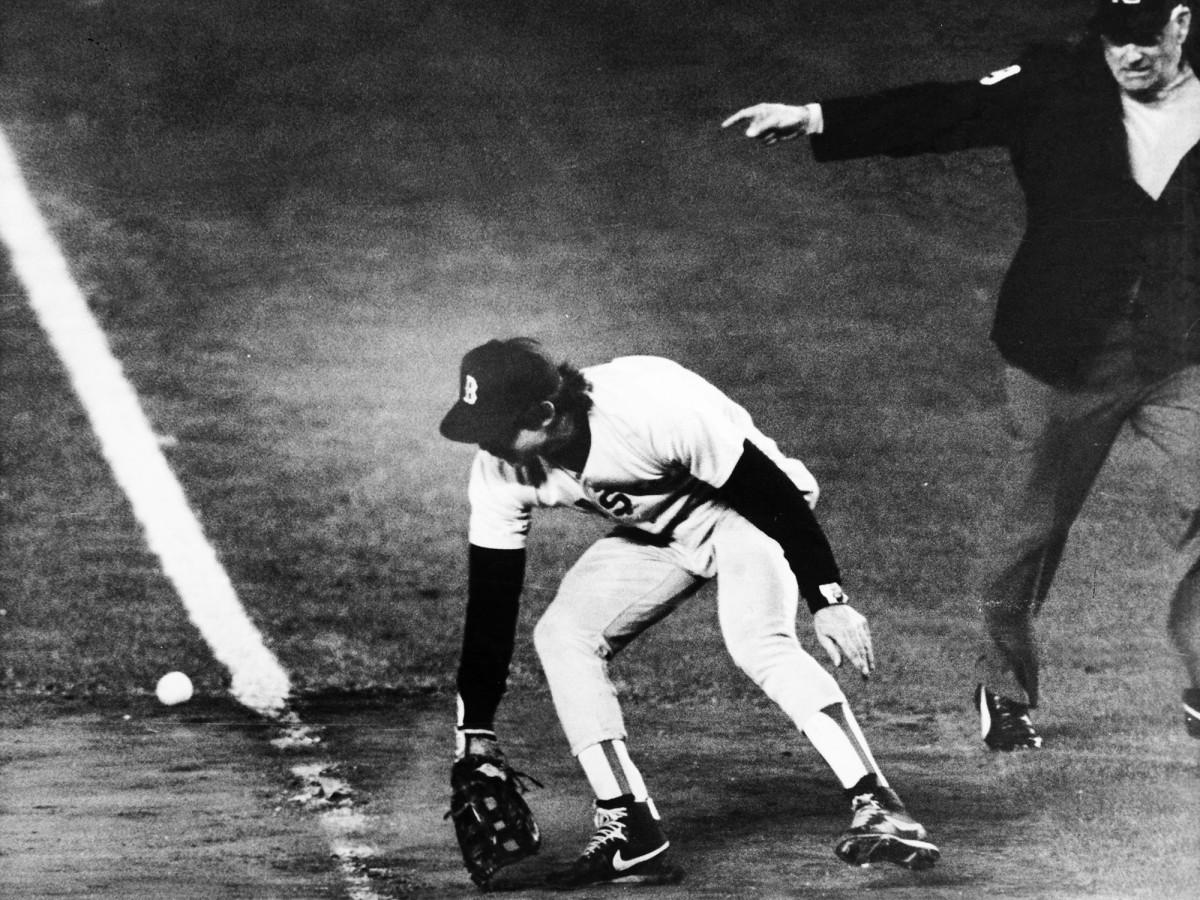

For a generation of Red Sox fans, Bill Buckner’s name was a curse. It was part of the long litany of men who were often invoked in moments of fury and agony—one that stretched as far back as Harry Frazee and included Denny Galehouse, Johnny Pesky, Bucky Dent and Mike Torrez, and that officially added Buckner in the early hours of Oct. 26, 1986, in the 10th inning of Game 6 of the 1986 World Series. The groundball off Mookie Wilson's bat that went through Buckner's legs to finish a Mets rally and Boston’s title dreams neatly encapsulated all the frustrations and foibles of an entire franchise. It also sadly and understandably came to be the enduring image of Buckner.

I was born a few months after the ’86 World Series, and rooting for the Red Sox as a kid, I learned of Buckner primarily as the punch line to a cruel cosmic joke. You only ever saw him as an inevitable part of the interminable montages of October failure that accompanied any of Boston’s postseason games, with Vin Scully providing the excruciating play by play. “Little roller up along first … behind the bag! It gets through Buckner!”

The grounder turned him from player to ghost, forever condemned to haunt bloopers reels and lists of the worst sports mistakes of all-time. That one disastrous moment made Buckner, who died Monday at the age of 69 from Lewy Body Dementia, into a villain: the man who prolonged an agonizing championship drought.

It was also deeply unfair. Buckner’s error was the uppercut that left the Red Sox unconscious on the canvas, but it wasn’t the sole reason they lost. It took a village, as the expression goes: Calvin Schiraldi and Bob Stanley and Rich Gedman and manager John McNamara were as much to blame for Boston’s loss as Buckner. He never should have been out there in the first place: Chronic ankle pain had left Buckner hobbling in the field, and McNamara had been using Dave Stapleton as a defensive replacement for him during the season (as well as in Games 1, 2 and 5 of the series). But he stayed out there in Game 6, because, as McNamara said in 2011, “Buckner was the best first baseman I had.”

But it was Buckner who became the scapegoat as the author of a play that overshadowed two decades in the majors, where all he did was hit. Across 22 seasons stretching from 1969 to ’90, Buckner posted a career .289 batting average and 2,715 hits. He was a contact hitter par excellence and the Platonic ideal of a 1980s ballplayer: He rarely walked or struck out, and his season high in home runs was a mere 18, set in that ’86 season at the age of 36. But from ‘71 through ’86, he averaged 153 hits per year and hit .300 or better seven times. He won the National League batting title with the Cubs in ’80 and was named to the All-Star team—his lone Midsummer Classic selection—the following year.

Boston never even would have reached the World Series in ’86 without his help. In a do-or-die ALCS Game 5 against the Angels, he sparked the game-winning rally with a leadoff single in the top of the ninth.

Game 6 practically erased all of that. “This whole city hates me,” he told his wife Jody after the Series, as Peter Gammons wrote for Sports Illustrated in November 1986. “Is this what I’m going to be remembered for?” And while he was cheered at the post-Series parade in Boston and in his final season in 1990, when he returned to Boston as a free agent and was given a standing ovation in the home opener, he never could escape the cruel taunts and lazy jokes. In 1993, Leigh Montville caught up with him for SI, still living in New England but seemingly desperate to leave. “At least once a week during the season, something is said,” he said. “Why put up with it? I’m tired of it.”

Buckner and his family eventually relocated to Idaho—about as far away as you could go while still keeping a foot in baseball. That’s what he did, spending his post-playing career working as a coach, instructor and manager. His final stop in the game was as the hitting coach for the minor league Boise Hawks before calling it quits in 2014. Over those years, he routinely confronted the error that had come to define his life. He signed autographs of the play with Wilson and starred alongside him in a commercial for MLB Network. He graciously made fun of himself, most memorably in an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm, where he catches a baby falling out of a window of a burning building and is carried off on the shoulders of a crowd.

Twenty-two years after the ball got through him, Buckner returned to Fenway Park to throw out the ceremonial first pitch for the 2008 home opener. The Red Sox were coming off a World Series title—their second in three seasons, after the ’04 victory that brought an end to 86 years of heartbreak and reduced Buckner to a footnote. “Let him know that he’s welcome always,” exhorted Joe Castiglione over the PA, and the sellout crowd did just that, giving him a two-minute-long ovation as he walked from the Green Monster in leftfield to the pitcher’s mound. “I really had to forgive,” Buckner said through tears after the game of his decision to attend; he had previously turned down an invite to join the members of the ’86 team for a 20th anniversary celebration two years earlier. “So I’ve done that. I’m over that.”

The bad decisions and blunders that left the Red Sox high and dry for decades weren’t Buckner’s fault. The so-called Curse of the Bambino was always nonsense—drivel invented to sell books. It swallowed up Buckner the same way it did Torrez and Pesky and countless others, reducing them to their lowest moments while eliminating everything else. He was more than Wilson’s dribbler scooting past his glove, or the bad ankles that slowed him as he chased it. He didn’t deserve to be an epithet or a signpost along a long path of suffering. I know there’s an inherent irony in making that point amid an obituary that focuses on Game 6 and its fallout, but it’s impossible to tell Buckner’s story without that play. It just didn’t have to become his whole story.

Buckner was a fighter. He suffered the ankle injury that would plague him for the rest of his career in 1975 but played through pain for another 15 years. He argued with umpires, brawled with teammates and opponents alike, wrestled with perpetually irascible manager Lee Elia when both were on the Cubs. But over time, he made his peace with the play that made him infamous; he accepted it and lived his life the best he could beyond it. He tried to find a place where he wasn’t Bill Buckner, tragic figure, but simply Bill Buckner, baseball player. That’s all he ever deserved to be.